Home | Category: Greek Classical Age (500 B.C. to 323 B.C.)

PERSIAN WARS

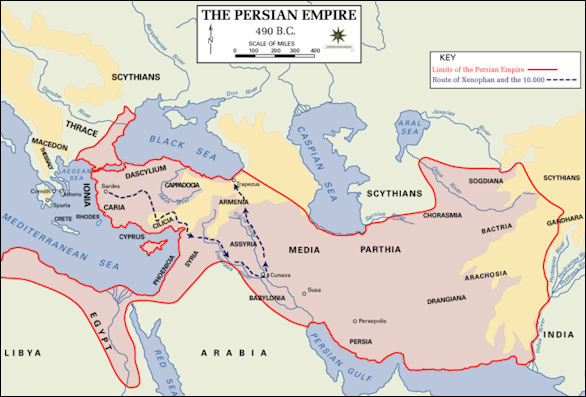

Between 499 to 479, Greece and Persia fought a series of wars that determined the balance of power in the Mediterranean. In 492 B.C., Persia was of one of the world's largest empires. It controlled a huge expanse of territory, including Greek cities in Asia Minor. Its expansion westward seemed inexorable. Greece, which consisted of bunch of disparate states that fought against one another more than they were united, seemed like an easy target.

The Persian Wars were triggered by a rebellion by Ionian Greeks in Asia Minor against their Persian lords and the Persian King Darius in 499 B.C.. Athens and Eretria supported the rebellions and Greeks sacked the important Persian city of Sardis. Darius was outraged. He asked “Who are these Athenians?” and then appointed a slave to remind him every day, “Master, remember the Athenians!” The Persians retaliated by destroying the Greek city of Miletos. Darius was further infuriated when he demanded symbolic tokens of “earth and water” from Athens and Sparta and the defiant Athenians threw the Persians envoy into a pit (“earth”) and the Spartans their envoy into a well (“water”).

Darius developed a plan to invade Greece and teach the Athenians a lesson they wouldn’t forget. The gods favored the Greeks during Darius’s first invasion. A fleet of 600 Persian ships crossed the Dardanelles and then was ravaged by storm off of Mount Anthos that destroyed half the fleet.

The military campaigns against the Greeks by Darius and, after his death, by his son Xerxes, constituted the largest military undertaking in history up to that time.

Aeschylus’ plays are the earliest accounts we have of the Persian Wars. The characters in his play “The Persians” are: 1) Atossa, widow of Darius and mother of Xerxes’ 2) a Messenger 3) Ghost of Darius; 4) Xerxes and 4) a Chorus of Persian Elders, who compose the Persian Council of State. The play begins at the Council-Hall of the Persian Kings at Susa. The tomb of Darius the Great is visible. The time is 480 B.C., shortly after the battle of Salamis. The play opens with the Chorus of Persian Elders singing its first choral lyric. [Source: University of Calgary]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DARIUS I (ruled 522-486 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

BATTLE OF MARATHON: DARIUS, PHEIDIPPIDES, FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

XERXES’ MARCH TO GREECE BEFORE AND THE BATTLE OF THERMOPYLAE factsanddetails.com

BATTLE OF THERMOPYLAE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Greco-Persian Wars” by Peter Green (1998) Amazon.com;

“Persian Fire” by Tom Holland (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Greek and Persian Wars 499-386 BC” by Philip de Souza and Robert O'Neill (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Great Persian War” by George Beardoe Grundy (1861-1948) Amazon.com;

“Greek Hoplite Vs Persian Warrior: 499–479 BC” by Chris MacNab (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved Democracy” by Stephen P. Kershaw (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Persian Wars” by Herodotus Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Herodotus “ edited by Robert B. Strassler (Pantheon, 2008), richly illustrated and filled with accounts by experts but the translation leaves much to be desired. Amazon.com

“Marathon: How One Battle Changed Western Civilization” by Richard A. Billows (2010) Amazon.com;

