Home | Category: Culture and Sports

OLYMPIC EVENTS IN ANCIENT GREECE

Pentathlon The core 18 Olympics events were running races, field events, wrestling and boxing and horse and chariot races. There were separate events for men and boys. There was no swimming, no marathon, no beach volleyball or for that matter no ball games or team sports of any kind.

Olympic contests included athletic and equestrian nature events but excluded drama, poetry and musical contests held at some sports festivals. The Roman Emperor Nero, supported by 5,000 soldiers, bullied competitive poetry reading onto the list of events in A.D. 67. When the Olympics were banned as a pagan ritual in A.D. 393 it consisted of 18 events. When the Olympics were restarted in 1896 it there were 43 events in nine sports. Now there are hundreds of events in about three dozen sports.

Many of the events in the ancient Greek sporting competitions were tests of skills in battle. "Since the ravines that split the Greek countryside demanded long jumps for the chase," wrote historian Daniel Boorstin, "the long jump became a regular event. But there was no high jump. The Greek athletic long jumper had to hold weights, from four to eight pounds, testing his ability to carry a weapon....The discus throw may have begun as a test of ability to throw stones in battle...In the javelin throw, as on the battlefield, to add distance and accuracy a thong was looped around a finger to give the javelin a spinning motion." The pentathlon, a test of the all-around athlete-warrior, included the broad jump, javelin, foot races, discus throw and wrestling. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

The Greeks kept no records in the modern sense. Running races were not timed (the Greeks lacked stopwatches) and measurements were not made in meters. Records were kept however for the greatest number of victories in a particular event. It was unusual an athlete to win an event more than once and even rarer for an athlete to win two different events.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK OLYMPICS: WHAT THEY WERE LIKE, ATMOSPHERE, PURPOSE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES: TRAINING, NUDITY, WINNERS AND CHEATERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WRESTLING AND BOXING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

Introduction of Different Sports to the Ancient Olympics

The introduction of different sports took place gradually. Stephen Instone wrote for the BBC: “For the first 13 Olympics there was only one event, the stadion race , which was a running race up one length of the stadium. How long this race was is a matter for conjecture, as the ancient stadium, 193 meters long, visible at Olympia now, did not exist then. In 724 B.C. a longer, there-and-back race, the diaulos, was introduced, followed four years later by the long-distance race, the dolichos, a race of perhaps 12 laps. The emphasis on running in the early years of the Olympics may reflect the perceived basic requirements for a fit soldier. [Source: Stephen Instone, BBC, February 17, 2011]

In the year 708 B.C., the pentathlon was added, and thus the most important sports — jumping, throwing the spear and discus, and wrestling — were introduced, along with running, and henceforward were regarded as one of the most attractive parts of the whole contest. In 688 B.C. a boxing-match was added. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Wrestling, and the pancration (the 'all-power' race, combining all types of physical attack) soon followed, along with and horse-and-chariot racing. A race while wearing armour was introduced in 520 B.C. and even a mule race (in 500 B.C. but it was not generally popular). So the changing shape of the modern Olympic programme is not without precedent, though the ancient Greeks would perhaps have baulked at the sight of some of our modern 'sports'.”

It was natural that when a large a number of events was added, they could not all, as at first, take place on one day; and, indeed, it would hardly have been worth the journey from such great distances. From time to time, as new sports were added, another day was given to the festival, so that when the number was complete it generally lasted for five days, divided in such a way that the three intermediate days were devoted to the contests, the first and last to the public and private sacrifices, processions and banquets.

