Home | Category: Greek Classical Age (500 B.C. to 323 B.C.) / Military

FIGHTING AT THE BEGINNING OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR

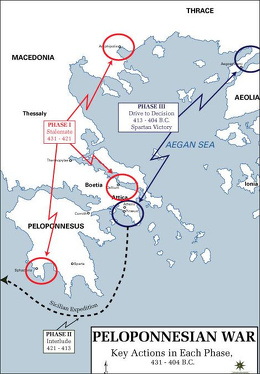

The 27-year Peloponnesian War (431 B.C. to 404 B.C.) is named after the Peloponnesian League, an alliance led by Sparta that included Corinth and Thebes, that dominated the Peloponnesian peninsula . Sparta had traditionally been stronger militarily than Athens but Athens was stronger and richer as a result of tributes pouring in through the Delian League — an alliance that stretched across the Mediterranean. The resulting imbalance had much to do with the why the war was fought.

The 27-year Peloponnesian War (431 B.C. to 404 B.C.) is named after the Peloponnesian League, an alliance led by Sparta that included Corinth and Thebes, that dominated the Peloponnesian peninsula . Sparta had traditionally been stronger militarily than Athens but Athens was stronger and richer as a result of tributes pouring in through the Delian League — an alliance that stretched across the Mediterranean. The resulting imbalance had much to do with the why the war was fought.

After a diplomatic crisis involving the Corinth ties between Athens and Sparta fell part. Fighting began with a sneak attack in 431 B.C. on the small Athenian protectorate called Plataea, a move widely viewed as an egregious violation of the Greek etiquette of warfare and set the tone for things to come. Yale historian Donald Kagan wrote the hostilities set off cycle of cruelty and reprisals that ended in a “collapse of in the habits, institutions, beliefs and restraints that are the foundations of civilized life.”

Sparta and its allies, with the exception of Corinth, were almost exclusively land-based powers, able to summon large land armies which were very nearly unbeatable (thanks to the legendary Spartan forces). The Athenian Empire, although based in the peninsula of Attica, spread out across the islands of the Aegean Sea; Athens drew its immense wealth from tribute paid from these islands. Athens maintained its empire through naval power. Thus, the two powers were relatively unable to fight decisive battles. [Source: Wikipedia]

Athens won a series of important battles at the beginning of the war. Athens clearly had the advantage at the outset because Sparta had no navy. To counter Sparta’s dominance on land, the Athens adopted the foolishly passive defensive strategy of remaining within their Long Wall — which surrounded Athens and its port in Piraeus 10 kilometers away — and putting up with the Spartans burning their crops, by relying on their navy to ship in food supplies from its Mediterranean allies.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THUCYDIDES europe.factsanddetails.com

MITYLENIAN DEBATE AND MELIAN DIALOGUE: PUNISHMENT, COMPASSION, POLITICAL REALISM DURING THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

END OF CLASSICAL GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) and After, See Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University sourcebooks.web.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Peloponnesian War” by Donald Kagan (2003) Amazon.com;

“A War Like No Other” by Victor Davis Hanson (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece” by Jennifer Roberts (2017) Amazon.com;

“History of the Peloponnesian War” by Thucydides (1834) Amazon.com;

“Thucydides, The Reinvention of History” by Donald Kagan, (Viking, 2009) Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Thucydides” Amazon.com;

“Athens and Sparta: Constructing Greek Political and Social History from 478 BC” by Anton Powell (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Spartan Army” by John Lazenby (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Spartan Army” by Nicholas Sekunda (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Athens: The Story of the World's Greatest Civilization” by Anthony Everitt (2016) Amazon.com;

“Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy” by John R. Hale (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Athens” by Plutarch (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Athenian Empire” by Russell Meiggs (1972) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece” by Josiah Ober (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Greek World, 479-323 BC” by Simon Hornblower (1983) Amazon.com;

“A Chronology of Ancient Greece” by Timothy Venning (2015) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in the Classical World” by John Warry, illustrated (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Wars of the Ancient Greeks” by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

“War and Violence in Ancient Greece” by Hans van Wees Amazon.com;

“Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook” by Michael M. Sage (1996) Amazon.com;

Archidamian War: the First Peloponnese War

The Spartan strategy during the first war, known as the Archidamian War (431–421 BC) after Sparta's king Archidamus II, was to invade the land surrounding Athens. While this invasion deprived Athenians of the productive land around their city, Athens itself was able to maintain access to the sea, and did not suffer much. Many of the citizens of Attica abandoned their farms and moved inside the Long Walls, which connected Athens to its port of Piraeus. At the end of the first year of the war, Pericles gave his famous Funeral Oration (431 BC).[Source: Wikipedia +]

