Home | Category: Culture and Sports

ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES

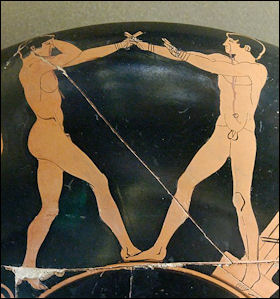

runners at the Panathenaic games in 530 BC The Greeks saw competition as a way to earn respect and honor. They considered an athlete to be, in the words of the Historian Pindar, one "who delights in the toil and cost," and the Greek word for athlete, in fact, was the same as the one for "miserable" and "wretched." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “ During competition and training, athletes were usually naked and covered with olive oil to keep off the dust. They trained in the gymnasium or xystos (covered colonnade), often coached by past victors. The Greeks believed that their love for athletics, among other things, distinguished them from non-Greeks, and only Greek citizens were allowed to compete in the games.”[Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

Thucydides wrote in “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” (c. 404 B.C.): “The Lacedaemonians (Spartans) were the first who in their athletic exercises stripped naked and rubbed themselves over with oil. But this was not the ancient custom; athletes formerly, even when they were contending at Olympia, wore loin-cloths, a practice which lasted until quite lately, and still prevails among Barbarians, especially those of Asia, where the combatants at boxing and wrestling matches wear loin-cloths. [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 47-53]

Greek athletes were not all that different from their modern counterparts. They both had secrets to success. In 668 B.C., a Spartan athlete attributed his victory in the 200-meter dash to a diet of dried figs. There was also pressure and high expectations. One athlete called an Olympic victory "the wreath or death." They also said similar things. When asked what will be right way to live, the wrestler and philosopher Plato said, "A man should spend his whole life at 'play.'" Professional athletes, who took good care of themselves, were able to continue their contests for a good many years, sometimes thirty or more, and were thus able to pile honor on honor and reward on reward.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FAMOUS ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK OLYMPICS: WHAT THEY WERE LIKE, ATMOSPHERE, PURPOSE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WRESTLING AND BOXING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

Requirements and Rules for Ancient Olympic Athletes

Athletes were required to be freeborn males of Greek descent. Contrary to myth, Olympic athletes were not amateurs. They were often well paid and backed by sponsors, patrons or head's of state and spent all of their time training. Top athletes were given money, tax exemptions and draft deferment. They traveled around with entourages and were paid appearance money as well as prize money. Although they competed for their home city states it was not uncommon for some to switch allegiance for money. The same held true for sought after coaches.

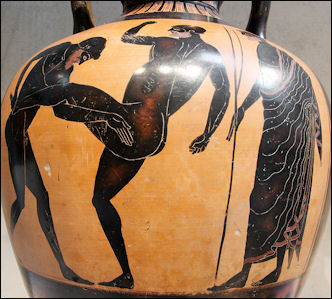

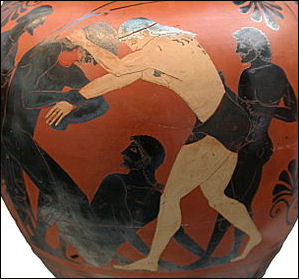

Boxing scene For the athletes it wasn't just a matter of showing up on the day of the competition and performing. 30 days before the games began; athletes had to register in person before the ten Olympic judges. Many would be accompanied by their personal trainers and coaches. The first thing that the judges did was to ensure that the athlete presenting himself was truly Greek and eligible to compete. The second thing was to make certain that those who wanted to compete were capable of doing so at the highest level. To that end, the judges conducted trials and workouts calculated to weed out those at the weaker end of the spectrum. The competitors ate together at a common mess to ensure that no one gained an advantage with secret recipes and magic potions. It is interesting to note that there were no team sports at those Olympics. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “Near Coroebus is buried Orsippus who won the footrace at Olympia by running naked when all his competitors wore girdles according to ancient custom. They say also that Orsippus when general afterwards annexed some of the neighboring territory. My own opinion is that at Olympia he intentionally let the girdle slip off him, realizing that a naked man can run more easily than one girt. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Ancient Olympics, Women and Nudity

Olympians competed sometimes or partly in the nude. In some competitions and during the opening and closing ceremonies they often covered themselves in perfumed oils. Even jockeys sometimes wore nothing. Wrestlers in the nude often had their foreskin tied over the tip of the penis for protection. The main exception to the semi-nudity rule was the charioteers who wore long white robes. Nudity was seen as a way of making all competitors equal by stripping social ranks they could otherwise express with their clothes.

