ANCIENT GREEK NAVY

The ancient Greek navy was made up primarily of oarsmen on trireme ships (See Below). Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: The Athenian fleet boasted more than 50,000 oarsmen, few of whom were slaves or foreigners. Most of them belonged to the class of thetes, citizens of the wage-earning class who could not cover the cost of arming themselves, as soldiers were required to do. The development of the navy as a bulwark of Athenian democracy in the fifth century B.C. raised this social class’s influence in relation to the aristocracy. It is no coincidence that Greek philosophers like Plato and Euenus and Athenian citizens began to refer to their leaders as “helmsmen” who guided the “ship of state.” [Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

The Greek navy needed to be able to count on thousands of such sailors, which explains why their extraordinary strength, ferocity, and loyalty was well rewarded. They received comparatively high wages and a social status that reflected their importance in ancient Athens.

The fleet’s departure, commanded by one or more naval commander (strategoi), was an important event. Their training enabled the crew to get in position and check that the ship, their tools, and weapons were in good working order quickly: within just 30 seconds, according to a modern simulation. A priest officiated at an animal sacrifice before the captain offered a prayer and hymn to the gods. Finally, a cup of wine was poured over the ship’s bow and stern as a libation.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT GREEK MERCHANT SHIPS: TYPES, CARGOES, SHIPWRECKS europe.factsanddetails.com

SEA TRAVEL AND NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT GREEK MILITARY factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SOLDIERS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK WEAPONS AND ARMOR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK ARMY: UNITS, ORGANIZATION, SUPPLY LINES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WARFARE IN ANCIENT GREECE: BATTLES. TACTICS, METHODS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy” by John R. Hale (2009) Amazon.com;

“Rulers of the Sea: Maritime Strategy and Sea Power in Ancient Greece, 550–321 BCE” by John Nash (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Athenian Empire” by Russell Meiggs (1972) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Oared Warships 399-30BC” by John Morrison (2016) Amazon.com;

On Ancient Galleys: And Their Mode of Propulsion

by William Schaw Lindsay (1871) Amazon.com;

“Warships of the Ancient World: 3000–500 BC” by Adrian K. Wood, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator) (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Warship: 500–322 BC” by Nic Fields and Peter Bull (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Athenian Trireme: The History and Reconstruction of an Ancient Greek Warship”

by J. S. Morrison , J. F. Coates, et al. (2000)

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Anabasis” by Xenophon (1847) Amazon.com;

“Financing the Athenian Fleet: Public Taxation and Social Relations” by Vincent Gabrielsen (2010) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic and Roman Naval Wars, 336 BC–31 BC”

by John D. Grainger Amazon.com;

“The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter that Saved Greece -- and Western Civilization” by Barry Strauss (2005) Amazon.com;

“Salamis 480 BC: the Naval Campaign That Saved Greece” by William Shepherd and Peter Dennis (2010) Amazon.com;

Amazon.com;

“A Naval History of the Peloponnesian War: Ships, Men and Money in the War at Sea, 431-404 BC” by Marc G. de Santis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sea of Flames: A thrilling account of the Battle of Actium” (2024) by Alistair Forrest Amazon.com;

“Actium 31 BC: Downfall of Antony and Cleopatra” by Si Sheppard (Author), Christa Hook (Illustrator) (2009) Amazon.com;

“The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium”

by Barry Strauss Amazon.com;

“Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities” by Hans Van Wees (2004) Amazon.com;

“Greek Fire, Poison Arrows and Scorpion Bombs” by Adrienne Mayor (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Economics of War in Ancient Greece” by Roel Konijnendijk and Manu Dal Borgo | (2024) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece” by Tim Everson (2004) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Michael M. Sage (1996) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek Fighting Ships

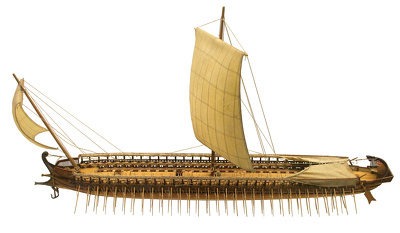

Ancient Greek fighting ships were built of wood and had shelters to protect the crew from the fierce Mediterranean sun. Over the open sea they traveled using hand-woven square sails. The oars were mainly for powering and maneuvering the ships in battles. At the bow was a bronze ram that was used to batter and pierce enemy ship's sides and sink it. Their main objective was to clear away enemy ships so an army could land. [Source: Timothy Green, Smithsonian magazine, January 1988]

