Home | Category: Culture and Sports

COMPETITION IN ANCIENT GREECE

The Greeks loved competition. Musicians and poets, as well as athletes, were pitted against one another in contests, and even dramatic plays were staged as tournaments with the winner being selected by a jury. There were also competitions for drinking, singing and male beauty. Socrates believed that arts and sports were the most important factors in man's development. There were also associations with the gods. Castor and Pollux, the twin sons of Zeus, were the gods of boxing, wrestling and equestrian sports.

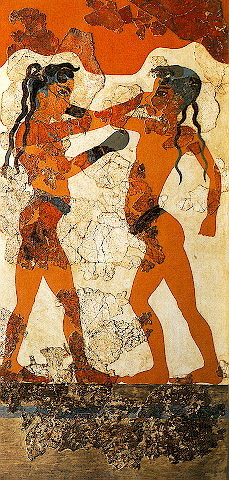

Evidence for interest in athletics dates back to the sixteenth century B.C. in Minoan Crete, where frescoes show what looks like boxing and bull-leaping. Homer describes chariot races, wrestling, weigh throwing and running events sponsored by Achilles to honor a Patroclcus. The Homeric poems contain many references to athletics, as the funeral games of Patroklos in the Twenty-third Book of the Iliad, the games among the Phaeacians in which Odysseus took part (Odyssey VII). In Homer's time sports were unorganized and no rules had as yet been devised for them. The seventh century was especially the period of organization during which the great festivals became fixed in time and in the number and kind of contests, and by 570 B.C. the four great Panhellenic festivals — the Olympian, the Pythian, the Isthmian, and the Nemean — were established. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Mesopotamians and Egyptian didn't have organized sport. While the Greeks had the Olympics, the Romans had gladiator contests. For the Greeks there was an aesthetic, even sexuality, to athletics. “Each age has its beauty,” Aristotle wrote. “In youth, it lies in the possession of a body capable of enduring all kinds of contest...while the young man is himself a pleasant delight to behold.”

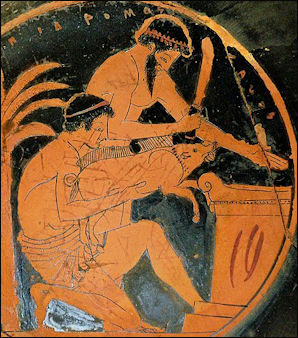

Sometimes music and poetry contests were staged in conjunction with Olympic-style athletic competitions. Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “There was anciently a contest held at Delphi, of players on the cithara, who executed a paean in honor of the god. It was instituted by the Delphians. But after the Crisaean war the amphictyons, in the time of Eurylochus, established contests for horses and gymnastic sports, in which the victor was crowned. These were called Pythian games, in addition to the musical contests.” [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 47-53]

RELATED ARTICLES:

WRESTLING AND BOXING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK OLYMPICS: WHAT THEY WERE LIKE, ATMOSPHERE, PURPOSE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES: TRAINING, NUDITY, WINNERS AND CHEATERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu. Exhibitions: Games of the Gods: The Greek Athlete and the Olympic Spirit at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; The Games in Ancient Athens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

Purpose of Sport in Ancient Greece

Winning was everything in ancient Greek sports. The Greeks were primarily into individual sports in which there was only one winner. Contestants did not bother to enter events in which they thought they were going to lose. Winners received a crown of wild olives branches and prestige — that was sometimes worth a lot of money. Losers did not shake the hands of the victor and they returned to their hometowns "by back ways...sore smitten by misfortune." The sportsmanship sometimes manifested in the modern Olympics is something that mainly comes from upperclass Englishmen. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Sport was seen as more than just sport. In his book “ Ancient Greek Athletics” Stephen G. Miller wrote: “Athletics was not simply about competition; it concerned winning a prize. Sport for sport’s sake was not an ancient concept...There was an acceptance at both popular and philosophical levels, of prime imaginative and imitative purpose in play, an understanding, essentially that, all games were war games.”

