Home | Category: Alexander the Great / Alexander the Great's Conquests / Military

ALEXANDER THE GREAT AS A LEADER

Alexander the Great (356 to 324 B.C.) was a superb military commander. Believing himself invincible and specially blessed by the gods, he often led the cavalry charges himself, which often proved decisive, and often wore an easy-to-spot white-plumed helmet. He suffered severe sword, lance, arrow and knife wounds. Alexander once told his men, "There is no part of my body...which has not a scar...and for all your sakes, for your glory and your gain." [Sources: Richard Covington, Smithsonian magazine, November 2004; Caroline Alexander, National Geographic, March 2000; Helen and Frank Schreider, National Geographic, January 1968. [↔]

“As a warrior and a strategist, no one compares with Alexander,"Alexander biographer Lane Fox told Smithsonian magazine, “He would have made mincemeat of any Roman who came over the hill. Julius Caesar would've gone straight back home as fast as his horse could carry him." And Napoleon--- “Alexander would've wiped him out too. Napoleon only fought dodos."

Alexander had full confidence that his men would follow him. Admiral Ray Smith, a former Navy SEAL told National Geographic, "We have learned that the key to leadership under the toughest possible circumstances is that officers and men undergo the same training. Men know their officer is not asking them to do anything he couldn't do or hasn't done."

Arrian wrote: “In marshalling, arming, and ruling an army, he was exceedingly skilful; and very renowned for rousing the courage of his soldiers, filling them with hopes of success, and dispelling their fear in the midst of danger by his own freedom from fear. Therefore even what he had to do in secret he did with the greatest boldness. He was also very clever in getting the start of his enemies, and snatching from them their advantages by secretly forestalling them, before any one even feared what was about to happen. He was likewise very steadfast in keeping the agreements and settlements which he made, as well as very secure from being entrapped by deceivers. Finally, he was very sparing in the expenditure of money for the gratification of his own pleasures; but he was exceedingly bountiful in spending it for the benefit of his associates.

Alexander also showed great compassion for his men. "For the wounded he showed deep concern," wrote Arrian. "He visited them all and examined their wounds, asking each man how and in what circumstances his wound was received, and allowed him to tell his story and exaggerate as much as he pleased."

Macedonian cosplayers

Alexander the Great Timeline:

356 B.C.: Born at Pella, Macedonia, to King Philip II and Olympias

336 B.C.: Acceded to throne of Macedon

336 B.C.: In same year, is recognised as leader of Greek-Macedonian expedition against Persia

334 B.C.: Wins Battle of the Granicus River

333 B.C.: Wins Battle of Issus

332 B.C.: Accomplishes siege of Tyre

331 B.C.: Wins Battle of Gaugamela

328 B.C.: Manslaughter of 'Black' Cleitus at Samarkand

326 B.C.: Wins Battle of river Hydaspes

326 B.C.: In same year, troops mutiny at river Hyphasis

324 B.C.: Troops mutiny at Opis

323 B.C.: Dies at Babylon

[Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ALEXANDER THE GREAT (356 TO 324 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S MARCH OF CONQUEST europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S APPEARANCE, CHARACTER, PERSONALITY AND HABITS factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S EARLY LIFE factsanddetails.com ;

PHILIP II (ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S FATHER) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S PERSONAL LIFE: WIVES, FRIENDS, LOVERS, CHILDREN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER BECOMES KING OF MACEDONIA AND THE ELIMINATION OF RIVALS AND THREATS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PLOTS, SUSPICIONS, INTRIGUES, MURDERS, EXECUTIONS AND ALEXANDER THE GREAT factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK MILITARY factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SOLDIERS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK WEAPONS AND ARMOR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK ARMY: UNITS, ORGANIZATION, SUPPLY LINES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WARFARE IN ANCIENT GREECE: BATTLES. TACTICS, METHODS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SPARTAN MILITARY, TRAINING AND SOLDIER CITIZENS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites: Alexander the Great: An annotated list of primary sources. Livius web.archive.org ; Alexander the Great by Kireet Joshi kireetjoshiarchives.com ;Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Generalship of Alexander the Great” by J. F. C. Fuller (1958) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army” by Donald W. Engels (1978) Amazon.com;

