ORACLE OF DELPHI

Oracle of Delphi

The Oracle at Delphi was a female oracle who worked out of the Temple of Apollo at the ancient site of Delphi. She was required to be a virgin over the age of 50 but dressed as a maiden. When she performed her prophecies, she drank from a sacred spring, enveloped by vapors, and then returned to a basement in the temple, where she sat on a three-legged stool and chewed sacred laurel leaves. She received her messages from a mythical snake and chanted in a language that was interpreted by a priest and believed to be the words of the god Apollo.

Jean-Pierre Isbouts wrote in National Geographic History: In ancient Greece, citizens who had a burning question could seek the gods’ wisdom through oracles — and there was no more influential oracle than the one at Delphi. Reaching its peak influence between the 8th and 6th centuries B.C., this massive temple dedicated to the god Apollo stood at the heart of the Delphi sanctuary that, on most days, served as a place of worship. But for nine days a year, the temple became an oracle when a special medium, called the Pythia, received a select group of visitors (who had made a sizeable donation for the privilege).

The oracles had a reputation for saying what their customers wanted to hear. The scholar Michael Grants wrote that he Oracle's prophecies were conservative and flexible. "Some have...preferred to ascribe the entire phenomenon to clever stage management, aided by an effective information system," he said. .Xenophobe reportedly ignored the advice of the Oracle of Delphi and took his troops deep into Persian territory, where they were trapped and massacred.

See Separate Article: ORACLES IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oracle: Ancient Delphi and the Science Behind Its Lost Secrets” by William J. Broad (2007) Amazon.com;

“Delphi: A History of the Center of the Ancient World” by Michael Scott (2015) Amazon.com;

“Revisiting Delphi: Religion and Storytelling in Ancient Greece” by Julia Kindt (2016) Amazon.com;

“Classical Athens and the Delphic Oracle: Divination and Democracy” by Hugh Bowden (2005) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Divination” by Sarah Iles Johnston (2008) Amazon.com;

“Omens and Oracles: Divination in Ancient Greece” by Matthew Dillon (2017) Amazon.com;

“Greek Divination And Magic With The Acceptance Of Omens” by W R Halliday (1886-1966) Amazon.com;

“Magic in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Lindsay C. Watson Amazon.com;

“Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion” by Christopher A. Faraone and Dirk Obbink (1997) Amazon.com;

"Magic, Witchcraft and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook

by Daniel Ogden | Apr 24, 2009 Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Necromancy” by Daniel Ogden (2004) Amazon.com;

“Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: a Collection of Ancient Texts” by Georg Luck (1985) Amazon.com;

“Superstitious Beliefs And Practices Of The Greeks And Romans” by William Reginald Halliday (1886-1966) Amazon.com;

“Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World” by John G. Gager (1999) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

Delphi

Delphi of oracle and Oedipus Rex fame was a real place where people went to have their fortunes told during a sacred ceremony. Delphi is located about 200 kilometers (120) miles from Athens

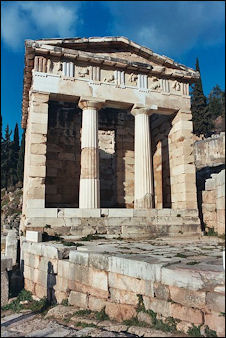

.png) The temple of Delphi, where the oracle did her magic, was on the slope of 2000-foot-high Mt. Parnassus at a place described as the navel of the Earth and the place where the gods descended to earth. Delphi is believed to have been a sacred spot as far back as 1500 B.C. and taken over by the Greeks around 1000 B.C.

The temple of Delphi, where the oracle did her magic, was on the slope of 2000-foot-high Mt. Parnassus at a place described as the navel of the Earth and the place where the gods descended to earth. Delphi is believed to have been a sacred spot as far back as 1500 B.C. and taken over by the Greeks around 1000 B.C.

Delphi was originally an oracle of an earth-mother goddess that was later taken over by Apollo. Alexander the Great and other leaders and influential people came from all over the Mediterranean, including Egypt, to Delphi for advice on politics. Slaves came to find out how they could please their masters. Parents inquired how they could cure their sons of love sickness and husbands wanted to find who was the father of their children.

Delphi became so popular that a large number of lodging houses and new houses opened up. The oracle was showered with gifts of silver and gold and became quite a wealthy woman. She stayed in business from 700 B.C. to 300 A.D. Delphi stopped functioning around the time of Rome became Christianized. Nero reportedly carted 500 statues from the site. It was officially shut down by Emperor Theodosius (379-95).