“Thermopylae: The Battle That Changed the World” by Paul Cartledge (2007)

Amazon.com;

“The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter that Saved Greece -- and Western Civilization” by Barry Strauss (2005) Amazon.com;

“Salamis 480 BC: the Naval Campaign That Saved Greece” by William Shepherd and Peter Dennis (2010) Amazon.com;

“Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity” by Margaret C. Miller (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece” by Josiah Ober (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Greek World, 479-323 BC” by Simon Hornblower (1983) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in the Classical World” by John Warry, illustrated (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Wars of the Ancient Greeks” by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“War and Violence in Ancient Greece” by Hans van Wees Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Michael M. Sage (1996) Amazon.com;

Greeks Not Totally United In Their Coalition Against Persia

J. Wisniewski wrote in Listverse: If you haven’t seen 300: Rise of An Empire, much of the film’s suspense revolves around whether the multifarious Greek city-states will band together and fight off the Persian invasion. A Greek alliance did ward off the second Persian invasion, and Sparta was very suspicious of Athenian motives. That concludes the documentary portion of 300: Rise of An Empire.Many Greeks, chief among them the Athenians, weren’t satisfied with just sending Xerxes back to Persia. [Source J. Wisniewski, Listverse, July 21, 2014]

So an alliance stayed intact after the Second Persian Invasion under the guise of liberating the Greeks of Ionia (modern-day Turkey). This alliance became known as the Delian League, although perhaps “alliance,” is the wrong word. Working with Athens to fight the Persians was a matter of choosing one of two evils.Joining the confederacy led by Athens was like joining the mafia: You were in for life. Freedom-loving, democratic Athens ensured cooperation by conquering the cities that tried to leave its coalition.

City-states that refused alliance altogether fared even worse. One, the island of Melos, refused, and Athens blockaded it, starved the inhabitants, and then enslaved the surviving women and children. The League’s supposedly shared treasury? Athens eventually just requisitioned that.The rule of Athens became so intolerable that many city-states joined Sparta in a series of wars against the Athens-led Delian League, devastating the Greek peninsula for the better part of three decades. The Peloponnesian Wars only ended when Sparta allied itself with Persia.

Herodotus’s History and the Persian Wars

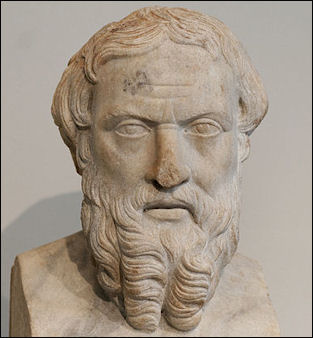

Herodotos Herodotus wrote “Histories” , a nine-volume account of Persian wars between 490 to 479 B.C. Sometimes called “The Persian Wars” or “History”, the work contains frequent and lengthy digressions and seems to leave no detail unturned. Herodotus’s style was lucid but poetic. Some regard him as the first master of prose. Cicero asked “what was sweeter than Herodotus.” A 20th century translator said, “Herodotus’s prose has the flexibility, ease and grace of a man superbly talking.”

Herodotus called his book “Historie” . In his time the word meant “research” or “inquiry” and has come to mean “history” in our sense of the world because of him. The book was so full of details and curious facts it is sometimes considered the first tourist guides and in fact was still the standard travel guide in the 19th century.

Herodotus observed a variety of local customs and concluded that men were servants to customs to which they were born. He noted that when Darius offered to pay his Greek subjects to eat the bodies of their fathers instead of burning them as was their custom, they refused no matter how much was offered them. He then offered to give money to Indians, who customarily ate the bodies of their deceased fathers, if they would burn their bodies. They also refused no matter how much was offered them. On the Egyptians he reported "In any home where a cat dies" the residents "shave off their eyebrows" and “sons never take care of their parents if they don’t want to, but daughters must whether they like it or not." He also noted “Women urinate standing up, men sitting down.”