The Spartans also occupied Attica for periods of only three weeks at a time; in the tradition of earlier hoplite warfare the soldiers were expected to go home to participate in the harvest. Moreover, Spartan slaves, known as helots, needed to be kept under control, and could not be left unsupervised for long periods of time. The longest Spartan invasion, in 430 BC, lasted just forty days. +

The Athenian strategy was initially guided by the strategos, or general, Pericles, who advised the Athenians to avoid open battle with the far more numerous and better trained Spartan hoplites, relying instead on the fleet. The Athenian fleet, the most dominant in Greece, went on the offensive, winning a victory at Naupactus. In 430 BC an outbreak of a plague hit Athens. The plague ravaged the densely packed city, and in the long run, was a significant cause of its final defeat. The plague wiped out over 30,000 citizens, sailors and soldiers, including Pericles and his sons. Roughly one-third to two-thirds of the Athenian population died. Athenian manpower was correspondingly drastically reduced and even foreign mercenaries refused to hire themselves out to a city riddled with plague. The fear of plague was so widespread that the Spartan invasion of Attica was abandoned, their troops being unwilling to risk contact with the diseased enemy. +

Thucydides on Civil War in Corcyra

In the fifth year of the Peloponnesian war (427 B.C.), Athens' ally Corcyra fell victim to internal strife, a vicious struggle between the commons, allies of Athens, and the oligarchs, who were eager to enlist the support of the Spartans. The revolt began when Corinth, an ally of Sparta, released Corcyraean prisoners with the promise that the former prisoners would work to convince Corcyra to abandon its ally Athens and join the Peloponnesian side. These men brought Peithias, a pro-Athenian civic leader, to trial on charges of "enslaving Corcyra to Athens" (Thucydides, 3.71.1). He was acquitted and took revenge by charging five of them in turn. However, these men burst in upon the senate and killed Peithias and sixty other people. Shortly after this, skirmishes broke out in the city, between the commons, who enlisted the aid of the slaves, and the oligarchs, who hired mercenaries, which ended with the oligarchs being routed. The Athenian general, Nicostratus, tried to bring about a peaceful settlement and ensure an offensive and defensive alliance between Corcyra and Athens. [Source: Tufts]

On the impact of this conflict on individuals and society, Thucydides: wrote in “History of the Peloponnesian War” Book 3.82-83: “So savage was the factional strife that broke out - and it seemed all the worse in that it was the first to occur. Later on, indeed, all of Hellas (so to speak) was thrown into turmoil, there being discord everywhere, with the representatives of the demos (i.e. the extreme democratic factions) wanting to bring in the Athenians to support their cause, while the oligarchic factions looked to the Spartans. In peacetime they would have had no excuse nor would they have been prepared to summon them for help, but in the midst of a war, the summoning of outside aid readily offered those on both sides who desired a change in the status quo alliances that promised harm for their opponents and, at the same time, benefit for themselves. [Source: Thucydides: “History of the Peloponnesian War” Book 3.82-83, translated by John Porter, University of Saskatchewan, 1995]

“Many harsh events befell the various cities due to the ensuing factional strife - things which always occur in such times and always will occur, so long as human nature (physis) remains the same, although with varying degrees of violence, perhaps, and differing in form, according as variations in circumstances should arise. For in peacetime, and amid prosperous circumstances, both cities and individuals possess more noble dispositions, because they have not fallen into the overpowering constraints imposed by harsher times. But war, which destroys the easy routines of people's daily lives, is a violent schoolmaster, and assimilates the dispositions of most people to the prevailing circumstances.

“So then, affairs in the cities were being torn apart by faction, and those struggles that occurred in the latter stages of the war - through news, I suppose, of what had occurred earlier in other cities - pushed to greater lengths the extravagance with which new plots were devised, both in the inventiveness of the various attempts at revolt and in the unheard-of nature of the subsequent acts of retaliation.