In addition to sport there was athletics for exercise. This was carried out at gymnasiums and the primary purpose was prepare and train and keep them in shape afterwards (every citizen under 60 could be called up for military service). Physical fitness was only viewed as something one did for himself; it was a civic duty integral to preservation of the state. At the gymnasiums, older men taught boys about their duties to the community, proper behavior and how to carry oneself as a man. Many exercises of a partly military character were also practised in the gymnasia. Besides throwing the spear, which was regarded as an entirely gymnastic exercise, and was practised at the public contests, there was archery.

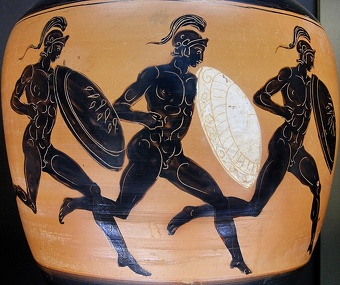

A foot-race is represented on one of the Panathenaic amphorai and the cast of a bronze statuette in Tübingen which shows a contestant in the race for hoplites (heavy-armed foot-soldiers), at the starting-line. The art of fighting in heavy armor, hoplomachy, was taught to Greek boys by a special master as part of their athletic training. A most interesting scene of this kind decorates the shoulder of a hydria of the late sixth or early fifth century where two men armed with helmet and shield are fencing with spears to the music of a flute-player. Plato alludes more than once to the attention given to this branch of physical training in his day, and the prestige enjoyed by teachers of the art. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Sacrifices were held to mark the beginning of special events and to commemorate the birthdays of the important gods and goddesses. Wine, barley and blood of the sacrificed cattle, pigs and sheep were offered on the altars of the gods and then consumed by the people attending the sacrifice to symbolize the union between mortals and gods. Sports competition were sometimes seen contests for divine favor.

Exercise in Ancient Greece

Sacrifice of a boar Exercise was an important part of ancient Greek life. In much of Greece it was the basis of the education of girls as well as boys. Even in Athens, known its emphasis on intellectual pursuits, the training of the body was an important feature of the education of boys and youths, and was also diligently cultivated even afterwards for the sake of developing and strengthening the body. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Among these exercise were dumb-bell lifting and jumping and exercise which bore resemblance to our own exercises. Exercises involving bending the knees were especially popular at Sparta, and also practised by girls there. Others included thrusting the arms forward and backward whilst standing on tiptoe, hopping on one foot, or changing the foot. Tug-of-war-style rope-pulling was also a favorite practice.

We are expressly told that these dumb-bells were also used in ancient exercises for strengthening the shoulders, arms, and fingers, and on many old vase paintings, where we see dumb-bells in the hands of youths, the attitude suggests such exercises and not jumping. In one painting one of the men holds two such dumb-bells in his hands; it is not easy to decide whether he is preparing to jump, as is usually supposed, or is only practising dumb-bell exercises. Still, the latter seems to have been a subordinate use only, and the chief use of the dumb-bell was in jumping. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

In the case of the youth represented with dumb-bells, taken from an engraved discus, it is uncertain whether he is using them merely to exercise his arms or to help him in jumping; possibly he is taking a preliminary run. Other representations of jumpers are given below, in two images. It is very probable that these spring-weights were used for the long jump, but not for the high jump, where they would be rather an impediment than an assistance.

The ancient Chinese, Greeks, Indians and Persians also practiced forms of tumbling and acrobatics to prepare for battle. The word gymnastics is derived from the Greek word for "naked" (“gymnos” ). The sport was revived in the 1700s in Germany as an activity for schoolchildren.

Jumping as a Sport in Ancient Greece

One of the chief exercises in the gymnastic schools and at the sports was jumping. Along with running, quoit-throwing, wrestling, and boxing, jumping was regarded even in the Homeric age as part of exercises, but we know very little of the mode in which it was practised. In the historic period we find the same kinds of jumping as at the present day, namely, the high jump, the long jump, and the high long jump; among these the long jump was of the first importance, and was the only one in use at the contests. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

