WARFARE IN ANCIENT GREECE

Paintings of Ancient Macedonian soldiers, arms, and armaments, from the tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki in Greece, 4th century BC

Scarcely any changes seem to have taken place in the character of the offensive and defensive arms of the Greeks from the most ancient period until the Roman time, though the conduct of warfare made enormous advances in the thousand years between the Trojan War and the age of Alexander the Great and his successors. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The Greeks, when they fought from their chariots, dashed at full speed from their own ranks against the foe, and often challenged an enemy to single combat with words of bitter mockery; this was begun with lances, and afterwards, when the combatants had got close together and possibly left their chariots, with the sword; even stones were not despised in the heat of combat. Cavalry was unknown in the time of Homer; the masses of infantry seldom fought hand to hand, but usually from a distance with bows and javelins.

But when they came to close quarters they closed their ranks and locked their shields together; for the principle of the closed phalanx, which became so important for Greek warfare, was indicated even in the heroic age. Their mode of warfare shows the uncivilised condition of the Greeks at that time. Cunning and ambush were regarded as permissible, and cruelty and harshness to the fallen enemy were universal. The captives taken in war became slaves if they were not ransomed, and were sometimes even mercilessly sacrificed. It was considered a glorious deed to rob the fallen enemy of his armour in the midst of the fight, nor was it ignoble to leave his corpse unburied, to be consumed by the wild beasts. Still, there were traces of noble self-sacrifice and comradeship in their conduct towards their own fellow-countrymen.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT GREEK MILITARY factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SOLDIERS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK WEAPONS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK ARMOR: SHIELDS, HELMETS AND 30-KILOGRAM PANOPLY europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT GREEK ARMY: UNITS, ORGANIZATION, SUPPLY LINES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND HIS ARMY: LEADERSHIP, TACTICS, WEAPONS, SUPPLY LINES, FOOD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK NAVY: FIGHTING SHIPS AND SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SPARTAN MILITARY, TRAINING AND SOLDIER CITIZENS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities” by Hans Van Wees (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece”

by Victor Davis Hanson and John Keegan (2009, 1989) Amazon.com;

“Greek Fire, Poison Arrows and Scorpion Bombs” by Adrienne Mayor (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece” by Jennifer Roberts (2017) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age War Chariots” Illustrated (2006) by Nic Fields Amazon.com;

“The Economics of War in Ancient Greece” by Roel Konijnendijk and Manu Dal Borgo | (2024) Amazon.com;

“War and Society in the Greek World” by John Rich (1993) Amazon.com;

“Anabasis” by Xenophon (1847) Amazon.com;

“Alexander to Actium” by Peter Green (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Greek And Macedonian Art Of War” by F. E. Adcock (2015) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece” by Tim Everson (2004) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in the Classical World” by John Warry, illustrated (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Wars of the Ancient Greeks” by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“War and Violence in Ancient Greece” by Hans van Wees Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Michael M. Sage (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Greeks at War” by Louis Rawlings (2007) Amazon.com;

Ancient Siege Warfare: Persians, Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans 546–146 BC” by Duncan B Campbell and Adam Hook (2005) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek Battles

Greek battles were fought on foot at designated sites agreed upon in advance. Before the battle began each side ate a big meal, sacrificed a sheep and drank large quantities of wine. The battles often lasted until one side conceded defeat. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The objective of a battle, when Greek warfare first evolved, was perhaps to starve the enemy out of the valley so that it could be occupied. The victors achieved this by burning the grain fields and tearing up hardier grape vines and olive trees of the looser. This face to face method of fighting evolved, argues historian Victor Hanson, to make battles quick and decisive so that the enemy would not have time to burn their fields and engage in the more time consuming task of tearing up hardy grape vines and olive trees. Armies also did not want to spend so much time fighting that their crops rotted in the fields before they came back.

