Home | Category: Greek Classical Age (500 B.C. to 323 B.C.) / Military

AFTER THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR

The decline of Greek civilization and the end of the Golden Age of Athens began in 404 B.C. with Sparta's victory over Athens in the Great Peloponnesian War. Although democracy was reestablished in Athens in the 4th century B.C. and Plato founded of the Academy in 387 B.C. and Aristotle founded the Lyceum in 335 B.C., the war left Greece bitterly divided and open to conquest from Macedonia.

The 27-year Peloponnesian War (431 B.C. to 404 B.C.) is named after the Peloponnesian League, an alliance led by Sparta that included Corinth and Thebes, that dominated the Peloponnesian peninsula . Sparta had traditionally been stronger militarily than Athens but Athens was stronger and richer as a result of tributes pouring in through the Delian League — an alliance that stretched across the Mediterranean. The resulting imbalance had much to do with the why the war was fought.

After Athens surrendered to Sparta, the Long Walls that surrounded Athens were torn down by the Spartans to music of flutes. Sparta installed despotic rulers but mercifully allowed Athens' people to live. Captured Athenian soldiers were put to work as slaves in Syracuse's stone quarries.

After the Peloponnesian Wars, Greek culture declined: ambition replaced honor, oratory skill became a method of furthering one’s career and attaining power, democratic institutions were undermined by corruption and citizens demanded “rights, not duties, and pleasure instead of work.”

Sparta remained the supreme power in Greece for about 30 years. Non-Spartan Greeks chafed under Spartan rule. There were rebellions and unrest and progressively fewer Spartan warrior to carry on the traditions. Finally when only a few hundred Spartan citizen-soldier remained the Thebans under Epaminodas defeated Sparta. Later it like the rest of Greece came under the control of Alexander the Great.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MAJOR EVENTS DURING THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR (431-404 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) and After, See Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University sourcebooks.web.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece” by Josiah Ober (2015) Amazon.com;

“Sparta: Fall of a Warrior Nation” by Philip Matyszak (2018) Amazon.com;

“Leuctra 371 BC: The Destruction of Spartan Dominance” by Murray Dahm and Seán Ó’Brógáin (2021) Amazon.com;

“Hellenica” by Xenophon (Landmark) Amazon.com;

“By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire” by Ian Worthington (2016) Amazon.com;

“Philip and Alexander: Kings and Conquerors” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Macedonian War Machine, 359–281 BC: Neglected Aspects of the Armies of Philip, Alexander and the Successors (359-281 BC)” by David Karunanithy (2020) Amazon.com;

“Roman Conquests: Macedonia and Greece” by Philip Matyszak (Author) Amazon.com;

“The Peloponnesian War” by Donald Kagan (2003) Amazon.com;

“A War Like No Other” by Victor Davis Hanson (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece” by Jennifer Roberts (2017) Amazon.com;

“Athens and Sparta: Constructing Greek Political and Social History from 478 BC” by Anton Powell (1988) Amazon.com;

“The Spartans: The World of the Warrior-Heroes of Ancient Greece, from Utopia to Crisis and Collapse” by Paul Cartledge (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Athens” by Plutarch (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Athenian Empire” by Russell Meiggs (1972) Amazon.com;

“A Chronology of Ancient Greece” by Timothy Venning (2015) Amazon.com;

“Warfare in the Classical World” by John Warry, illustrated (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Wars of the Ancient Greeks” by Victor Davis Hanson (1999) Amazon.com;

