ANCIENT GREEK WEAPONS

Athenian hoplite

The ancient warrior’s weapons were the dagger, sword, spear, javelin, bow, and sling. A fully armed Homeric hero carried a shield, sword, and one or two spears. For the most part this was also the armor of the heavy-armed soldiers of the historic period; there were, however, a few modifications in the centuries which followed Homer. The main hoplite weapon was an eight- to ten-foot thrusting spear with an iron tip and butt.

Offensive arms could be divided into those which were used in close combat, especially lance and sword, and those which were used from a distance, in particular, javelin, bow, and sling. There were two other weapons for close encounter, the club and the battle-axe, but they are not important for Greek warfare. The former was chiefly used in the mythical contests of pre-historic times, the latter, represented on works of art as the usual weapon of the Amazons, is sometimes mentioned in Homer as used by Greek heroes, but it was afterwards only in use as an actual military weapon among some Asian nations. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Among the oldest cutting weapons are bronze dagger-blades from Cyprusfrom Crete. They were fitted into wooden or bone handles. A Cretan dagger-blade with an engraved design still holds the three dowels which fastened the haft. The tangs of the Cypriote blades are prolonged or hooked to prevent the blade from loosening in its socket. Spear-heads also were at first made to be inserted in the shaft, but later fitted over it. They have a slit on one side of the socket, probably to give elasticity. The bronze butt-spikes were used to fix the spear in the ground during halts.[Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

The sling consisted in a cord or strap, broad in the middle, and narrower at the two ends, by means of which little plummets were thrown; these were placed on the broad center of the strap, the two ends of which were pressed together in the hand and swung a few times round the head; with a careful aim they then let go one end of the strap, whereupon the shot flew in the direction which it had received by the impulse of swinging. In the heroic age the sling-shots were always stone balls; afterwards they also used plummets of clay or lead, very often in the shape of an acorn.

Many soldiers were outfit with a nine-foot spear (a wooden shaft with an iron point) and a short straight sword. There were also units of archers, perhaps using poison-tipped arrows. In the legend of Hercules there is story of how the hero defeated the multi-headed Hydra with flaming arrows dipped in pitch and there after kept poison collected from Hydra’s body and used that to poison his arrows. The word toxin is derived from the Greek word for arrow.

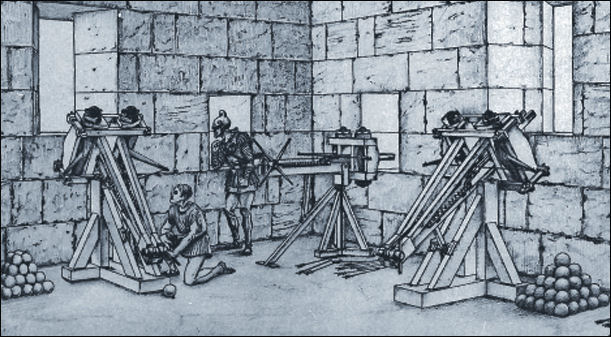

City states were walled. Under the guidance of the tyrant of Dionysuis I, engineers in Syracuse developed the catapult. "The catapult had an effective distance of up to 50 meters," a German archaeologist told National Geographic, "It could hurl not only stones but also arrows. No longer did people have to fight person-to-person. Catapults were moved across field on top of towers ten meters high. That was tall enough to attack an enemy inside his own walls."

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT GREEK ARMOR: SHIELDS, HELMETS AND 30-KILOGRAM PANOPLY europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT GREEK MILITARY factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SOLDIERS factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK ARMY: UNITS, ORGANIZATION, SUPPLY LINES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WARFARE IN ANCIENT GREECE: BATTLES. TACTICS, METHODS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ALEXANDER THE GREAT AND HIS ARMY: LEADERSHIP, TACTICS, WEAPONS, SUPPLY LINES, FOOD europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK NAVY: FIGHTING SHIPS AND SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SPARTAN MILITARY, TRAINING AND SOLDIER CITIZENS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Storm of Spears: Understanding the Greek Hoplite at War

by Christopher Matthew | Feb 20, 2019 Amazon.com;

“Arms and Armour of the Greeks” by Anthony M. Snodgrass (1967) Amazon.com;

“Greek Fire, Poison Arrows and Scorpion Bombs” by Adrienne Mayor (2003) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Artillery 399 BC–AD 363" by Duncan B Campbell and Brian Delf (2003) Amazon.com;