Before the battle began a no man's land of a 150-yards separated the two armies. With very few preliminaries, the two armies drove forwards at one another like two parking lots of cars headed for a head-on collision. The soldiers poked their spears towards at any piece of flesh they could find — the groin, throats or armpits — and the idea was to breach the shield wall or push the opponents backwards. Panic had a cascading effect. Once the ranks started to break up and soldiers turned around in fear, the soldiers behind them were more likely to panic. This in turn exposed more flesh at which their opponents could aim their spears, and defeat usually proceeded quickly. Most battles lasted no more that an half-an-hour to an hour, with the retreating soldiers often dropping their heavy armor so they could run away.

Many soldiers died during the battle and many more were claimed later by peritonitis (inflammation of a layer around the bone) through spear wounds. Generally the losing army was not pursued and the dead were exchanged under a truce. Greek custom dictated that all soldiers who died in battle were expected to receive a proper burial.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PERSIAN WARS: HERODOTUS, SALAMIS AND ANCIENT GREEK VICTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF MARATHON: DARIUS, PHEIDIPPIDES, FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF THERMOPYLAE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MAJOR EVENTS DURING THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

END OF CLASSICAL GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Warfare in Homeric-Heroic Age of Ancient Greece

Our authorities for the earliest period are but few, but the wars of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. have been carefully described by historians, some of whom themselves possessed military knowledge. We must therefore be content to obtain our knowledge of warfare in early times from the descriptions of poets, who naturally aimed at a very different result from the historian. The Homeric Epics are not authorities which we can follow absolutely in every respect, but still they enable us to form a picture of the warfare of that period, and gain some general notion of the mode in which it was conducted. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The military conditions of that time bore the same patriarchal character which characterised the government of the heroic age. Greece, which even in the historic age was broken up into a number of separate nationalities, was in the heroic period merely a collection of tribes living in constant feud with one another, and undertaking continual predatory expeditions on their neighbours’ territory; the nobles placing themselves at the head of a number of enterprising men, and regarding these proceedings as in no way dishonorable to them.

Sometimes a great common undertaking combined several tribes under one head, but even then the power of this chief was by no means an unlimited one; the separate tribes who took part in the expedition under their own princes and nobles stood under their immediate command, and it depended on the goodwill of these little kings whether they submitted to the ordinances of the chief commander or not. Consequently there could be no question of a common arrangement of the army, or of a subdivision of the people according to the nature of the arms they used; the battle order was drawn up according to tribes.

Nor were they acquainted with any definite plan of battle. The main brunt of the fight was borne by the nobles, who fought from their chariots, and whose single combat with renowned leaders on the other side excited such universal interest that very often the battle stopped Meanwhile. Moreover, these duels were often decisive for the victory or defeat of the whole army.

In the following centuries, after many revolutions and internal contests, the tribes were combined together into separate states, in the manner which continued with slight territorial changes down to the Macedonian period. But as the Greeks never succeeded in becoming one great united power, or even a federation of states, they never attained to a common army, and the armies of Greece were as manifold and various as the circumstances in the various small states of Hellas. Details have come down to us concerning very few; we know most of Sparta and Athens.

Ancient Greek Military Tactics

Unlike their predecessors — the Mesopotamians, Egyptians and Chinese, who maneuvered from a distance with chariots and archers — the ancient Greeks fought ace to face in tightly grouped ranks of soldiers called phalanxes. During the Trojan war chariots were used mainly as transport vehicles. One of the reasons for this was the rugged Greek countryside did not provide enough grazing land to feed a lot of horses, nor did it lend itself to chariot battles which need a lot of flat open space. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

John Porter of the University of Saskatchewan wrote: “In the 7th century B.C. armies came to rely more and more on a formation known as the phalanx — a dense formation of heavily-armored soldiers (known as hoplites) who would advance in close-packed ranks, each soldier holding a round shield on his left arm (designed to protect both him and the soldier to his immediate left) and a long thrusting spear in his right hand.. Unlike the older tactics, which had involved individuals battling on foot or on horseback, this style of fighting relied upon large numbers of well-drilled citizen-soldiers. The defense of the polis came to rest more on the willing participation of its propertied citizens (known, collectively, as the demos or "common people") and less on the whim of its traditional aristocracy.” [Source: John Porter, “Archaic Age and the Rise of the Polis”, University of Saskatchewan. Last modified November 2009 *]