Battle of Leuctra (371 B.C.): Spartans Downfall Described by Xenophon

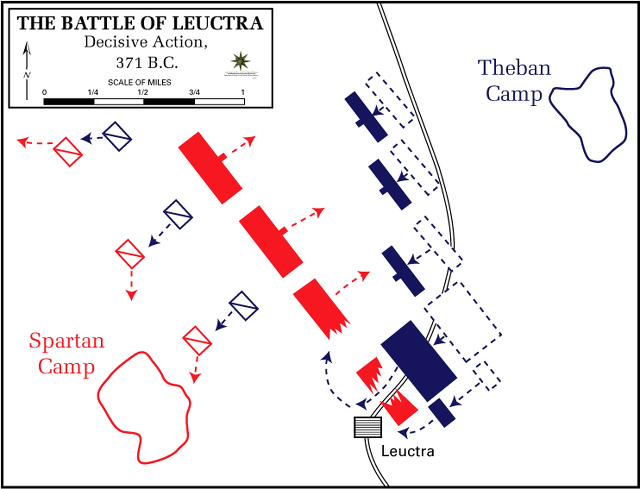

In 371 B.C., the Spartans suffered a disastrous defeat to the Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra, in Boeotia, on the road from Plataea to Thespiae, The Spartans never recovered from the blow this disaster gave to their prestige. It was poetic justice that this punishment for their ill rule should come from Thebes — the city they had used shamefully beyond all others. The credit for the victory falls to Epaminondas, though he is not named by the historian Xenophon (died 354 B.C.), who was a great admirer of the Spartans and did not to glorify their most formidable enemy.

Xenophon wrote in Hellenica, Book VI, Chap. IV: “When the Spartan king [Cleombrotus] observed that the Thebans, so far from giving autonomy to the Boeotian city states [as demanded], were not even disbanding their army and had clearly the purpose of fighting a general engagement, he felt justified in marching his troops into Boeotia [from Phocis where he had been]. The point of ingress which he adopted was not that which the Thebans expected from Phocis, and where they were keeping a guard at a defile, but marching through Thisbae, by a hilly and unsuspected route, he arrived before Creusis, taking that fortress and twelve Theban war ships to boot. After this, he advanced from the seaboard, and encamped in Leuctra in Thespian territory. The Thebans encamped on a rising ground immediately opposite at no great distance, and were supported by no allies, save their [fellow] Boeotians. [Source: William Stearns Davis, “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols., (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. I: Greece and the East, pp. 279-284]

“At this juncture the friends of Cleombrotus came to him and urged upon him strong reasons for delivering battle. "If you let the Thebans escape without fighting," they said, "you will run great risks of suffering the extreme penalty at the hands of the state....In times past you have missed doing anything notable, and let good chances slip. If you have any care for yourself, or any attachment to your fatherland, march you must against the enemy." Thus spoke his friends, and his enemies remarked, "Now our fine fellow will show whether he is really so partial to the Thebans as is alleged."

“With these words ringing in his ears, Cleombrotus felt driven to join battle. On their side the Theban leaders calculated that if they did not fight, their provincial cities would hold aloof from them, and Thebes itself would be besieged; while if the populace of Thebes failed to get provisions there was a good chance the city itself would turn against [its own leaders]; and seeing that many of them had already tasted the bitterness of exile, they concluded it were better to die on the battlefield than renew the exile's life. Besides this, they were somewhat encouraged by an oracle, predicting that "the Lacedaemonians would be defeated on the spot where stood the monument of the maidens," — who, as the story goes, being outraged by certain Lacedaemonians, had slain themselves. This sepulchral monument the Thebans decked with ornaments before the battle. Furthermore, tidings were brought from the city that all the temples had opened of their own accord; and the priestesses asserted that the gods foretold victory. Cleombrotus held his last council "whether to fight or not" after the morning meal. In the heat of noon a little wine goes a long way; and people said it took a somewhat provocative effect upon their spirits.

“Both sides were now arming, and there were unmistakable signs of approaching battle, when, as the first incident, there issued from the Boeotian lines a long train bent on departure — they were furnishers of the market, a detachment of baggage bearers and in general such people as had no hankering to join in the fight. [A band of the Spartan allies headed them off, and drove them back to the Boeotian camp . . . ] the result being to make the Boeotian army more numerous and closely packed than before. The next move was as a result of the open plain between the two armies — the Lacedaemonians posted their cavalry in front of their squares of infantry, and the Thebans imitated them. Only there was this difference — the Theban horse were in a high state of training and efficiency, thanks to their war with the Orchomenians, and also their war with Thespiae; the Lacedaemonian cavalry was at its very worst just now. The horses were reared and kept by the richest citizens; but whenever the levy was called out, a trooper appeared who took the horse with any sort of arms that might be presented to him, and set off on an expedition at a moment's notice. These troopers, too, were the least able-bodied of the men — just raw recruits simply set astride their horses, and wanting in all soldierly ambition. Such was the cavalry of either antagonist.

“The heavy infantry of the Lacedaemonians, it is said, advanced by sections three abreast, allowing a total depth to the whole line of not more than twelve. The Thebans were formed in close order of not less than fifty shields deep, calculating that victory over the [Spartan] king's division of his army would involve the easy conquest of the rest.