Myths and Legends About Delphi

According to legend, Delphi was originally an oracle of an earth-mother goddess. It was later taken over by Apollo after he slew a she-dragon, named Python, who lived in a cave on Mt. Parnassus.

María Teresa Magadán wrote in National Geographic History: Greek myth holds that the thunder god Zeus once dispatched two eagles flying in opposite directions across the sky. Where their paths crossed would be the center of the world. Legend says that the birds met over Delphi, seated on the slopes of Parnassós. Zeus marked the spot with a stone called the omphalos (navel), to signify the location’s centrality. [Source: María Teresa Magadán, National Geographic History, March 12, 2019]

According to another myth, this impressive spot in central Greece (about 100 miles northwest of Athens) was originally sacred to Gaea, mother goddess of the earth, who placed her son Python, a serpent, as a guard for Delphi and its oracle. Apollo, god of light and music, slew the serpent and took over the site for himself. Priestesses who served Apollo there were called the “Pythia,” named in honor of Gaea’s vanquished son. Throughout the classical world spread the belief that these priestesses channeled prophecies from Apollo himself.

History of Delphi

María Teresa Magadán wrote in National Geographic History: The cult of Apollo seems to have been functioning in Delphi as early as the eighth century B.C. About two centuries later, leaders from all over Greece were consulting the oracle on major issues of the day: waging war, founding colonies, and religious rituals. Since it was a place used by different — and often rival — Greek states, Delphi soon became not only a sacred space but also a place where a city-state could exhibit its status to the wider Greek world. [Source: María Teresa Magadán, National Geographic History, March 12, 2019]

Naval of the world If a particular city wanted to flaunt its success in war or trade, it could build a commemorative monument at Delphi. This practice led to an astonishing accumulation of monuments and sculptures at Delphi. Each piece serves as a visual guide to the power shifts in the region. Athenians, Spartans, Macedonians, and Romans all poured their wealth into making the “center of the world” reflect their glory. Delphi also hosted athletic, poetry, and music competitions. It was the venue for the Pythian Games, held every four years, second only to the ones held in Olympia.

Despite its status as a sacred site, Delphi was an attractive target for pillaging. An attack by the Persians came in 480 B.C., and one by the Gauls followed in 279 B.C. Rome took over Delphi in 191 B.C., but allowed the religious rituals and athletic competitions to continue. Things changed when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in A.D. 380. [Source: María Teresa Magadán, National Geographic History, March 12, 2019]

Between 391 and 392 Emperor Theodosius I banned pagan practices and closed Greek temples, including those at Delphi. With its religious function stripped away, the site fell into decay. A small settlement took root at the site and grew into the village of Kastri. Visitors were very rare in the centuries that followed. In 1436 an Italian merchant, Cyriacus of Ancona, made the arduous journey to Delphi, with his notes revealing what was left of the stadium and the theater, a round building he mistook for the Temple of Apollo, with some of its statues still standing. Greece became a part of the Ottoman Empire in 1453, which postponed Cyriacus’s idea to “restore antiquity, or redeem it from extinction.” The former center of the world would remain in obscurity for roughly 400 years.

Delphi Archaeological Site

The Delphi ruins are beautifully situated on the southern flank of Mt. Parnassos which also offers panoramic views of the valleys below. The center of the sanctuary where the ceremonies were held is dominated by the Temple of Apollo which is composed of a platform with several columns sticking up from it. Next to the temple is fountain of water where the oracle would wash her hands before she touched the "sacred stone." Leading to the temple is the "sacred way" which used to be lined with treasurers, offerings and arcades. Northwest of the temple is the 5000-seat theater where ancient Delphic drama festivals were held every four years and up a hill from there is the stadium where the Pythian games were held which included competitions among philosophers as well as sporting events.