“Warriors of the Ancient Greek World: A Visual Guide to the Panoplies of War

by Kevin L. Giles (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece”

by Victor Davis Hanson and John Keegan (2009, 1989) Amazon.com;

“Reconstructing Ancient Linen Body Armor: Unraveling the Linothorax Mystery

Reconstructing Ancient Linen Body Armor: Unraveling the Linothorax Mystery” Amazon.com;

“Greek Hoplite 480–323 BC” (Warrior) by Nicholas Sekunda (Author), Adam Hook (Illustrator) (2000) Amazon.com;

"Hoplites at War: A Comprehensive Analysis of Heavy Infantry Combat in the Greek World, 750-100 BCE)" by Paul M. Bardunias and Fred Eugene Ray Jr. (2016)

Amazon.com;

“Greek Hoplite Vs Persian Warrior: 499–479 BC” by Chris MacNab (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Sacred Band: Three Hundred Theban Lovers Fighting to Save Greek Freedom” by James S. Romm (2021) Amazon.com;

“Soldiers and Ghosts” by J. E. Lendon (2005) Amazon.com;

“Anabasis” by Xenophon (1847) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Armies” by Peter Connolly (1977) Amazon.com;

“Armies of Ancient Greece Circa 500–338 BC: History, Organization & Equipment” by G. Esposito (2020) Amazon.com;

“Greece and Rome at War” by Peter Connolly (1981) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Military Manuals: Genre and History” by by James T. Chlup and Conor Whately (2020) Amazon.com;

“Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities” by Hans Van Wees (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Greek And Macedonian Art Of War” by F. E. Adcock (2015) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece” by Tim Everson (2004) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in the Classical World” by John Warry, illustrated (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Wars of the Ancient Greeks” by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“War and Violence in Ancient Greece” by Hans van Wees Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Michael M. Sage (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Greeks at War” by Louis Rawlings (2007) Amazon.com;

Materials Used to Make Ancient Greek Weapons

Bronze was arguably the most import material used to make Ancient Greek weapons. Caroline Alexander wrote in National Geographic: Bronze is harder than copper, harder indeed than iron, and bronze-pointed spears set on wooden shafts, bronze-tipped arrows, and bronze slashing and thrusting swords were objects of enormous utility, prestige, and value. Bronze is stronger than iron because it is an alloy of two other metals, making it denser and difficult to break with less friction. On the other hand, iron is a natural ore and less dense, and can be bent easily. Bronze can be melted easily, whereas iron needs a special furnace. Because it keeps an edge better than bronze and can more easily be shaped of furnaces are hot enough, iron proved to be an ideal material for improving weapons and armor as well as plows.

Bone, hooves and wood were also used to make weapons. Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): Among the votive offerings there is a Sauromatic breast plate. On seeing this a man will say that no less than Greeks are foreigners skilled in the arts. For the Sauromatae have no iron, neither mined by them selves nor yet imported. They have, in fact, no dealings at all with the foreigners around them. To meet this deficiency they have contrived inventions. In place of iron they use bone for their spear-blades, and cornel-wood for their bows and arrows, with bone points for the arrows. They throw a lasso round any enemy they meet, and then turning round their horses upset the enemy caught in the lasso.

Ancient Greek Spear

Throwing weapons were chiefly used by light-armed troops. In the heroic ages the javelin was only a hunting weapon; the heroes usually used their ordinary long lances for throwing. The light javelin, about two and three-quarter yards in length, became a very common weapon of attack in the next period, when the light-armed troops formed a regular part of the army; this closely resembled the javelin used in the athletic contests, especially in the Pentathlon, and like this was provided with a loop, which the thrower wound round his fingers. We have already discussed the method of throwing this spear.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The spear, or lance, consisted in a shaft usually made of ash, provided at both ends with a bronze point; one of these points was used for attack, the other to fix the spear in the ground when it was not required. The material for the point, in the heroic age, was usually bronze; in later times, iron. The blade of the point required for attack was usually leaf-shaped and two-edged; its length was from 7 to 8 inches, its breadth about 2½ in the middle; it was fastened to the upper pointed end of the shaft by a socket, and this socket was surrounded by a ring in order to increase the firmness. The lower end was usually only a short conical point. The length of the spear was greater in the heroic age than afterwards.