“And people altered, at their pleasure, the customary significance of words to suit their deeds: irrational daring came to be considered the "manly courage of one loyal to his party"; prudent delay was thought a fair-seeming cowardice; a moderate attitude was deemed a mere shield for lack of virility, and a reasoned understanding with regard to all sides of an issue meant that one was indolent and of no use for anything. Rash enthusiasm for one's cause was deemed the part of a true man; to attempt to employ reason in plotting a safe course of action, a specious excuse for desertion. One who displayed violent anger was "eternally faithful," whereas any who spoke against such a person was viewed with suspicion. One who laid a scheme and was successful was "wise," while anyone who suspected and ferreted out such a plot beforehand was considered still cleverer. Any who planned beforehand in order that no such measures should be necessary was a "subverter of the party" and was accused of being intimidated by the opposition. In general, the one who beat another at performing some act of villainy beforehand was praised, as was one who urged another on to such a deed which the latter, originally, had no intention of performing.

Athen's Long Wall helped keep it supplied by the sea

“Indeed, even kinship came to represent a less intimate bond than that of party faction, since the latter implied a greater willingness to engage in violent acts of daring without demur. For such unions were formed, not with a view to profiting from the established laws, but with a view toward political advantage contrary to such laws. And their mutual oaths they cemented, not by means of religious sanction, but by sharing in some common crime.

“Fair proposals offered by the opposing faction were accepted by the party enjoying the superior position in a guarded fashion, not in a truly generous spirit. More concern was placed on exacting vengeance from someone else than on not suffering a wrong yourself in the first place. And if ever oaths of reconciliation did come about, having been exchanged in the face of some temporary difficulty, they remained in force only so long as the parties possessed no resources from any other source. The one who was quicker to seize the opportunity for some daring outrage, if ever he saw his opponent off his guard, took more pleasure in taking vengeance in this way than if he had done so openly, considering this method to be safer and thinking that, by getting the upper hand through deceit, he had won in addition the prize for cleverness. And indeed, most people accept more readily being called clever, when they are knaves, than being called fools when they are honest: the latter they take shame in, whereas they preen themselves on the former.“The cause of all of these things was the pursuit of political power, motivated by greed and ambition. And out of these factors arose the fanatical enthusiasm of individuals now fully disposed to pursue political vendettas.

For the leading men on both sides in each city, employing fine-sounding phrases and advocating either equality before the law for the masses (in the case of the democrats) or the moderate rule of the best men (in the case of the oligarchs) made a show of serving the common good but in fact engaged in competition for personal advancement. Competing in every possible fashion to get the better of their opponents, they went to the farthest extremes of daring and executed even greater acts of vengeance, not limiting themselves by the demands of justice or the interests of the city, but only by their whims at any particular moment. In their efforts to gain power either through the use of trumped up lawsuits or by force, they were always ready to pursue the political vendetta of the moment. The result was that neither side was wont to pay any regard to personal integrity: those who succeeded in accomplishing some act of malice under cover of some fine phrase were the ones to gain general approval. By contrast, those citizens who chose the middle course of moderation perished at the hands of both factions, either for their failure to join in the struggle or due to envy at the fact that they were surviving amid the general chaos.

“Thus moral degeneration of every type took hold throughout Hellas due to factional strife, and simplicity of character — with which a concern for honor is intimately connected — became an object of mockery and disappeared. People were ranged against one another in opposite ideological camps, with the result that distrust and suspicion became rampant. (2) For there was no means that could hope to bring an end to the strife — no speech that could be trusted as reliable, no oath that evoked any dread should it be broken. Everyone, when they had the upper hand, reckoned that there was no hope of any security by means of promises or oaths, and so concentrated on taking precautions not to suffer any injury rather than daring to trust anyone. (3) And, for the most part, those of more limited intelligence were the ones to survive: in their fear regarding their own deficiencies and their opponents' cleverness, lest they might be defeated in debate (e.g. in a political trial) or be forestalled in laying some plot by their opponents' cunning, they turned to action right away with a boldness born of desperation. Their opponents, overconfident in their assurance that they could anticipate the plots of their less intelligent antagonists, and feeling that they could attain their ends by cunning rather than by force, tended to be caught off guard and so perished.”

plague in an ancient city

Plague in Athens in 430 B.C.

Things began going badly for the Athenians when the plague struck in 430 B.C. and killed a quarter to a third of the city’s population. The mysterious disease began in Ethiopia and passed through Egypt and Libya to Greece in 430-426 B.C. The plague ripped through the city-state's military, killed Pericles, affected the course of the Peloponnese war, changed the balance of power between Athens and Sparta, and ending the Golden Age of Athens and Athenian dominance in the ancient world.