Later, the object was to build a "league of allies." "Subjecting opponents to domination," the Greeks believed, was something that barbarians did. "The 'idea' of military decision," writes historian Jack Keegan, "thus planted itself in the Greek mind beside those other ideas of decision — by majority in politics, of an outcome by inevitability, of a plot in drama, of conclusion by logic in intellectual work — we associate with our Greek heritage." The Greeks invented the notion of the decisive battle. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Armies traveled with sheep which provided food and cloth. The animals were often sacrificed at special points along the way.

Thermopylae

Ancient Greek Fighting Tactics

Warriors carried spears but once they were thrown they were gone, unless a warrior could pick up another one. Rocks were also thrown. "Hoplite warfare" was a common tactic starting around 700 to 600 B.C. A Hoplite was a massed phalanx of armed men in close formation that bullied its way through the enemy line, causing disarray. For this method of warfare to work, each individual had to be in good condition to hold the line..↔ [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Homer wrote in “The Iliad” (c. 750 B.C.): “He spoke and dashed Peisandros from his chariot to the earth, smiting him with his spear upon the breast, and he lay supine upon the ground. But Hippolochos rushed away, and him too he smote to earth and cut off his hands and his neck with the sword, then tossed him like a ball of stone to roll through the throng. Then he left them, and where thickest clashed the battalions, there he set on and with him all the well-greaved Achaians...And the Lord Agamemnon, ever slaying, followed after. [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 17, 56-58]

Soldiers stood shoulder to shoulder, usually eight rows deep, with their shield in their left hand and their spear, projected forward, held with the right hand and tucked between the elbow and ribs. The entire phalanx tended to move to the right as each man tried to get close to the protection of his neighbor's shield. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Greek hoplites were not successful because they were skilled swordsmen or brave but because they kept their ranks and attacked in unison. At the Battle of Cunaxa, in 401 B.C., it was reported, the Greeks slaughtered the Persians without suffering a single fatality.

Alexander the Great’s Military Tactics

Alexander liked to strike quickly. Some credit him with perfecting the cavalry charge. He often ignored the advise of his generals who advised caution and seemed little worried if his enemies held the high ground or some other advantageous military position.

At the heart of Alexander’s army were rows of disciplined soldiers with pikes, spears and swords that were organized into a “phalaiazn” and were capable of overpowering far larger enemy groups. The front rows were armed with sarissaes which had a longer reach than their opponents. Rear troops pushed forward and helped the front-row troops press ahead. Archers, slingers and cavalry attacked and defended the sides.

Foot soldiers in Alexander the Great's army learned to withstand chariot advances by aiming their weapons at the horses first: by employing arrow-proof armor and shields; and by organizing themselves into tight chariot-proof ranks.

Alexander conducted at least 20 sieges, but none within Persia because the empire was supposedly guarded from its perimeter. The three main battles — Granicus, Issua and Guagamale — were fought in open country.

Alexander relied heavily on spies. He also purportedly spied on his own soldiers by intercepting their outgoing mail. According to legend, Alexander was the first commander to require that all of his soldiers be cleanly shaven. This was so that enemies could have nothing to hold on to. ◂

Civilians were often targeted, especially in Lebanon and the Indus Valley, where large number of innocent people were killed for no military reason. The historian Ernst Badian told National Geographic, "Blood was the characteristic of Alexander's whole campaign. There is nothing comparable in ancient history except Caesar in Gaul."