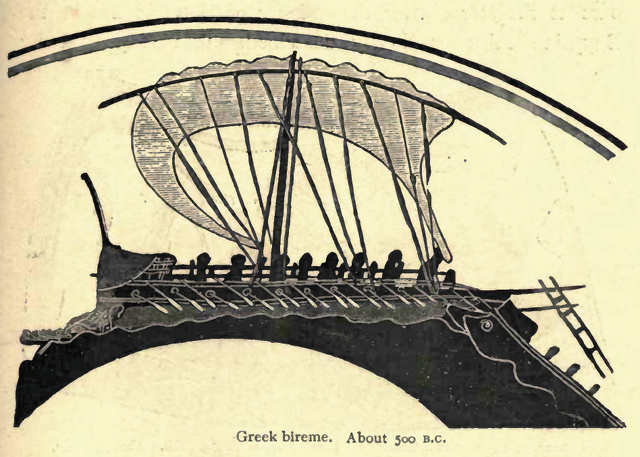

Even in the heroic period fairly good ships were built, though they were better suited for coasting than sailing in the open sea. They were moved by twenty to fifty sailors, seated on thwarts on either side of the ship, while their oars were suspended in leathern straps between the rowlocks; if the wind was favorable, they replaced the oars by a sail suspended from the mast by a sail-yard; in the stern, the helmsman directed the course of the ship with the rudder. The ship of Odysseus was thus represented, even in later art, cutting its way through the sea. Still, this picture, which dates from a much later period, cannot give us a proper conception of the build of the Homeric ships: we should rather turn to the representations from ancient vases on two images, in spite of the roughness and smallness of the drawing. Both these have a strong spur at the prow, and were, therefore, apparently used for naval warfare, with which the Homeric age was not yet acquainted. Probably the ships of the heroic age had high projecting ends both forward and aft.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Between 1150 B.C. and 850 B.C., the first ships with battering rams appeared and they shaped the way naval battles were fought for the next 1,500 years. The bow-based bronze rams transformed galleys from troop transports and coastal raiders into ships that were capable of fighting at sea. The "rams forced the construction of heavier vessels, and the tactics of ship-to-ship combat favored the development of faster and more maneuverable boats."

Parts of an Ancient Greek Fighting Ship

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: The trireme’s most feared weapon was a bronze battering ram attached to the prow of the ship. Fierce ancient naval battles were fought by trying to slam into the side of an enemy ship and either puncture the hull or damage the oars to immobilize it. Scholars estimate the maximum ramming speed to be around nine knots (10.4 miles an hour). [Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

As to the construction of the ships, the prow and stern were, generally speaking, of similar build; both, as a rule, ended in curves, but there was usually a lofty decoration of leaves or feathers for the stern, while at the prow they put the image of a god, or the head of an animal, or some other picture, which often showed the name of the boat; these were constructed of wood or bronze, and a flag waved at the top. Below the prow, for the most part under water, lay the strong beak, made of boards firmly fastened into the bow, and protected in front by massive iron points. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

On the deck there was usually a little canopy at both ends; in one image this is seen on the front deck, and apparently also in another image, though this may be a little tent used as a protection against the sun, such as was often placed on the upper deck. The tower at the back, and the little hut for the helmsman from which he directed both rudders, are wanting on these pictures. The old ships had two rudders, to the right and left of the stern; by means of a mechanical contrivance, which is, however, not represented in the pictures, these two rudders could be directed at the same time in a parallel direction.

In some images we observe near the bow a round opening, corresponding to a similar hole in another image; the object of this was to enable the anchor-ropes to pass through the ship to the anchors, which resembled our modern ones in all essentials, and were hung up when not in use on little projections at both sides of the prow, which also served the purpose of keeping off the enemy’s ship when avoiding an attack. On the great mainmast there were, as a rule, two square yard sails, fastened one over another, with a third above them, and at the top of the mast two triangular topsails. The ships of war also had two sails following the length of the ship, which were of particular importance for turning when the wind blew from the side. The Attic inscriptions give us many other details about seafaring, but these are only of special interest for professional sailors.