“The Army of Alexander the Great” by Stephen English (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Army of Alexander the Great” (Men at Arms Series), Illustrated, by Nicholas Sekunda (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Army of Alexander the Great” by Richard Taylor (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Macedonian War Machine, 359–281 BC: Neglected Aspects of the Armies of Philip, Alexander and the Successors (359-281 BC)” by David Karunanithy (2020) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great An Illustrated Military History” more than 250 pictures, by Nigel Rodgers (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Macedonian Army of Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359–323 BC: History, Organization and Equipment” by Gabriele Esposito (2023) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great at War: His Army — His Battles — His Enemies” by Ruth Sheppard (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Genius of Alexander the Great” by N. G. L. Hammond (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Field Campaigns of Alexander the Great” by Stephen English Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Philip Freeman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Alexander of Macedon” by Peter Green (1974) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Robin Lane Fox (1973) Amazon.com;

“Alexander the Great” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

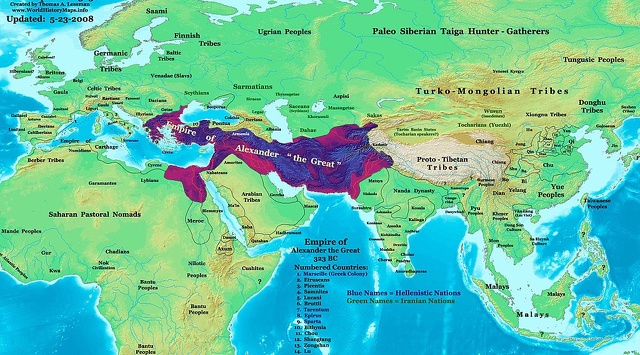

Alexander the Great’s March of Conquest

Alexander the Great (356 to 324 B.C.) left Macedonia in 334 B.C. at age of 21 with 43,000 foot soldiers and 6,000 horsemen. He would never return home again. After crossing the Hellesport (now known as the Dardanelles), he marched into Asia Minor and then looped around Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Egypt, and Libya before returning to Asia Minor (this took about four years). Then he and his army zigzagged through Iran and Iraq, where important battles were fought (three years), and continued on through the Hindu Kush mountains in Afghanistan and into Pakistan (three years). [Sources: Richard Covington, Smithsonian magazine, November 2004; Caroline Alexander, National Geographic, March 2000; Helen and Frank Schreider, National Geographic, January 1968. [↔]

Alexander went as far north as present-day Tashkent in Uzbekistan and as far east as Jammu and Armistar in India. He followed the Indus River in present-day Pakistan to the Arabian Sea (two years). The most difficult and costly part of the journey was the trip home via the forbidding Baluchistan desert in southern Pakistan and Iran (one year).

Why did Alexander undertake his mission of conquest and how did Alexander get his men to go along with him on arduous journey of conquest that had little point. Some say the conquest seems to have been a personal matter for Alexander without further meaning. According to historian Jack Keegan, Alexander was comfortably established as ruler of a half-Barbarian Greek city and seemed to have pillaged Persia "largely for the pleasure of it." Other say Alexander was partly driven by his desire to emulate Achilles and Hercules.

Before setting out on his mission of conquest Alexander arrived unannounced at the Oracle of Delphi. He demanded to see the seeress, and when she refused he dragged her into a temple and forced her to tell his prophecy. Plutarch writes: "As if conquered by his violence, she said, 'My son, thou art invincible.'"

See Separate Article: ALEXANDER THE GREAT'S MARCH OF CONQUEST europe.factsanddetails.com

Was It Alexander’s Army Rather Than Alexander That Was So Great

Alex Mann posted on Quora.com in 2023: Alexander the Great’s Army was leagues ahead of every other Army on earth. There was no close second. Alexander himself gets the credit but I don’t think this is fair. I honestly think Alexander was “meh” and won thanks to his great Army. Alexander’s Army was capable of things nobody else could do. They could fight in the trenches, outmaneuver an enemy, perform complex tactical actions, and do it all with ease. These guys were the most experienced, best-trained, and most elite soldiers on planet earth. In a time when armies were civilian-based militia with a small core of trained troops, Alexander had a professional Army at his back. [Source Alex Mann, Historian, M.A. Social Sciences & History, University of Mississippi]

Most give credit to Alexander and his brilliance but I disagree with this. Alexander made mistakes. At the Battle of Granicus Alexander recklessly charged across a river with a waiting enemy Army on the other side. This would have been a disaster for any other Army in history except Alexander’s and even Alexander’s Army took way too many losses.

Alexander was overconfident. In engineering, there is an acronym called “KISS” which stands for keep it simple stupid. Warfare is much the same. If tactics are overly complex then it creates situations where things could go wrong. No plan survives contact with the enemy so plans need to be simple and flexible.