See Separate Articles:

ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND HIS ARMY: LEADERSHIP, TACTICS, WEAPONS, SUPPLY LINES, FOOD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT BEGINS HIS CAMPAIGN AND BATTLES THE PERSIANS AT GRANICUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT BATTLES THE PERSIANS AT ISSUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT DEFEATS THE PERSIANS AT GAUGAMELA europe.factsanddetails.com

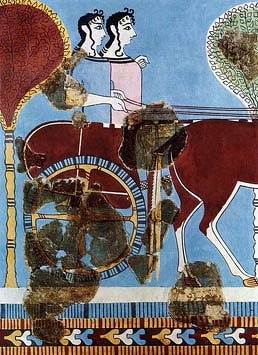

Chariot Fighting in Ancient Greece

The nobles appeared in full armour, accompanied by their charioteers, on their war chariots, usually drawn by two horses. On one vase painting the painter has represented four horses drawing the chariot, but in so doing he was not following an old tradition, since in his time the custom of fighting with chariots had long ceased, but rather the universal practice of ancient vase painting, which always represented war chariots with four horses, following the example of the Quadrigae used in races. The warrior stands holding the reins in his left hand, and his spear in the right, and has not yet mounted his chariot; he is in full armour, and so is the warrior standing in front of the chariot, and consequently we are justified in supposing that this really represents a war chariot. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Factinator posted on Quora.com in 2023: The Mycenaean Greeks used chariots in battle. Administrative records in Linear B script , mainly in Knossos, list chariots (wokha) and their spare parts and equipment, and distinguish between assembled and unassembled chariots. The Linear B ideogram for a chariot (B240, D800;DCCC;) is an abstract drawing, showing two four-spoked wheels. The chariots fell out of use with the end of the Mycenaean civilization, and even in the Iliad, the heroes use the chariots merely as a means of transport, and dismount before engaging the enemy. Chariots as I mentioned already were retained only for races in the public games, or for processions, without undergoing any alteration apparently, their form continuing to correspond with the description of Homer, though it was lighter in build, having to carry only the charioteer. Now on to classical Greece the classical Greeks had a (still not very effective) cavalry, and the rocky terrain of the Greek mainland was unsuited for wheeled vehicles which is a reason why warchariots and cavalry in ancient Greece we so rarely used or we smaller than most cavarlies in history.

Ancient Greek Defenses

Many ancient Greek city states were walled. Fortification walls served several purposes, including protection from invasion and as markers of territory. Walls were first constructed around the city's Acropolis, to ensure the safety of the most important part of Greek society — their sacred space. The extent to which the defensive walls protected only the city-center, or spread into the countryside, varied. The intensity of defense measures depended on a city's vulnerability and likelihood of attack. [Source Wikipedia]

Few Classical Greek cities were located right on the water because of worries about piracy and hostile raids. The Greeks tended to fortify places at a safe distance from the sea, and habitation tended to cluster around the citadels. Athens, for instance, was six kilometers inland from its port, Piraeus; Corinth was similarly distant from its two harbors; and Sparta, the least maritime of all major Greek cities, was 30 kilometers from its port. [Source Encyclopedia.com]

It was common for Greek establishments to be set up at naturally defensible locations such as mountains and rivers. These natural barriers sometimes prevented the need to build fortifications. Choosing geography as a means of defense only increased with the development of colonies. When specifically looking to where to build a new city, rulers chose locations with defense in mind. An example of this can be seen at Mount Oneion, Corinthia. Located on the Corinthian isthmus, the Mount Oreion mountain range provided a natural barrier for the city. In low sloping planes, such as the sites of Stanotopi and Maritsa, walls were constructed to add to protection.

Towers provided a variety of purposes for the Greeks. They were a place to store military supplies and provide lookouts out over the fortification walls. In the Hellenistic Period, there was a shift in the construction and placement of towers. This is due to the increasing necessity to have what would be the strongest defensive line. Prior to the Hellenistic Period, towers were largely simple, single-storied square buildings. Due to advances in military technology this style of tower changed. At the start of the Hellenistic Period, towers were incorporated into the fortification walls. Later, there was a shift to towers being constructed separate from the wall system. Circular or multi-angled towers would have been more difficult to incorporate into the flat-walled architecture. They were also separated due to their vulnerability to attack.