“Cleombrotus had hardly begun to lead his division against the foe, when, before in fact the troops with him were aware of his advance, the cavalry had already come into collision, and that of the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) was speedily worsted. In their flight they became involved with their own heavy infantry; and, to make matters worse, the Theban regiments were already attacking vigorously. Still strong evidence exists for supposing that Cleombrotus and his division were, in the first instance, victorious in the battle, if we consider the fact that they could never have picked him up and brought him back alive unless his vanguard had been masters of the situation for the moment.

“When, however, Deinon the polemarch, and Sphodrias, a member of the king's council, with his son Cleonymus, had fallen, then it was that the cavalry and the polemarch's adjutants, as they are called, with the rest, under pressure of the mass against them, began retreating. And the left wing of the Lacedaemonians, seeing the right borne down in this way, also swerved. Still, in spite of the numbers slain, and broken as they were, as soon as they had crossed the trench which protected their camp in front, they grounded arms on the spot whence they had rushed to battle. This camp, it should be borne in mind, did not lie on the level, but was pitched on a somewhat steep incline.

“At this juncture there were some Lacedaemonians, who, looking upon such a disaster as intolerable, maintained that they ought to prevent the enemy from erecting atrophy, and try to recover the dead, not under a flag of truce, but by another battle. The polemarchs, however, seeing that nearly 1000 of the total Lacedaemonian troops were slain, and seeing, too, that of the 700 regular Spartans who were on the field some 400 lay dead; aware likewise of the despondency which reigned among the allies, and the general disinclination on their part to fight longer — a frame of mind not far from positive satisfaction in some cases at what had happened — under the circumstances, I say, the polemarchs called a council of the ablest representatives of the shattered army, and deliberated on what should be done. Finally, the unanimous opinion was to pick up the dead under a flag of truce, and they sent a herald to treat for terms. The Thebans after that set up a trophy, and gave back the bodies under a truce.

Decline of Sparta After The Battle Leuctra

Xenophon wrote in Hellenica, Book VI, Chap. IV: “After these events a messenger was dispatched to Lacedaemon (Sparta) with news of the calamity. He reached his destination on the last day of the gymnopaediae [midsummer festival] just when the chorus of grown men had entered the theater. The ephors heard the mournful tidings not without grief or pain, as needs they must, I take it; but for all that they did not dismiss the chorus, but allowed the contest to run out its natural course. What they did was to deliver the names of those who had fallen to their friends and families, with a word of warning to the women not to make any loud lamentation, but to bear their sorrow in silence; and the next day it was a striking spectacle to see those who had relations among the slain moving to and fro in public with bright and radiant looks, whilst of those whose friends were reported to be living, barely a man was seen, and these flitted by with lowered heads and scowling brows, as if in humiliation. [Source: William Stearns Davis, “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols., (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. I: Greece and the East, pp. 279-284]

After this, Elis and the Arcadian states seized the opportunity to throw off the yoke of Spartan hegemony. The Peloponnesian League was then further reduced by the Theban liberation of Messenia from Spartan control in 369 BC. The states of the north-eastern Peloponnese, including Corinth, Sicyon and Epidauros remained loyal to Sparta, but as the war wore on in the 360s B.C., many joined the Thebans or took a neutral position, though Elis and some of the Arcadian states realigned themselves with Sparta. In 338 BC, the Peloponnesian League was disbanded when Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, formed the League of Corinth after defeating Thebes and Athens, incorporating all the Peloponnesian states except Sparta. [Source: Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica]

Rise of Macedon Under Philip II

Philip II of Macedon (ruled 359-336 B.C.) was the father of Alexander the Great. Most of Philip's tenure as king was spent consolidating his empire in Macedonia and extending it southward into Greece. He forged his kingdom by winning crucial battles and forming important alliances through his marriages. He increased the wealth and status through trade and diplomacy at a time when Macedonia was regarded by other Greek city states such as Athens and Thebes as a barbarian territory even though the Macedonians spoke Greek and considered themselves Greeks.

Philip II took control of Thrace and Thessaly and declared war on Athens and Thebes and their allies. In August 338 B.C., at the Battle of Chaeronea, Macedonia defeated Athens and Philip became the de facto ruler of Greece. He never conquered Athens but formed an alliance with the city after the battle.

Philip II's ambition after the victory was to attack Persia, the arch enemy of Greece. In 336 B.C. he began a campaign against the Persians by sending an advance of 10,000 men to Asia Minor. He wasn't with the army because he had to be at the wedding one of his daughters and was murdered there..