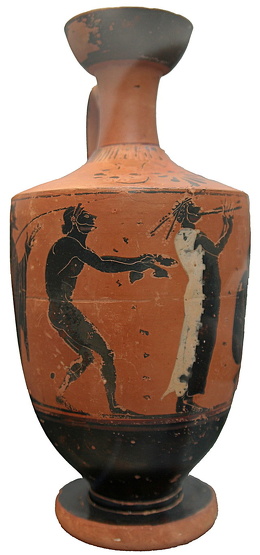

For jumping, weights called halteres were used; a black-figured lekythos is decorated with a scene of athletes practicing, two of them hold halteres. The drawing is sufficiently detailed to show the shape well. On the psykter and a vase fragment are jumpers at the take-off, and a boy preparing for a jump decorates the interior of a kylix. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

While we, however, confine ourselves more to the jump with or without a spring-board, and use no artificial means except perhaps a pole, in ancient times weights were largely in use, and though they required a greater effort on the part of the jumper on account of the additional weight, yet they gave him some advantage by increasing the impetus. These weights are simply dumb-bells made of metal or stone, and resemble in shape those which we use at the present day for very different purposes.

There were two kinds. The older form resembled the segment of a circle, somewhat smaller than a semicircle, part of the circle being used as a handle. This older kind of dumb-bell, which is represented on many vase pictures, was used in later times chiefly for hygienic purposes. Another kind came into general use for sports, and especially the Pentathlon; these exactly resembled our modern dumb-bells, for which, indeed, they served as models. A round ball is fastened at either end of a massive handle, bent into something of a curve, and sometimes — especially when they were used not merely to exercise the arms but in leaping — one of these balls was larger and heavier than the other, and this, in the leap, was thrust forward.

In running, previous to jumping, they held the dumb-bells behind them, and at the moment of jumping thrust the arms violently forward; the impulse given by the weight then communicated itself also to the legs, and enabled them to cover a longer distance. We, therefore, often find jumpers represented in pictures holding their arms stretched in front of them; and practical attempts in recent times have convinced us that the importance of the dumb-bells in jumping was due not so much to a backward motion communicated by them, as to the thrusting forward of the arms. On springing down the arms were thrust backward again, as we may also learn from the pictures, and thus a firm and safe standing posture was attained.

A difficult question is whether the ancients made use of leaping-poles. There is not a single picture of which we can say with certainty that it represents exercises with a leaping-pole, although on vase paintings of gymnastic scenes we do very frequently see sticks or poles, but it is always possible to find another interpretation for these. Thus they may be javelins, such as were used for throwing, or measuring rods, with which the superintending teachers or judges measured the length of a jump or a quoit-throw, or they may be merely sticks carried in token of official position. None of the writers afford any direct information about the use of leaping-poles; they are hardly mentioned except in references to occasional leaps over trenches with the help of a pole, and mounting horses by help of a lance; and, accordingly, we may infer that they did not play an important part in ancient exercises.

Another disputed question is whether the ancients used a spring-board. Some references among the later writers seem to suggest that they made use of a little elevation, from which they took the long jump, which was far the commonest and the only kind in use in the contests. There is nothing, however, to show that this elevation was of wood, and thus gave the jumper an advantage in consequence of its elasticity; it seems to have been only a little mound of earth. The course of events was something of this sort: all who took part in the contest took their stations in a row behind a line drawn in the sand of the wrestling school, and jumped from there in turn; of course, this was not done without previous running, for some of the achievements of the ancients in the long jump would have been quite impossible without running. Accordingly, they must have run from the appointed place to the mound and jumped from that. Where the first jumper stopped a fresh line was drawn with a pick-axe, such as we often see on vase pictures in the hand of a youth or superintendent, and they were also used to loosen the earth in order to lessen the shock in jumping down. Those that followed, of course, tried to jump even further, and every longer jump was again marked by a line, while the short ones were left unnoticed, unless, as in the case of the Pentathlon, the object was to have several victors. Finally, the result of the various jumps was determined by long measuring chains.

What the ancient writers have told us about the wonderful achievements of the Greek athletes in the long jump, sounds almost fabulous; especially the story about Chionis, who is said to have jumped 15.85 meters (52 feet), and Phayllus, who jumped 16.8 meters (55 feet) . Modern writers on exercises have declared these statements impossible and exaggerated, in spite of the fact that they rest on good authority; but it is not right to declare our disbelief simply on account of our modern gymnastic training, which is entirely different from the Greek, since the elasticity of the sinews and the muscles, which come into play in jumping, has not been nearly so well developed from earliest youth upwards as it was in Greece; moreover, these accounts refer to especial tours de force, and were only remarkable exceptions. In any case, Greeks must have demanded a great deal even from ordinary jumpers, otherwise they would not have considered the jump, which in itself is one of the easiest exercises, one of the most difficult achievements in the gymnastic contests.