According to UNESCO: “The pan-Hellenic sanctuary of Delphi, where the oracle of Apollo spoke, was the site of the omphalos, the 'navel of the world'. Blending harmoniously with the superb landscape and charged with sacred meaning, Delphi in the 6th century B.C. was indeed the religious centre and symbol of unity of the ancient Greek world. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“Delphi lies between two towering rocks of Mt. Parnassus, known as the Phaidriades (Shining) Rocks, in the Regional unit of Phocis in Central Greece. Here lies the Pan-Hellenic sanctuary of Apollo, the Olympian god of light, knowledge and harmony. The area was inhabited in the 2nd millennium B.C. as is evident from Mycenaean remains (1500-1100 B.C.). The development of the sanctuary and oracle began in the 8th century B.C. and their religious and political influence over the whole of Greece increased in the 6th century B.C. . At the same time, their fame and prestige spread throughout the whole of the then known world, from which pilgrims came to the site to receive an oracle from the Pythia, the priestess of Apollo. =

Oracle of Delphi entranced

“A place with a rich intangible heritage, Delphi was the centre of the world (omphalos) in the eyes of the ancient Greeks: according to myth, it was the meeting point of two eagles released by Zeus, one to the East and one in the West. The magnificent monumental complex is a human-made environment in perfect harmony with the rare natural environment, the principal features of which gave rise to the organisation of the cults. This harmonious relationship, which has remained undisturbed from ancient times to the present day, makes Delphi a unique monument and a priceless legacy bequeathed by the ancient Greek world to following generations. =

“The layout of Delphi is a unique artistic achievement. Mt. Parnassus is a veritable masterpiece and is where a series of monuments were built whose modular elements – terraces, temples, treasuries, etc. – combine to form a strong expression of the physical and moral values of a site which may be described as magical. Delphi had an immense impact throughout the ancient world, as can be ascertained by the various offerings of kings, dynasts, city-states and historical figures, who deemed that sending a valuable gift to the sanctuary, would ensure the favour of the god. The Sanctuary at Delphi, the object of great generosity and the crossroads of a wide variety of influences, was in turn imitated throughout the ancient world. Its influence extended as far as Bactria, following the conquest of Asia by Alexander the Great. Even pillaging of the Sanctuary by the emperor Nero and by Constantine the Great, who transported spoils from it to Rome and Constantinople, added to the artistic influence of Delphi. =

“Delphi bears a unique testimony to the religion and civilization of ancient Greece. At the legendary site where Apollo slew the serpent Python, celestial cults replaced chthonian cults and introduced the old heritage of myths originating from primitive times. The Delphic oracle, over which four sacred wars were fought, is one of the focal points of Greek political history, while the Theatre and the Stadium, where the Pythian Games took place every four years, were places of community celebrations reflecting triumphant Hellenism. According to the ancients, the Temple of Apollo was where the Omphalos was located, that is, the navel of the universe, the centre of the earth. Delphi is consequently directly and tangibly associated with a belief of manifest universal significance. =

Excavated between 1895 and 1897, the amphitheater of Delphi sits up the hill from the Temple of Apollo. A huge space, able to seat an audience of up to 5,000 people, it hosted musical, poetic, and theatrical dramatic performances.

Pythia (The Oracle of Delphi) and the Priests That Worked with Here

Jean-Pierre Isbouts wrote in National Geographic History: On the appointed day, Pythia, usually a young woman and Delphi native, would drink and bathe in the waters of the Kassotis Fountain. She then entered the temple to take her place in the inner sanctum, the adyton. The oracle herself never “spoke.” Instead, she entered into a trance, brought on, according to the Greek historian Plutarch, by mysterious “vapors,” writhing and convulsing as she uttered strange sounds and cries. The priests interpreted these utterances and produced a response, which gave them tremendous power — especially if the question pertained to important political matters. [Source: Jean-Pierre Isbouts, National Geographic History, July 19, 2022]

The Pythia was chosen from a pool of young virgins. Their vow of chastity was tested after one petitioner, a military officer named Echecrates of Thessaly, fell in love and eloped with a Pythia. Delphic laws were strict: Marriage to a serving Pythian virgin was out of the question. The outraged Delphians then passed a law that “in the future a young virgin should no long prophesy” and that instead “an elderly woman of fifty” should declare the oracles.

James Romm wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The Delphic priests themselves were among history's savviest salesmen. They happily took cash in exchange for favorable prophecies. Lacking an army, they spread legends suggesting that the gods would bring disaster on any who raided their shrine. The tactic worked — until it didn't. Much of Delphi's treasure ended up coined to hire soldiers, after a neighboring city-state seized the site in the 4th century B.C. . [Source: James Romm, Los Angeles Times, February 26, 2012. Romm is a professor of classics at Bard College and author of "Ghost on the Throne: The Death of Alexander the Great and the War for Crown and Empire."]