Homer mentions spears about five yards long, and in naval warfare even one about ten yards long, but this was constructed of several pieces fastened together, and was probably only used in naval warfare to keep off the grappling irons; in later times the usual length was from two to two and a quarter yards. That is about the length of the spears represented in three images. We often find two spears in the hand of a warrior; this usually happened when the soldier used his long spear not only for thrusting, but also for throwing, in which case he would require a reserve spear. In thrusting, as well as in throwing, he clasped the spear in the middle with the right hand alone. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Ancient Greek Swords

The sword is an even more useful weapon for hand-to-hand combat than the spear, which on account of its length can only be used from some distance. Originally swords were constructed of bronze, and this is the only kind mentioned by Homer, afterwards of iron; the blade was two-edged, and in the heroic age tolerably long, probably shaped like that which was brought from Mycenae and is twenty-four inches long; the two-edged blade and the top of the handle, which was decorated by plates of wood, bone, or such like, fastened on by nails, but which has not been preserved, were formed of a single piece. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

As this sword and the others resembling it were equally well calculated for thrusting and piercing. The swords in other images, also from Mycenae, are of a different kind; the blades are two-edged, and measure thirty-two inches in length; the top of the haft is formed of the same piece with the blade, and covered with plates of a different material, but this weapon seems to have been exclusively used for piercing. Of another kind are those in two images, but these date from Italian lake dwellings, though the same kind is said to have been also found in Greece. The two-edged blade is short here, very broad at the top, but growing gradually narrower, so that the shape almost resembles an acute-angled triangle. The handle, the lower end of which is bent outwards in the shape of a semicircle, is worked out of a separate piece of bronze, and connected with the blade by nails.

An iron sword from Cyprus preserves the form of the bronze swords of the late Mycenaean period, as the early iron-workers at first imitated the shapes of bronze weapons. The pin in the shape of a sword illustrates the type in use during the fifth century in Greece. The machaira which Xenophon often mentions had a curved blade and was especially useful as a cutting weapon for cavalry. A good illustration of this shape may be seen in a painting on an amphora representing a Greek and a Persian fighting. The Persian holds a machaira ready for the down-stroke. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

In the historic age the swords are usually short, the blade about twenty inches long, reed-shaped, and two-edged, adapted for thrusting and piercing; the handle, which is generally suited for parrying strokes, is rather small. The sheath was often of some costly material, and artistically decorated, ordinary kinds were made of leather; the shoulder-belt was usually a leather strap, with metal plates; it was suspended over the right shoulder, and was so long that the sword hung down by the left side, but in later times they sometimes wore the sword on the right side. Besides the kinds of swords already mentioned there were some others; in particular that which is specially designated as the Spartan sword, the blade of which is slightly curved on one side from the handle onwards, and very sharp, while the other edge is straight and evidently blunt; this kind of sword could of course only be used for thrusting. Towards the end of the Hellenic period, Iphicrates again introduced long swords in the Greek armies; they measured as much as a yard with the haft, but the heavy-armed infantry probably continued to use the short sword.

Ancient Greek Bow and Arrows

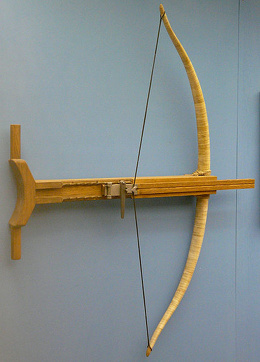

There were two kinds of bows: in the first place, a simple one formed of a single piece of elastic wood bent outwards at the ends; its form is slightly bent, and only attains the shape of a strong curve when it is drawn. This bow was called the “Scythian,” or “Parthian,” but we find it also on Greek works of art, and it was probably the older kind. The other shape is that of the double bow, in which two curved pieces of horn are connected together by a cylindrical piece of metal; this shape was the commoner in the Greek army, and even when they gave up using goat and gazelle horns for the bow, but constructed it of wood, it retained the shape. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The metal plate in the middle was also used as a rest for the arrow, and the ends of the bow to which the string was fastened, were usually plated with metal. The cord was made of plaited guts, and as a rule, when the bow was not in use, was fastened only to one end, and hung down loose, in order that the bow might not lose its elasticity through the constant strain of the string. The arrow was a shaft about twenty-four inches long, usually of light reed, on which the point, supplied with two or more barbs, was fastened with a string; at the other end, it usually had a little weight, supplied with a notch for setting it more firmly against the string. We have evidence in Greek excavations of the three-edged arrow mentioned by Homer; compare an arrow-head from Megalopolis. The arrows were kept in a quiver made of leather or basket-work, of which two kinds are found: one wide kind of triangular form, worn on the left side, and generally used with the so-called Scythian bow; and a smaller cylindrical shape, which hung down on the back over the left shoulder, and belonged to the Greek bow.