Pausanias on Ancient Olympic Events

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece” (c. A.D. 175): “From the time the Olympian games were revived continuously, prizes were first instituted for running, and Coroebus of Elis was the victor....And in the 14th Olympiad afterwards the double course was introduced, when Hypenus, a native of Pisa, won the wild olive crown, and Acanthus the second. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“And in the 18th Olympiad they introduced the pentathlon and wrestling....And in the 23rd Olympiad they ordained prizes for boxing...And in the 25th Olympiad they had a race of full-grown horses....And in the 28th Olympiad they introduced the pancratium and the riding race. The horse of Crannonian Crauxidas got in first, and the competitors for the pancratium were beaten by the Syracusan Lygdamus, who has his sepulcher at the stone quarries of Syracuse....And the contest of the boys was not a revival of ancient usage, but the people of Elis instituted it because the idea pleased them. So prizes were instituted for running and wrestling among boys in the 37th Olympiad. And in the 41st Olympiad afterwards they invited boxing boys....And the race in heavy armor was tried in the 65th Olympiad as an exercise for war, I think.

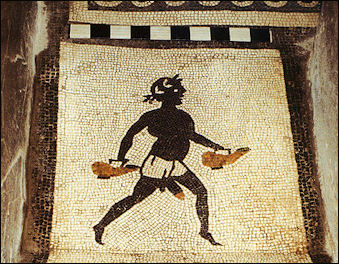

Mosaic, early AD fourth century from Tunisia, showing (from top to bottom, from the left to the right) running competition, celebration of a victor, the long jump, discus throwing, boxing, wrestling, parade of victors, pankration, a prize-table and a torch-race

“The order of the games in our day is to sacrifice victims to the god and then to contend in the pentathlon and horse-race, according to the program established in the 77th Olympiad, for before this horses and men contended on the same day. And at that period the pancrataists did not appear till night, for they could not compete sooner, so much time being taken up by the horse-races and pentathlon.”

Days and Order of Events at the Ancient Olympics

Day One: Contestants and their families began the day with a procession to Altis for oaths, sacrifices, and offerings. Athletes congregated in front of a statue of Zeus, which stood on a pedestal, holding three thunderbolts in his right hand. Below him, priests offered a sacrificial piglet while people observed the scene. Participants affirmed their Greek heritage and adherence to Olympic rules before proceeding to the Council Chamber for animal sacrifices and loyalty oaths to Zeus. [Source Adolfo Arranz and Han Huang, Reuters, August 1, 2024]

Days Two and Four: Only during the second and fourth day were the sporting competitions held, with the equestrian races being the first event of the Olympic festival. The atheltics and equestrian competitions ran from the second to the fourth day; probably the boys contended on the second, the men on the third and fourth days. We know little about the order of events; still, it is probable that on the third day the racing took place first, and in this order — long, single, and double course, then wrestling, boxing, and pancration; on the fourth day the equestrian contests, the pentathlon, and, last of all, the race in full panoply (armor). [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

There would then be several changes of locality, since the equestrian contests took place in the Hippodrome; the races, pentathlon, and other gymnastic sports in the Stadion. There was, of course, a gymnasium at Olympia, but this could not contain the multitude of spectators as well as the Stadion, and, therefore, the wrestling school and gymnasium at Olympia were used exclusively for the previous training of the competitors who came there for the contests.

Day Three: was the main festivity, which coincided with the full moon and was linked to religious events and rituals. No official competitions were held, although there were demonstrations of sports for young people. A grand procession took place inside the Altis culminating at the altar of Zeus with the sacrifice of 100 oxen. Part of the sacrificed animals was offered to Zeus and burned in a fire. The altar of Zeus reached a considerable height due to the accumulated ashes of the pyres over the years.

At the flattened top of the mound near the altar of Zeus, there was a burning fire. Priest threw remnants of meat into the flames as part of a sacrificial ritual. At the base of the mound was where were oxen or cattle were sacrificed as part of the ritual proceedings. Much of the sacrificed meat was served up in a great banquet organized for hundreds of people. It is imagined that at this nighttime feast there was a large campfire around which people gathered, eating and drinking. Vases show men carrying trays of food on their heads.