The athletes competed in front of an almost all male audience. There is some confusion as to whether women could attend events. There are accounts of women being threatened with being tossed from a cliff if they were discovered in the stands although the punishment it seems was never carried out but the same source also described a special seat for a woman priest. Most scholars believe married women were barred although unmarried women and girls were allowed in the stands.

In the first few Olympics the athletes competed with their clothes on and no one is exactly sure why they decided get rid of them. Some historians say the precedent was set in a race in 720 B.C. in which Orsippus of Megara lost his shorts in the middle of the race and won anyway. Other historians recall a runner who was leading a race but tripped and fell and lost when his shorts slipped down.μ

Stephen Instone wrote for the BBC: “'Sow naked, plough naked, harvest naked', the poet Hesiod (a contemporary of Homer) advises. Stephen Instone wrote for the BBC: He might have added 'compete in the Games naked', for that is usually understood to be the standard practice among the ancient Greeks. Some dispute this, for although the visual evidence for it - the painted decorations on vases - generally shows athletes performing naked, all sorts of other people (eg soldiers departing for war, which they would presumably have done clothed) are also shown unclad. Also, some vases do show runners and boxers wearing loin-cloths, and Thucydides says that athletes stopped wearing such garments only shortly before his time. Another argument is that it must have been impractical to compete naked. On balance, however, it is generally thought probable that male athletes were naked when competing at the Games. [Source: Stephen Instone, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Ancient Olympic Foreskin Coverings

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast As is quite well-known, ancient athletes competed in the buff. But this is only partially true: while exposing one’s penis was acceptable you were expected to cover the head of your penis with what, to ancient Greeks, was the most attractive part: the foreskin. As a result, circumcised men were not permitted to enter events. Some aspiring competitors sported unconvincing prosthetic foreskins or underwent risky medical procedures to try and manufacture new ones. As a piece of clothing, the foreskin could be styled. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 25, 2021]

Beginning around 500 B.C., uncut Olympians, began to wear their prepuce using a kynodesme (quite literally a “dog leash”). The device worked by tying a piece of leather around the foreskin and securing the penis around the waist or tucking it under the penis itself. The point, as you can imagine, was to streamline the athlete’s body and prevent things flying around. It also had the side benefit of helping to elongate the foreskin. Think of it as the ancient equivalent of swimmers shaving their body hair. The only other accessory was body oil, which was likely to have been applied for aesthetic purposes as it helped Olympians appear more godlike.

Following the belief that ejaculation weakened men and sapped their physical reserves, some ancient athletes wore a kuno (a kind of genital piercing) in order to prevent them becoming aroused. Despite many studies disproving it, the myth that sexual activity saps athletic performance persists. Muhammad Ali apparently abstained for six weeks before a fight. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 25, 2021]

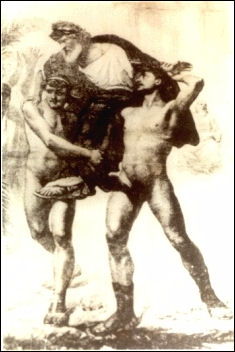

Gymnasiums — Ancient Olympic Training Centers

Pankration The “ gymnasium “ (derived from the Greek word for “place to exercise naked”) was where the athletes worked out. It was usually nothing more than an open area adjacent to the sacred grove. Athletes arrived with bags with oil flasks and strigils used for scraping their body clean after exercising. There were special training facilities for athletes. One of the most famous in the Italian colonies was Krotons. The athletes from this city were so adept that during one Olympics the top seven finishers in one footrace were Krotoniates. "Not only did Kroton have the best athletes, it had the most beautiful women," one historian told National Geographic, "The great painter Zeuxis came here to find models for a painting of Helen of Troy."