No one is sure exactly what disease the plague of Athens was. Some believe it was the Ebola virus, or perhaps the bubonic plague, smallpox, anthrax or measles. It had same symptoms of typhus fever but otherwise was not like any known disease. Knowledge of the epidemic is based largely on an account by Thucydides, who was sickened by the plague but recovered.

In 2006, scientists from the University of Athens announced that the Great Plague of Athens was actually an outbreak of typhoid. According to Live Science: “A new DNA analysis of teeth from an ancient Greek burial pit indicates typhoid fever caused the epidemic. The study, led by Manolis Papagrigorakis of the University of Athens, found DNA sequences similar to those of the modern day Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, the organism that causes typhoid fever. The study was by the International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Typhoid fever is transmitted by contaminated food or water. It is most common today in developing countries. [Source: Live Science, January 23, 2006]

See Separate Article: DISEASE IN ANCIENT GREECE: CANCER, PLAGUES, HYSTERIA factsanddetails.com

Battle of Sphacteria, Peace of Nicias, Battle of Mantinea

After the death of Pericles, the Athenians turned somewhat against his conservative, defensive strategy and to the more aggressive strategy of bringing the war to Sparta and its allies. Rising to particular importance in Athenian democracy at this time was Cleon, a leader of the hawkish elements of the Athenian democracy. Led militarily by a clever new general Demosthenes (not to be confused with the later Athenian orator Demosthenes), the Athenians managed some successes as they continued their naval raids on the Peloponnese. Athens stretched their military activities into Boeotia and Aetolia, quelled the Mytilenean revolt and began fortifying posts around the Peloponnese. One of these posts was near Pylos on a tiny island called Sphacteria, where the course of the first war turned in Athens's favour. The post off Pylos struck Sparta where it was weakest: its dependence on the helots, who tended the fields while its citizens trained to become soldiers. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Battle of Sphacteria at Pylos

The helots made the Spartan system possible, but now the post off Pylos began attracting helot runaways. In addition, the fear of a general revolt of helots emboldened by the nearby Athenian presence drove the Spartans to action. Demosthenes, however, outmanoeuvred the Spartans in the Battle of Pylos in 425 BC and trapped a group of Spartan soldiers on Sphacteria as he waited for them to surrender. Weeks later, though, Demosthenes proved unable to finish off the Spartans. After boasting that he could put an end to the affair in the Assembly, the inexperienced Cleon won a great victory at the Battle of Sphacteria. The Athenians captured 300 Spartan hoplites. The hostages gave the Athenians a bargaining chip. +

After these battles, the Spartan general Brasidas raised an army of allies and helots and marched the length of Greece to the Athenian colony of Amphipolis in Thrace, which controlled several nearby silver mines; their product supplied much of the Athenian war fund. Thucydides was dispatched with a force which arrived too late to stop Brasidas capturing Amphipolis; Thucydides was exiled for this, and, as a result, had the conversations with both sides of the war which inspired him to record its history. Both Brasidas and Cleon were killed in Athenian efforts to retake Amphipolis (see Battle of Amphipolis). The Spartans and Athenians agreed to exchange the hostages for the towns captured by Brasidas, and signed a truce. +

With the death of Cleon and Brasidas, zealous war hawks for both nations, the Peace of Nicias was able to last for some six years. However, it was a time of constant skirmishing in and around the Peloponnese. While the Spartans refrained from action themselves, some of their allies began to talk of revolt. They were supported in this by Argos, a powerful state within the Peloponnese that had remained independent of Lacedaemon. With the support of the Athenians, the Argives succeeded in forging a coalition of democratic states within the Peloponnese, including the powerful states of Mantinea and Elis. Early Spartan attempts to break up the coalition failed, and the leadership of the Spartan king Agis was called into question. Emboldened, the Argives and their allies, with the support of a small Athenian force under Alcibiades, moved to seize the city of Tegea, near Sparta. +

The Battle of Mantinea was the largest land battle fought within Greece during the Peloponnesian War. The Spartans (Lacedaemonians), with their neighbors the Tegeans, faced the combined armies of Argos, Athens, Mantinea, and Arcadia. In the battle, the allied coalition scored early successes, but failed to capitalize on them, which allowed the Spartan elite forces to defeat the forces opposite them. The result was a complete victory for the Spartans, which rescued their city from the brink of strategic defeat. The democratic alliance was broken up, and most of its members were reincorporated into the Peloponnesian League. With its victory at Mantinea, Sparta pulled itself back from the brink of utter defeat, and re-established its hegemony throughout the Peloponnese. +

The Battle of Delium took place in 424 BC, during the Peloponnesian War. It was fought between the Athenians and the Boeotians, who were allies of the Spartans, and ended with the siege of Delium in the following weeks.

