Home | Category: Culture and Sports

OLYMPICS IN ANCIENT GREECE

stadion The ancient Olympic games were held every four years for over 1150 years — from 776 B.C. to A.D. 393. They lasted for five days — three days of major competition, and a day each for an opening and closing ceremony. Running and field events were held the first day. Horse and chariot races were on the second day and the wrestling and boxing events were held on the forth day. The number of contestants varied from year to year in each event and it was not unusual to have over 40 racers flying around the narrow track in the chariot races.

There were usually about 300 athletes competing in 15 to 18 events. Athletic and running competitions were held in the stadium and horse and chariot races were held in the hippodrome. Since athletic contests began as part of a religious ceremony no admission was charged. Money for the construction of buildings and temples was supplied by donations from rich patrons and from booty claimed in wars with neighboring city states. Women were not allowed to attend men's competitions and any woman caught at the games ran the risk of being thrown off a cliff. [Source: Lionel Casson, Smithsonian, February 1990]

Every free-born Greek was allowed to take part in the ancient Greek Olympics. Non-Greeks were strictly rejected, at any rate during classical and Hellenistic times. It was not till the time of the Roman Empire, when its glory had long departed, that this practice was abandoned. They also excluded all who had committed murder or any other great crime, or forfeited the rights of citizenship, and before the beginning of the contest a strict examination was held into the claims of all who desired to take part. At first only youths and men were admitted; from 632 B.C. onwards boys were allowed to contend, at any rate in some of the sports. We hear of women taking part or being victors in the Olympic games, but this does not mean that they appeared in person; in the chariot races and riding it was not the custom for the owner of a horse to drive or ride, and thus rich women who were interested in the training of horses could let them run at the Olympic games; and since it was not the charioteer or rider, but the trainer and owner of the horses who was crowned, they might thus obtain the prize. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

RELATED ARTICLES:

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES: TRAINING, NUDITY, WINNERS AND CHEATERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WRESTLING AND BOXING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

Judges at the Ancient Olympics

The judges at the ancient Olympics were appointed by the Elians, on whose territory the games took place. Their number varied in the course of years. At first, in 576 B.C., two citizens were chosen by lot to arrange and superintend the contests; but a hundred years later there were nine judges appointed, three for the equestrian contests, three for the pentathlon, and three for the rest of the sports; to these nine a tenth was soon added, then for a short time the number was reduced to eight, and afterwards once more increased to ten, which remained the appointed number.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

They were chosen by lot even in later times. As their decisions were of extreme importance, it was regarded as no small matter to undertake this responsible office; in fact, the judges had to be trained in a special building in the market-place of Elis, in the arcades of which they spent the greater part of the day for ten months, to be instructed in their duties by the guardians of the laws (νομοθύλακες), and in particular to acquire an accurate knowledge of gymnastic rules. When the time of the games arrived, they took a solemn oath in the court-house at Olympia, before the altar of Zeus Herkeios; their period of office extended only over a single festival.

Their duties were to make the arrangements for the contests, and all the festivals connected therewith; to examine the competitors as to their right to enter; to superintend the training of the athletes and their teachers in the gymnasium; to see that the athletes really entered for the contests which they had chosen, and that everything was done according to established custom, and the laws of the games were in no way broken; for this purpose they also had disciplinary power, and a right to impose considerable fines, and even sometimes inflict corporal punishment.

Finally, in case of uncertainty, they had to give judgment about the victory, if necessary, by a majority of votes. A combatant who was not satisfied could appeal against their decision to the council of Olympia, but he could not afterwards be pronounced victor; the most he could obtain, should it appear that the judges were in the wrong, was their condemnation to pay a fine. Under the judges were officials who helped to maintain order and carry out their ordinances; and all the attendants present — and this must have been a considerable number, owing to the great concourse of spectators and combatants — were under their orders.

