Home | Category: Greek Classical Age (500 B.C. to 323 B.C.) / Military

PELOPONNESIAN WAR

Destruction of the Athenian army at Syracuse

Throughout the 5th century B.C., particularly between 460 and 445 B.C., alliances led by Athens and Sparta fought one another for control of Greece. The historian and general Thucydides attributed the trouble to "greed and ambition" and wrote "practically the whole Hellenic world was convulsed.” In Sparta, an earthquake in 464 B.C. destroyed the city-state and provoked an uprising.

The 27-year Peloponnesian War (431 B.C. to 404 B.C.) is named after the Peloponnesian League, an alliance led by Sparta that included Corinth and Thebes, that dominated the Peloponnesian peninsula . Sparta had traditionally been stronger militarily than Athens but Athens was stronger and richer as a result of tributes pouring in through the Delian League — an alliance that stretched across the Mediterranean. The resulting imbalance had much to do with the why the war was fought.

The Peloponnesian War was one of the of bloodiest and cruelest wars in ancient history. Greeks for Athens and Sparta committed horrible atrocities against one another and refused to tolerate neutrality by the other Greek city states. Children were murdered in their classrooms by mercenaries; civilians were murdered and enslaved en masse; worshippers were burned at the altar where the prayed and the dead were left to rot in the battlefields.

The Peloponnesian War has been compared to the Cold War, with some history saying it serves as a parable to what might have happened if things got out of hand between the United States (Athens) and the Soviet Union (Sparta). In February 1947, after World War II and as the Cold War was getting started, U.S. President Truman’s said during a speech at Princeton University, “I doubt seriously whether a man can think with full wisdom and with deep convictions regarding some of the basic international issues today who has not at least reviewed in his mind the period of the Peloponnesian War and the Fall of Athens.”

Websites on Ancient Greece: The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) and After, See Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University sourcebooks.web.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu;

RELATED ARTICLES:

THUCYDIDES europe.factsanddetails.com

MAJOR EVENTS DURING THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MITYLENIAN DEBATE AND MELIAN DIALOGUE: PUNISHMENT, COMPASSION, POLITICAL REALISM DURING THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR;

END OF CLASSICAL GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Peloponnesian War” by Donald Kagan (2003) Amazon.com;

“A War Like No Other” by Victor Davis Hanson (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece” by Jennifer Roberts (2017) Amazon.com;

“History of the Peloponnesian War” by Thucydides (1834) Amazon.com;

“Thucydides, The Reinvention of History” by Donald Kagan, (Viking, 2009) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Thucydides” Amazon.com;

“Athens and Sparta: Constructing Greek Political and Social History from 478 BC” by Anton Powell (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Spartan Army” by John Lazenby (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Spartan Army” by Nicholas Sekunda (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Athens: The Story of the World's Greatest Civilization” by Anthony Everitt (2016) Amazon.com;

“Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy” by John R. Hale (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Athens” by Plutarch (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Athenian Empire” by Russell Meiggs (1972) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece” by Josiah Ober (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Greek World, 479-323 BC” by Simon Hornblower (1983) Amazon.com;

“A Chronology of Ancient Greece” by Timothy Venning (2015) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in the Classical World” by John Warry, illustrated (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Wars of the Ancient Greeks” by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“War and Violence in Ancient Greece” by Hans van Wees Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Michael M. Sage (1996) Amazon.com;

Donald Kagan is a professor of classics and history at Yale known for conservative political views. Victor Davis Hanson is another expert of the Peloponnesian War at the California State University, Fresno. Dick Cheney described him as his favorite historians and the person who summed up his own philosophy best (One of the lessons of the Peloponnesian War Hanson wrote was that “resolute action” brings “lasting peace”).