Tide Turns Against Athens in the Peloponnesian War

The Athenians would eventually go on to carry out a number of atrocities. In 416 B.C., under the Alcibiades, they invaded the island of Melos, killing all the men and enslaving everyone else for the crime of being neutral. For many historians this event was the watershed of Athens’s moral decline. The Spartans also used underhanded tactics. After Athens attacked the Spartan port of Gytheion and set fire to Spartan ships, Spartan soldiers retaliated by disguising themselves as visiting athletes and retook the port.

The tide turned after Sparta received aid from its old enemy Persia. By this time Sparta’s tactic of burning crops was really beginning to take its toll. Violent internal strife, economic problems and a succession of oppressive regime was ripping Sparta apart from the inside. Sparta’s alliance with Persian gave it an economic crutch enabling it to weather its own troubles and build an army and navy at a critical moment.

The decisive battle occurred on Sicily at Syracuse, an ally of Sparta. The event occupies two full books of Thucydides account of the war, The flamboyant general Alcibades persuaded the Athenian assembly to send a huge armada to attack Syracuse. In the Battle of Syracuse the underdog Sicilians routed the Athenians after they sailed into their harbor and were trapped. The Athenian armada was decimated at the Aegispotami in the Hellespont in 405 B.C. .

Sicilian Expedition

The decisive battle occurred on Sicily at Syracuse, an ally of Sparta. The event occupies two full books of Thucydides account of the war, The flamboyant general Alcibades persuaded the Athenian assembly to send a huge armada to attack Syracuse. In the Battle of Syracuse the underdog Sicilians routed the Athenians after they sailed into their harbor and were trapped. The Athenian armada was decimated at the Aegispotami in the Hellespont in 405 B.C. .

In the 17th year of the war, word came to Athens that one of their distant allies in Sicily was under attack from Syracuse. The people of Syracuse were ethnically Dorian (as were the Spartans), while the Athenians, and their ally in Sicilia, were Ionian. The Athenians felt obliged to assist their ally. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Southern Italy and Greece at the time of the Sicilian Expedition

The Athenians did not act solely from altruism: rallied on by Alcibiades, the leader of the expedition, they held visions of conquering all of Sicily. Syracuse, the principal city of Sicily, was not much smaller than Athens, and conquering all of Sicily would have brought Athens an immense amount of resources. In the final stages of the preparations for departure, the hermai (religious statues) of Athens were mutilated by unknown persons, and Alcibiades was charged with religious crimes. Alcibiades demanded that he be put on trial at once, so that he might defend himself before the expedition. The Athenians however allowed Alcibiades to go on the expedition without being tried (many believed in order to better plot against him). After arriving in Sicily, Alcibiades was recalled to Athens for trial. Fearing that he would be unjustly condemned, Alcibiades defected to Sparta and Nicias was placed in charge of the mission. After his defection, Alcibiades claimed to the Spartans that the Athenians planned to use Sicily as a springboard for the conquest of all of Italy and Carthage, and to use the resources and soldiers from these new conquests to conquer the Peloponnese. +

The Athenian force consisted of over 100 ships and some 5,000 infantry and light-armored troops. Cavalry was limited to about 30 horses, which proved to be no match for the large and highly trained Syracusan cavalry. Upon landing in Sicily, several cities immediately joined the Athenian cause. Instead of attacking at once, Nicias procrastinated and the campaigning season of 415 BC ended with Syracuse scarcely damaged. With winter approaching, the Athenians were then forced to withdraw into their quarters, and they spent the winter gathering allies and preparing to destroy Syracuse. The delay allowed the Syracusans to send for help from Sparta, who sent their general Gylippus to Sicily with reinforcements. Upon arriving, he raised up a force from several Sicilian cities, and went to the relief of Syracuse. He took command of the Syracusan troops, and in a series of battles defeated the Athenian forces, and prevented them from invading the city. +

Nicias then sent word to Athens asking for reinforcements. Demosthenes was chosen and led another fleet to Sicily, joining his forces with those of Nicias. More battles ensued and again, the Syracusans and their allies defeated the Athenians. Demosthenes argued for a retreat to Athens, but Nicias at first refused. After additional setbacks, Nicias seemed to agree to a retreat until a bad omen, in the form of a lunar eclipse, delayed any withdrawal. The delay was costly and forced the Athenians into a major sea battle in the Great Harbor of Syracuse. The Athenians were thoroughly defeated. Nicias and Demosthenes marched their remaining forces inland in search of friendly allies. The Syracusan cavalry rode them down mercilessly, eventually killing or enslaving all who were left of the mighty Athenian fleet. +