Religion and Politics at the Ancient Olympics

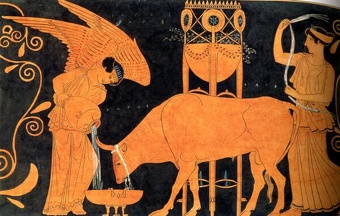

The Olympic games began with the sacrifices of a pig to honor Zeus and a black ram to honor Pelops. During the games a three-month truce was declared and all the athletes attending the games were guaranteed safe passage. At the games themselves spectators and contestants were required to leave their weapons outside the stadium before they entered.◂

Stephen Instone wrote for the BBC: “Religion pervaded the ancient Olympics. Zeus was thought to look down on the competitors, favouring some and denying victory to others. 'You could spur on a man with natural talent to strive towards great glory with the help of the gods', says Pindar in a victory-ode. If an athlete was fined for cheating or bribery (human nature stays much the same over a few millennia), the money exacted was used to make a cult statue of Zeus. [Source: Stephen Instone, BBC, February 17, 2011|::|]

“A grand sacrifice of 100 oxen was made to Zeus during the Games, and Zeus the apomuios, or 'averter of flies', was invoked to keep the sacrificial meat fly-free. Olympia was home to one of Greece's great oracles, an oracle to Zeus, with an altar to him consisting of the bonfire-heap created by burnt sacrificial offerings. As the offerings were burnt, they were examined by a priest, who pronounced an oracle - an enigmatic and often ambiguous prediction of the future - according to his interpretation of what he saw. Athletes consulted the oracle to learn what their chances in the Games were. |::|

“The Greeks tried to keep some aspects of politics out of the Olympics, but their efforts met then, as such efforts do now, with limited success. The Olympic truce was meant to lead to a cessation of hostilities throughout Greece, to allow competitors to travel and participate safely, but it was not always observed. “The great historian of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides, tells how in 420 B.C. the Spartans violated the truce by attacking a fort and dispatching hoplites, and they were therefore banned from the Games. But Lichas, a prominent Spartan, thought of a way round the ban - he entered the chariot race as a Boeotian. When his true nationality was discovered, however, he was given a public flogging at Olympia. |::|

“A victorious athlete brought great honour to his home city. The sixth-century Athenian statesman Solon promoted athletics by rewarding Athenian victors at the Games financially - an Olympic victor would receive 500 drachmae (for comparison, a sheep was worth one drachma). Thucydides represents the maverick Athenian leader Alcibiades as trying to drum up political support in 415 B.C. by boasting of his earlier successes in the Olympic Games. |::|

“And it is clear from the victory odes of Pindar and Bacchylides that the Sicilian tyrants in the fifth century aimed to strengthen their grip on affairs by competing in the equestrian events at the Games, and by commissioning famous poets to compose and publicly perform odes celebrating their victories.”|::|

Ancient Greek Olympic Spectacle

The ancient Olympics were more than just a sporting competition: they were a sporting spectacle combined with Carnival-like partying and religious rituals, with some events such as the pentathlon performed to accompaniment of flutes. In addition to more traditional athletic contests there ere also beauty pageants, eating competitions, poetry-reading contests, side shows with magicians and sword swallowers, numerologists, processions, rites, dozens of altars, public banquet halls, snacks such as roasted sow womb and feasts where 100 oxen were slaughtered. The writer Tom Perrottet described them as “the Woodstock of antiquity.”

In the Opening Ceremonies the athletes walked in one by one — naked except for perfumed oils. Each athlete was introduced by name and the name of his father and home city-state by a sacred herald. And this took place a stone’s throw from the 40-foot-high statue of Zeus, one of the Seven Winders of the World. There was no torch ceremony (that was added to the modern games at Hitler’s 1936 Olympics in Berlin).

Drunks stumbled around after drinking parties called “symposia” . Young boys in make up performed erotic dances. Prostitutes often made as much in the five days of the Olympics as the would make the rest of the year. Vendors selling love potions made with horse sweat and chopped lizard did equally well. A great deal of flirting appears to have gone on even without females in attendance at the events. A messages inscribed in the stadium at Nemea reads: “Look up Mischos in Philippi — he’s cute.”