His accounts of the natural world are no less entertaining. In the case of vipers and snakes he said the male is killed by the female during copulation but the male is “avenged” by their young who kill the female. In Book 3 he describes how Indian gold is produced by a species of ants—“huge ants, smaller than dogs but larger than foxes.”

The Persian Wars take up about a third of “History” — from the middle of Book 5 to the end of Book 9. The first four and half books proceed at a leisurely pace, with a lot of digressions, explaining the rise of the Persian Empire and tells readers everything they would ever want to know about Persia. See Persians Wars, History

Herodotus begins “Histories” with his account if Croesus and calls him “the first barbarian known who subjugated and demanded tribute from Hellenes.” The tale offers an introduction to a theme that would pervade the nine volumes of “Histories” — don’t overstep your bounds. Blinded by his success Croesus arrogantly misinterpreted a pronouncement by the Oracle of Delphi: “If you attack Persia you will destroy a great empire.” Croesus thought the oracle was referring to the Persians but she was in fact referring to his own. Sardis was sacked by the Persians. According to Herodotus, Croesus asked Cyrus, “What is it that all these men of yours are so intent upon doing.” Cyrus replied: “They are plundering your city and carrying off your treasures.” Croesus then corrected him: “Not my city or my treasures. Nothing there any longer belongs to me. It is you they are robbing.”

Herodotus

Herodotus (484?-425? B.C.) has been called the Father of History, a compliment initially given to him Cicero. He is given credit for recording information from all over but criticized for using less than reliable sources and sometimes espousing what seems like propaganda. Most of Herodotus's histories were stories he picked up from travelers, merchants and priests. He seems to have known many were exaggerations or unproven claims and he made some effort to pick out what was plausible. Occasionally he ascribed events to myths. Aristotle called him a “legend monger.” [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, April 28, 2008]

Daniel Mendelsohn wrote in The New Yorker, “Herodotus may not always give us the facts, but he unfailingly supplies something that is just as important in the study if what he calls “ta genomena ex” anthrupon” or “things that result from human action”: he give us the truth about the way things tend to work as whole, in history, civics, personality, and, of course, psychology.”

Herodotus was born in Halicarnassus, a town in Asia Minor that was home to one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, which was finished decades after he left. Halicarnassus was also regarded as a major intellectual center for a time. Herodotus spent some time in Athens and was a friend of Sophocles. He traveled widely and wrote extensively about the places he visited and people and places he heard about. He visited Egypt, southern Italy, Mesopotamia, Persian, the Levent and the Black Sea area. He wrote about the Scythians based on things he heard and pieced together the Persian Wars from oral traditions and things he observed.∞

Book: “Herodotus” by James Romm is a “lively short study.” “The Way of Herodotus” by Justin Marozzi (De Capo 2009) is an excellent travelog and encounter with Herodotus. “The Landmark Herodotus “ edited by Robert B. Strassler (Pantheon, 2008) is richly illustrated and filled with accounts by experts on everything from designs of ships to ancient measurements but the translation leaves much to be desired. The 1858 translation of “Histories” by George Rawlinson (Everyman Library) captures the “rich Homeric flavor and dense syntax” according to The New Yorker. The 1998 translation of Robin Waterfield (Oxford World Classic) is not bad.

Trouble in the Persian Provinces

The Persians had to deal with periodic rebellions in various parts of the empire. Egypt won independence from Persia only to be conquered again 60 years later. The second occupation lasted a little more than a decade before Alexander the Great arrived on the scene. The fall of Croesus in 547 B.C. marked the beginning of the incorporation of the Ionian Greeks of Asia Minor into the Persian Empire. Some of the Ionian states had appealed to Athens and Sparta for help. Athens later responded .

Croesus (561-547 B.C.) was the greatest and last the last king of Lydia. He captured the major Greek cities of western Asia Minor (Turkey) and then was defeated by Cyrus the Great of Persia. He is said to have produced a lavish palace in his capital of Sardis and was regarded by some as one of the richest men that ever lived. The Lydians became so wealthy under Croesus the expression “rich as Croesus” became popular in antiquity. He was the first ruler to produce gold coins (before that they were made from the silver-alloy electrum) and certify the weight of gold in coins.