A typical Greek gymnasium was an open court surrounded by columns with areas for running, jumping and throwing and a covered area for wrestling and bathing. Young men often spent a greater part of their day in the gymnasium, occupying themselves as much with chatting and hanging out as working out. It is no surprise that Sophists conducted their first meetings in gymnasiums and Plato set up his Academy and Aristotle set up his Lyceum next to gymnasiums.

Athletes used oil to protect their skin form injuries, reduce sweating and make wrestlers slippery to their opponents. Some have suggested it was also done to make their bodies more aesthetically pleasing for the audience. The strigil was a strange-looking device usually made of bronze. It was used mostly by athletes to scrape dirt and oils off their bodies after competitions and training. The athletes did this rather than wash with soap. The strigil looked sort of like a long spoon with the spoon part stretched and elongated and bent forward and the handle stretched and bent backwards. Strigils first appeared in Greek art in the 6th century B.C. and became symbols of athletes, some of whom where found to have them buried with them in ancient graves. One vases shows an athlete presenting his strigil to a dog to lick.

Ancient Olympic Training

There are a large number of vases, especially those of the late sixth and early fifth centuries, ornamented with scenes from the wrestling-schools and gymnasia. The place is indicated by the objects hung on the walls, such as jumping-weights, a diskos, or an oil-flask and a strigil for removing sand and oil. The trainer is usually present, represented as a mature man, wearing a himation and carrying a forked rod. The flute-player in a long, spotted robe often accompanies the exercises or plays for the jumper. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

As part of their training, athletes in the ancient Olympics ate honey for energy and meat for strength. Boxers used primitive punching bags and head-gear for training. Massage was an important element of training. One reason the athletes performed and trained in the nude is because it was easier to massage oils into their body, which was regarded as a key to victory. On the subject of training too hard Galen wrote: “perhaps someone will say that they have a blessing in the pleasure of their bodies. But how can [that be] for during their careers athletes are in constant pain and suffering not only because of their exercise but also because of their forced feedings? And when they reach the age of retirement, their bodies are essentially...crippled.”

Trainer There was a difference between the athletic training of youths, continued into manhood with a view to strengthening the body, and the professional exercises of the athletes; we must, therefore, say a few words about the position as well as the training of the latter. As the public games increased in importance, and the glory gained by the victors induced ambitious youths and men to strive for a wreath in the athletic contests, and thus gain undying fame for themselves and their native city, it gradually became the custom for especially strong and skillful athletes to make the development of their body for these athletic contests the object of their life, in order, by constant practice, by a particular diet and mode of life calculated to increase their strength, to attain the highest position in this profession, and thus to be almost sure of victory. In this way “agonistics,” which was originally only a development of exercises in accordance with the rules of art, became a regular profession, and those who devoted themselves to it were distinctively known as athletes. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

As athleticism became a profession and a means of making money, it ceased, of course, to be an occupation worthy of a free and noble citizen; and it is, therefore, natural that at Sparta, where every profession by which money could be made was looked down upon, it should have made no way, and that in other places, too, it was only men of the lower classes who devoted themselves to it, however enticing it might seem to an ambitious youth who desired to attain the material advantages enjoyed by the victors in these contests, as well as the glorious honors with which they were specially distinguished.

The athletes received their training from a trainer, who must be carefully distinguished from the gymnastic teacher of the boys. The trainer instructed his pupils in the higher branches of exercises, practised frequently with them, and probably also accompanied them to the public games, in order to instruct them to the very last moment, since the victory of a pupil was also honorable and advantageous to the master. The exercises probably took place in the gymnasia belonging to the trainers, or in the public gymnastic places; and consisted not merely in a methodical increase in the usual athletic exercises until the highest achievements were attained, but also in many which were not practised elsewhere, and which were not calculated to harden the body or make the limbs supple.