Running as a Sport in Ancient Greece

Running was mentioned by Homer as among the sports practised by the youth of Phaeacia; it was very popular, too, in later on, and formed an important part of the athletic contests which took place at the great Hellenic festivals. Speed was not of as much importance as endurance, and overcoming difficulties of ground; for they did not run on firm earth, but in soft sand, where it was doubly difficult to run fast, since the feet sank in if they were too firmly set down.

The signal for running was given by the dropping of a rope stretched out in front of the runners; in running, they either held their arms with the elbows closely pressed to their sides or swung them violently and regularly backwards and forwards, corresponding in time to the feet; the former attitude was probably reserved for the long course, when it was a question of preserving an equal speed, and the latter for the quickest course, in which the swinging of the arms might be a help; even here, however, the rule held that a good runner should adopt a slower motion at first, and only gradually proceed to his greatest speed.

The pictures of runners, which are very common on vase pictures, especially on the so-called Panathenaic prize amphorae, generally show the peculiarity of holding the front leg very high up, while the other is set far backwards, and seems only to touch the ground with the toes. Now in ordinary pictures of runners we generally see the front leg resting on the ground and the other thrown out far behind, and this is sometimes found on antique pictures, but less often; we therefore must suppose that quick running in ancient times consisted rather in a series of wide jumps, in which only the toes touched the ground. In one vase painting we see four runners moving thus from left to right; their left legs are thrown far forward, their right legs back, and the arms swing with a motion corresponding to that of the legs. The hypothesis formerly current that on the vase paintings the runners from left to right are running the single, those from right to left the long course, is, however, not tenable. The two men practising, on the vase picture are jumping in exactly the same manner; behind them another man is preparing to jump with dumb-bells, near them stands a teacher or superintendent in a cloak, with a switch in his hand; on the ground lies a quoit.

In ancient times, runners usually wore some drapery round their loins, but afterwards they had no clothing at all. There was, however, a special kind of race, called “armour-race,” which was not introduced into the Olympic games till the year 520, in which the runners wore the heavy armour of Hoplites. In ancient times, they seem to have run in full armour — that is, with helmet, cuirass, greaves, sword and spear; afterwards, if we may trust the representations on the vases, the armour-race consisted in running with helmet and round shield. This kind of race, which, of course, required still greater exertion, seems to have been only in use for the single and double course, and chiefly for the latter, but not for the horse-course, or the long course.

Torch Race and Running Events in Ancient Greece

There were four kinds of racing, according to the length of the course: the single course, the double course, the horse race, and the long course. The single course was the length of the race-course, or stadium — that is, six hundred feet; the runner had to measure the course from beginning to end. In the double course the same space was passed over in both directions — that is, twice. In the horse race they ran twice backwards and forwards, consequently four stadia, which therefore was the length of the course on horseback, and hence its name. There are very different accounts about the length of the long course; seven, twelve, twenty, and even twenty-four stadia have been mentioned; the last (about three miles) seems to have been the usual length at Olympia. It is impossible to say whether these various statements are due to erroneous calculations or differing customs; still there is no reason to doubt even the longest course mentioned, since many of our modern runners can achieve far greater distances, so that a course of twenty-four stadia might very well have been required as the highest achievement of a good athlete.