Weapons or Alexander the Great's Army

Alexander’s army was made up of around 50,000 men (an enormous number at that time when great cities had a population of 10,000 or 20,000). Among the foot soldiers were archers, equipped with short bows; Greek hoplites, skilled veteran soldiers; shield bearers, who carried weapons and assisted the hoplites; slingers, who threw stones with slings; and trumpeters who relayed messages on the battlefield.

Alexander’s soldiers relied on the “sarissae”, or pike, a 4.3-meter-long spear that was twice as long as a standard spear. Archers used powerful short bows. Slingers threw stones to harass the enemy. Soldiers were armed with swords and wore armored helmet and breastplate like the Greeks and used a round shield for protection. The cavalry rode horses with rudimentary saddles with no stirrups.

While the Persians and others relied on long bows the Greeks amd Macedonians were primarily hand-to-hand combatants who relied on swords and thrusting pikes. Sarissae were wooden pikes. They were generally around three meters longer than the average spear and this gave them a range advantage.

Ancient Greek Biochemical Weapons

The Greeks reportedly objected to the use of toxic weapons and underhanded fighting methods because pf their sense of a “fair fight.” Even so they did things like dump rotting animals into the wells and catapulted plague and smallpox victims over the walls of their enemies. Some scholars believe that they tipped arrows with snake venom and that poison arrows may have played a role in the outcome of the Trojan War. Homer described black blood flowing from wounds and the use of leeches to suck the blood from such wounds. There were clear signs of snake poisoning.

The ancient Greeks and other peoples of Antiquity used viper venom, poison gas, and deadly pathogens as weapons. Adrienne Mayor wrote in National Geographic History: Desperate cities under siege resorted to biological options to keep invaders at bay. Generals ordered biochemical attacks out of frustration with long sieges and stalemates or to avoid casualties and the uncertainties of a fair fight. Holy or sacred wars encouraged the ruthless killing of enemy civilians as well as soldiers. Whenever a population was identified as uncivilized, or less than human, there were few qualms about using inhumane weapons. [Source: Adrienne Mayor, National Geographic History, May 25, 2023]

Incidents of biological warfare have been documented in numerous ancient texts. More than 50 authors provide evidence that biological and chemical weapons saw action in historical battles around the Mediterranean, India, and China. The sheer variety of options was staggering. Besides shooting arrows steeped in snake venom, germs, toxic plants, and fiery materials, ancient armies also contaminated their enemies’ water.

Not all historical examples of “biochemical” tactics in antiquity fit modern scientific definitions, but they do represent the earliest evidence of the intentions, principles, and actual practices that would evolve into present-day biochemical weapons. Chemical weapons are defined as poison gases, choking and blinding clouds of smoke, and combustible incendiaries unquenched by normal means. Biological weapons are harvested from living organisms (such as animal venom and poisonous plants) or are full-fledged pathogens themselves that infect the human body. The use of animals was the precursor of entomological and zoological weapons research actively pursued today.

Book: “ Greek Fire, Poison Arrows & Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World” by Adrienne Mayor (The Overlook Press).

Hellenistic Artillery Tower Reconstruction

Using Snakes and Scorpions as Weapons

Adrienne Mayor wrote in National Geographic History: Sometimes venomous animals themselves were used as weapons, their effectiveness stemming not just from their toxicity but also from the fear they could unleash in the enemy. In a naval battle fought in around 184 B.C. between Hannibal and the Hellenistic king Eumenes II of Pergamum, Hannibal stuffed poisonous snakes into amphorae that he catapulted onto the enemy ships. Eumenes’s men were unable to move their ships to dodge the slithering bioweapons, and Hannibal won the battle. In A.D. 198–199, the Parthians defending Hatra threw clay pots filled with poisonous critters at Septimius Severus’s legionnaires. The bombs caused injuries to their eyes and exposed parts of the body, suggesting that they were scorpions, assassin bugs, wasps, or Paederus (rove) beetles. [Source: Adrienne Mayor, National Geographic History, May 25, 2023]

Archaeological excavations of Scythian warriors — nomad archers of the Eurasian steppes — buried with their quivers reveal that they used wickedly barbed arrows affixed to wooden shafts. The shafts were decorated with patterns to resemble venomous vipers. Facing a hail of arrows painted to look like flying snakes with deadly fangs would have been daunting enough, but the experience was even more harrowing, for the Scythians dipped their arrowheads in a notorious poison called scythicon. Ancient Greek sources described it as a nasty concoction of snake venom, decomposed vipers’ bodies, human blood, and dung. The ingredients were combined and then allowed to putrefy over several months. A slight scratch from one of these arrows brought a ghastly death or a slow torture from a wound infected with gangrene and tetanus.