The opportunity of appearing before so great a number of their countrymen, and thus attaining sudden fame, was a very attractive one for poets and writers, who in those days were little assisted by the bookselling trade. The custom of holding lectures or reciting poems before the assembled people originated in the 5th century B.C., when it is said to have been introduced by Herodotus, who read aloud a portion of his history at Olympia, though this story is not entirely removed from doubt. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

It is, however, a fact that from that time onwards recitations of this kind became commoner; thus Gorgias the Sophist, and Hippias the Elian, held long discourses here; and similarly, Prodicus and Anaximenes, Lysias, Isocrates, etc., lectured at Olympia; and in later times this was a frequent occurrence. Occasionally, though less often, works of art were here exposed to view; thus, a painter, Aetion, exhibited his picture of the marriage of Alexander the Great and Roxana, and the astronomer, Oinopides, of Chios, exhibited a brass tablet which was to explain a new method of calculating the time, discovered by him. This last, however, turned out a failure. The publicity of the Olympic festival was also used in other ways. Important decrees relating to solemn pledges, treaties among states, mutual acknowledgment of meritorious actions, decisions to confer crowns, or other matters of importance, which it was desirable to bring into universal notice as soon as possible, were proclaimed by the solemn voice of the herald and then graven in bronze or stone, and set up in the Altis.

Dates and Preparation for the Ancient Olympics

The dates were meticulously planned. Astronomical calculations ensured that the third day of the Games coincided with the second moon following the summer harvest. This meant the Games were typically held between August and September. If the same calculations were used in 2024, the Olympics would have begun August 17 and ended on August 21. Heralds travelled to all major Greek cities around the Mediterranean to announce the dates of the Games, along with the sacred truce. Hostilities were banned during the period around the Games to ensure safe passage for those travelling to and from Olympia. [Source Adolfo Arranz and Han Huang, Reuters, August 1, 2024]

Once the herald departed, the city began a frantic search among its young male athletes, with the aim of selecting the most outstanding to represent them in Olympia. For several months, athletes would dedicate themselves to their training with an increased passion and discipline, fueled by the hope of being chosen to represent their city. During this period, criminal trials were suspended, and the execution of capital punishment was prohibited. During the herald’s stay, sumptuous banquets were held.

After a period of time, judges revealed the names of the athletes selected to represent the city in the upcoming Games. About two months before the start of the Games, and depending on the distance that separates their city from Olympia, a delegation including athletes and trainers headed towards Elis. This city hosted of the Games, and was not far from the venue of Olympia.

According to Olympic rules, athletes were required to stay in Elis for approximately six weeks before the start of the Games. During this time, they underwent rigorous training under the guidance of their personal trainers, as well as trainers designated by the Olympic council. These “official” trainers ensured that the selected athletes were worthy representatives. Three days prior to the Olympics, athletes, along with authorities, musicians, and coaches, marched from Elis to Olympia. Then, following two days of intense preparation, the five-day festival can commence.

Opening Ceremonies and Drawing of Lots at the Ancient Olympics

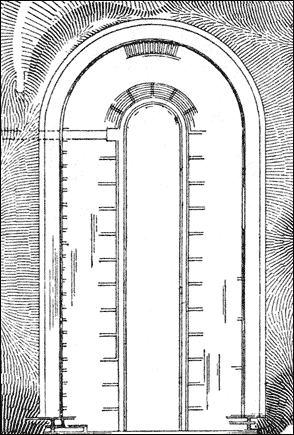

Olympia stadium entrance We can form some general idea of the succession of events and the arrangement of festivities during the five days of the festival, although we are not fully acquainted with all the details. A preliminary ceremony was the entrance of the embassies from the various Hellenic states. All the states considered it a matter of importance to send their representatives equipped with as much splendour as possible, and therefore the richest people were always chosen for the purpose. Since a great deal of splendour was shown by these delegates at the festive processions with their chariots and horses, their magnificent utensils, etc., they probably held a grand entry on their arrival, and thus the spectators, at the very beginning of the festival, were able to gratify their love of fine sights. No doubt the whole proceeding began with a sacrifice to Zeus, in whose honour the games were held, and who was regarded as their director.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Next, the umpires, the athletes who entered for the contests, and the trainers who had come with them, took a solemn oath in the court-house at Olympia. After a swine had been sacrificed, the competitors had to swear that they possessed the full rights of citizens, that they had fulfilled all the conditions which were necessary for admission, and were ready to submit to the regulations. In spite of this oath, an examination into their claims took place; it was not only necessary to prove the right of citizenship, but also the appointed training for the contests by the athletic diet already described, and on this account the presence of the trainers was desirable, if not indispensable, at the examination and oath. The horses for the races were also examined. It is uncertain whether the lots to determine the groups of competitors were drawn on this first day.