Types of Ancient Greek Fighting Ships

Before about 800 B.C., there was no leading ship type used within the fleets of the Aegean. Most of the ships were little more than large boats of ancient design. They were mainly used in war to carry troops. Naval battles were plank actions. Around 800 B.C. naval battles became competitions of maneuvering and speed. The kind of ship that facilitated this was the Pentecost, a a fast war galley with oarsmen. A krater from circa 735 B.C. shows Ariadne and Theseus boarding a ship with two rows of oars.

Homer's epic poem The Iliad, written in the eighth century B.C., mentions triaconters and penteconters, vessels that were crewed by 30 or 50 men, respectively. A large pentecontor could be up to thirty-seven to thirty-eight meters; the grin would be 4 meters to allow room for the rowers to work the oars. Such ships had a speed of nine to ten knots. There was also a small war galley, used by marines of the Aegean.[Source: According to Greeceme.com].

Biremes (galleys with double banks of oars) first appeared 700 B.C. and are recorded on reliefs from that time. They were created when someone came up with the idea of using outriggers. This allowed for two rows of oars. The lower row of oars was fixed directly to the hull and worked just like in earlier ships. The upper row of oars were fixed with the outriggers as well as the higher oarsmen sat further outside, giving area for both rows of oars to function. Biremes had a narrow beam compared to Penteconters of similar length, with most of them having a beam of 3 meters. Most Biremes carried a hundred rowers.

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: At the beginning of the seventh century B.C., accumulated experience led to new technical advances, and the much more sophisticated trireme model appeared. Thucydides wrote that the Corinthians were the first to introduce the design to the Greek world, though modern historians think triremes may have first been built in Phoenicia, in the eastern Mediterranean and what is now Lebanon.

Triremes (galleys with triple banks of oars) first appeared 500 B.C. but the cost of building them was so great that they were not widely used until around the time of Alexander (the 4th century B.C.). Not much is known about the designs of these ships other than what can be gleaned from historical accounts and few images on vases. No remains of a trireme have ever been found.

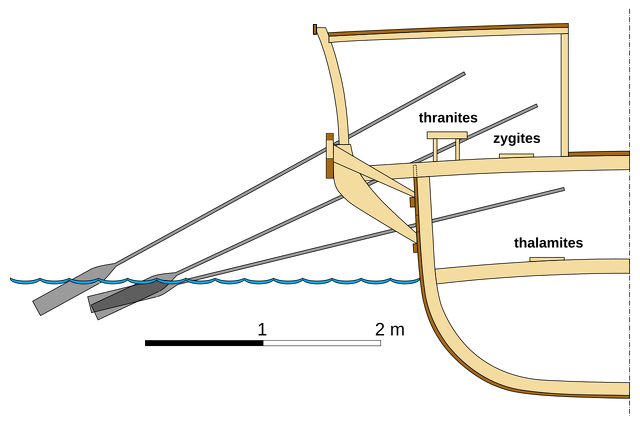

In later times, especially after the fourth century B.C. , there were four or even six rows, and possibly still more. The arrangement of these rowers’ benches is of particular interest, and is made tolerably clear by the Athenian relief. The rowers’ benches occupied the whole space of the two long sides of the ship, with the exception of the two ends; they were arranged over one another in rows of different heights, not separated by partitions, but only by the open structure of wood. In each row each rower sat immediately in front of the next man in a straight line, but there is a difference of opinion as to the manner in which the rowing benches were arranged. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Triremes

Triremes were the most famous warships of antiquity. Their name is derived from the Greek trieres, “three rows of oars”. These ships were used by Athenians to defeat the Persians at the Battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. A typical trireme is thought to have been a 118-foot-long vessel powered by sails and 170 oars mounted on three decks. The oars came in two lengths — 13 feet and 13 feet and 10 inches — and the oar holes were large enough for a man's head (a punishment that sometimes befell unruly oarsmen).

Triremes cruised at a speed estimated at between 7 and 12½ knots. They carried only 14 soldiers and a crew of 17 to go along with the 170 oarsmen. This because by the time they became widely used they were no longer troop carriers but were full-blown naval fighting ships.

Triremes were made for day use only. There were no facilities on them for eating or sleeping. Storage space was minimal. At night, the trireme was pulled out of the water, both to protect its hull from shipworms and to allow the crew to eat and rest. While ashore, the hull could also be checked for needed repairs.

