Home | Category: Culture and Sports

FAMOUS ANCIENT GREEK ATHLETES

Theogenes was a popular athlete. One night one of his enemies was killed while trying to flog his statue, which fell on him. The statue was tried and found guilty of murder and dumped in the sea. The next year Thasos experienced an unprecedented famine. When the Thasos elders consulted the Oracle of Delphi they were told to bring back the political exiles. When this didn't work it was suggested that maybe the exiles referred to was the statue of Theogenes. The statue was then dredged up, replaced and chained down so it wouldn't fall over again. The famine soon ended and people returned to worship the statue for another five hundred years. According to the Guinness Book of Records, Leonidas of Rhodes won a record 12 running titles in the ancient Olympic games between 164-152 B.C.

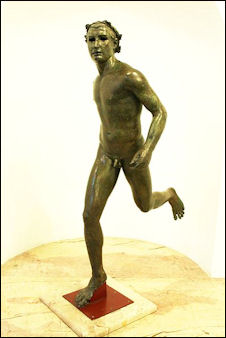

Stephen Instone wrote for the BBC: Milo of Croton, in southern Italy, would come high on anyone's list of greats. He was Olympic champion in the men's wrestling six times in the sixth century, besides winning once in the Olympic boy's wrestling, and gaining seven victories in the Pythian Games. He is said to have carried his own statue, or even a bull, into the Olympic arena, and to have performed party tricks such as holding a pomegranate without squashing it and getting people to prize open his hand - nobody could. [Source: Stephen Instone, BBC, February 17, 2011|::|]

“Then there is Leonidas of Rhodes, who in the second century B.C. won all three running events at four consecutive Olympics. Another great Rhodian athlete was Diagoras, who in the fifth century B.C. won at all four of the major Games (Olympic, Pythian, Nemean and Isthmian). His three sons and two of his grandsons were also Olympic champions. |::|

“Superhuman heavyweights were regarded with special awe. Cleomedes, a fifth-century Olympic boxing champion, killed an opponent at the Olympics, was disqualified, went mad and smashed up a school. Not a recipe for special reverence, you might think. But the Greeks regularly explained abnormal feats and states of mind by saying that something divine, or a god, had entered whoever was affected in this way, and Cleomedes ended up receiving semi-divine honours as a hero. |::|

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES: TRAINING, NUDITY, WINNERS AND CHEATERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK OLYMPICS: WHAT THEY WERE LIKE, ATMOSPHERE, PURPOSE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WRESTLING AND BOXING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

Milo, the Great Olympic Wrestling Champ

hero cult Milo, who lived around 500 B.C., was perhaps the most famous Olympic athlete during ancient times. He the Olympic wrestling champion six times. In 520 B.C. he was the only wrestler. Everyone else it seems was afraid to challenge him. In addition to his wrestling skills, he was also known for his appetite. In a typical meal it was said he ate 7 pounds of meat, 7 pounds of bread and a gallon of wine. Once he reportedly carried a full grown bull around the stadium, then ate it one day. To show off his strength he used to have chords wrapped around his head and bust them by holding his breath and expanding the veins of his temples. But despite his awesome powers he died after being eaten alive by a pack of wolves when he got his hand stuck in a tree.◂

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece” (c. A.D. 175): Milo of Croton won six victories for wrestling at Olympia, one of them among the boys; at the Pythian he won six among the men and one among the boys. He came to Olympia to wrestle for the seventh time, but did not succeed in mastering Timasitheus, a fellow-citizen who was also a young man, and who refused, moreover, to come to close quarters with him. It is further stated that Milo carried his own statue into the Altis. His feats with the pomegranate and the quoit are also remembered by tradition. He would grasp a pomegranate so firmly that nobody could wrest it from him by force, and yet he did not damage it by pressure. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“He would stand upon a greased quoit, and make fools of those who charged him and tried to push him from the quoit. He used to perform also the following exhibition feats. He would tie a cord round his forehead as though it were a ribbon or a crown. Holding his breath and filling with blood the veins on his head, he would break the cord by the strength of these veins. It is said that he would let down by his side his right arm from the shoulder to the elbow, and stretch out straight the arm below the elbow, turning the thumb upwards, while the other fingers lay in a row. In this position, then, the little finger was lowest, but nobody could bend it back by pressure.”

Pheidippidesa and the Ancient Greek Marathon

The marathon is an event run in the modern Olympics. It was not part of the ancient Olympics. It commemorates an event, though, that occurred in ancient Greece. The marathon story is based on an account of the “ Battle of Marathon in The Histories” by Heredotus. It was written about 50 years after the battle took place.