Peloponnese League

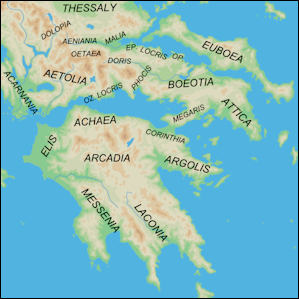

regions of southern Greece and the Peloponnese The Peloponnesian League was a Sparta-dominated alliance in the Peloponnesus that existed from the 6th to the 4th centuries B.C.. It is known mainly for being one of the two rivals in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), against the Delian League, which was dominated by Athens. [Source: Wikipedia +]

By the end of the 7th century BC Sparta had become the most powerful city-state in the Peloponnese and was the political and military hegemon over Argos, the next most powerful city-state. Sparta acquired two powerful allies, Corinth and Elis (also city-states), by ridding Corinth of tyranny, and helping Elis secure control of the Olympic Games. Sparta continued to aggressively use a combination of foreign policy and military intervention to gain other allies. Sparta suffered an embarrassing loss to Tegea in a frontier war and eventually offered them a permanent defensive alliance; this was the turning point for Spartan foreign policy. Many other states in the central and provincial northern Peloponnese joined the league, which eventually included all Peloponnesian states except Argos and Achaea. +

The Peloponnesian League was organized with Sparta as the hegemon, and was controlled by the council of allies which was composed of two bodies: the assembly of Spartans and the Congress of Allies. Each allied state had one vote in the Congress, regardless of that state's size or geopolitical power. No tribute was paid except in times of war, when one third of the military of a state could be requested. Only Sparta could call a Congress of the League. All alliances were made with Sparta only, so if they so wished, member states had to form separate alliances with each other. And although each state had one vote, League resolutions were not binding on Sparta. Thus, the Peloponnesian League was not an "alliance" in the strictest sense of the word (nor was it wholly Peloponnesian for the entirety of its existence). The league provided protection and security to its members. It was a conservative alliance which supported Oligarchies and opposed tyrannies and democracies. +

Delian League tributes

After the Persian Wars the League was expanded into the Hellenic League and included Athens and other states. The Hellenic League was led by Pausanias and, after he was recalled, by Cimon of Athens. Sparta withdrew from the Hellenic League, reforming the Peloponnesian League with its original allies. The Hellenic League then turned into the Athenian-led Delian League. This might have been caused by Sparta and its allies' unease over Athenian efforts to increase their power. The two Leagues eventually came into conflict with each other in the Peloponnesian War. +

Delian League

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: The "Delian League, or Confederacy of Delos is “the name given to a confederation of Greek states under the leadership of Athens, with its headquarters at Delos, founded in 478 B.C. shortly after the final repulse of the expedition of the Persians under Xerxes I. This confederacy, which after many modifications and vicissitudes was finally broken up by the capture of Athens by Sparta in 404, was revived in 378-7 (the "Second Athenian Confederacy") as a protection against Spartan aggression, and lasted, at least formally, until the victory of Philip II of Macedon at Chaeronea. These two confederations have an interest quite out of proportion to the significance of the detailed events which form their history. They are the first two examples of which we have detailed knowledge of a serious attempt at united action on the part of a large number of selfgoverning states at a relatively high level of conscious political development. The first league, moreover, in its later period affords the first example in recorded history of selfconscious imperialism in which the subordinate units enjoyed a specified lo~cal autonomy with an organized system, financial, military and juaicial. The second league is further interesting as the precursor of the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues.[Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Several causes contributed to the formation of the first Confederacy of Delos. During the 6th century B.C. Sparta had come to be regarded as the chief power, not only in the Peloponnese, but also in Greece as a whole, including the islands of the Aegean. The Persian invasions of Darius and Xerxes, with the consequent importance of maritime strength and the capacity for distant enterprise, as compared with that of purely military superiority in the Greek peninsula, caused a considerable loss of prestige which Sparta was unwilling to recognize. Moreover, it chanced that at the time the Spartan leaders were not men of strong character or general ability... the inelastic quality of the Spartan system was unable to adapt itself to the spirit of the new age. To Aristides was mainly due the organization of the new leavue and the adiustment of the contributions of the various allies in ships or in money. His assessment, of the details of which we know nothing, was so fair that it remained popular long after the league of autonomous allies had become an Athenian empire. The general affairs of the league were managed by a synod which met periodically in the temple of Apollo and Artemis at Delos, the ancient centre sanctified by the common worship of the Ionians. In this synod the allies met on an equality under the presidency of Athens.