Large Ancient Greek Ships

As time went the ships became larger and larger. Galleys rated as "fours," "fives," and "sixes" were introduced between 400 B.C. and 300 B.C. They were followed up by "16s," "20s" and "30s." The Emperor Ptolemy IV built a massive "40." The numbers refereed to the number pulling each triad of oars. Ships with more than three bank were built but ultimately they proved to be impractical.

Describing one of the largest boats, a 2nd century Greek wrote: "It was [420 feet] long, [58 feet] from gangway to plank and [72 feet] high to the prow ornament...It was double-prowed and double-sterned...During a trial run it took aboard over 4,000 oarsmen and 400 other crewmen, and on deck 2,850 marines."

Of course, the larger the ships the greater the number of oarsmen required, since the number of rows would be greater; a “trireme” was rowed by 174 men, a “quinquereme” by 310, the arrangement being that each higher row had two men more than the one below, because the bulk of the ship was broadened towards the top. In rowing the greatest regularity of movement was indispensable; this was attained by the command of a special captain, and also by marking time with flutes, so that all the oars might strike the water at the same moment. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Here we meet with a problem, hitherto unsolved: how was it possible for the long oars of the upper rows to keep stroke with the short ones of the lower rows? This would have been impossible if the same word of command was given to all the rowing benches, since the stroke of a long oar would naturally require more time than that of a short one. Another difficulty is the great number of oarsmen which would have been required for Attica, where the number of ships was very considerable; still, the number of sailors and marines was very small, as in naval warfare the main object was to sink the enemy’s ship by means of the prow, while they did not trouble much about shooting and fighting at a distance.

Fighting Triremes of Athens

With battering rams attached to their prow and a crew of nearly 200 oarsmen, triremes helped turn Athens what was arguably the world’s first naval superpower. Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: Fast, maneuverable, and dangerous, the trireme was the most feared ship in ancient Greece. With powerful bronze rams and the ability to turn on a dime, it would leave enemy ships dead in the water by punching holes in their sides or smashing their oars. In his Histories, Herodotus writes how Greek naval dominance owed so much to the brilliant use of triremes in battle. [Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

In the fifth century B.C., Athenian shipyards had the capacity for over 300 triremes The Greeks considered triremes to be living things, each endowed with a sacred character. For this reason, the ships were given individual names, which were almost always feminine. Their characteristic eyes located on both sides of the prow were used to “find their way through the sea,” the walkways protruding from the prow were their “ears,” and the sails were their “wings.”

Faster and more stable than their predecessors, triremes were expensive to produce. Manufacturing costs ran as high as more than one talent (6,000 drachmas, or 58 pounds of silver). If a ship were damaged in battle, it could still be put to good use. With proper maintenance, triremes could remain in service for 20 to 25 years before being decommissioned or sold as “war surplus.” History has recorded some that were sailing for more than 80 years.

The ships in the best shape were reserved for the military, while older ones were used mainly for surveillance and transportation. Athens had two prized triremes, the Salamina and the Paralo. Noted for their beauty, these flagships were often used for diplomatic missions or rituals, such as transporting Athenian athletes to the Olympic Games every four years.

Ancient Greek Ship Rowers

Contrary to the popular myth Greek fighting ships were not manned by slaves, who were thought to be untrustworthy and expensive (they had be fed year-round even though a ship only operated about half the year). Instead they were manned by free citizens who sat on three levels.

The oars were secured with leather straps. The rowers had to learn to row in unison so their oars didn’t collide. One rower said, "Because there are only nine inches between the blades any tiny discrepancy in a stroke caused one blade to hit the next and, and so on in a domino effect." When it is working well it was "like a centipede, with all oars moving beautifully."

The rowing stations at the center of the ship were best because if a oar is viewed as a lever and the oar hole is the fulcrum. According to the laws of mechanics the further one is away from the fulcrum the easier is to lift the object — or in the case of the oar, push the water.

Oarsmen on a Fighting Trireme

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: Paying the crew was a considerable expense. Wages were about one talent per month, an expense paid by the captain (trierarchos) from his own pocket. Keeping the crew well fed was crucial to their performance. A typical diet included salted fish, oatcakes, wine, cheese, vegetables, and about seven quarts of water per day.

The three levels were aligned on both sides, with the different levels to one side of each other to improve stability. The thalamites sat on the base of the hull and endured the worst conditions; the zygites were in the middle level; and at the top, the thranites had to make the greatest effort because of their higher position.