Alexander didn’t create anything. This great Army Alexander had — it was created by his dad. These guys also gained experience fighting for Alexander’s father. Alexander didn’t unite Greece nor was attacking Persia his idea. Sure Alexander did conquer Persia however his Empire immediately fell apart because he was a terrible King and a terrible State-builder.

Alexander was wreckless personally. Alexander’s job was the lead the men, not fight with them. Yet Alexander led every battle from the front. Sure this is brave and all but this is the wrong place for a General. In an Army of 50,000 there are lots of fighters but only 1 leader. Caesar for instance would place himself behind the crux of the battle, issuing orders and watching as things develop.

Alexander the Great’s father was Phillip the 2nd. This guy fought and won dozens of Battles and conquered all of Greece for the first and only time. Was Phillip the greatest General ever? No. Like Alexander, Phillip benefited from a highly experienced, highly trained, and uber-expensive professional Army.

Alexander the Great's Army

Alexander's army was made up of around 50,000 men (an enormous number at that time when great cities had a population of 10,000 or 20,000). Most were Macedonians or hired Greek mercenaries that were paid in booty from the conquests. As time went on the Greeks were dropped and the army was made up mostly of Macedonians or subjects of the most recently conquered territory.

Taking over an army that his father Philip II had put together to invade Persia, Alexander crossed from Europe into Asia at Hellespont in 334 B.C. with an army made up of approximately 48,100 soldiers, 6,100 cavalry, and a fleet of 120 ships with crews numbering 38,000 drawn from Macedon and various Greek city states, mercenaries, and feudally raised soldiers from Thrace, Paionia, and Illyria. Alexander also did something that some say no general before him had done before: He incorporated conquered enemies into his army, thus growing his forces as he moved along. Cambridge historian Nicholas Hammond told National Geographic, "Alexander kept his army supplied by recruiting from the enemy. The fact that he could successfully do this speaks volumes about his leadership." [Source Wikipedia, Quora.com]

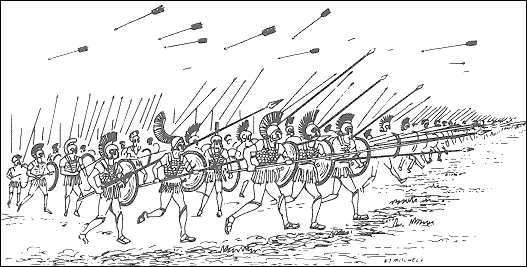

Alexander's force is regarded as the first professional army. At the vanguard were the Companions, an elite highly-skilled cavalry force, and the Macedonian phalanx, a high mobile unit of foot soldiers with long pikes. Cavalry made up about a sixth of the army. The Macedonians had a much more developed cavalry than the Greeks in part because Macedonia had more grasslands to feed horses. Genghis Khan and Alexander had similar-sized armies.

The main components of Alexander the Great’s army were: 1) Foot Companions were members of the regular infantry: These guys wielded a very long spear/pike and a small shield. Now at this time, everyone fought with a shield and spear however most spears were rather small. It took years of training for the soldiers to learn to use the pikes. Additionally, these guys were all trained in small unit tactics, hand-to-hand combat, and all sorts of special stuff. 2) Companion Cavalry The Companion Cavalry was arguably the greatest cavalry unit and certainly the best at the time. Cavalry at this time were mostly scouts and fast-moving infantry. They couldn’t really charge into enemy lines given stirrups were not around. Alexander’s cavalry was unique. These guys were trained for years and years on fighting on horseback. They could charge an enemy head-on, flank around them, or dismount and fight as infantry. They were the elite of the elite. 3) Shield Bearers were the “SpecOps” of the Macedonian Army. These guys fought like standard infantry with shorter spears, swords, and shields. They were hyper-flexible, extremely well trained, and capable of nearly anything. [Source Alex Mann, Historian, M.A. Social Sciences & History, University of Mississippi]

phalanx

Weapons of Alexander the Great's Army

Among the foot soldiers were archers, equipped with short bows; Greek hoplites, skilled veteran soldiers; shield bearers, who carried weapons and assisted the hoplites; slingers, who threw stones with slings; and trumpeters who relayed messages on the battlefield.

Alexander's soldiers relied on the sarissae , or pike, a 4.3-meter-long spear that was twice as long as a standard spear. Archers used powerful short bows. Slingers threw stones to harass the enemy. Soldiers were armed with swords and wore armored helmet and breastplate like the Greeks and used a round shield for protection. The cavalry rode horses with rudimentary saddles with no stirrups.