Ionian Revolt Campaign Map

Herodotus begins “Histories” with his account if Croesus and calls him “the first barbarian known who subjugated and demanded tribute from Hellenes.” The tale offers an introduction to a theme that would pervade the nine volumes of “Histories” — don’t overstep your bounds. Blinded by his success Croesus arrogantly misinterpreted a pronouncement by the Oracle of Delphi: “If you attack Persia you will destroy a great empire.” Croesus thought the oracle was referring to the Persians but she was in fact referring to his own. Sardis was sacked by the Persians. According to Herodotus, Croesus asked Cyrus, “What is it that all these men of yours are so intent upon doing.” Cyrus replied: “They are plundering your city and carrying off your treasures.” Croesus then corrected him: “Not my city or my treasures. Nothing there any longer belongs to me. It is you they are robbing.”

Half a century later, starting in 499 B.C. Ionian Greek states began rebelling against their Persian overlords, leading to the Persian invasion of Greece. In 499 B.C., Ionian Greeks in Asia Minor rebelled against their Persian lords. Athens and Eretria supported the rebellions and Greeks sacked the important Persian city of Sardis. The Persians retaliated by destroying the Greek city of Miletos. This set the state stage for the Persian Wars.

Darius developed a plan to invade Greece and teach the Athenians a lesson they wouldn’t forget. The gods favored the Greeks during Darius’s first invasion. A fleet of 600 Persian ships crossed the Dardanelles and then was ravaged by storm off of Mount Anthos that destroyed half the fleet.

Battle of Marathon

In 490 B.C., Darius sent a fleet of 600 ships across the Aegean Sea and landed with a force of 20,000 men on the Plains of Marathon, about 25 miles from Athens. The resulting Battle of Marathon is one the most famous battles in ancient Greek history. The Athenian army, under the command of general Miltaides, was outnumbered six to one. The Athenian army consisted of about 10,000 Athenians, aided by 1,000 Plataeans, and included many aristocrats. The strength of the Persian Army was its archers.

Marathon, the mound of the Plataeans Miltaides organized his forces so that its strength was in the wings. He ordered a small central force to advance. As expected they were pushed back. When the Persians let down their guard momentarily to water their horses. Miltaides ordered the Athenian wings to attack on a full run. Before the Persian archers had time to string their bows the Athenians charged them like madmen and fought them at close range, where the Persian bows and arrows were ineffective and where the Athenians, with their protective armor and deadly spears were able to sow maximum terror among the Persians while sustaining only minor casualties themselves.

The panic-stricken Persians retreated to their boats. Aeschylus later wrote that his brother was killed when his arm was cut off as he tried to stop a Persian ship from retreating. After Athens’ victory Pheidippides reportedly ran 26.3 miles from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory of the Greeks over the Persians and then fell dead after he gave the message: Rejoice! We conquer!" See Marathon, Sports, Greeks

But Darius had not given up yet and during the night he steered his boats to what he thought was an unguarded Athens. But Miltiades, who had marched his army 26 miles during the night to Athens, was waiting for the Persians on high ground and the Persians were routed again. According to Herodotus, 6,400 Persians were killed, while only 192 Athenians and 11 Plateans died. Breaking their tradition of carrying their dead back to their cities, the Greeks instead buried them in the battlefield and a erected grave mounds that are still visible today.

Darius return to Persia with a third of his army gone.. After the victory many Greek states united to defend against another Persian attack, with Sparta dominating the land and Athens controlling the seas.