Ritual at the Oracle of Delphi

The ritual with the oracle of Delphi took place once a month. The oracle was bathed and purified at the nearby Casralia spring and was dressed in a long, elaborately-decorated robe and a laurel crown. The seers usually took written questions and gave yes or no answers. Two surviving lead tablets with the question remain. One is by Heracleidas who asked if his wife would give him children. The other by Cleotas asked if sheep raising was a good business to get into.

The ritual with the oracle of Delphi took place once a month. The oracle was bathed and purified at the nearby Casralia spring and was dressed in a long, elaborately-decorated robe and a laurel crown. The seers usually took written questions and gave yes or no answers. Two surviving lead tablets with the question remain. One is by Heracleidas who asked if his wife would give him children. The other by Cleotas asked if sheep raising was a good business to get into.

María Teresa Magadán wrote in National Geographic History: Many ancient sources claim that people could only pose questions to the Pythia, the priestess, on the seventh day of each month, excluding the three winter months, when the god Apollo was believed to be away. After cleansing herself and burning an homage to the god, the Pythia would go to the inner sanctum of the temple, the adytum. She would sit on a tripod, and Apollo would speak through her. Priests would stand near her and interpret her answers from the god. [Source: María Teresa Magadán, National Geographic History, March 12, 2019]

The ceremony began when the oracle, known as the Priestess of Apollo and the title Pythia, touched the egg-shaped “ omphalos” ("sacred stone") which was considered the center of the world. After touching the stone she swallowed some laurel leaves and inhaled vapors from a chasm which caused her to go into a state of ecstacy.

While in this state she uttered incoherent words that a priest composed the into verses. These verses in turn were deciphered by interpreters, revealing the fortune. Whoever wished to consult the oracle had to offer a bull, a goat or a wild boar as a sacrifice. In the 5th century the oracle and the sacred stone were considered so valuable kingdoms fought wars over them.

Vapors at the Oracle of Delphi

Oracle of Delphi Treasury The vapors that drove the oracle into a state of ecstacy were believed to be produced by the eternal decomposing of the flesh of Python. The first oracles were shepherd that lived in the area and inhaled the vapors and entered ecstatic states only to die afterwards. Later it was the decided that only special priestesses would be allowed to inhale the vapors.

The source of the vapors and what they were has been a point of research and contention among historians. Plutarch described a spring that emitted “fragrance and breeze” into the Oracle’s temple, prompting the trances. Thorough searches in 19th and 20th century were unable to locate any springs like that in the Delphi area.

Research by John Hale, an archaeology graduate student at Cambridge, and Jelle de Boer, a Wesleyan University geologist mapped the area and found that two major faults intersected beneath the Oracle’s grounds and theorized that limestone deposits below the grounds released gases — specifically methane, ethane and ethylene — into the air. Ethylene in particular caught their interest because it has a sweet smell and can “induce a trance” in low doses, producing an “anesthetic state twice as fast as nitrous oxide.” Analysis of the spring water did find the presence of ethylene in the water, supporting the claim. Further research by Italian scientists led them to conclude that methane-induced oxygen deprivation was the trigger of the trances.

Oracle Inscriptions

priestess of Delphi by Collier Oracular Inscriptions:

1. Shall I receive the allowance?

2. Shall I remain where I am going?

3. Am I to be sold?

4. Am I to obtain benefit from my friend?

5. Has it been granted me to make a contract with another person?

6. Am I to be reconciled with my children?

7. Am I to get a furlough?

8. Shall I get the money?

9. Is my lover who is away from home alive?

- Am I to profit by the transaction?

11. Is my property to be put up at auction?

12. Shall I find a means of selling?

13. Am I able to carry off what I have in mind?

14. Am I to become a beggar?

15. Shall I become a fugitive?

16. Shall I be appointed as an ambassador?

17. Am I to become a senator?

18. Is my flight to be stopped?

19. Am I to be divorced from my wife?

20.Have I been poisoned?