While the Persians and others relied on long bows the Greeks amd Macedonians were primarily hand-to-hand combatants who relied on swords and thrusting pikes. Sarissae were wooden pikes. They were generally around three meters longer than the average spear and this gave them a range advantage.

Alexander the Great's Encounters with Biochemical Weapons

Adrienne Mayor wrote in National Geographic History: In 326 B.C., Diodorus of Sicily, Strabo, and Quintus Curtius reported that Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army encountered poison projectiles in Pakistan and India. The warriors defending the city of Harmatelia had tipped their weapons with a poison derived from dead snakes left to rot in the sun. As the animals’ flesh decomposed, their venom supposedly suffused the liquefying tissue.[Source: Adrienne Mayor, National Geographic History, May 25, 2023]

Diodorus’s description of the agony of the wounded is vivid. Alexander’s soldiers first went numb, then suffered stabbing pains and wracking convulsions. Their skin became cold, and they vomited bile. Gangrene spread rapidly, and the men died a horrible death. Diodorus’s details allowed historians to determine that the venom came from the Russell’s viper. Its venom causes numbness and vomiting, then severe pain and gangrene before death, just as described in Diodorus’s accounts.

In 333 B.C., Alexander the Great’s army faced another devastating unconventional weapon. The Phoenicians defending Tyre (in Lebanon) ingeniously heated sand in shallow bronze bowls. Then they rained the red-hot sand down onto Alexander’s men. Ancient historians describe the ghastly scene as the hot grains sifted under the soldiers’ armor and burned deeply into their flesh, causing agonizing death. The burning shrapnel anticipated the fatal, deep burns inflicted by modern thermite or white phosphorus bombs, invented more than 2,000 years later and recently used in the same geographic region.

Supply Lines for Alexander the Great's Army

Supplying an army of 50,000 men was no easy task. Alexander employed bullocks and oxen (young and old castrated bulls) to carry the supplies, and the tactical range of his army was eight days, the maximum length of time in which an ox can carry supplies and food for itself. Campaigns of longer duration had to stay near ports (where food could delivered) or at settlements that were large enough to supply Alexander's army with what it needed. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Toni Tolis posted on Quora.com: Alexander used the Greek fleet to forward supplies to the army and marched alongside rivers to expand the reach of his naval vessels . He made alliances with cities in his way to establish forward bases and provide the means needed for his army to quick march between destinations. Most cities surrendered without fight as they were caught in surprise due to the swiftness of the Greeks and because the destruction of the city of Thebes had instilled fear in a lot of them. Oftentimes he would double march his forces just to conserve supplies and time needed to move. He could keep that pace because his army was very well trained , literally a mean, lean fighting machine revolving around Pezehtairos and his formidable long spear the sarisa.

Evangelos Lolos posted on Quora.com in 2022: The basis for Alexander’s logistical system was the Macedonian army which he inherited from his father, king Philip. Under Philip the use of slow-moving oxen-pulled carts was abolished and only the use of horses as pack animals was allowed. Men were expected to carry most of their equipment, such as weapons, tools, blankets and rations, most of which were carried in a backpack. As far as I know, they were the first army to do so. [Source Evangelos Lolos was born in the same region as Bucephalus and has a doctorate in Mathematics & History from University of Mississippi]

The army consisted of professionals, who were accustomed to these practices over many years of campaigns. Servants were allowed to accompany the higher status soldiers but were expected to be efficient; the usual “baggage train” of women and various other followers was strongly discouraged (although this policy was changed after the Persian defeat — the boost in morale was worth the speed penalty).

This system alone worked well for both Philip and Alexander during their European campaigns, which required fast paced marching to meet the enemy at a decisive battle. The Asian campaign however required a lot of planning, due to the longer distances involved and the multi-year campaign required to reach the objectives. Alexander initially had a big problem: his navy didn’t have control of the seas, so he couldn’t keep to the coast and get re-supplied by ship, the most efficient transport system of the time. So he did the following:

1) Extensively planned ahead, gathering intelligence about terrain, distances and features that might influence supply flow like mountain passes. Reading Xenophon or reports from the spy network established by his father also helped in that respect. 2) Stockpiled enough supplies and a treasury for the sole purpose of kick-starting his campaign, following through with his father’s plans. 3) Employed the top experts with the right skills. For example, his bematists gave distance estimates that are astonishingly accurate. He also assigned a dedicated senior officer in charge of the baggage train, responsible for the welfare of pack animals and the flow of supplies. Always made the replenishing or augmenting of his supply stockpiles a priority. For example, following Granicus, he marched to Sardis where he captured the treasury. He made alliances and also amended the Persian satrapy system by separating the tax collection function, thus ensuring he would get the revenue and supplies required.