The drawing was preceded by a prayer to Zeus Moiragetes, the Director of Destiny; then the charioteers drew lots for their places at starting, and the others for their order of entry. The runners were divided into groups, probably of four; the lot decided the order in which they were to follow one another; and the victors in these races had then to run once more for the prize. This however was probably only the case with the single and double course, since it is not likely that there were so many competitors for the more difficult long course and the race in full panoply.

Wrestlers, boxers, and pancratiasts drew lots from an urn, in which small lots, of which a pair was marked with the same letters, were thrown; each competitor drew out one. Those who drew the same letters had to fight together; the victors then fought afresh. If there were more than two victors, they probably drew lots again in the same way. At last there was only one pair left, of which one was victor in the whole contest. It sometimes happened that when these lots were drawn the number of combatants was unequal, and thus one was left without an opponent. He was called the third combatant, and it was a very lucky thing to draw this lot. Of course, it would be a very unusual piece of luck for one person to be third combatant at all the drawings, and thus be able at last to meet, with his strength unbroken, an opponent who would have sustained many contests already; still, to draw this lot even once was to have a distinct advantage. There was, of course, a certain amount of unfairness connected with it, but they seem to have found no other way out of the dilemma; still, in most cases, when the victors and the third combatant drew afresh, it might be left to chance to see that one person was not too highly favored. Sometimes a competitor was lucky enough to obtain a wreath without any contest at all; for instance, if only two had entered for a particular contest, and one of them did not appear in time or abandoned the fight. Many celebrated athletes could obtain a prize thus by the mere terror of their names. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Olympic Experience in Ancient Greece

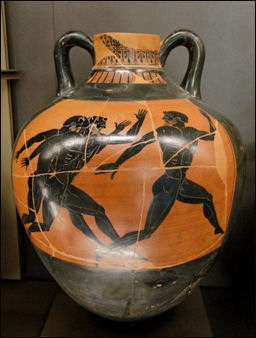

Panathenaic amphora Kleophrades Around 40,000 spectators showed up for the Olympics. Admission was free. Spectators spent much of their time on their feet. There were no seats. If one sat down on the embankments that served as stands it was difficult to see. The Greek word “ stadion” literally means “a place to stand.”

At the ancient Olympics there were no hotels. restaurants or public transport — Olympia was essentially empty except for a few caretakers and priests when the Olympics was not going on. There was only one inn and that was reserved for ambassadors and dignitaries. The rich spectators slept in elaborate tents while most everyone else slept underneath the stars or improvised shacks. Many speculate Olympia at the time of the Olympics resembled a shanty town. Nigel Spivey described being there as “persistence inconvenience and unpleasantness in human experience — overcrowded, underequipped, made bearable only by the quality of the spectacle.” Even Aristotle slept with snoring strangers in a shack.

Vendors sold wine, cheese, olives, wine and bread and the water supply system, which consisted of a few wells and cisterns was often over taxed. In mid summer the rivers were often dry. Much of the water was brought in by mule. Sanitation was a big problem. No one bathed. The smell of sweat must have hung heavy in the air. Supplying water and sanitation for such a large crowds was such a problem that people sometimes ied of dehydration and fever. It wasn't until the second century A.D., nearly 900 years after the Olympics had been going on that an aqueduct and a proper waste system was built by Herodes Atticus of Athens, the richest man in Greece at that time.

Cooking fires created a cloud of smoke. Crowds were kept in line by whip-wielding local officials. Biting flies were a big problem and many offerings were left of the altar of Zeus to keep them away. “But of course,” the Athenian philosopher and sports enthusiast Epictetus wrote, “you put up with it tall because it’s an unforgettable spectacle.”