See Separate Article: BATTLE OF MARATHON: DARIUS, PHEIDIPPIDES, FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

Xerxes Advances on Greece

Ten years after the Battle of Marathon, in 480 B.C., the Greeks got their revenge in the Battle of Thermopylae. Darius's successor, King Xerxes, showed up on the shores of Greece, this time with a huge army and Carthage as an ally. According to tradition tat army numbered 1.7 million men. Herodotus put the figure at 2,317,610, which included infantry, marines and camel riders. Paul Cartledge, a professor at Cambridge University and author a book on the Spartans said the true figure is somewhere between 80,000 and 250,000.

Persian lion

The endeavor required digging channels across isthmuses and building bridges over large expanses of water. The huge army arrived on land this time, crossing the Dardanelles (in present-day Turkey) on a bridge of boats tied together with flax and papyrus. The first effort was swept away in a storm. Xerxes was reportedly so enraged that he ordered the engineers who built it beheaded. "I even heard," Herodotus wrote, "that Xerxes commanded his royal tattooers to tattoo the water!" He ordered the water to be given 300 lashes and threw in some shackles and denounced the waterway as “a turbid and briny river.” The bridge was rebuilt and the Persian army spent seven days crossing it.

Xerxes (ruled 486-465 B.C.) was the son of Darius. He was regarded as weak and tyrannical. He spent the early years of his reign putting down rebellions in Egypt and Babylon and preparing to launch another attack on Greece with a huge army that he assumed would easily overwhelm the Greeks. Herodotus characterizes Xerxes as man a layers of complexity. Yes he could be cruel and arrogant. But he could also be childishly petulant and become tear-eyed with sentimentality. In one episode, recounted by Herodotus, Xerxes looked over the mighty force he created to attack Greece and then broke down, telling his uncle Artabanus, who warned him not to attack Greece, “by pity as I considered the brevity of human life.”

See Separate Article: XERXES MARCH TO GREECE BEFORE AND THE BATTLE OF THERMOPYLAE europe.factsanddetails.com

Battle of Thermopylae

Most city states made peace with Xerxes but Athens and Sparta didn't. In 480 B.C. a force of only 7,000 Greeks met the huge Persian force at Thermopylae, a narrow mountain pass who name means “the hot gates,” which guarded the way to central Greece. Lead by a group of 300 Spartan warriors the Greeks held off the Persian for four days. The Persian threw their crack units at the Greeks but each time Greek "hoplite" tactics and Spartan spears inflicted a large number a casualties.

The 300 Spartan warriors were portrayed in the film “300" as a bunch of fearless, muscle-bound lunatics. When warned that so many arrows will be fired by Persian archer the arrows will “blot out the sun,” one Spartan soldier retorted. “Then we will fight in the shade.” (“In the shade” is the motto of the an armored division in the present-day Greek army).

The Persians eventually found a lightly guarded trail, with the help of a traitorous Greek. The Spartans fought the Persians again. Only two of the 300 Spartans survived. According to Cambridge University professor Paul Cartledge in his book “The Spartans” one was so humiliated he committed suicide out of shame on their return to Sparta. The other redeemed himself by getting killed in another battle.

By holding on for so long against such incredible odds the Spartans allowed the Greeks to regroup and make a stand in the south and inspired the rest of Greece to pull together and mount an effective defense against the Persians. The Persians then moved on to southern Greece. The Athenians left their city en masse and let the Persians burn it the ground with flaming arrows so they could return and fight another day. The Russians employed a similar strategy against Napoleon.