Our authorities, however, do not inform us what degree of speed was usual. We know that the educational and practical value of running depended not only on the attainment of great speed over a short distance, but also on the endurance necessary for achieving a long distance; and among the exercises in the gymnasia they probably laid as much stress on an even pace in the long races as on speed. But when running was practised at the contests, the moderation in speed of course gave way to the attempt to be first in the race and in consequence we hear of cases in which the victorious runner, on reaching the winning-post, fell down dead in consequence of excessive exertion, like the runner Ladas, whose statue Myron made. Therefore, the runners, as well as others who engaged in athletic contests, were in the habit of previously rubbing their bodies with oil in order to make their limbs flexible. In running, three or five generally entered at the same time; when there were more they seem to have been divided into parties of four, and in that case the winning party had to run once more to decide the final victory. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The torch-race was more a matter of skill than of speed or bodily strength. This was especially popular at Athens, and there constituted an important part of certain festivals, especially the Panathenaea, and the festivals of Hephaestus and Prometheus, but had nothing to do with the athletic contests at the great national games. The youths who took part in the torch-race, lighted their torches at an altar in the Academy, and ran together from there, with burning torches to some appointed place in the town. In this race the victor was not he who ran fastest, but he who first arrived at the goal with a burning torch.

It was important, therefore, to run quickly, and at the same time cautiously, so that the torch might not be put out. The expenses of the arrangements, which, however, cannot have been very considerable, belonged to the so-called Liturgies, the charges voluntarily undertaken by certain wealthy citizens. They also had to superintend the practising, or, at any rate, to see to its being done. If we may judge from ancient representations of the torch-race, the runners sometimes, besides the torch, bore a shield on their left arm, and also some head-covering, and, since it was not really a question of great speed, some light article of clothing.

Discus-Throwing in Ancient Greece

Discus-throwing — throwing a heavy disc as far as possible — was mentioned in the Odyssey. The youth of Phaeacia played it, but Odysseus excels them all, and sends the disc hurled by him beyond all the marks of the other players. Discuses are also mentioned as an amusement of the suitors, and among the funeral games in honour of Patroclus. Homer mentions stone and iron discuses; in later times metal, chiefly iron or bronze, was the commonest material. They were round and flat in shape, somewhat raised on each side, with a diameter of about a foot, and were, therefore, very heavy, and not easy to grasp on account of their smoothness. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The descriptions of ancient writers and monuments give us a very clear idea of the manner in which these discs were thrown. The discus-player, first of all, took a firm stand, and while he measured the space over which he had to throw his disc, he held it in his left hand in order not to tire the right too soon; this is the position in which we see the standing “Discobolus” in the Vatican. The attitude adopted when actually throwing is best given by the Discobolus of Myron, which has come down to us in several copies, and which is thus described by Lucian: “He is stooping down to take aim, (his body) turned in the direction of the hand which holds the discus, one knee slightly bent, as though he meant to vary his posture and rise with the throw.”

Throwing the discus was one of the oldest Greek sports. The object was to throw it as far as possible. So many representations of this sport have come down to us in statues, vase paintings, coins, and gems, that it is possible to work out the successive movements of the throw. The principle seems to have been always the same, though individuals were allowed certain differences in style. A bronze statuette shows one stance; the athlete is about to swing the discus down from the left to the right hand. The position preliminary to the swing downwards to the side, the athlete now holding the discus in both hands, may be seen on a lekythos and one of the figures on a psykter is in the same position. The well-known statue by Myron, shows the position just preliminary to the throw, an instant before the discus leaves the hand. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Discus-throwing, as well as running and jumping, was taught even to boys, but undoubtedly they used smaller and lighter discs than men. The disc from Aegina, now in the Berlin Museum, one side of which was only eight inches in diameter, and about four pounds weight, but was probably never used as an actual implement of the school.

Javelin Throw in Ancient Greece

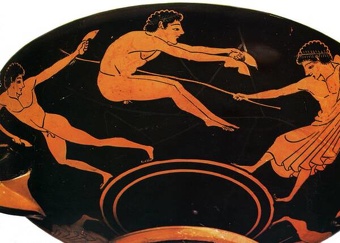

Throwing the javelin also had a practical value as preparation for warfare and was one of the commonest sports of the palaistra. In the pentathlon it was thrown for distance only, but there were competitions in throwing at a target at the Panathenaea and, no doubt, on other occasions. A thong, fastened near the center of gravity, and twisted around the hardwood shaft, acted like the rifling of a gun in insuring greater accuracy. One of the figures on the black-figured lekythos is preparing to throw a javelin, and the artist has represented the thong in such a way that the method of using it can easily be understood. The thrower holds the shaft in his hand with the first and second fingers inserted into loops in the end of the thong. As he throws, the thong unwinds, giving the missile a whirling motion. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