Expansion of Macedon

Battle of Chaeronea, 338 B.C.: Philip of Macedon Defeats the Greeks

In 338 B.C. at the Battle of Chaeronea, in Chaeronea in Boeotia, Philip II of Macedon defeated an alliance of Greek city-states led by Athens and Thebes. The battle was the culmination of Philip's campaign in Greece (339–338 BC) and marked the end of the Greek system of city-states and the replacement by large military monarchies. On the battle Diodorus Siculus (90-30 B.C.) wrote in “Library of History, Book XVI, Chap. 14: “In the year Charondas was first archon in Athens, Philip, King of Macedon, being already in alliance with many of the Greeks, made it his chief business to subdue the Athenians, and thereby with more ease control all Hellas. To this end he presently seized Elateia [a Phocian town commanding the mountain passes southward], in order to fall on the Athenians, imagining to overcome them with ease; since he conceived they were not at all ready for war, having so lately made peace with him. Upon the taking of Elateia, messengers hastened by night to Athens, informing the Athenians that the place was taken, and Philip was leading on his men in full force to invade Attica. [Source: William Stearns Davis,”Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols., (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-1913), Vol. I: Greece and the East, pp. 293-296]

“At length the hosts engaged, and the battle was fierce and bloody. It continued long with fearful slaughter, but victory was uncertain, until Alexander, anxious to give his father proof of his valor---and followed by a courageous band---was the first to break through the main body of the enemy, directly opposing him, slaying many; and bore down all before him---and his men, pressing on closely, cut to pieces the lines of the enemy; and after the ground had been piled with the dead, put the wing resisting him in flight. The king, too, at the head of his corps, fought with no less boldness and fury, that the glory of victory might not be attributed to his son. He forced the enemy resisting him also to give ground, and at length completely routed them, and so was the chief instrument of the victory.

“Over one thousand Athenians fell, and two thousand were made prisoners. A great number of Boeotians, too, perished, and many more were captured by the enemy. . . [After some boastful conduct by the king, thanks to the influence of Demades, an Athenian orator who had been captured], Philip sent ambassadors to Athens and renewed the peace with her [on very tolerable terms, leaving her most of her local liberties]. He also made peace with the Boeotians, but placed a garrison in Thebes. Having thus struck terror into the leading Greek states, he made it his chief effort to be chosen generalissimo of Greece. It being noised abroad that he would make war upon the Persians, on behalf of the Greeks, in order to avenge the impieties committed by them against the Greek gods, he presently won public favor over to his side throughout Greece. He was very liberal and courteous, also, to both private citizens and communities, and proclaimed to the cities that he wished to consult with them as to the common good.' Whereupon a general council [of the Greek cities] was convened at Corinth, where he declared his design of making war on the Persians, and the reasons he hoped for success; and therefore desired the Council to join him as allies in the war. At length he was created general of all Greece, with absolute power, and having made mighty preparations and assigned the contingents to be sent by each city, he returned to Macedonia [where, soon after, he was murdered by Pausanius, a private enemy].”

See Separate Article: PHILIP II (ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S FATHER): HIS LIFE, LOVES, MURDER AND THE RISE OF MACEDON europe.factsanddetails.com

End and Legacy of Classical Greece

Weakened by feuds between rival city states and threat from Carthage and Rome, the Greek colonies eventually were conquered by the Romans around 210 B.C., but Greek cultures, customs and language lasted for centuries more. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, most people in Naples still spoke Greek as their first language.

In 146 B.C. the Romans destroyed Carthage and Corinth, the home of the last Greek league of cities that had tried to resist Roman expansion. Under the command of Roman consul Lucius Mummius Corinthian men were slaughtered, women and children were sold into slavery, art was shipped back to Rome and Corinth was turned into a ghost town.

Ancient Greece is still very close to use today. Many of are buildings are constructed to look like Greek temples, our coins have changed little in design since Greek coins, our comedies are based as many of the same kind of jokes used in Greek plays and some of our greatest sporting events are modeled on ancient Greek games. [Source: "History of Art" by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.]

People on the isolated village of Ólimbos speak a Greek dialect that is so old some of the words date back to Homer's time. Their musical instruments include goatskin bagpipes and the three stringed lyre. The tools they use to cultivate wheat and barley are the same as those used by the Byzantines.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024