Delphic Festival and Pythian Games

The games performed at Delphi in honor of Pythian Apollo bore the name of the Great Pythia, to distinguish them from the Lesser Pythia, held every year at Delphi, and also from the festival of the same name celebrated in other places. This festival, which at first was held every eight years, had been changed to a quadrennial one after the beginning of the 6th century B.C.; it lasted several days, and gradually many additions were made to the original contests. At first the musical competition, which comprised kithara and flute playing, was the only one; in later times, too, it was the principal part of the festival, but after the example of the Olympian games, gymnastic and equestrian contests were also added. A general truce was connected with the Pythian games as well as with the Olympian, and this lasted long enough to enable spectators from the distant colonies on the shores of the Mediterranean to journey in safety to Delphi and back. The chief events of the festival and the order of proceedings were something of this sort. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

A great sacrifice to the three gods, Apollo, Artemis, and Leto, called Trittyes probably formed the introduction. Then followed an important part of the festival, calculated to arouse lively interest in the public, the Pythian Nomos, the subject of which was the celebrated fight with the dragon Pytho by Apollo. Many suggestions have been made about the nature of this performance. One is that the fight was presented in dumb show; another that it was a song, accompanied by instruments; and, again, another very popular theory is that this Pythian Nomos was a concerto of flute solos, by means of which various stages of the fight with the dragon were represented in tone painting. Probably the most important situations — the fight, thanksgiving, and hymn of victory — could be thus represented, and, indeed, they must have attained considerable proficiency in tone painting, since even the gnashing of the dragon’s teeth was musically represented. With a view to strengthening these effects, the flute, which always remained the chief instrument, was afterwards reinforced at certain places by trumpets and shepherds’ pipes. This Pythian Nomos constituted part of the musical contest, which was of greater importance in the Pythian games than the gymnastic competition, since Apollo was essentially the representative of the musical arts. Besides the solo flute playing, the musical competition included songs with kithara accompaniment, and at first also with the flute, but this last was discontinued, being regarded as too sad and gloomy; and, instead, kithara playing without song was introduced in the musical contest. It was only in much later times, when troops of artists were called in to make the festival more splendid, with the consent of the officials of the land, that dramas were also presented at the Pythian games.

We know but little of the athletic contests which gradually found a place in the Pythian games. In essentials they were the same as those at Olympia, but the double course and the long course for boys were also added, while at Olympia these two contests were only open to men. The order of events, too, was different; the competitors were classed according to age, and each class, after completing its own contests, was able to rest while the others went through the same exercise, so that these intervals for rest enabled the boys to perform greater feats of running than they could at Olympia, where they had to enter for all their contests before the men’s turn came at all. To the usual gymnastic sports were afterwards added the race in full panoply and the pancration for boys. Equestrian competitions were early introduced; racing with full-grown horses, with four-horse chariots, and afterwards with two-horse chariots; when colts were introduced at Olympia the example was also followed at Delphi: probably the events followed in such a way that the musical contest was connected with the acts of worship, and was followed by the gymnastic, and this by the equestrian contests. The gymnastic sports were held, at the time of Pindar, in the neighbourhood of the ruined city Cirrha, south of the mouth of the Pleistos; afterwards the Delphic Stadion was to the north-west of the city, while the driving and riding races took place in the old Stadion near the ruined city of Cirrha. In later times there was also a theatre for the performance of the musical contests.

Here, as at Olympia, punctual attendance was required of the competitors; those who entered unlawfully were expelled by the servants of the Amphictyons, who were entrusted with disciplinary power. It was they who had the superintendence of the games, as well as the right of judging. Originally both these privileges had belonged to the inhabitants of Delphi; but after the reorganisation of the games in the year 586, the duties of superintendents and judges passed to the Amphictyons, or to officials appointed by them. It seems that we must distinguish between the Amphictyonic superintendents (ἐπιμεληταί), in whose hands were the arrangement of the programme, and all matters of expense, the appointment or ratification of the festive officials, etc. (ἀγωνοθεσία), and the real umpires (βραβ ς), who had themselves to make the most important arrangements for the contests, such as assigning the places for the chariots in the races and giving decisions about the victory; but we cannot attain any certainty in this matter.

Sometimes, towards the end of the age of Greek freedom, the right of superintendence was conferred on princes — as, for instance on Philip of Macedon — and in the time of the Empire it was not unusual for a rich man to bear the expenses of the ceremony wholly or in great part; though even here the old custom was, at any rate externally, observed. The prizes of victory were originally valuable gifts, tripods, etc.; at the rearrangement of the games the custom originated of giving, instead, a wreath, as was done at Olympia, made of laurel sacred to Apollo. They also followed the example of Olympia in introducing lectures and recitations by historians and poets; thus Gorgias the Sophist, delivered an oration on one of these occasions. A very important part of the festival was the great procession (πομπή), in which strangers who came to the games, embassies with their dedicatory offerings, the officials and priests, took part; and besides the offerings, which were often very splendid, valuable treasures, usually kept in the treasuries, were exhibited; costly weapons and armour, splendid garments and jewels, vases, etc., were exposed to view, so that this procession, which probably marched from the suburb Pylaea, upwards to the temple of Apollo, must have presented a very varied and richly-colored picture. As well as the triple sacrifice already mentioned, there were other solemn sacrifices, among them a hecatomb to Apollo; this was, of course, connected with the great banquet, at which there was no lack of musical entertainment.