We find throwing the javelin mentioned in heroic times, not only as a mode of fighting, but also as a game. In the gymnastic schools of the boys and youths they often used, as we may tell from the pictures, instead of a real spear, a blunt stick of about the same length, but they must sometimes have made use of real spears with sharp points for their exercises, since the orator Antiphon tells us that one of the older boys at the gymnasium killed a younger one, who had by mistake run in the way, and this would have been impossible if a mere stick had been used. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Probably the weight of the spears was gradually increased, as also of the discuses, and the youths used heavier weapons than the boys, while the men in their turn used still heavier ones. We may, however, infer that, besides throwing a mere stick in which certainty of aim would be the object, they used actual spears, and studied especial ways of managing them, since the javelin, which was supplied with a loop or strap, had to be thrown in a quite peculiar way, while the stick had no loop, and could be quite differently thrown. This loop was near the lower end of the javelin; the thrower put the first and second fingers of his right hand through it — sometimes it was a double loop, so that each finger grasped a separate strap — he laid his thumb on the wood of the spear, which rested on the third or fourth fingers placed underneath, or else on the third finger alone; in this position the hand was drawn backwards and then aim was taken at some definite goal, the nature of which we are not acquainted with. This we learn from the Berlin disc already mentioned, and also from various vase paintings, and the figure of the giant frieze from Pergamum. The throw was either horizontal, if distance was aimed at, which was most usual, or upwards towards some raised mark.

Among the athletic exercises represented in a vase painting, throwing the spear also plays a part. We see here, on the left (near the handle), a youth represented as just about to run; on the right, near him, a second is practising dumb-bells, or else preparing to jump. Near a long-robed flute-player, whose music is accompanying the exercises, a spear-thrower is running forward, but his face is not turned forward to the mark, but backward towards the hand which holds the spear (like the throwing Discobolus), so that we must suppose that it was not a question of throwing the spear at a definite mark, but only of sending it as far as possible. Next to a bearded superintendent, wearing a cloak and holding a switch, follows a discus-player, who is about to throw the disc which he holds in the right hand. on. Other representations show us that, in throwing upwards, the handle with the loop was held downwards, but in throwing to a distance, if the object was to throw as far as possible, the right arm was drawn back and here; but if a mark was aimed at, the upper arm was kept in a horizontal position, about the height of the ear, and the aim carefully taken before throwing. The javelin used in athletic exercises and contests differs from that used in war in being constructed of very light wood, and having no lance-head like the one used in battle, but, a very thin and rather long head, obviously in order that the spear may cling more easily to the mark which was probably made of wood.

Ancient Greek Ball Sports

Ancient Greek football player The Egyptians, Greeks and Romans played ball games but ball games were dismissed as children’s games and not held in the Olympics. The Greeks played ball game called “phainmuda “ that is similar to netball. “ Episkyros “ was team game that required dodging and marking in a relatively small space. Hockey is one of the oldest stick and ball games. Early forms of hockey were played in ancient Egypt, Greece and Persia.

There were special places devoted to ball-playing just as there were afterwards in the baths or thermae. The ancient writers mention several other occupations of this kind, half-way between serious exercises and mere games. One image probably shows us one of these. It seems to represent a game with a large hard ball, which was thrown up into the air and caught on the thigh, and, perhaps, thrown up again into the air from there. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

John Fox wrote in the Los Angeles Times, Ball games and team sports “have become so integral to our very notion of sport that it would be unthinkable to host the” Olympics Games without them. “But the elevation of ball play to Olympic status is an entirely modern phenomenon. It would have been equally unthinkable in Classical times for an object as fun and frivolous as the ball to have been allowed entry to the hallowed sanctuary of Olympia. [Source: John Fox, Los Angeles Times, June 9, 2012. Fox is the author of “The Ball: Discovering the Object of the Game”.]

"It's not that the Greeks didn't love to play ball. When Odysseus was shipwrecked on the shore of Phaeacia, he encountered the beautiful princess Nausicaa playing an ancient version of dodgeball with her maids. While oxen were being sacrificed and athletes rubbed down with olive oil to compete for Zeus' honor at Olympia, ordinary Greeks were playing a silly game called ephedrismos, in which players mounted on the shoulders of teammates threw a ball at a target or to another pair of players. Scenes of women and men playing variations of this strange game of people polo appear repeatedly on painted jars and statues of the Classical period, and in much earlier scenes from ancient Egypt — suggesting it was more than just a passing fad.