He constantly created advance supply bases prior to campaigning so that the army would not have to spend time foraging. He knew when to take it slow. Rather than marching straight down the Royal Road from Sardis all the way to Susa, he took the long way around via Egypt and consolidated his power base and supply lines, something that worked well with his naval strategy.

He also adapted to local conditions. After passing Syria or Egypt, Alexander’s army purchased camels as pack animals which enhanced the supply capacity especially in the hot conditions of the Middle East. His soldiers' diet also had to include more dried food like dates and figs which were however readily available.

How Did Alexander the Great Feed and His Army During Their Campaigns

Alexander often relied on local resources as he marched through different regions. His army would forage for food, which included grains, fruits, vegetables, and livestock from the lands they traversed. To maintain a steady supply of food, Alexander established supply lines. These were critical for transporting food from established placed to where his army was at a given time.

Nitin Kumar posted on Quora.com in 2023:: Alexander the Great's army was fed through a complex system of supply lines and foraging during his conquests. As his army marched through different territories, they relied on a combination of captured food stores, agricultural resources, and hunting to sustain themselves. One of the primary sources of food for Alexander's army was the land they conquered. The army would pillage and plunder cities, taking any food or resources they could find. They would also demand tribute from conquered territories, which often included food supplies. This allowed the army to maintain a steady supply of food as they continued their march.

In addition to taking food from conquered territories, the army would also forage for food along the way. They would send out small groups of soldiers to scavenge for food in the surrounding areas, often finding wild game and edible plants. To supplement these sources, Alexander also set up supply lines that brought food from his home territory in Macedon. These supply lines would often include provisions such as grain, wine, and olive oil.

Overall, Alexander's army had a diverse diet that included meat, bread, fruit, vegetables, and dairy products. They would cook their food over open fires using pots and pans, and would also sometimes roast meat on spits. Feeding tens of thousands of soldiers was a logistical challenge, but Alexander's army managed to do so through a combination of conquest, foraging, and supply lines. By relying on a variety of food sources, they were able to maintain their strength and continue their conquests.

Michael D. Settles posted on Quora.com in 2017: Most ancient armies did not use modern supply lines, but rather would ‘live off the land’ of the areas they moved through and conquered. But they were not necessarily taken by force. Alexander would generally get cities to surrender on his approach (after destroying Thebes as an example), and pledge support (food and supplies) that allowed him to move forward. Alexander would cultivate friendly relations with those conquered to ensure continuity of supplies from the rear. He also moved swiftly in his campaigns, eliminating the normal “baggage train” of family, wives, furniture, servants, etc. [Source Michael D. Settles is retired from the U.S. Army]

Until fairly recently, armies foraged as they marched. They basically operated like swarms of locusts in the areas that they moved through. They took basic services with them, such as metal smiths, arrow-makers (fletchers), teamsters with horse/mule or oxen-drawn carts, etc. Most soldiers earned little or no pay; their compensation was whatever loot they could strip from dead enemies or villages they occupied or transited.

Alexander the Great's Military Tactics

Alexander liked to strike quickly. Some credit him with perfecting the cavalry charge. He often ignored the advise of his generals who advised caution and seemed little worried if his enemies held the high ground or some other advantageous military position.

At the heart of Alexander's army were rows of disciplined soldiers with pikes, spears and swords that were organized into a “phalaiazn” and were capable of overpowering far larger enemy groups. The front rows were armed with sarissaes which had a longer reach than their opponents. Rear troops pushed forward and helped the front-row troops press ahead. Archers, slingers and cavalry attacked and defended the sides.

Foot soldiers in Alexander the Great's army learned to withstand chariot advances by aiming their weapons at the horses first: by employing arrow-proof armor and shields; and by organizing themselves into tight chariot-proof ranks.

Alexander conducted at least 20 sieges, but none within Persia because the empire was supposedly guarded from its perimeter. The three main battles — Granicus, Issua and Guagamale — were fought in open country.

Alexander relied heavily on spies. He also purportedly spied on his own soldiers by intercepting their outgoing mail. According to legend, Alexander was the first commander to require that all of his soldiers be cleanly shaven. This was so that enemies could have nothing to hold on to. ◂

Civilians were often targeted, especially in Lebanon and the Indus Valley, where large number of innocent people were killed for no military reason. The historian Ernst Badian told National Geographic, "Blood was the characteristic of Alexander's whole campaign. There is nothing comparable in ancient history except Caesar in Gaul."