Under sail, the oarsmen followed the orders of the keleustés, issued by shouting or striking a piece of timber with a mace. When the roar of waves or battle prevented the rowing master from being heard, an aulos, a wind instrument like a double flute, marked the rowing beat. The oarsmen joined in with traditional chants to keep in time.

According to Graser, they were immediately under one another, but the rowers did not sit perpendicularly above each other; but in order to save space as much as possible, and partly to facilitate their movements, they were arranged in such a way that the seat of the next highest was in the same direction and height as the head of the man on the next seat below, so that each man, instead of sitting directly under the man above, sat a little towards the back, and, in moving, kept his arms immediately under the seat of the man above. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Lemaître, on the other hand, assumes that only the lowest benches were close to the edge, and those above were removed by the breadth of the thwart, the third by two breadths, in which case the height must have been so arranged that the oar of the man above always passed over the head of the one immediately below. It is impossible to attain any certainty about this matter; both hypotheses are open to objection. For the length of the oars naturally increased in proportion to the distance of the rowers from the water, and those of the highest row must have been longest; according to Graser’s arrangement, the length of the oars increased 1 yard for each row, so that in a ship of five rows the lowest rank had oars 2½ yards long, the highest 6½; according to the arrangement of Lemaître, the length was even greater, but there was this advantage, that the longer oars had also longer leverage, and could consequently be more easily controlled.

Lenormant Relief, from the Athenian Acropolis, depicting the rowers of an Athenian trireme, c 410 BC

The larger the number of rows, the greater in consequence was the length of the oars, but still they were able to build and control ships of fifteen or sixteen rows. The splendid ship of Ptolemy Philopater is said to have had no less than forty rows, and the length of the highest oars was 18½ yards; but this was not a ship of war, and was only used in calm water — in fact, a modern authority on seafaring regards the whole description of this forty-decker as a satire.

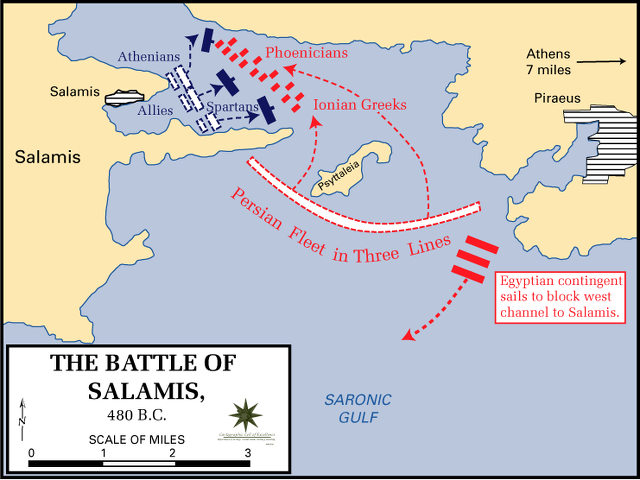

Ancient Greek Sea Battles

In naval clashes, the ancient Greeks preferred oared vessels over sailing ships because they were more maneuverable. Ships were used in conjunction with land forces to cut off coastal towns and keep large armies from landing. Almost all great naval battles from Salamis in 480 B.C. to Lepanto in and 1571 — were fought within sight of land. Maneuverability was an asset because naval clashes were essentially hand-to-hand land battles on water. Some of ships were outfitted with a battering ram bow and rowers who were stronger to propel their boat forward with enough force to sink with a broadside thrust on an enemy ship. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: A typical strategy was to ram an enemy ship and retreat quickly to let it sink. In the case of surrender (or when the attackers picked up the survivors before they drowned), captured oarsmen were allowed to change sides (experienced oarsmen were very valuable assets). If an attacking ship rammed a ship and became stuck in its side, each crew would be forced into combat with the goal of seizing the intact ship, while the vessel that had been rammed would be abandoned. [Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

Sea battles and commerce usually only took place in the summer. Aristophanes wrote: "When there is a threat of war, you didn't sit quiet; but in a moment you be launching 300 ships and the city would be full of the hubbub of servicemen, or shouts for... wage-paying...Down in on the dockyard the air would be full of the planing of oars, the hammering of dowel pins, the fitting of oarports with leathers, or popes, bosn's, trills and whistles."

