Home | Category: Culture and Sports

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS

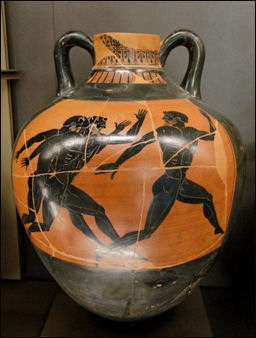

Panathenaic amphora Kleophrades In addition to the ancient Olympics in the Peloponnesos region of Greece, there were similar sporting competitions held all over Greece and Asia Minor. These included the Nemean Games, Delphi Games, Isthmia Games held near Corinth and the Panathenaea at Athens. They were all founded in the 6th century B.C.

The Nemean games took place every year and were most similar to the Olympics. The Pythian games were held every four years at Delphi to honor Apollo, and the Nemean games and Ishmian games were held every two years. All these games were scheduled so that there were at least one or two events every year and together they were known as the circuit. Athletes came from as far away as France and Syria to compete and traveled a circuit not unlike the golf or tennis tours of today.

The Pythians did not begin to calculate by their games till the year 586 B.C., the Isthmians in 582 B.C. , and the Nemeans in 573 B.C. . The Olympic festivals always took place at the first full moon of the summer solstice, the Pythian in the autumn of the third year of an Olympiad; we cannot determine the exact period of the others, and only know that the Isthmian games were held at midsummer, and the Nemean alternately in winter and in summer. The main features of all, next to the usual acts of worship, such as prayer, sacrifices, etc., was the athletic contests connected with them. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

All four had attained so great a reputation even beyond the frontiers of their narrow home that most of the Greek states took part in them by means of official embassies (θεωρίαι) and numbers of spectators came from a distance, and a great market was held there in consequence. This universal interest taken in the festivals gave them a character of inviolability, so that they were able to continue even in time of war, since there was always a truce as long as the games lasted, and all who took part in them were allowed to travel undisturbed, as soon as the heralds of peace had announced the beginning of the sacred month, first in their own state, and afterwards in that of all the Greeks who took part in the contests.

In addition to the games at Delphi, Olympia, Nemea and Isthmia, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ many local games, such as the Panathenaic games at Athens, were modeled on these four periodoi, or circuit games. The Pythian games at Delphi honored Apollo and included singing and drama contests; at Nemea, games were held in honor of Zeus; at Isthmia, they were celebrated for Poseidon; and at Olympia, they were dedicated to Zeus, although separate games in which young, unmarried women competed were celebrated for Hera. The victors at all these games brought honor to themselves, their families, and their hometowns. Public honors were bestowed on them, statues were dedicated to them, and victory poems were written to commemorate their feats. Numerous vases are decorated with scenes of competitions and the odes of Pindar celebrate a number of athletic victories. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK OLYMPICS: WHAT THEY WERE LIKE, ATMOSPHERE, PURPOSE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES: TRAINING, NUDITY, WINNERS AND CHEATERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

See Delphic Festival and Pythian Games Under ORACLE IN DELPHI: PYTHIA, TEMPLE, VAPORS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

Features of Ancient Greek Sports Festivals

The value of the prizes given for athletic skill varied greatly, from the wreath of olive at Olympia and the parsley leaves of Nemea to articles of considerable value and, in a few cases, even money. At the Panathenaea the prizes were jars of oil in greater or less numbers, and the painted vases known as Panathenaic amphorai. Probably only one of these was given to a victor. They bear on one side a picture of the contest in which the vase was won, and on the other, the figure of Athena with an inscription, “From the games at Athens”. When the prize took the form of a wreath, the victor first bound a fillet or band of wool around his head and upon this the official in charge of the games placed the wreath. The act of tying the fillet was often represented by Greek sculptors; the most famous example is, of course, the Polykleitan statue known as the Diadoumenos. On one psykter a boy holds in his hands the palms signifying victory is being crowned by an official. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

The victors at all these games brought honor to themselves, their families, and their hometowns and were awarded different plants. . Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece” (c. A.D. 175): “A crown of wild olive was given to the victor at Olympia, and laurel at Delphi. And at the Isthmian Games pine leaves, at the Nemean Games parsley, as we know from the cases of Palaemon and Archemorus. But most games have a crown of palm as the prize, and everywhere the palm is put into the right hand of the victor.” [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Sometimes music and poetry contests were staged in conjunction with Olympic-style athletic competitions. Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “There was anciently a contest held at Delphi, of players on the cithara, who executed a paean in honor of the god. It was instituted by the Delphians. But after the Crisaean war the amphictyons, in the time of Eurylochus, established contests for horses and gymnastic sports, in which the victor was crowned. These were called Pythian games, in addition to the musical contests.” [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 47-53]