Delphic Hymn to Apollo

This hymn to Apollo, god both of the Delphic Oracle and of music, was found inscribed on a stone at Delphi. The text is marked with a form of music notation which makes it one of the earliest pieces of music to have survived in the western world. We have no way of determining exactly how the piece would have been performed, but recordings have been made which may convey something of the sound of the work. One version is available on the album “Music of Ancient Greece,” Orata ORANGM 2013 (track 3), and another on “Musique de la Grèce Antique” Harmonia Mundi (France) HMA 1901015 (track 24). Here is a translation of the first part of the Paean.

Oh, come now, Muses, (1)

and go to the craggy sacred place

upon the far-seen, twin-peaked Parnassus, (2)

celebrated and dear to us, Pierian maidens. (3)

Repose on the snow-clad mountain top;

celebrate the Pythian Lord (4)

with the goldensword, Phoebus,

whom Leto bore unassisted (5)

on the Delian rock (6) surrounded by silvery olives,

the luxuriant plant

which the Goddess Pallas (7)

long ago brought forth.

[Source: translated by Richard Hooker]

Notes: (1) The muses were the goddesses of the arts, the word “music” comes from their name. (2) Mount Parnassus was the site of the temple of the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi, the most sacred spot in Greece. (3) The muses were also associated with a place called Pieria near Mount Olympus; but another explanation of the reference is that they were said to be the nine daughters of one Pierus. (4) Apollo. His priestess was called the Pythia, after a legendary snake that Apollo had killed in laying claim to the shrine. (5) There are many different accounts of how Apollo’s mother wandered the earth looking for a safe place in which to bear her child. (6) The island of Delos. (7) Athena. Note how the Athenian poet, even while praising the chief god of Delphi manages to bring in by a loose association the chief goddess of Athens.

Oracle of Delphi Temple of Apollo

Archaeology at Delphi

María Teresa Magadán wrote in National Geographic History: Delphi lay relatively intouched Greece became independent from the Ottomans in 1832. Greece felt a new need to encourage an appreciation of its glorious past and protection of its rich culture. It enacted laws against the sale of antiquities, created the Greek Archaeological Society, and encouraged archaeological endeavors from interested European countries. [Source: María Teresa Magadán, National Geographic History, March 12, 2019]

The excavation of Delphi would prove a gargantuan task. The homes in Kastri would need to be forcibly purchased, the residents compensated, and then relocated. Greece could not afford such a major expenditure, so it had to rely on foreign capital. In 1840 and again in 1860 archaeologists conducted preliminary studies in open areas of ground. They unearthed part of the temple substructure and a section of its supporting wall, covered with inscriptions.

Despite the difficulties of the location — wind, rain, and rockfalls — the French efforts soon yielded wonderful results. In 1893 they uncovered the main altar of Apollo’s temple, the Altar of the Chians, as well as the Sybil rock where the Pythia made her prophecies. The Athenian Treasury, also discovered in 1893, featured a truly noteworthy find: stone blocks inscribed with the words and notated music of the Hymn to Apollo.

Dating to different eras of occupations of the site, statues of athletes were common among the artifacts at Delphi. Discovered a year apart from each other, the twin statues of Kleobis and Biton date to about 580 B.C. These two massive freestanding figures stand more than eight feet tall and represent two mythological brothers famous for their strength.

In 1896 the most famous athletic statue was unearthed: the impressive bronze figure of the Charioteer. Standing about six feet tall, the freestanding statue is believed to be part of a much larger group of sculptures, now lost. It was recovered from the Temple of Apollo, where it had been buried by a rockslide in the fourth century B.C. Inscriptions near the base indicate that it was erected in the 470s B.C. to commemorate a racing victory in the Pythian Games.

The archaeologists worked hard to uncover different structures at the site. Between 1896 and 1897 the theater and stadium that held the Pythian Games were excavated, followed by the gymnasium and the Castalian Spring, and, beginning in 1898, the lower terrace or Marmaria where the Temple of Athena Pronaia stood.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024