Diet of Ancient Olympic Athletes

Along with the athletic training they observed, as already mentioned, a very careful mode of life, which was superintended by the rubber, whose half-medical training has been already alluded to. This diet was in part observed at all times, but was especially severe just before the games, at which an athlete had to appear. In ancient times the principal nourishment of the athletes was fresh cheese, dried figs, and wheaten porridge; in later times they abandoned this vegetarian diet for meat, and gave the preference to beef, pork, and kid. Bread might not be eaten with meat, but was taken at breakfast, while the principal meal consisted of meat; confectionery was forbidden; wine might only be taken in moderate quantities. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

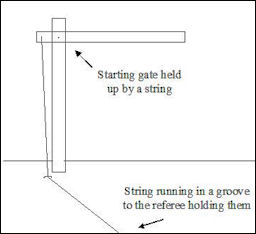

hysplex In addition to this diet, which was prescribed to the athletes for the whole year, a special training had to be followed at times, especially when preparing for the games, which lasted for more than three-quarters of the year; at these times the athletes every day, after the conclusion of their practice, had to consume an enormous quantity of such food as was permitted them, and then digest it in a long-continued sleep. By gradually increasing the amount, an athlete succeeded at last in consuming an enormous quantity of meat, and at length this became a habit and even a necessity.

By this means they attained, not, it is true, hardening of the muscles, but the corpulence which is often represented in the ancient pictures, and which might be advantageous in certain contests, especially in wrestling and the pancration, since it enabled them more easily to press down and wear out their opponents; on the other hand, this artificially-produced corpulence was very unhealthy, and it is natural that these athletes were liable to many kinds of disease, especially apoplectic strokes. The training and mode of life of the athletes just described was obviously not suitable for all kinds of athletic contests. Such diet would have been very pernicious for running and jumping.

Ancient Olympic Rules and Cheaters

The Olympic events were presided over by judges who wore indigo robes and flower garlands. Everyone had to submit to the local laws of Olympia when they entered the competition. A great deal of effort was made to ensure that competitors fought on equal footing regardless of their wealth, social standing or popularity. Before the competitions, athletes were required to take an oath on a slice of boar’s meat that they had not used any magic to boost their performance. There were stories about Olympic athletes who took psychedelic mushrooms of a competitive edge.

The “ hysplex “ was a complicated devise designed to prevent false starts. Runners that made false starts were beaten by the official whip bearers. Cheaters were fined and the money was used to build "Zanes," statues that bore the name and offense of the cheater so he would go down in infamy for his humiliation. Some of the statues were built with money taken in from fines taken from athletes caught taking bribes.

The ancient Olympics were not immune from corruption and scandal. In the Olympics in 396 B.C., sporting judges were punished for making dishonest decisions. Later the boxer Eupulos was caught paying a rival to throw a bout. Philip of Macedonia, Alexander the Great's father, payed Olympic organization large sums of money to allow Macedonians, regarded as Barbarians, to participate. He also bought off rivals in chariot races. The legendary Prince of Pelops fixed the race against his main rival by hiring someone to sabotage his chariot axle by substituting a wax fittings for a metal one, causing the chariot to break apart in mid race, killings it driver, a rival king. Pelops in turn won the hand of a beautiful woman who became his wife.

In 66 A.D. the Roman Emperor Nero arrived at the Olympics with a retinue of 5000. He entered several events, and with his bodyguards standing ominously close, he won them all. During the chariot race he fell off his mount and all the other contestants stopped until he got back on. He later went on to win the race even though he did not finish.◂

Ancient Olympic Winners and the Glory Accorded Them

Diagoras of Rhodes The winners at the Olympics were awarded an olive wreath cut from a sacred tree. It was the equivalent of a gold medal. In the Nemean Games they received a crown of fresh celery. In the Delphi Games the crown was made of bay leaves. At the Isthmia Games it was made from dry celery There was no second or third prize, nor were records important. The only thing that mattered was winning. The exception was the Panathenaea at Athens There, prizes were given to the winner and the top five runners up. Some of the prizes could be quite lavish. On scholar estimated the winner of the boy’s foot race won an amphorae filed with 1,944 liters of olive oil. The amphora themselves were decorated with images of the event won and were like trophies.