Venom from Russell’s viper (Daboia ruselii) was used to attack Harmatelia. The deadly scorpion became a symbol, painted on the shield of the Hoplites and later taken as an emblem by the Pretorian Guard. It is interesting that both the Scythians and the Harmatelians used the entire bodies of vipers to make arrow poisons. A modern herpetological discovery suggests a good reason: a snake’s stomach contains harmful bacteria. Moreover, scientists recently learned that vipers retain surprisingly large amounts of feces in their bodies. A dead viper’s excrement would add even more foul bacteria to the mixture.

Spartans Incendiary Weapons

Spartans used sulphur and pitch in warfare and created poison gas and a flame throwing machine to attack fortified positions in the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides described the Spartan use of incendiary weapons as the "most devastating manmade conflagration ever seen" in their attempt to destroy the city of Platania in 430 B.C. They used a flaming mixture of pitch and sulfur against the Athenians at Delium in 424 B.C.

Adrienne Mayor wrote in National Geographic History: Fire also led to one of the earliest historical instances of using poison gas against an enemy. In 429 B.C., during the Peloponnesian War, Spartan forces attacked the fortified city of Plataea. The historian Thucydides tells how the Spartans heaped a massive pile of firewood next to the city wall, then poured pine tree resin (pitch, the source of turpentine) on the logs. [Source: Adrienne Mayor, National Geographic History, May 25, 2023]

In a bold innovation, the Spartans then added lumps of sulfur, found in acrid-smelling mineral deposits in volcanic areas and hot springs. The combination of pitch and sulfur accelerants “produced a conflagration that had never been seen before, greater than any fire produced by human agency,” declared Thucydides.

Indeed, the blue sulfur flames and foul stench must have been sensational. The fumes were deadly; burning sulfur creates toxic sulfur dioxide gas, lethal if inhaled in large quantities. The Plataeans abandoned their burning palisades, but then the wind reversed and a severe thunderstorm put out the fire. Plataea was saved.

In the 4th century B.C. Aeneas the Tactician’s book on surviving sieges devoted a whole section to fending off chemically-enhanced fires. One of his chief recommendations was to fight the fire with fire by pouring pitch on enemy soldiers or their siege machines, followed by bunches of hemp and lumps of sulfur, and then using flaming bundles of kindling to ignite them.

Ancient Greek Flame Throwers

According to National Geographic: The Boeotians mounted a flame-throwing contraption onto a chariot and wheeled it in front of the wooden walls of Delium. Then they pumped the bellows, sending a current of air into the cauldron and fanning the embers within. The flammable elements that were packed into the cauldron burst into flames and leapt from its mouth toward the city walls.

In 424 B.C., Sparta’s allies, the Boeotians, invented a “flamethrower” device to sidestep shifting winds. Thucydides described how the contraption destroyed the wooden fortifications at Delium, held by the Athenians. The Boeotians hollowed out a huge wooden log and plated it with iron. They suspended a large cauldron by a chain attached to one end of the hollow beam and inserted an iron tube, curving down into the cauldron. [Source: Adrienne Mayor, National Geographic History, May 25, 2023]

The cauldron was filled with burning coals, pine resin, and sulfur — the same accelerants innovated by the Spartans at Plataea. Mounted on a cart, the apparatus was wheeled next to the walls. The Boeotians attached a very large blacksmith’s bellows to their end of the beam and pumped great blasts of air through the tube to direct the chemical fire and toxic gases at the walls. The walls were incinerated, as were defenders as they fled their posts, and Delium was captured.

As noxious smoke was hard to control and direct, it was often easier to employ in confined spaces like tunnels. In western Greece in A.D. 189, during the long siege of Ambracia, the defenders invented a smoke machine to repel the Roman sappers tunneling under the city walls. Polyaenus says the Ambracians “prepared a large jar equal in size to the tunnel, bored holes into the bottom, and inserted an iron tube.” They packed the pot with layers of fine chicken feathers and smoldering charcoal and capped the jar with a perforated lid.