See Separate Article: BATTLE OF THERMOPYLAE europe.factsanddetails.com

Thermopylae

Battle of Salamis

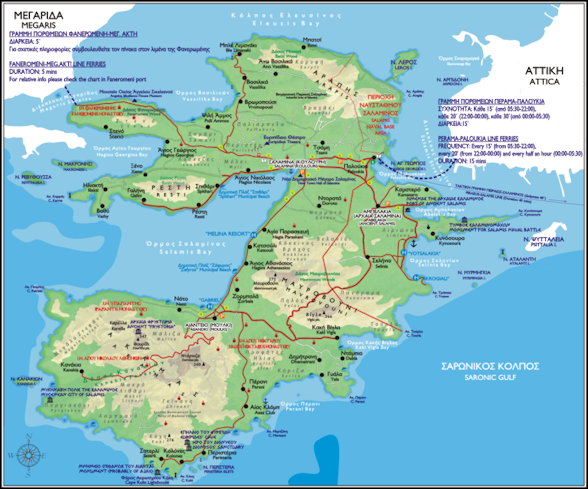

While the Spartans were holding off the Persians, the citizens of Athens were transported by ship to a nearby island of Salamis, where Athens tricked Persia into fight a sea battle, the Battle of Salamis.

The Battle of Salamis defeat of Persian invasion in 480 B.C. is one of the most important events in world history. It took place near the island of Salamis and the promontory of Cynosura. Hundreds of crowded ships participated. Greek trireme aimed to maneuver to ram Persian ships on their starboard (right) sides, destroying many of the oars in the collision. The Persians fought back with arrows and javelins launched from the decks of their ships. [Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

The idea of a sea battle was still a novel idea at that time. The Persian fleet outnumbered the Athenian fleet three to one. The Greeks, using light oared ships with battering rams on their bows, held the position and waited patiently as the heavy Persian ships approached one at a time and got trapped in constricted waters at a narrow passage, where the lighter Greek ships rowed out in circular formation and rammed their prows into Persian ships, which sunk. About a third of the 700 Persian ships were lost but only 40 of the 500 Athenian ships were lost.

"Ship dashed her brazen beak against ship...the sea was no longer to behold, filled as it was, with wrecks and the slaughter of men," the playwright Aeschylus wrote." Xerxes watched from a mountaintop and "shrieked aloud" as his soldiers were defeated in hand to hand combat at sea. In the Aeschylus play “The Persians”, written eight years after the Battle of Salamis, Xerxes becomes the quintessence of a despot in defeat, even evoking pity and sympathy, “Here am I, alas, O woe: / To may my native an ancestral and ./ Woe is the evil I’ve become.”

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK NAVY: FIGHTING TRIREMS, OARSMEN AND SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com

Heroes of the Battle of Salamis

Arturo Sánchez Sanz wrote in National Geographic: Naval battles not only happened above water; they could also be fought under the sea. From the ninth century B.C., Greek navies were hiring divers who were capable of staying underwater for long periods of time, a feat similar to that undertaken by free divers today. Scyllias of Scione and his daughter Hydna were two such celebrated swimmers. [Source: Arturo Sánchez Sanz, National Geographic, February 24, 2023]

Accounts of their heroism during Xerxes I’s Persian invasion of Greece in 480 B.C. have been found in several accounts. Scyllias and Hydna are credited with scuttling the Persian vessels during this conflict. During a savage storm, they dove under the anchored Persian ships, cutting the ropes binding them to the anchors. The ships began to drift uncontrollably toward the storm and were destroyed.

Both Scyllias and Hydna were heroes to the victorious Greeks, who later dedicated statues to them at Delphi, the Greek world’s most sacred place. Writing in the late fifth century B.C., Greek historian Herodotus wrote a slightly different version. In his telling, Scyllias was a diver for Xerxes who defected to the Greek side, swimming some eight nautical miles (allegedly using a reed as a kind of snorkel) to reach the Greeks and inform them of weaknesses in the Persian navy. Greek forces capitalized on the information and soundly defeated the Persians .