Olympia was located in a remote area and getting there no easy task. Many made the entire 340 kilometers journey from Athens by foot. Many died in ship wrecks sailing from places as far away as Spain and the Black Sea. But for Greeks the Olympics were almost the equivalent to Mecca and every able body citizen was expect to attend at least once in their lifetime.

Olympic Spectators

Among the ancient Greeks, a pilgrimage to Olympia to see the athletic events and to participate in the sacrifices to Zeus and other festivities was something of great importance and many people attended several times. “Those headed off to the Olympics were making a religious pilgrimage and anyone who interfered with their passage was deemed to have committed a sacrilege against Zeus himself- something no Greek would do lightly. Wars were suspended, personal feuds were put on hold, and bandits and mercenaries took a holiday so that the travelers could make their way to and from the Olympic site without fear for their safety. Depending on the distance and the weather, it could be a daunting trip. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

Every free man might be present at the contests and other festivities, provided his means permitted him to defray the expenses of the journey and of a stay in the festive city. Naturally the greater number of the spectators came from the neighbouring states of the Peloponnesus; but, still, many came very long distances. So great was the interest roused by these contests that people from all classes came to view them; and even men of the highest intellectual eminence took pleasure in them. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Despite the difficulties a remarkable number of Greeks, including statesmen and generals, such as Themistocles, Cimon, Philopoemen; philosophers, such as Thales, Chiron, Pythagoras, Plato; orators, such as Gorgias, Lysias, Demosthenes; poets, such as Pindar, Simonides. Socrates made the trip more than once. Socrates offered the following advice to a timid prospective spectator: “What are you afraid of? Don't you walk around all day in Athens? Don't you walk home to have lunch? And again for dinner? And again to sleep? Don't you see that if you string together all the walking that you do in five or six days anyway you can easily cover the distance from Athens to Olympia?

Thucydides wrote in “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” (c. 404 B.C.): “It was at this time, after the purification, that the Athenians first celebrated the quinquennial festival of the Delian games. There had been, however, even in very early times, a great assembly of the Ionians and the neighboring islanders held at Delos; for they used to come to the feast with their wives and children, as the Ionians now do to the Ephesian festivals, and gymnastic and musical contests were held, and the different cities took up bands of dancers. [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 47-53]

The interest in the Olympics was revealed by the endurance with which the spectators continued to watch the games, in spite of the fact that they took place in the very hottest season, and lasted for the greater part of the day; from early morning, when they went to the Stadion in order to secure a good place, till late in the afternoon, when the decision was given, they watched and endured the heat, dust, crowding, and thirst, either standing or squatting, according as space permitted, with that patience and endurance of which only the people of the south are capable. No doubt there were noisy expressions of sympathy during the contests, encouraging or mocking cries, applause and sounds of sorrow, since all feelings are expressed in a violent manner by southern nations. Women were not allowed to be present at the games. The statement that the maidens of Elis were an exception to this rule is scarcely credible. Those women or girls who had come to the festival to accompany competing husbands, sons, or brothers, had to remain on the other side of the Alpheus. In consequence of the great number of spectators, inns and lodging-houses were built to accommodate those who had not, like the sacred envoys, brought their own tents with them. Moreover, as already indicated, a kind of fair was connected with the Olympian festivities; traders, with all manner of wares, some of them objects directly connected with the festival, such as fillets, flowers, food, etc., and other useful articles, set up their booths and tents; and, thus, along with the festival, there was a busy commercial activity, such as was common in every place where great crowds of people met together at fixed times.