“The league was, therefore, specifically a free confederation of autonomous Ionian cities founded as a protection against the common danger which threatened the Aegean basin, and led by Athens in virtue of her predominant naval power as exhibited in the wae against Xerxes. Its organization, adopted by the common synod, was the product of the new democratic ideal embodied in the Cleisthenic reforms, as interpreted by a jurt and moderate exponent. It is one of the few examples of free corporate action on the part of the ancient Greek cities, whose centrifugal yearning for independence so often proved fatal to the Hellenic world.

“Naturally came to pass that certain of the allies became weary of incessant warfare and looked for a period of commercial prosperity. Athens, as the chosen leader, and supported no doubt by the synod, enforced the contributions of ships and money according to the assessment. Gradually the allies began to weary of personal service and persuaded the synod to accept a money commutation. The result was, however, extremely bad for the allies, whose status in the league necessarily became lower in relation to that of Athens, while at the same time theil military and naval resources correspondingly diminished. Athens became more and more powerful, and could afford to disregard the authority of the synod. Another new feature appeared in the employment of coercion against cities which desired to secede. Athens might fairly insist that the protection of the Aegean would become impossible if some of the chief islands were liable to be used as piratical strcngholds, and further that it was only right that all should contribute in some way to the security which all enjoyed The result was that, in the cases of Naxos and Thasos, for instance, the league's resources were employed not against the Persians but against recalcitrant Greek islands, and that the Greek ideal of separate autonomy was outraged. Sparta had so far no quarrel with Athens. Athens thus became mistress of the Aegean, while the synod at Delos had become practically, if not theoretically, powerless.” After this the Delian League for all intents and purposes the Athenian Empire. As friction between Sparta and Athens grew, the result was the Peloponnesian War.

Delos

Delos is a small (350.64 hectares), rocky island in the centre of the Aegean Sea in the Cyclades archipelago. Considered “the most sacred of all islands” (Callimachus, 3rd century B.C.) in ancient Greek culture, it was where, the Greek legend goes, Apollo-Sun, god of daylight, and his twin sister Artemis-Moon, goddess of night light, were born. According to UNESCO: “Apollo's sanctuary attracted pilgrims from all over Greece and Delos was a prosperous trading port. The island bears traces of the succeeding civilizations in the Aegean world, from the 3rd millennium B.C. to the palaeochristian era. The archaeological site is exceptionally extensive and rich and conveys the image of a great cosmopolitan Mediterranean port. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“The island was first settled in the third millennium B.C. . The Apollonian sanctuary, established at least since the 9th century B.C. reached the peak of its glory during the Archaic and Classical period, when it acquired its Pan-Hellenic character. After 167 B.C. as a result of the declaration of Delos as a free port, all the commercial activity of the eastern Mediterranean was concentrated on the isle. Rich merchants, bankers and ship-owners from all over the world settled there, attracting many builders, artists and craftsmen, who built for them luxurious houses, richly decorated with frescoes and mosaic floors.