Herodotus on Artemisia and the Battle of Salamis

Artemisia I of Caria was a Greek queen of the ancient Greek city-state of Halicarnassus and of the nearby islands of Kos, Nisyros and Kalymnos, within the Persian satrapy of Caria. She fought as an ally of Xerxes against the Greek city states during the second Persian invasion of Greece, personally commanded her contribution of five ships at the naval battles of Artemisium and Salamis in 480 B.C.. She is mostly known through the writings of Herodotus, himself a native of Halicarnassus, who praises her courage and the respect in which Xerxes held her. [Source: Wikipedia]

Herodotus wrote in Book VII of “Histories”: “Of the other lower officers I shall make no mention, since no necessity is laid on me; but I must speak of a certain leader named Artemisia, whose participation in the attack upon Hellas, notwithstanding that she was a woman, moves my special wonder. She had obtained the sovereign power after the death of her husband; and, though she had now a son grown up, yet her brave spirit and manly daring sent her forth to the war, when no need required her to adventure. Her name, as I said, was Artemisia, and she was the daughter of Lygdamis; by race she was on his side a Halicarnassian, though by her mother a Cretan. She ruled over the Halicarnassians, the men of Cos, of Nisyrus, and of Calydna; and the five triremes which she furnished to the Persians were, next to the Sidonian, the most famous ships in the fleet. She likewise gave to Xerxes sounder counsel than any of his other allies. Now the cities over which I have mentioned that she bore sway were one and all Dorian; for the Halicarnassians were colonists from Troizen, while the remainder were from Epidauros. Thus much concerning the sea-force.” [Source: Herodotus “The History of Herodotus” Book VII and VIII on the Persian War, 440 B.C., translated by George Rawlinson, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

Battle of Salamis

In Book VIII, he wrote: “Mardonius accordingly went round the entire assemblage, beginning with the Sidonian monarch, and asked this question; to which all gave the same answer, advising to engage the Hellenes, except only Artemisia, who spoke as follows: "Say to the king, Mardonius, that these are my words to him: I was not the least brave of those who fought at Euboia, nor were my achievements there among the meanest; it is my right, therefore, O my lord, to tell you plainly what I think to be most for your advantage now. This then is my advice:

“"Spare your ships, and do not risk a battle; for these people are as much superior to your people in seamanship, as men to women. What so great need is there for you to incur hazard at sea? Are you not master of Athens, for which you did undertake your expedition? Is not Hellas subject to you? Not a soul now resists your advance. They who once resisted, were handled even as they deserved. Now learn how I expect that affairs will go with your adversaries. If you are not over-hasty to engage with them by sea, but will keep your fleet near the land, then whether you stay as you are, or march forward towards the Peloponnesos, you will easily accomplish all for which you are come here.

"The Hellenes cannot hold out against you very long; you will soon part them asunder, and scatter them to their several homes. In the island where they lie, I hear they have no food in store; nor is it likely, if your land force begins its march towards the Peloponnesos, that they will remain quietly where they are — at least such as come from that region. Of a surety they will not greatly trouble themselves to give battle on behalf of the Athenians. On the other hand, if you are hasty to fight, I tremble lest the defeat of your sea force bring harm likewise to your land army. This, too, you should remember, O king; good masters are apt to have bad servants, and bad masters good ones. Now, as you are the best of men, your servants must needs be a sorry set. These Egyptians, Cyprians, Cilicians, and Pamphylians, who are counted in the number of your subject-allies, of how little service are they to you!"

“VIII.69: As Artemisia spoke, they who wished her well were greatly troubled concerning her words, thinking that she would suffer some hurt at the king's hands, because she exhorted him not to risk a battle; they, on the other hand, who disliked and envied her, favored as she was by the king above all the rest of the allies, rejoiced at her declaration, expecting that her life would be the forfeit. But Xerxes, when the words of the several speakers were reported to him, was pleased beyond all others with the reply of Artemisia; and whereas, even before this, he had always esteemed her much, he now praised her more than ever. Nevertheless, he gave orders that the advice of the greater number should be followed; for he thought that at Euboia the fleet had not done its best, because he himself was not there to see — whereas this time he resolved that he would be an eye-witness of the combat.