Alexander the Administrator

Alexander showed some skill as an administrator. He tolerated local customs and appointed local administrators. He appointed Persians to many posts and adopted the Persian style of administration even though Persians had long been his sworn enemies. He even wore local clothes of the Persians to earn support of the Persian people, something the soldiers that fought under him took offence to.

Administrative realities sometimes clashed with codes that kept military moral high. Alexander welcomed some Persians into his inner circle and even ordered a royal funeral for his main adversary, Darius III. These moves infuriated some of Alexander's soldiers and paved the way for a mutiny. Green wrote in his biography Alexander of Macedon “the sight of their young king parading in outlandish robes, and in intimate terms with the quacking, effeminate barbarian nobles he had so lately defeated, filled [his troops] with disgust." Alexander also angered those close to him by ordering the death of Parmenion, a loyal and venerated general who fought under Phillip and Alexander. and Callisthenes, Aristotle's nephew.

When Alexander learned that soldiers were plotting to kill him, he arrested seven of the alleged conspirators, including Philotas , the son of Parmenion. Although the evidence against Philotas was weak he and the others were stoned to death. In a pre-emptive move to stem a revenge attack, Alexander also had the 70-year-old Parmenion stabbed to death. From then on “Alexander never trusted his troops," Green told Smithsonian magazine, “The feeling was mutual."

Alexander and His Military Commanders

Plutarch wrote: “Noticing, also, that among his chief friends and favorites, Hephæstion most approved all that he did, and complied with and imitated him in his change of habits, while Craterus continued strict in the observation of the customs and fashions of his own country, he made it his practice to employ the first in all transactions with the Persians, and the latter when he had to do with the [220] Greeks or Macedonians. And in general he showed more affection for Hephæstion, and more respect for Craterus; Hephæstion, as he used to say, being Alexander’s, and Craterus the king’s friend. And so these two friends always bore in secret a grudge to each other, and at times quarrelled openly, so much so, that once in India they drew upon one another, and were proceeding in good earnest, with their friends on each side to second them, when Alexander rode up and publicly reproved Hephæstion, calling him fool and madman, not to be sensible that without his favor he was nothing. He rebuked Craterus, also, in private, severely, and then causing them both to come into his presence, he reconciled them, at the same time swearing by Ammon and the rest of the gods, that he loved them two above all other men, but if ever he perceived them fall out again he would be sure to put both of them to death, or at least the aggressor. After which they neither ever did or said any thing, so much as in jest, to offend one another. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

ancient mechanical artillery

“There was scarcely any one who had greater repute among the Macedonians than Philotas, the son of Parmenio. For besides that he was valiant and able to endure any fatigue of war, he was also next to Alexander himself the most munificent, and the greatest lover of his friends, one of whom asking him for some money, he commanded his steward to give it him; and when he told him he had not wherewith, “Have you not any plate then,” said he, “or any clothes of mine to sell?” But he carried his arrogance and his pride of wealth and his habits of display and luxury to a degree of assumption unbecoming a private man, and affecting all the loftiness without succeeding in showing any of the grace or gentleness of true greatness, by this mistaken and spurious majesty he gained so much envy and ill-will, that Parmenio would sometimes tell him, “My son, to be not quite so great would be better.”

“For he had long before been complained of, and accused to Alexander. Particularly when Darius was defeated in Cilicia, and an immense booty was taken at Damascus, among the rest of the prisoners who were brought into the camp, there was one Antigone of Pydna, a very handsome woman, who fell to Philotas’s share. The young man one day in his cups, in the vaunting, outspoken, soldier’s manner, declared to his mistress, that all the great actions were performed by him and his father, the glory and benefit of which, he said, together with the title of king, the boy Alexander reaped and enjoyed by their means. She could not hold, but discovered what he had said to one of her acquaintance, and he, as is usual in such cases, to another, till at last the story came to the ears of Craterus, who brought the woman secretly to the king. When Alexander had heard what she had to say, he commanded her to continue her intrigue with Philotas, and give him an account from time to time of all that should fall from him to this purpose. He thus unwittingly caught in a snare, to gratify sometimes a fit of anger, sometimes a mere love of vainglory, let himself utter numerous foolish, indiscreet speeches against the king in Antigone’s hearing, of which though Alexander was informed and convinced by strong evidence, yet he would take no notice of it at present, whether it was that he confided in Parmenio’s affection and loyalty, or that he apprehended their authority and interest in the army.”