Under the guidance of the tyrant of Dionysuis I, engineers in Syracuse developed the catapult. "The catapult had an effective distance of up to 50 meters," a German archaeologist told National Geographic, "It could hurl not only stones but also arrows. No longer did people have to fight person-to-person. Catapults were moved across field on top of towers ten meters high. That was tall enough to attack an enemy inside his own walls."

Dionysius is also credited with using 60,000 men and 6,000 oxen to build a wall around Syracuse to protect it from a Cathaginian attack. The 20-foot-thick wall still stands on the northern edge of Syracuse.

Ancient Greek Sieges

The battle of Troy was basically a siege but a lot of the fighting took place outside the walls. You don't read so much about sieges until the time of Alexander the Great. Schliemann’s excavations at Mycenae and Tiryns have proved to us the magnificence of some ancient fortifications. It is, therefore, natural that the siege of a strongly-fortified place was a difficult matter for a Greek army, since effective besieging machines were only very gradually invented. For centuries they contented themselves with simply surrounding a city and trying to force it by hunger; an even more favorite device was trickery or treachery; they were neither able to storm a town nor make breaches in the wall. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The first machine for storming made use of by the Greeks was the ram, an invention of the Carthaginians, but this, too, was ineffectual against very strong walls. They, therefore, very often resorted to the device of undermining the walls in order to make them fall; sometimes they raised the ground for attack by constructing a mound, or made movable towers in order to enable them to fight from the same height as the garrison. There were various devices, too, for setting the town, or at any rate its fortifications, on fire; and if the local conditions permitted it, they sometimes tried to reduce the besieged to extremities by cutting off their drinking water, or producing an artificial flood.

This primitive kind of siege warfare only gave way to a more rational method during the Macedonian wars; it was in particular the merit of King Philip, instead of enclosing a city, to concentrate the attack on one point in the wall, in which breaches were made. The discovery of heavy artillery, the perfection of breaching implements, movable batteries, protective apparatus, and revolving turrets, did not take place till the Alexandrine age.

Adrienne Mayor wrote in National Geographic: Raining fire down on attacking forces was a common defense by those under siege. Around 360 B.C., Aeneas Tacticus (the first Greek author to write on the art of war) composed On the Defense of Fortified Positions, in which he devoted a section to this strategy. The text recommends a gruesome three-step defense. First, those under siege should pour pitch down onto the enemy soldiers and their siege engines. Next, they should hurl bundles of tow and lumps of sulfur, which get stuck in the pitch. The third step would be to lob burning wood chips toward this sticky target. As the easily kindled tow ignites, the sulphur burns, releasing sulphur dioxide and sulphuric acid. Tacticus also describes a wooden bomb covered with iron spikes and filled with explosive material that could be dropped onto the enemy’s siege engines. The spikes would hold the flaming bomb in place on the target. He explains that “fire which is to be powerful and quite inextinguishable is to be prepared as follows. Pitch, sulphur, tow, granulated frankincense, and pine sawdust in sacks you should ignite and bring up if you wish to set any of the enemy’s works on fire.” [Source: Adrienne Mayor, National Geographic History, May 25, 2023]

See Separate Article:

SIEGE OF TYRE AND ALEXANDER THE GREAT IN PHOENICIA factsanddetails.com

Poisoning the Wells of Kirrha

Adrienne Mayor wrote in National Geographic History: The earliest documented case of poisoning water occurred during the First Sacred War in Greece, about 590 B.C. The Athenians and their allies contaminated the water supply of the besieged city of Kirrha, using hellebore, a toxic plant that grows in abundance all around the Mediterranean. Notably, historical sources attribute the plot to four different men, one of them a doctor. This act demonstrates the collateral damage biological warfare inflicts. It harms not only soldiers but also noncombatants: The elderly, women, and children inside the walls of Kirrha were all killed. After the First Sacred War, the Athenians and their allies agreed never to poison the water of fellow members of their alliance. [Source: Adrienne Mayor, National Geographic History, May 25, 2023]