Delphic Festival and Pythian Games

The games performed at Delphi in honor of Pythian Apollo bore the name of the Great Pythia, to distinguish them from the Lesser Pythia, held every year at Delphi, and also from the festival of the same name celebrated in other places. This festival, which at first was held every eight years, had been changed to a quadrennial one after the beginning of the 6th century B.C.; it lasted several days, and gradually many additions were made to the original contests. At first the musical competition, which comprised kithara and flute playing, was the only one; in later times, too, it was the principal part of the festival, but after the example of the Olympian games, gymnastic and equestrian contests were also added. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We know but little of the athletic contests which gradually found a place in the Pythian games. In essentials they were the same as those at Olympia, but the double course and the long course for boys were also added, while at Olympia these two contests were only open to men. The order of events, too, was different; the competitors were classed according to age, and each class, after completing its own contests, was able to rest while the others went through the same exercise, so that these intervals for rest enabled the boys to perform greater feats of running than they could at Olympia, where they had to enter for all their contests before the men’s turn came at all.

To the usual gymnastic sports were afterwards added the race in full panoply and the pancration for boys. Equestrian competitions were early introduced; racing with full-grown horses, with four-horse chariots, and afterwards with two-horse chariots; when colts were introduced at Olympia the example was also followed at Delphi: probably the events followed in such a way that the musical contest was connected with the acts of worship, and was followed by the gymnastic, and this by the equestrian contests. The gymnastic sports were held, at the time of Pindar, in the neighbourhood of the ruined city Cirrha, south of the mouth of the Pleistos; afterwards the Delphic Stadion was to the north-west of the city, while the driving and riding races took place in the old Stadion near the ruined city of Cirrha. In later times there was also a theatre for the performance of the musical contests.

See Delphic Festival and Pythian Games Under ORACLE IN DELPHI: PYTHIA, TEMPLE, VAPORS europe.factsanddetails.com

Isthmian Games

The Isthmian games, the third of the great Hellenic national festivals, were celebrated on the isthmus of Corinth, in the sacred pine grove of Poseidon, where a hippodrome and a stadion for equestrian and athletic contests had been erected. The festival, which from the year 582 B.C. onwards, became national and Hellenic, took place every two years, in the first and third years of an Olympiad; it consisted of musical, gymnastic, and equestrian contests.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We do not hear of any differences between these games and those at Olympia, and we may assume that there were the usual competitions for men and boys; in addition to them there was an intermediate class of the beardless ones — that is, youths. Of course, there was a universal truce during the Isthmian games, and numerous and splendid embassies attended it, since the site between two seas facilitated attendance.

The arrangement of the programme fell to the Corinthians, who also appointed the umpires, probably from among the rich and respected citizens. The prize of victory was a wreath of ivy, for which they afterwards substituted one of pine, and this seems to have been still the custom at the time of Ibycus, who, as Schiller tells us, met his death on the way to this “contest of chariots and song.” In the later period, especially in the Hellenistic and Roman times, there were also rhetorical and poetical recitations at the Isthmian games, but they did not form a part of the musical contest.

Nemean Games

The Nemean games were held at Argolis, in a valley between Cleonae and Phlius, in a grove belonging to the sanctuary of Zeus-Nemeios, and they did not attain national importance till the year 573. These, like the Isthmian games, were held every two years, in the second and fourth years of an Olympiad. The contests here also comprised musical, gymnastic, and equestrian competitions; we are incidentally informed that kithara and flute players appeared in the musical contest. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We have no information about the length of its duration, but it must certainly have lasted for several days. The Cleonaeans were for a long time superintendents and umpires, but when the Argives gained possession of the Nemean sanctuary they also claimed this privilege. The prize of victory here, as at the Isthmian games, was a wreath of ivy; there were the same arrangements for a universal truce, and visits of sacred envoys, as at other great festivals.

The American archaeologist named Stephen Miller, resurrected the Nemea Games in the ancient stadium in Nemea. Nemea is 80 miles south of Athens in the Peloponnesus. Athletes competed almost as they would have in ancient times: they competed barefoot but not in the nude and women were allowed to compete. Some from 500 runners from 28 countries competed in events like the “stadion” dash (89 meters) and the 7.5-kilometer Footsteps of Herakeles race. The winner was crowned with a ring of wild celery taken from a stream near the stadium.

Sports Contests at the Panathenaea

Panathinaiko The greatest festival of the Athenians, the Panathenaea, was celebrated in the first month of the Athenian calendar, Hekatombaeon (probably our July). The athletic contests were arranged according to age (boys, youths, men); the youngest entered first, and each class ended its competitions before the next one began. Similarly the competitions advanced from easy to difficult; they were of the usual kinds already described, but it was only the men from whom all were required. Boys and youths in the earliest period entered for racing, wrestling, and boxing, pancration, and pentathlon. Afterwards the pentathlon was abandoned, and the double and long course introduced instead, though probably the requirements for these were reduced, since the usual attainments of these contests would have been too great for boys. We do not know exactly where the gymnastic competitions took place, since the Panathenaeic Stadion was not built till the latter half of the fourth century. Before that there seems to have been a place to the west of the Peiraeus, where both equestrian and athletic contests were carried on; here, too, the victors were proclaimed, and the prizes conferred on them. These consisted in a quantity of oil from the celebrated olive-trees of Athene in the Academy, and this was drawn into earthen amphoras, on one side of which was represented the image of the patron goddess, and on the other generally a scene from the gymnastic competition. Many imitations of these amphoras exist, and no small number of them have come down to us, and are known as Panathenaeic prize amphoras.