The marathon is an event run in the modern Olympics. It was not part of the ancient Olympics. It commemorates an event, though, that occurred in ancient Greece. The marathon story is based on an account of the “ Battle of Marathon in The Histories” by Heredotus. It was written about 50 years after the battle took place.

The Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C. is one the most famous battle in ancient Greece. A Persian force of 20,000 men and a fleet of 600 ships landed on the Plains of Marathons, about. 25 miles from Athens. They were defeated by the Athenian army, under the command of general Miltaides, even though it was outnumbered six to one. Miltaides organized his forces so that its strength was in the wings.

When the Athenians learned that the Persians had arrived,Pheidippides, an Athenian runner, ran 150 miles to Sparta to seek the help of Sparta. The Spartans didn't participate because they were holding a religious ceremony at the time. The Athenian army, which was camped out in the foothills on the edge of the Marathon plain, was forced to fight against the Persians without any help from the Spartans

After the Persian army was routed the panic-stricken Persians retreated to their boats. This time Pheidippides ran 26.3 miles from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory of the Greeks over the Persians and then fell dead after he gave the message: Rejoice! We conquer!"

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “When the Persians had landed in Attica Philippides was sent to carry the tidings to Lacedaemon. On his return he said that the Lacedacmonians had postponed their departure, because it was their custom not to go out to fight before the moon was full. Philippides went on to say that near Mount Parthenius he had been met by Pan, who told him that he was friendly to the Athenians and would come to Marathon to fight for them. This deity, then, has been honored for this announcement. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

Revising the Marathon Story

Marathon The story of Pheidippides, who has also been referred to by other names, is generally believed to be an amalgamation of separate incidences. The run to Athens apparently involved the army, which after winning at Marathon, hustled back to defend the city against the remnants of the Persians, who had regrouped in their ships and planned an attack that never materialized.

The Marathon to Athens run appears to be a myth. Herodotus described the 150 mile run to Sparta by Pheidippides but said nothing about running to Athens and dropping dead. After the Persians held Marathon they tried to attack Athens while it was unguarded but the Athenians returned home to repel the attack. The Pheidippides running to Marathon to Athens appears to be an embellishment of that story. If the story is true it means that Pheidippides about 325 miles in less than a week: 150 miles from Marathon to Sparta, 150 miles back to Marathon, where he likely participated in the battle, then ran to Athens. No wonder he dropped dead.

The legend of the Pheidippides provided the inspiration for French scholar Michael Breal to suggest adding a "marathon" race to the program of the 1896 Olympics to his friend Pierre de Coubertin. The distance between Marathon to Athens is about 24 miles but the distance was extended to 26 miles and 385 yards at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London so Queen Victoria could watch the race from the window of her palace.

History books have the battle and the run taking place in September, when Greece is relatively cool, but reexamination of historical and astronomical data indicated that the run more likely took place in August, when Greece is very hot. This would explain even better why Phidippides dropped dead. The original September 12th date of the run was determined in the 19th century by German scholar August Boeckh based on Herodotus’s accounts, which includes the phases of the moon. Scholars at Texas State University reexamined the data and came up with an August 12th date based on the fact Boeckh failed to take into consideration that the Spartan calendar, from which the date was determined, was one month different than Athenian calendar.

Women in the Ancient Greek Olympics

Spartan woman Nearly all the competitions in the Olympics were between males, although sometimes unmarried girls, divided into different age groups, competing in running events at a separate sporting event called the Heraea held at a different time than the Olympics at the Temple of Hera. The girls competed with "their hair hanging loose" and with a "tunic reaching to a little above the knee, with the right shoulder bare as far as the breasts."

In Sparta women competed in front of the men nude in "gymnastics," which at that times meant "exercises performed naked." The Spartan women also wrestled but there is no evidence that they ever boxed. Most events required the women to be virgins and when they got married, usually the age of 18, their athletic career was over. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Otherwise women competitors were barred from the games and not even allowed to go near the stadium. The mother of a boxer once disguising herself as her son's trainer and was revealed for what she was when her robe slipped after embracing her victorious son. The judges spared her life with the understanding she would never show up again. The boxer's mother episode, some say, is another reason why male competitors competed in the nude.

In 396 B.C. Princess Kyniska became the first woman to sponsor a winning entry in the tethrippon, a four horse chariot race, at the Olympics.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Most of the information about Greco-Roman science, geography, medicine, time, sculpture and drama was taken from "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. Most of the information about Greek everyday life was taken from a book entitled "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum [||].

Last updated September 2024