“VIII.87: What part the several nations, whether Hellene or barbarian, took in the combat, I am not able to say for certain; Artemisia, however, I know, distinguished herself in such a way as raised her even higher than she stood before in the esteem of the king. For after confusion had spread throughout the whole of the king's fleet, and her ship was closely pursued by an Athenian trireme, she, having no way to fly, since in front of her were a number of friendly vessels, and she was nearest of all the Persians to the enemy, resolved on a measure which in fact proved her safety. Pressed by the Athenian pursuer, she bore straight against one of the ships of her own party, a Calyndian, which had Damasiyourmus, the Calyndian king, himself on board. I cannot say whether she had had any quarrel with the man while the fleet was at the Hellespont, or no — neither can I decide whether she of set purpose attacked his vessel, or whether it merely chanced that the Calyndian ship came in her way — but certain it is that she bore down upon his vessel and sank it, and that thereby she had the good fortune to procure herself a double advantage. For the commander of the Athenian trireme, when he saw her bear down on one of the enemy's fleet, thought immediately that her vessel was a Hellene, or else had deserted from the Persians, and was now fighting on the Hellene side; he therefore gave up the chase, and turned away to attack others.

“VIII.88: Thus in the first place she saved her life by the action, and was enabled to get clear off from the battle; while further, it fell out that in the very act of doing the king an injury she raised herself to a greater height than ever in his esteem. For as Xerxes beheld the fight, he remarked (it is said) the destruction of the vessel, whereupon the bystanders observed to him — "See, master, how well Artemisia fights, and how she has just sunk a ship of the enemy?" Then Xerxes asked if it were really Artemisia's doing; and they answered, "Certainly; for they knew her ensign" — while all made sure that the sunken vessel belonged to the opposite side. Everything, it is said, conspired to prosper the queen — it was especially fortunate for her that not one of those on board the Calyndian ship survived to become her accuser. Xerxes, they say, in reply to the remarks made to him, observed: "My men have behaved like women, my women like men!"

Legacy of the Persian Wars

After Salamis and Greek victories at Plataea (479 B.C.) and another sea battle at Mycale (479 B.C.), the Greeks were able to defy impossible odds and drive the Persians back into Asia. At the Battle of Cunaxa, in 401 B.C., the Greeks slaughtered the Persians without suffering a single fatality. The Greek victories was improbable, even miraculous. Persia was the greatest military power in the world. The Greeks were a bunch of upstarts. Carol Alexander wrote in National Geographic that it was like "if the United States had been routed by a Caribbean coalition."

These victories gave the Greeks a sense of invisibility and set up the Golden Age of Athens. Some historians view the Persian Wars as one the most important series of battles in the history of the world, because without them democracy would have never have been able to take root. If the outcome of these wars had been different and Persia had prevailed the world would be a very different place today.

The Persian Wars were the first time the Greek city states, which often fought among themselves, banded together to defeat a common enemy. A sense of common Greekhood developed. For a while a kind of United States of Greece was created with a capital on Olympia. where a board was set up to settle disputes. The board only lasted for about a decade before the city states were feuding among themselves once again.

Herodotus doesn’t offer much in the way of explanation for why it all happened in terms of politics — or which system was best: monarchy, oligarchy and democracy. He criticized them all and remained rather neutral and detached. In the end he chalks up Persia’s defeat to the corruption of power and overreaching oneself.

Salamina Map

Decline of Persia After the Persian Wars and Darius III

The defeat of the Persians at Salamis highlighted the weaknesses of the Persians and is regarded as the beginning of the decline of the Persian Empire.

The last 125 years of Persian rule was marked by conspiracies, intrigues, assassinations and revolts by subjects straining under high taxes. The empire was briefly solidified under brutal Artaxerxes III (ruled 362-338) who killed all of his relatives and was himself poisoned by his physicians. His successor was poisoned two years after he took the throne. The mad Persian King Cambyses II saw his vast army was swallowed up by the Sea of Sand.

Darius III was leader of Persia at the time of Alexander the Great. He was regarded as weak and cowardly and he demonstrated these shortcomings in his confrontation with Alexander. His death and defeat marks the fall of the Persian Empire and the end of the Achaemenid dynasty.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024