Then they aimed the perforated end of the jar of burning feathers at the tunnelers and fitted blacksmith’s bellows to the iron tube at the other end. With this device — which calls to mind the primitive flamethrower at Delium — the Ambracians filled the passage with clouds of acrid smoke, sending the choking Romans rushing to the surface. “They abandoned their subterranean siege,” was Polyaenus’s terse comment.

But why did the Ambracians burn chicken feathers? It turns out that feathers are composed of keratins containing cysteine, a sulfuric amino acid. Burning the feathers releases sulfur dioxide, the very same kind of gas used by the Spartans at Plataea and Boeotians at Delium. Of course, the Ambracians were not aware of the scientific explanation. They knew only that burning chicken feathers produced a notoriously toxic effect, especially in a tunnel.

Greek Fire

The Byzantines discovered that by adding sulphur or quicklime and saltpeter to naptha they could create a material capable of spontaneous combustion and produce bombs that could be thrown at enemies that would explode on impact. This napalm-like "Greek fire" was used in A.D. 673 and 678 to fend off attacks on Constantinople by Arabs.

In 10th century the Byzantines invented the flame thrower, a powerful secret weapon that changed the nature of warfare. The devise used Greek fire that was preheated under pressure and discharged in liquid form with pump-powered, syringe-like bronze tubes. It was used primarily in sea battles, when it incinerated wooden ships and their crews and even spread fire on the water. Russia's Prince Igo purportedly lost 10,000 vessels to Greek fire in a battle in 941.☼

Fire weapons made Byzantine ships masters of the sea for centuries. Byzantine war ships were outfit with catapults used to fire "Greek fire" grenades and cannons. Greek Fire was also used on land: pressurized siphons were fired at forts, squirt guns and ceramic hand grenades were used at close range in hand-to-hand battles,

The recipe for Greek Fire was a carefully guarded secret. It is believed that early versions were devised by Callinicus, a A.D. seventh-century engineer from Syria, where people had been using flammable petrochemicals for some time. Scholars are still not sure of the ingredients. It was likely a highly combustible mixture of quicklime, sulphur, naptha and saltpeter. It was particularly nasty because it clung to whatever it touched and was not quenched by water. Clothing and ship sails were often ignited and people could not put out the fires by jumping into the sea.

The use of Greek Fire was regarded with horror and moral disgust. There is no mention of it from A.D. 800 and 1000 and some scholars believed it may have been banned because it was "too murderous."

Carnyx Eery Sounds Struck Fear Into Enemy Soldiers

Oliver Parken wrote in The Warzone, During the Iron Age and Greek/Roman periods, a specific instrument was used to make the loudest, and most fear-inducing sounds possible — the carnyx. These valveless, trumpet-like instruments were colossal — standing as tall, or even taller, than the people who played them. Made of beaten metal in a distinctive ' ' shape, the carnyx featured a long central tube section, allowing for low bass and shrieking high notes to be created, with a mouthpiece for blowing at one end. Typically, they had an ornately crafted horn at the top end sculpted into the shape of an animal’s head — often in the style of a boar, symbolizing the harsh, guttural sounds produced. [Source: Oliver Parken, The Warzone, December 16, 2023]

Textual references, as well as archeological discoveries, indicate the carnyx was used widely throughout western and central Europe between 300 B.C. and 200 AD, with the instrument having a particular affinity within various Celtic tribes. However, it should be noted that they were used further afield too, with representations of the carnyx having been discovered within Buddhist sculptures in India from the period. The carnyx was clearly seen, and heard, far and wide as Celtic mercenaries expanded the outer reach of Iron Age society.

According to the Greek historian Polybius (206-126 B.C.), for example, the cacophony of sounds produced by Gallic forces using carnyces was truly terrifying: "There were countless trumpeters and horn blowers and since the whole army was shouting its war cries at the same time there was such a confused sound that the noise seemed to come not only from the trumpeters and the soldiers but also from the countryside which was joining in the echo." The Roman historian Diodorus Siculus similarly describes the trumpets of a "peculiar barbarian kind" used by Western European tribes. "They blow into them and produce a harsh sound which suits the tumult of war."

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see The Carnyx’s Eerie Cry Struck Fear Into Soldiers On Antiquity’s Battlefields twz.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024