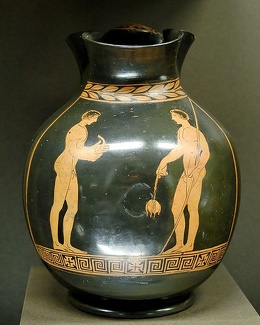

his drinking cup (500-475 BC) depicts the fight between two boxers and two pankratiasts; The pankratiasts try to gouge out each other's eyes; The umpire is about to punish them for this

Honoring the Champions at Ancient Olympics

On the last day of the ancient Olympics the prizes were distributed. The prize, as is well known, was the simplest possible — a mere wreath of olive, which a boy, both whose parents must be alive, according to the old tradition, cut with a golden knife from a wild olive tree in the Grove of Altis. Another outward token of victory was the palm branch granted to the victor, and, in consequence, the palm as a token of victory often appears in the statues of the Olympic conquerors. In olden times the wreaths to be distributed were placed on a brazen tripod; but Kolotes, a pupil of Pheidias, constructed a magnificent table of gold and ivory for the purpose, which was usually kept in the temple of Hera. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

It was the duty of one of the judges to crown the head of the victor with the wreath after it had been previously surrounded by a woollen fillet. During this solemn act the herald announced the name of the victor, as well as of his father and his native city. The importance attributed by the ancients to the victory in the Olympic games was such that this proud moment, when the victor received his reward amid the applause of the whole people, and, as it were, before the eyes of all Greece, was a sufficient compensation for all the troubles and difficulties involved in the preparation for the contest. Still, there were many other honors which fell to his lot, both in Olympia and at home in his own country.

After the name of the victor had been announced, sacrifices and banquets took place. It is not certain whether the great sacrifice of the Elians, a hecatomb offered to Zeus as the supreme director of the contests, took place at the conclusion of the festival, or at the beginning; in any case, numerous sacrifices of thanksgiving were offered by the victors and also by the delegates sent from other states. Very often the victor’s sacrifice was combined with that of his countrymen; for the state to which the conqueror belonged considered itself honored by his victory, and it was the duty of the delegates to exhibit as much splendour as possible at the sacrifice as well as at the procession connected with it. These solemn processions, which made the last day of the feast a specially magnificent one, were accompanied by flutes and kitharas, and, perhaps, also by the singing of choruses. They probably marched at first round the altars, while the flames of the sacrifices were burning on them, and afterwards touched at all the sacred places near the holy Altis.

In the afternoon a great banquet, given by the Elians to the victors, united them all in the town hall; but even this was not the end of the festivities, for feasting continued in the evening and far into the night at entertainments given by the victors to their relations and friends, who had hurried to the spot. These were more or less magnificent according to the means of the givers, though sometimes the state to which they belonged bore a part of the expenses. These festive gatherings were also honored by music and song, and it was on these occasions that the songs of victory (ἐπινίκια), specially composed in praise of the victor and his family, were often sung, along with old songs, supposing it to have been possible in this short interval to write, compose, and study one of these hymns of victory. Most of the odes, especially those of Pindar, which have come down to us, were not performed on these occasions, but at the festivities held in honor of the victor in his own country, which were often celebrated there from year to year.

Pindar’s Olympian Odes

Pindar hailing Olympic champions

Pindar: Olympian Odes (c. 470 B.C.); No. 9: “Fit speech may I find for my journey in the Muses' car; and let me therewith have daring and powers of ample scope. To back the prowess of a friend I came, when Lampromachos won his Isthmian crown, when on the same day both he and his brother overcame. And afterwards at the gates of Corinth two triumphs again befell Epharmostos and more in the valleys of Nemea. At Argos he triumphed over men, as over boys at Athens. And I might tell how at Marathon he stole from among the beardless and confronted the full-grown for the prize of silver vessels, how without a fall he threw his men with swift and coming shock, and how loud the shouting pealed when round the ring he ran, in the beauty of his youth and fair form and fresh from fairest deeds.” [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 47-53]

No. 10: “Ample is the glory stored for Olympian winners; thereof my shepherd tongue is fain to keep some part in fold. But only by the help of Zeus is wisdom kept ever blooming in the soul. Son of Archestratos, Agesidamos, know certainly that for your boxing I will lay a glory of sweet strains upon your crown of golden olive and will have in remembrance the race of the Locrians in the west.”