Alexander the Great's Speech to His Army

The “Anabasis of Alexander” was composed by Arrian of Nicomedia (A.D. 92-175), a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period. It is considered the best source on Alexander the Great’s the campaigns. It records the following speech by Alexander: “I observe, gentlemen, that when I would lead you on a new venture you no longer follow me with your old spirit. I have asked you to meet me that we may come to a decision together: are we, upon my advice, to go forward, or, upon yours, to turn back? [Source: Arrian, “Anabasis of Alexander”, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“If you have any complaint to make about the results of your efforts hitherto, or about myself as your commander, there is no more to say. But let me remind you: through your courage and endurance you have gained possession of Ionia, the Hellespont, both Phrygias, Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, Lydia, Caria, Lycia, Pamphylia, Phoenicia, and Egypt; the Greek part of Libya is now yours, together with much of Arabia, lowland Syria, Mesopotamia, Babylon, and Susia; Persia and Media with all the territories either formerly controlled by them or not are in your hands; you have made yourselves masters of the lands beyond the Caspian Gates, beyond the Caucasus, beyond the Tanais, of Bactria, Hyrcania, and the Hyrcanian sea; we have driven the Scythians back into the desert; and Indus and Hydaspes, Acesines and Hydraotes flow now through country which is ours. With all that accomplished, why do you hesitate to extend the power of Macedon — your power — to the Hyphasis and the tribes on the other side ? Are you afraid that a few natives who may still be left will offer opposition? Come, come! These natives either surrender without a blow or are caught on the run — or leave their country undefended for your taking; and when we take it, we make a present of it to those who have joined us of their own free will and fight on our side.

“For a man who is a man, work, in my belief, if it is directed to noble ends, has no object beyond itself; none the less, if any of you wish to know what limit may be set to this particular camapaign, let me tell you that the area of country still ahead of us, from here to the Ganges and the Eastern ocean, is comparatively small. You will undoubtedly find that this ocean is connected with the Hyrcanian Sea, for the great Stream of Ocean encircles the earth. Moreover I shall prove to you, my friends, that the Indian and Persian Gulfs and the Hyrcanian Sea are all three connected and continuous. Our ships will sail round from the Persian Gulf to Libya as far as the Pillars of Hercules, whence all Libya to the eastward will soon be ours, and all Asia too, and to this empire there will be no boundaries but what God Himself has made for the whole world.

“But if you turn back now, there will remain unconquered many warlike peoples between the Hyphasis and the Eastern Ocean, and many more to the northward and the Hyrcanian Sea, with the Scythians, too, not far away; so that if we withdraw now there is a danger that the territory which we do not yet securely hold may be stirred to revolt by some nation or other we have not yet forced into submission. Should that happen, all that we have done and suffered will have proved fruitless — or we shall be faced with the task of doing it over again from the beginning. Gentlemen of Macedon, and you, my friends and allies, this must not be. Stand firm; for well you know that hardship and danger are the price of glory, and that sweet is the savour of a life of courage and of deathless renown beyond the grave.

“Are you not aware that if Heracles, my ancestor, had gone no further than Tiryns or Argos — or even than the Peloponnese or Thebes — he could never have won the glory which changed him from a man into a god, actual or apparent? Even Dionysus, who is a god indeed, in a sense beyond what is applicable to Heracles, faced not a few laborious tasks; yet we have done more: we have passed beyond Nysa and we have taken the rock of Aornos which Heracles himself could not take. Come, then; add the rest of Asia to what you already possess — a small addition to the great sum of your conquests. What great or noble work could we ourselves have achieved had we thought it enough, living at ease in Macedon, merely to guard our homes, accepting no burden beyond checking the encroachment of the Thracians on our borders, or the Illyrians and Triballians, or perhaps such Greeks as might prove a menace to our comfort ?

“I could not have blamed you for being the first to lose heart if I, your commander, had not shared in your exhausting marches and your perilous campaigns; it would have been natural enough if you had done all the work merely for others to reap the reward. But it is not so. You and I, gentlemen, have shared the labour and shared the danger, and the rewards are for us all. The conquered territory belongs to you; from your ranks the governors of it are chosen; already the greater part of its treasure passes into your hands, and when all Asia is overrun, then indeed I will go further than the mere satisfaction of our ambitions: the utmost hopes of riches or power which each one of you cherishes will be far surpassed, and whoever wishes to return home will be allowed to go, either with me or without me. I will make those who stay the envy of those who return.