"More reminiscent of today's competitive team sports was episkyros, a rugby-like game played by two teams of a dozen or so players with a feather-stuffed leather ball. The 4th century playwright Antiphanes vividly described a game in progress, handing down possibly history's first play-by-play sports commentary: "He caught the ball and laughed as he passed it to one player at the same time as he dodged another ... and all the while there were screams and shouts: Out of bounds! Too far! Past him! Over his head!"

Archery in Ancient Greece

Archery was practised at public contests in the Alexandrine age and even found a place in the curriculum of the Attic youths. This was also the case with the Cretans, who were renowned as excellent archers at the time of Plato, and probably even earlier. They used for the purpose a bow constructed of horn or hard wood; bows were of two different shapes, one which was common in the East, and was already described by Homer, in which two horn-shaped ends were connected by a straight middle piece; the other was a simpler shape, in which the whole bow consisted of one piece of elastic wood, scarcely curved at all when the bow was not bent, and which, when bent, acquired a semi-circular shape. As a rule, when the bow was not in use the string was only fastened at one end. Before shooting, it was attached to the hook at the other end by means of a little ring or eye. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

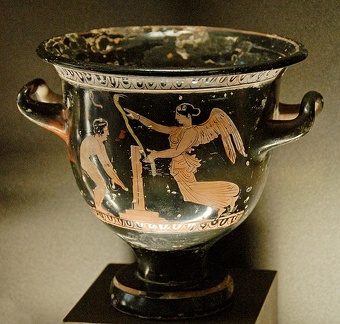

A good deal of strength was needed to bend the bow far enough to attach the string. In shooting, they drew back the feathered arrow, on which a notch fitted, along with the string towards the breast, holding the bow firmly in the left hand. One vase painting represents archery practice. The target here is the wooden figure of a cock set upon a column; of the three youths who are practising one shoots standing, the second kneeling, the common position for an archer, and the third is just about to draw his bow pressing his knee against it. All three use the second kind of bow. It is, of course, only an artistic licence that the archers are placed so near their goal; similarly the arrows are still flying while the two archers are about to shoot fresh ones.

Hunting in Ancient Greece

Those who possessed estates in the country, even when they lived in town, often went out to them to look after the management; hunting and bird-catching were also very popular occupations. The former especially was a favorite amusement. Hunting in ancient times was very different from what it is at the present day; this is partly due to the great difference between our modern firearms and the hunting implements of the ancients, partly to their almost universal custom of using nets, into which they drove the game and there killed it. These nets were used for nearly all quadrupeds which they hunted, and the strength and density of the meshes differed according to the object hunted, as well as the method of arrangement. There were in particular bag nets, which were drawn together behind the game when it ran into it, and falling nets, which were hung loosely on forked sticks, and when the animal ran against them fell down from the sticks and entangled it. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Snares were also used for catching not only hares and foxes, but also larger four-footed game, such as boars and stags. In consequence of this custom of driving the game, and bringing it to bay, bows which were calculated for longer distances were of very little use in hunting; the animals were either killed by a light javelin thrown from a small distance, or, if the game had turned to bay, with a hanger, which was especially useful in boar hunting. Dogs were used for starting the game and driving it into the nets at bay, and the ancients devoted a good deal of care to their training; indeed, the important part played by dogs in Greek hunting is expressed by the Greek name for huntsman, which means “dog leader”.

They used to hunt boars, stags, hares; beasts of prey, such as wolves and jackals, were only hunted when they were dangerous to the herds; and larger animals, such as lions and bears, did not exist at all in Greece in historic ages, although the numerous legends of lion hunts bear sufficient testimony to their existence in earlier times. Birds were caught with nets, snares, traps, and lime; and, since Greece was by no means rich in quadrupeds suitable for hunting, bird-catching was one of the most popular occupations, and also a lucrative one. On the other hand, fishing, which was carried on with both lines and nets, seems never to have become a regular sport.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024