No. 11: “Who then won to their lot the new-appointed crown by hands or feet or chariot, setting before them the prize of glory in the games, and winning it by their act? In the foot-race down the straight course of the stadion was Likymnios' son Oionos first, from Nodea had he led his host: in the wrestling was Tegea glorified by Echemos: Doryklos won the prize of boxing, a dweller in the city of Tiryns, and with the four-horse chariot, Samos of Mantinea, Halirrhotios' son: with the javelin Phrastor hit the mark: in distance Enikeus beyond all others hurled the stone with a circling sweep, and all the warrior company thundered a great applause. Then on the evening the lovely shining of the fair-faced moon beamed forth, and all the precinct sounded with songs of festal glee, after the manner which is to this day for triumph.”

No. 13: “Also two parsley-wreaths shadowed his head before the people at the games of Isthmus, nor does Nemea tell a different tale. And of his father Thessalos' lightning feet is recorded by the streams of Alpheos, and at Pytho he has renown for the single and for the double stadion gained both in a single day, and in the same month at rocky Pan-Athenaios a day of swiftness crowned his hair for three illustrious deeds, and the Hellotia seven times, and at the games of Poseidon between seas longer hymns followed his father Ptoiodoros with Terpsias and Eritimos. And how often you were first at Delphi or in the Pastures of the Lion, though with full many do I match your crowd of honors, yet can I no more surely tell than the tale of pebbles on the sea-shore.”

Death and the Dark Side of the Olympics

Daniel Mendelsohn wrote in the New York Times magazine: “Everything about the ancient Olympics was darker, rougher, more brutal than its modern counterpart... Ancient Games had their origins as somber celebrations of death. The earliest reference in Western literature to funeral games is Homer's description, in the 23rd book of the ''Iliad,'' of the games that Achilles ordered to commemorate the death of his companion, Patroclus; all four of the great Greek athletic competitions that constituted what was called the ''circuit'' — the Olympian, Pythian, Nemean and Isthmian Games, some held every four years, some every two — had their cultic origins either in commemorations of the deaths of mythic mortals or monsters. One anthropological explanation for the close association of ancient Games with funerals is a primitive practice according to which, when someone was killed, a fight to the death would be held between the suspected killer and another man; with the irrefutable logic of superstition, the loser was then judged to have been the guilty party. [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, New York Times magazine, August 8, 2004 ]

“Death was, indeed, by no means a stranger at the Greek Games, particularly in the ''heavy'' events like boxing or pankration, a kind of all-out boxing cum wrestling that was considered the acme of combat sports. But what strikes us now is not even how often athletes died, but how willing to die they were. During a pankration match in the Olympics of 564 B.C., as a competitor lurched around the ring half-dead, his trainer suggested that ''full dead'' was the hero's option: ''What a noble epitaph,'' he is said to have shouted, ''not to have conceded at Olympia!''” Also, “There's a funerary inscription at Olympia that reports, of an Alexandrian fighter nicknamed the Camel, that ''he died here, boxing in the stadium, having prayed to Zeus for victory or death.''

“This seems extreme but is entirely in keeping with the Greek ethos. Part of the reason the ancient Games were so uncompromising and often violent has to do with what was at stake. The Greeks, for the most part, had no heaven; with some notable exceptions, good and bad all went to the same gray, characterless, drizzly underworld after death, and that was that. In the absence of a post-mortem reward for moral goodness, the one thing you could strive for was immortal fame — doing something so glorious that men would talk of you in years, centuries, millenniums to come. As anyone who suffered through ''Troy'' knows, this was the all-powerful motivation for the heroes of Homer's ''Iliad,'' but it was also often the motivation for ordinary, real-life inhabitants of the Greek city-states, for whom there was no conceivable earthly achievement higher than an Olympic victory. (Athenian families, at the birth of a baby boy, would place an olive wreath on the front door, signaling their hope that the infant might one day be a victor at the Olympics.)

“And so, whereas today's Olympic committee prefers to ''celebrate humanity'' (an official slogan of contemporary Olympiads), the Greek athlete wanted only to be celebrated himself; it was his one ticket to immortality.” To come in second was perceived as defeat. Pindar described losing athletes returning home in shame: They "shrink down alleyways, bitten by failure."