Hellebore blossoms are beautiful to look at, but the plant is deadly. The ancients were familiar with black hellebore and white hellebore. Although unrelated, both variants are poisonous. In ancient sources, “hellebore” can refer to plants from two unrelated genera: “Helleborus” and “Veratrum”. Black hellebore in this illustration gets its name from the color of its roots and is a member of the buttercup family, while white hellebore belongs to the lily family. In large doses they can cause severe vomiting and diarrhea, muscle spasms, delirium, and even cardiac arrest.

In the sixth century B.C., hellebore was the toxin of choice for the Amphictyonic League when it laid siege to the city of Kirrha during what has become known as the First Sacred War. The conflict was sparked when inhabitants of Kirrha began seizing land from the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, shown here in an 1894 watercolor by Albert Tournaire, as well as ambushing pilgrims passing through on their way to the sanctuary. Kirrha enjoyed a strategic location on the route between the Corinthian Delta and Delphi. The Amphictyonic League, which had been set up to protect the sanctuary, retaliated by poisoning the city’s water supply. When the Kirrhans drank, “the men defending the walls had to abandon their positions out of never-ending diarrhea,” leaving the city defenseless as it fell around 590 B.C.

Different versions of events place the blame on different people. Frontinus, a first-century Roman civil engineer, claimed that Cleisthenes of Sicyon masterminded the siege and putting toxins in the water by cutting the pipes and reconnecting them after poisoning the supply. According to the geographer Pausanias, the great Athenian statesman Solon, shown in an ancient bust, was responsible for the plan: first diverting the Pleistos River to leave Kirrha without a water supply and then, having poisoned the water, restoring the river’s course.

Tunnel Warfare in Antiquity

Tunnel warfare has been used since the 9th century B.C. Elias Chavez wrote in Business Insider: The first known use of the tactic dates back to the Ancient Romans and Persians, who would tunnel under barricades and walls to enter city walls and fortresses.[Source: Elias Chavez, Business Insider, November 4, 2023]

Originally called "mines" instead of tunnels, ancient Assyrians in the 9th century B.C. would get as close to a city wall as possible and try to undermine its foundations. Because digging took so long and exposed them to fire from above, ancient civilizations realized that the safest approach was to start a tunnel further away and dig toward city walls.

Israelites built a vast network of 450 tunnels — some of which were used against the Roman Empire. The tunnels in Israel date back to the first century B.C. and were used for myriad purposes. Jewish rebels used tunnels to revolt against and hide from the Roman Empire. The network of tunnels is expansive, with some tunnels leading to trap doors in villages or large columbariums. The tunnels provided escape routes and shelter from the Roman Empire during the Bar Kokhba revolt. However, the Roman Empire overwhelmed the Jewish rebels and won the war, eventually tearing up the streets, finding the tunnels, and taking their village.

In addition to destroying the foundations of defensive walls, ancient Greeks and Romans utilized early chemical warfare in tandem with tunnel warfare to infiltrate cities. During a battle in 189 B.C., ancient Greeks burned chicken feathers to smoke out Roman invaders.

The advent of tunneling brought on the use of countermines, defensive tunnels built inside a city wall constructed to locate or trap tunneling from the outside. When Persians dug tunnels underneath the walls of Dura-Europos, a Roman-held Syrian city, the Romans began digging counter tunnels to stop the invasion. But the Persians were aware of their enemy's strategy. As the Romans began to emerge from the tunnels, the Persians blew poisonous smoke made from burning sulfur and bitumen at them, which turned into sulfuric acid in their lungs. "It would have almost been literally the fumes of hell coming out of the Roman tunnel," Simon James, an archaeologist and historian from the University of Leicester, told LiveScience.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024