The island of Delos bears unique witness to the civilizations of the Aegean world since the 3rd millennium B.C.. From the 7th century B.C. to the pillage by Athenodoros in 69 B.C. the island of Delos was one of the principal Pan-Hellenic sanctuaries. The feast of the Delians, which was celebrated every four years in the month of May until 316 B.C. included gymnastic, equestrian and musical competitions, Archaic Age dances, theatrical productions and banquets. Like the Olympic and the Pythic Games, it was one of the major events in the Greek world. =

“Delos is directly and tangibly associated with one of the principal myths of Hellenic civilisation. It was on this arid islet that Leto, made pregnant by Zeus and fleeing the vengeance of Hera, gave birth to Apollo and Artemis after a difficult labour. According to a Homeric hymn, the island, which until then had been floating, became anchored to the floor of the ocean. The newborn Phoebus- Apollo threw off his swaddling clothes bathed the universe in light and began walking with his cither and his bow. Kynthos, the mountain of Zeus, and the wheel-shaped lake, close to which the pregnant Leto suffered labor pains for nine days and nights, remain essential landmarks of the island's sacred geography, which was clearly defined by the additions made to the Delian sanctuary to Apollo between the 6th and the 1st centuries B.C.” =

Greece on the Eve of the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War was the culmination of 40 years of simmering tensions between the era’s two great superpowers: free-wheeling, democratic Athens and Sparta, a militaristic oligarchy. Angry about trade restrictions and imperialism, and contemptuous of Athenian permissiveness and lack of discipline, Sparta declared war on Athens in 431 B.C. The war lasted for 27 years, drained both sides of resources, morale and energy.

The Peloponnesian League was fed up with Athens, its political subversion and commercial dominance and it viewed Athens as a threat. Some historians argue that the Peloponnesian War was the result of a break down of a balance of power between two adversaries — Athens and Sparta — and the swift, expansion of one side — Athens.

Both sides championed the war as one of liberation with each side claiming too free a bullied ally. The war began with a relatively small dispute over Corinth, a Spartan ally, and some minor fighting in a town near Athens and escalated into a conflict that years, involved numerous states, and ended with the demise of Athens and the abolition of its democratic institutions.

Pericles, the Delian League and Events Before the Peloponnes War

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: Pericles' policy towards the members of the Delian League transformed them from allies into subjects, A conflict between Corcyra and Corinth, the second and third naval powers of Greece, led to the simultaneous appearance in Athens of an embassy from either combatant (433). Pericles had, as it seems, resumed of late a plan of Western expansion by forming alliances with Rhegium and Leontini, and the favourable position of Corcyra on the trade-route to Sicily and Italy, as well as its powerful fleet, no doubt helped to induce him to secure an alliance with that island, and so to commit an unfriendly act towards a leading representative of the Peloponnesian League. Pericles now seemed to have made up his mind that war with Sparta, the head of that League, had become inevitable. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“In the following spring he fastened a quarrel upon Potidaea, a town in Chalcidice, which was attached by ancient bonds to Corinth, and in the campaign which followed Athenian and Corinthian troops came to blows. A further casus belli was provided by a decree forbidding the importation of Megarian goods into the Athenian Empire, presumably in order to punish Megara for her alliance with Corinth (spring 432 B.C.). The combined complaints of the injured parties led Sparta to summon a Peloponnesian congress which decided on war against Athens, failing a concession to Megara and, Corinth (autumn 432 B.C.). In this crisis Pericles persuaded the wavering assembly that compromise was useless, because Sparta was resolved to precipitate a war in any case.

It was at this time that Cimon, who had striven to maintain a balance between Sparta, the chief military, and Athens, the chief naval power, was successfully attacked by Ephialtes and Pericles. During the ensuing years, apart from a brief return to the Cimonian policy, the resources of the Delian League, or, as it has now become, the Athenian empire, were directed not so much against Persia as against Sparta, Corinth, Aegina and Boeotia.

“The next important event is the revolt of Samos, which had quarreled with Miletus over the city of Priene. The Samians refused the arbitration of Athens. The island was conquered with great difficulty by the whole force of the league, and from the fact that the tribute of the Thracian cities and those in Hellespontine district was increased between 439 and 436 B.C. we must probably infer that Athens had to deal with a widespread feeling of discontent about this period. It is, however, equally noticeable on the one hand that the main body of the allies was not affected, and on the other that the Peloponnesian League on the advice of Corinth officially recognized the right of Athens to deal with her rebellious subject allies, and refused to give help to the Samians.