“It is difficult for us today to conceive of the extent to which a ferocious competitiveness fueled so much of Greek culture, virtually no aspect of which was not somehow organized into a competition; for the inhabitants of a city-state like Athens, civic life was an endless stream of athletic contests, poetry contests, drama contests, beauty contests. For the Greeks, whatever was worth doing was worth competing for — and winning at. It's no accident that three out of the four Games on the ancient circuit were established early in the sixth century B.C. — precisely the historical moment that a new kind of warfare, which required an extraordinary degree of cooperation among infantrymen, was beginning to predominate in Greece, replacing old-style battle with its displays of individual heroism. It's as if, lacking a military outlet for their competitive energies, the Greeks inevitably poured them into these new athletic events. But the desperate rawness of the battlefield — and its stark, all-or-nothing logic — was never very far beneath the surface.

“Victory or death. This, in the end, is the grimly pure ethos of the contest, where there is (however much we like to pretend otherwise) only one winner; you wonder whether this is why the poet Pindar referred to Olympia as the ''mistress of truth.'' Death was the origin of the ancient athletic contests, and the all-or-nothing logic of death hovered over the ancient Games, where there were no illusions about what victory meant, or could often cost. But the kinds of truth about which the pagan Greeks — who lived in intimate, unsentimental and regular contact with death, violence and warfare — had no illusions are precisely those that we like to play down or bury under sentimental and infantilizing trappings: adorable bears, cutesy eagles, rag-doll gods and goddesses. Every four years we all like to indulge in the sentimental fantasy that we're communing with the pure and noble spirit of the classical Greek past. But purity comes at a price, and that price is the truth: what is victory, and what is defeat? “

Critics and Supporters of the Ancient Olympic

Stephen Instone wrote for the BBC: “Not all Greeks admired athletes. 'It isn't right to judge strength as better than good wisdom', Xenophanes wrote sixth to fifth century B.C.. Just because someone has won an Olympic victory, he says, they won't improve the city. The tragedian Euripides expressed similar sentiments in his play Autolycus, now only surviving in fragments. In it he describes how athletes are slaves to their stomachs, but they can't look after themselves, and although they glisten like statues when in their prime, become like tattered old carpets in old age. Galen, physician and polymath of the first century AD, also attacked athletics as unnatural and excessive. He thought that athletes eat too much, sleep too much and put their bodies through too much. [Source: Stephen Instone, BBC, February 17, 2011|::|]

Xenophon wrote in “Hellenica (c. 370 B.C.): “If one should win a victory thanks to the swiftness of his feet or when competing in the pentathlon there in the sanctuary of Zeus by the streams of Pisa at Olympia, or if one should gain the prize in wrestling or painful boxing, or in that fearful contest people call all-in-fighting, to his fellow citizens he would be thought more glorious to look on than ever, and he would gain from his polis the right to meals at public expense and a gift which would be his personal treasure. And if his victory were won with horses, he would also gain all these things, even though he is not as worthy as I. For our wisdom is better than the strength of men or horses. For even if there were a good boxer among the citizens or one skilled in the pentathlon or wrestling, or, indeed, even if there were a great sprinter, which holds the front rank among the athletic achievements of men, the polis would still not be better governed because of this. A polis would gain little joy if someone should win in competition by the banks of the Pisa, for that victory would not fill its storehouses. [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 47-53]

Instone wrote for the BBC: “But in the end the detractors of athletics lost out to the sympathisers. The person who most idealised the Olympics was Pindar, from Thebes, midway between Delphi and Athens. Pindar composed odes for victors at the Olympic and other Games in the fifth century B.C. comparing their achievements to those of the great heroes of the past - such as Heracles or Achilles - thus raising them to an almost divine level. He thought that, though mortals, their superhuman feats of strength had temporarily elevated them to another realm and given them a taste of incomparable bliss. 'For the rest of his life the victor enjoys a honey-sweet calm' he writes. |::|

“For Pindar, the Olympics stood out among the Games “'Water is best; gold like fire that is burning during the night is conspicuous outshining great wealth; but if, my heart, you desire song to celebrate the Games, look no further than the sun for another radiant star hotter in the empty day-time sky, nor let us proclaim a contest better than Olympia.'

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024