During the winter the seas were too stormy and rough. Dozens of triremes would return to Athens in early winter. If dolphins swam off their bows, it was a good omen, as these animals were believed to save sailors from drowning. Each trireme underwent repairs and cleaning in port. The trierarchs presented reports of their missions, while sailors and oarsmen collected their wages.

Naval battles not only happened above water; they could also be fought under the sea. From the ninth century B.C., Greek navies were hiring divers who were capable of staying underwater for long periods of time, a feat similar to that undertaken by free divers today. Scyllias of Scione and his daughter Hydna were two such celebrated swimmers.

See Battle of Salamis Under PERSIAN WARS: HERODOTUS, SALAMIS AND ANCIENT GREEK VICTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Decline of the Ancient Greek Navy and Trireme Warfare

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: Greece’s naval dominance did not last forever, and the trireme evolved. Modifications to the trireme as a design were spearheaded by various Mediterranean powers, and put to the test in the period when the successors of Alexander the Great fought for dominance in the late fourth and early third centuries B.C. By the time of the First Punic War in the mid-third century B.C., Romans and Carthaginians were fighting at sea using quadriremes and quinqueremes.[Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

When the Romans conquered Macedonia in 168 B.C., they were surprised to discover an ancient trireme, left abandoned in a shipyard for 70 years. They considered it a relic, but so beautifully made that they reused it. History’s final recorded battle relying on the descendants of the trireme was the Battle of Lepanto off western Greece on October 7, 1571 — more than 2,000 years after triremes first sailed. The Holy League coalition of Spain and many Italian city-states smashed the Ottoman fleet, killing nearly half their 67,000 men.

The Battle of Lepanto was one of the last naval conflicts in the West to rely heavily on human-driven galleys; subsequent naval conflicts would be dominated by sail-powered craft. The vast deployment of craft that marked naval battles in antiquity was also becoming a thing of the past. Nearly 700 galleys took part in the Battle of Ecnomus between Rome and Carthage in 256 B.C. A total of around 70 vessels took part in the Battle of Trafalgar of 1805.

Olympias — Replica of a 170-Oar Trireme

In 1987 a team led by naval architect John Coates and Cambridge University professor John S. Morrison built the Olympias, a reproduction of a classic Athenian trireme. The English-Greek team built the 170-oar trireme at a cost of around $640,000. Held together with 20,000 tenons fastened with 40,000 oak pegs, it set sail with a an international crew of 132 men and 40 women. Describing, the team in action, Timothy Green wrote in Smithsonian, "the crew rowed together and sang together, getting up high spirits and up to seven knots.

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: The ship plied the Mediterranean, living up to her name. But her 170 oarsmen were only able to power the boat at a maximum speed of nine knots (10.4 miles an hour) for five minutes. Coordinating the crew was extremely difficult, even for professionals. [Source:Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

Moreover, when the Olympias faced headwinds with gusts of up to 25 knots (28.8 mph), the oarsmen on the lowest banks, the thalamites, struggled to keep rowing in rough surf and huge waves. The other oarsmen not only had trouble rowing in rhythm but also were physically exhausted after an hour. No doubt the preparation, training, and years of experience shared by trireme oarsmen of ancient Greece were far superior to the brief training of these modern sailors. The strenuous efforts of the modern sailors gives some idea of the incredible effort the Greeks were capable of exerting for hours on end at the height of battle.

Trireme Archaeology

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: Today archaeologists are keen to find any material remains of fifth-century B.C. triremes throughout the Mediterranean world. Because the ships were made of soft wood and susceptible to shipworms and decay, well-preserved wrecks are difficult, if not impossible, to find in the warm seawaters. [Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

The bronze rams, however, would survive centuries at the bottom of the sea, and archaeologists continue to comb the waters for them. One of the first and most significant discoveries was the so-called Athlit ram, discovered in 1980 near the village of Athlit, Israel. Giving great insight into how these weapons were forged, the heavy bronze ram weighs more than 1,000 pounds. It was found with timbers still attached from what is now believed to be a trireme or quadrireme from around the second century B.C.

One of the most valuable archaeological sites is the military port of Piraeus. Located about five miles from Athens, Piraeus was home to the mighty Athenian fleet at the height of its powers in the fifth century B.C. Archaeologists were thrilled to find the remains of several ancient boathouses (neosoikoi), which helped them better understand not only how triremes were built but also how they were maintained. The hunt continues for these former boats that ruled the Mediterranean and what they can reveal about the shipbuilding culture of ancient Athens.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024