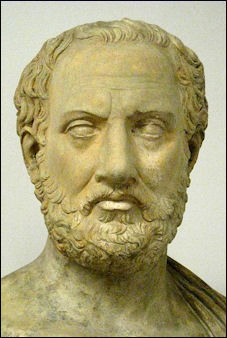

Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War

Thucydides (471?-400? B.C.) wrote extensively about events in Greece and told the story of the draining, disastrous 30-year Peloponnesian War that destroyed Athens when it was in its prime in “History of the Peloponnesian War”. Little known about his life other than that he was an soldier and an officer. One of the few times he talks about himself is when he mentions he survived the plague. [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, January 12, 2004]

Thucydides (471?-400? B.C.) wrote extensively about events in Greece and told the story of the draining, disastrous 30-year Peloponnesian War that destroyed Athens when it was in its prime in “History of the Peloponnesian War”. Little known about his life other than that he was an soldier and an officer. One of the few times he talks about himself is when he mentions he survived the plague. [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, January 12, 2004]

Tracy Lee Simmons wrote in the Washington Post: “One of the most eminently, and now, predictably, quotable figures of the classical world, Thucydides assuredly deserves his press. Few so well understood the machinations of he human heart and mind when facing the extremities of the human predicament — plague, betrayal, defeat, and the abject humiliation of war — and fewer still could distill the hard-won wisdom of experience into tight, shimmering phrases and radiant lapidary passages.”

Thucydides was a participant in the events he described. He caught the plague he detailed with such precision. He was also far from a distant observer of the Peloponnesian War: he was a general high in the Athenian command early in the war who was forced into exile after he failed to prevent the Spartans from capturing the northern city of Amphipolis in 422. He wrote his account years later in part to defend his actions and in the end puts the blame on the demise of Athens on democracy and its demagogue politicians while arguing it was enlightened military that almost saved the day.

Book: “Thucydides, The Reinvention of History” by Donald Kagan (Viking, 2009). Kagan is a professor of classics and history at Yale.

Thucydides’s “History of the Peloponnesian War” is the only extant eyewitness account of the first twenty year of the war. He said he began taking notes “at the very outbreak” of the conflict because he had hunch it would be — a great war and more worthy writing about than any of those which had taken place in the past.” His accounts end in mid sentence during the description of a naval battle in 411 but we can tell from other references in his work that he was around to see the war end in 404 B.C.

After the Peloponnesian War

The decline of Greek civilization and the end of the Golden Age of Athens began in 404 B.C. with Sparta's victory over Athens in the Great Peloponnesian War. Although democracy was reestablished in Athens in the 4th century B.C. and Plato founded of the Academy in 387 B.C. and Aristotle founded the Lyceum in 335 B.C., the war left Greece bitterly divided and open to conquest from Macedonia.

After Athens surrendered to Sparta, the Long Walls that surrounded Athens were torn down by the Spartans to music of flutes. Sparta installed despotic rulers but mercifully allowed Athens' people to live. Captured Athenian soldiers were put to work as slaves in Syracuse's stone quarries.

After the Peloponnesian Wars, Greek culture declined: ambition replaced honor, oratory skill became a method of furthering one’s career and attaining power, democratic institutions were undermined by corruption and citizens demanded “rights, not duties, and pleasure instead of work.”

Sparta remained the supreme power in Greece for about 30 years. Non-Spartan Greeks chafed under Spartan rule. There were rebellions and unrest and progressively fewer Spartan warrior to carry on the traditions. Finally when only a few hundred Spartan citizen-soldier remained the Thebans under Epaminodas defeated Sparta. Later it like the rest of Greece came under the control of Alexander the Great.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024