It was the obligation of the victor's city state to give the victor a grant usually around five times the average wage of a working man. Winners were also given free meals, the best seats at festivals and exemptions from taxes. Statues were erected in their honor. All around Olympia were statues of athletes among the statues of gods and goddesses. Some winners were given a pension for life. By some estimates an Olympic victory could be worth half a million dollars in today's money. Some Olympic winners were extolled with odes, given slaves and oxen and provided with free food for life. A common prize was 100 olive-oil filled amphorae (olive oil was very valuable in ancient times). When the winner returned home he was garlanded again with wreath of olive leaves and a statue was raised in his honor. Sometimes a hole was punctured in the city's fortification with the understanding being that the victor was so strong he would deter any incursions.

The wrestling and boxing and the pancration were the most popular sports, and it was in these that the more celebrated athletes of antiquity, whose names have come down to us — such as Milo, Polydamas, Glaucus, and the rest — were specially distinguished. The victors in the Olympian games were allowed to set up a statue in the Grove of Altis, at Olympia, at their own expense or that of their relations, sometimes even of the state to which the victor belonged; and at home, too, they very frequently had the same honor of a public statue assigned to them.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

When they returned from the games, they held a solemn entry into their own town, dressed in purple, riding on a car drawn by four white horses, accompanied by their friends and relations and a rejoicing crowd; it was even an ancient custom to pull down a piece of the city wall, in order to show that a city which could produce such citizens required no walls for its defence. Then followed a banquet in honor of the victor, in which hymns were sung in his praise. Rewards were also given in coin. At Athens, after the time of Solon, the victor in the Olympian games received 500 drachmae, the victor in one of the three other great national contests a hundred drachmae; in later times they even had the right of dining every day at the public expense in the town-hall , and they also enjoyed the honor of sitting on the front benches of the theater.

Ancient Greek Poems for Olympic Winners

Peleus An ode for the winner of boy’s footrace in 460 B.C. went:

Now for the Alkimedon: blessed with victory

at Olympia, by the slopes of Kronose.

On first sight he was splendid; sure

he proved his beauty in the test.

Triumphant form each bout.

He puts his homeland on the heralds’ lips’

“Aegina of the long oars!”“

By contrast losers sometimes came home in humiliation. A lament for one unsuccessful athlete went: “the loser’s hateful return, the jeering voices, the furtive back alleys.”

On winning itself Pindar of Thebes wrote in the late 5th century B.C.:

In athletic games the victor wins the glory his heart desires

as crown after crown is placed on his head.

when he wins with his hands or swift feet.

There is a divine presence of a judgment of human strength.

Only two things, along with prosperity, advance life’s sweetest prize:

if a man has success and then gets a good name” .

Don’t expect to become Zeus. You have everything

if a share of these two blessings comes your way” .

Dim View Taken of Ancient Olympic Athletes

Not everyone admired ancient Olympians and professional athletes. The unlimited admiration which the mass of the people, and especially the youth, who were easily won by exhibitions of strength, gave to famous athletes, stands in strong contrast to the judgment pronounced on them by men of real intellectual development, especially by the philosophers. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

They rightly complained that this one-sided development of the body was perfectly useless to the State, since the athletes were only capable in their own domain, but were quite unable to endure fatigues and undertake military service; they pointed out that the mode of life which aimed merely at increasing the bodily strength tended to dwarf the intellect, and that, therefore, the athletes were absolutely useless for political as well as for all intellectual purposes. Wise educators, therefore, disapproved of athletic training, and, indeed, the greatest warriors and statesmen of Greece seem always to have despised it.

Euripides wrote "Of all the countless evils throughout Hellas none is worse than the race of athletes...In youth they strut about in splendor, the idols of the city, but when bitter old age come upon them they are cast aside like worn out cloaks." Galen, one of the founders of medicine, added "they spend their lives in over-exercising, in over-eating, and over sleeping like pigs. Hence they seldom live to old age and if they do they are crippled and liable to all sorts of diseases.”μ

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Most of the information about Greco-Roman science, geography, medicine, time, sculpture and drama was taken from "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. Most of the information about Greek everyday life was taken from a book entitled "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum [||].

Last updated September 2024