There were several events peculiar to the equestrian contests at Athens. Thus, in Attica and Boeotia chariot-jumping was a popular sport. Besides the charioteer on the two-wheeled car there was a second person, who, while the chariot was moving at full speed, jumped down from the car and up again, assisted by the charioteer; this performance is traced back by legend to the time of Erichthonius. There were also martial contests, in which warriors in full panoply stood in their chariots; and also races of javelin-throwers, who aimed at a fixed goal from their running horses; but these sports connected with the Panathenaea are known to us only by casual allusions, and not by accurate description. Here, as elsewhere, we learn from the inscriptions that the usual kinds of racing took place, namely, with four horses, and afterwards, too, with colts, as well as riding races. Here, as in the athletic contests, the prize consisted in jars of oil; in both cases the first prize was generally five times the value of the second.

Instead of a gold medal, victors at the ancient Greek Panathenaic Games received amphora (terra-cotta pots) emblazoned with their specific sport and filled with Athenian olive oil from sacred trees, a highly "valuable prize," according to Harvard Art Museums. One such amphora, dated to 530 B.C., was found in Vulci, Italy. According to Live Science: This particular amphora features a lineup of five runners during a footrace, a competition considered the "earliest known event in the Panathenaic Games." Athletes competed fully naked, since they thought their physiques might intimidate their competition.

The pot, which stands 62 centimeters (24.5 inches) tall, is attributed to "Euphiletos Painter." This anonymous artist was known for an art style called black-figure pottery, in which subjects were drawn in silhouette, according to the British Museum. This is just one of the many vases awarded to the victors at the Games, with other pots featuring charioteers, archers and boxers. In general, ancient Greeks considered olive trees "sacred," and they symbolized Zeus, the god of the sky and, later, the god of the Olympics, according to the Journal of Olympic History. [Source Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, July 26, 2024]

See Separate Article: FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Hera Games, Ancient Olympic of Women

Stephen Instone wrote for the BBC: “Women did not participate at the main Olympic festival. They had their own Games, in honour of Hera, where the sole event was a run of five-sixths of the length of the stadium - which would have preserved in male opinion the inferior status of women. Whether women could even watch the festival is disputed. Unmarried virgins, not soiled by sex or motherhood and thus maintaining the religious purity of the occasion, probably could. Festivals (and, for example, funerals) were among the limited occasions when women, especially virgins, or parthenoi, had a public role. At the Games unmarried girls, besides helping with the running of the festival, may have taken the opportunity to find a fit future husband. As Pindar wrote, about a victor in the Greek colony of Cyrene: “'When they saw you many times victorious in the Games of Athene, each of the maidens was speechless as they prayed you might be her husband or son.” [Source: Stephen Instone, BBC, February 17, 2011|::|]

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece” (c. A.D. 175): As you go from Scillus along the road to Olympia, before you cross the Alpheius, there is a mountain with high, precipitous cliffs. It is called Mount Typaeum. It is a law of Elis to cast down it any women who are caught present at the Olympic games, or even on the other side of the Alpheius, on the days prohibited to women. However, they say that no woman has been caught, except Callipateira only....She, being a widow, disguised herself exactly like a gymnastic trainer, and brought her son to compete at Olympia. Peisirodus, for so her son was called, was victorious, and Callipateira, as she was jumping over the enclosure in which they keep the trainers shut up, bared her person. So her sex was discovered, but they let her go unpunished out of respect for her father, her brothers and her son, all of whom had been victorious at Olympia. But a law was passed that for the future trainers should strip before entering the arena. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“Every fourth year there is woven for Hera a robe by the Sixteen Women [Source: Elis], and the same also hold games called Heraea. The games consist of foot-races for maidens. These are not all of the same age. The first to run are the youngest; after them come the next in age, and the last to run are the oldest of the maidens. They run in the following way: their hair hangs down, a tunic reaches to a little above the knee, and they bare the right shoulder as far as the breast. These too have the Olympic stadium reserved for their games, but the course of the stadium is shortened for them by about one-sixth of its length.

“To the winning maidens they give crowns of olive and a portion of the cow sacrificed to Hera. They may also dedicate statues with their names inscribed upon them. The games of the maidens too are traced back to ancient times; they say that, out of gratitude to Hera for her marriage with Pelops, Hippodameia assembled the Sixteen Women, and with them inaugurated the Heraea. The Sixteen Women also arrange two choral dances, one called that of Physcoa and the other that of Hippodameia.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024