Macedonia While Alexander Was Gone

When Alexander set out for Asia, he left his general Antipater, an experienced military and political leader, and part of Philip II's "Old Guard", in charge of Macedon. Alexander's sacking of Thebes ensured that Greece remained quiet during his absence. The one exception was a call to arms by Spartan king Agis III in 331 BC, whom Antipater defeated and killed in the battle of Megalopolis. Antipater referred the Spartans' punishment to the League of Corinth, which then deferred to Alexander, who chose to pardon them. There was also considerable friction between Antipater and Olympias, Alexander’s motherm each complained to Alexander about the other.

Olympias remained in Macedonia during Alexander’s absence. She regularly corresponded on public as well as domestic affairs, with him. Her great influence and ambition caused much trouble. Elizabeth Carney wrote in National Geographic History: As Alexander’s victories accumulated, Alexander sent plunder home to Olympias, and she made splendid dedications in his honor at Delphi and Athens. Tradition says that she offered advice to her son while he was away and warned him of threats.Antipater and Olympias seems to have thought that the other was overstepping their position. Ancient authors describe Olympias as difficult and assertive and insist that Alexander tolerated his mother but did not let her affect policy. At least not at first; toward the end of his reign it was different. By 330 B.C. quarrels with Antipater forced Olympias to retreat to Molossia. [Source: Elizabeth Carney, National Geographic History, December 4, 2019]

In general, Greece enjoyed a period of peace and prosperity during Alexander's campaign in Asia. The vast sums that Alexander sent back from his conquest stimulated the economy and increased trade across his empire. However, Alexander's constant demands for troops and the migration of Macedonians throughout his empire depleted Macedon's strength, greatly weakening it in the years after Alexander, and ultimately led to its subjugation by Rome after the Third Macedonian War (171–168 B.C.)

Why Didn't Alexander the Great Invade Rome?

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Alexander the Great conquered a massive empire that stretched from the Balkans to modern-day Pakistan. But if the Macedonian king had turned his attention westward, it's possible he would have conquered Rome, too, feasibly smiting the Roman Empire before it had a chance to arise. So why didn't Alexander the Great try to conquer Italy? The answer may be that he died before he got the chance. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, November 25, 2023]

Had he not died, however, it's possible that Alexander would have targeted Rome and, with his substantial forces, defeated the Eternal City. Some ancient texts suggest that Alexander the Great was planning a military campaign in the West that involved conquering parts of Italy, among other locations along the Mediterranean. The Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus, who lived in the first century A.D., claimed that Alexander the Great had planned a series of conquests that, if successful, would have expanded his empire all the way to what is now the Strait of Gibraltar. Alexander planned to build 700 ships to support this invasion, Rufus noted. Other ancient writers made similar claims. "The Romans were convinced that Alexander would have attempted the conquest of Rome, but for modern historians, it is impossible to say," Nikolaus Overtoom, an associate professor of history at Washington State University.

Some ancient writers claimed that after Alexander died, his secretary, Eumenes, gave one of Alexander's senior generals, Perdiccas, plans that included the conquest of part of Italy, Robin Waterfield, an independent scholar with a background in classics, t. "Now, some scholars believe that the [plans] are not genuine — perhaps a forgery by Eumenes, or perhaps the whole story arose years, even decades later," Waterfield said. However, "I think the balance of evidence is that they're genuine."

It's ultimately unclear what would have happened if Alexander the Great had tried to invade Italy. The Romans were so strongly convinced that Alexander would have attempted the invasion that the historian Livy (lived circa 59 B.C. to A.D. 17) wrote a text speculating how the invasion would have ended, with Livy predicting that the Romans would have defeated Alexander. Livy noted that Alexander's uncle, Alexander I of Epirus, who ruled a kingdom of the same name, tried to conquer part of Italy but was killed in battle in 331 B.C.

Waterfield noted that descriptions of Alexander's plans indicate he would have invaded other locations in the Mediterranean before landing on the Italian mainland. This suggests that Alexander's forces would have been overwhelming, even if the Romans had any allies in their fight against him. "By the time he reached Italy and faced the Roman Republic he would have had the resources of the entire Mediterranean at his command — a vast mercenary army, and he'd have commanded all the supply routes," Waterfield said. The "only thing that could have stopped him was internal rebellion or mutiny by his Macedonian troops."

Philip Freeman, a humanities professor at Pepperdine University in California, said that if Alexander had invaded Italy, he likely would have succeeded, noting that there were a number of Greek colonies in Italy that might have supported Alexander's rule. "The Romans were tough and would have resisted, but they were not yet the powerful force of later centuries," Freeman t. "If Alexander had invaded, I think there would have been no Roman Empire since Roman power would have been nipped in the bud, so to speak."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024