After the Sicilian Expedition

During the disastrous Sicilian expeditions Athens needed the help of the islanders on Melos, who the Athenians had just ruthlessly slaughtered. The total defeat of the Athenian fulfilled a prediction by the Melians. “We know that in war fortune sometimes makes odds more level than could be expected.” Thucydides wrote, “They now suffered very nearly what they had inflicted, They had come to enslave others, and were departing in fear of being enslaved themselves.”

The Spartans were not content with simply sending aid to Sicily; they also resolved to take the war to the Athenians. Sparta counterattacked with soldiers in blood-red cloaks. The Spartans cut off Athens grain supply from Thrace and the Black Sea and laid siege to Athens: people starved, more fields were burned.

On the advice of Alcibiades, they fortified Decelea, near Athens, and prevented the Athenians from making use of their land year round. The fortification of Decelea prevented the shipment of supplies overland to Athens, and forced all supplies to be brought in by sea at increased expense. Perhaps worst of all, the nearby silver mines were totally disrupted, with as many as 20,000 Athenian slaves freed by the Spartan hoplites at Decelea. With the treasury and emergency reserve fund of 1,000 talents dwindling away, the Athenians were forced to demand even more tribute from her subject allies, further increasing tensions and the threat of further rebellion within the Empire. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Following the destruction of the Sicilian Expedition, Lacedaemon encouraged the revolt of Athens's tributary allies, and indeed, much of Ionia rose in revolt against Athens. The Syracusans sent their fleet to the Peloponnesians, and the Persians decided to support the Spartans with money and ships. Revolt and faction threatened in Athens itself. +

The Athenians managed to survive for several reasons. First, their foes were lacking in initiative. Corinth and Syracuse were slow to bring their fleets into the Aegean, and Sparta's other allies were also slow to furnish troops or ships. The Ionian states that rebelled expected protection, and many rejoined the Athenian side. The Persians were slow to furnish promised funds and ships, frustrating battle plans. Between 410 and 406, Athens won a continuous string of victories, and eventually recovered large portions of its empire. +

Athens Surrenders

Faction triumphed in Athens following a minor Spartan victory by their skillful general Lysander at the naval battle of Notium in 406 BC. Alcibiades was not re-elected general by the Athenians and he exiled himself from the city. He would never again lead Athenians in battle. Athens was then victorious at the naval battle of Arginusae. The Spartan fleet under Callicratidas lost 70 ships and the Athenians lost 25 ships. But, due to bad weather, the Athenians were unable to rescue their stranded crews or to finish off the Spartan fleet. Despite their victory, these failures caused outrage in Athens and led to a controversial trial. The trial resulted in the execution of six of Athens's top naval commanders. Athens's naval supremacy would now be challenged without several of its most able military leaders and a demoralized navy. +

Retreat of the Athenians from Syracuse

Unlike some of his predecessors the new Spartan general, Lysander, was not a member of the Spartan royal families and was also formidable in naval strategy; he was an artful diplomat, who had even cultivated good personal relationships with the Achaemenid prince Cyrus the Younger, son of Emperor Darius II. Seizing its opportunity, the Spartan fleet sailed at once to the Dardanelles, the source of Athens's grain. Threatened with starvation, the Athenian fleet had no choice but to follow. Through cunning strategy, Lysander totally defeated the Athenian fleet, in 405 BC, at the Battle of Aegospotami, destroying 168 ships and capturing some three or four thousand Athenian sailors. Only twelve Athenian ships escaped, and several of these sailed to Cyprus, carrying the strategos (general) Conon, who was anxious not to face the judgment of the Assembly. +

Facing starvation and disease from the prolonged siege, Athens surrendered in April 404 BC, and its allies soon surrendered as well. The democrats at Samos, loyal to the bitter last, held on slightly longer, and were allowed to flee with their lives. The surrender stripped Athens of its walls, its fleet, and all of its overseas possessions. Corinth and Thebes demanded that Athens should be destroyed and all its citizens should be enslaved. However, the Spartans announced their refusal to destroy a city that had done a good service at a time of greatest danger to Greece, and took Athens into their own system. Athens was "to have the same friends and enemies" as Sparta. +

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024