Day Five: On the final day, closing ceremonies were held to honor the victorious athletes. The awards consisted of olive branch crowns. These olive branches had been collected by a child with a golden sickle before the games begin and placed on an altar in the temple of Hera. The winning athletes marched in procession from the temple of Hera to the temple of Zeus along with several judges. There were proclaimed winners of their categories before the imposing statue of Zeus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Ancient Olympic Running Events

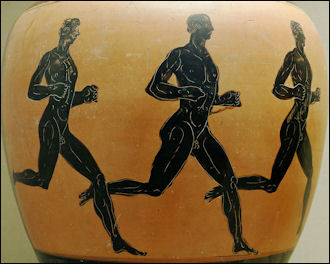

At the first Olympic held in Greece in 776 B.C. there was only one event: a 200 meter running sprint won by a cook. For the first 13 Olympics this foot races was the only Olympic event. At that time athletes gathered every four years ran naked in straight line sprint for one race that was over in about 30 seconds and the Olympic competition was over. They didn’t race again until the next Olympics four years later. Even after other events were added the 200 meter sprint remained the prestige event.

Competitors in the running events competed on a track with flat straightaways and banked curves. About 20 runners competed in a single race. The runners took “their positions, foot to foot, at the “balbis”” — a marble starting line that is still in place in Olympia’s stadium today. A trumpet call signaled the runners to take their place. They stood upright rather than crouched and were kept in line by a rope stretched across the track. After a nod from the chief judge, the herald started the race by calling out — “apate” — (go!”)

The distances for the running races were measured in stadia, the length of one stadium (193 meters). In later Olympics there were 2 stadia, 12 stadia and 24 stadia running events. The Diaulos was two laps around the stadium, covering a distance of 386 meters. The Dolichos consisted of 20 laps around the stadium, totaling a distance of 4,632 meters. The track start was marked by a narrow strip of stone slabs with parallel grooves and vertical poles that divided each runner called “balbis”. The athletes had to stand with their arms extended horizontally, in a posture very different from what we were used to seeing in running competitions today. The runners had to converge on a single turn pole. [Source Adolfo Arranz and Han Huang, Reuters, August 1, 2024]

The runners started with their toes resingt in the grooves of the balbis. Stakes separated each athlete's position, and horizontal bars adjusted between the stakes defined the starting area. The Hyplex — taut ropes or rods across the starting area — released when the start signal was given. When an athlete made a false start, they were physically punished by the judges. This punishment was also applied in other competitions for any irregularity committed by the participants. The athletes competed completely naked. Judges at the Hellanodikaion — the judge’s stand near the balbis — determined the finish. A stone strip on the ground marked the end of the race. It was up to the judges to award the prize to the winner based on a series of well-executed movements, in a way similar to how Artistic Gymnastics was judged today.

The Hoplitodromos was the final competition of the fourth day. It was another foot race and the runners were naked but they wore armor, including a helmet, shield, and bronze greaves, a considerable weight. The race was 400 metres

See Separate Article: SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Olympic Field Events

Javelin thrower The discus throw in the ancient Olympics was not all that different the discus throw in the modern Olympics except, as judged by images on vases, the throwing technique was different. The earliest surviving discuses from the 6th century B.C. were stone. Later ones were iron and bronze. The bronze models used on the A.D. 3rd century were similar to those used today. Scholars debate whether throwers used a full body rotation when they threw or gave a slight swing and relied more on arm strength.

Discus throwers did not spin around before throwing. Instead, they swung their arms holding the discus back and forth before finally throwing as far as possible. The discus was made of stone or bronze and weighed around 2.5 kilograms. Both the design and the weight of the discus was not standardized. Vases show nude athlete swinging the discus with musicians in backgroud playing flutes. [Source Adolfo Arranz and Han Huang, Reuters, August 1, 2024]

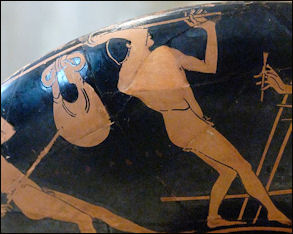

Javelin throwers used a javelin with an ankyle (leather strip) tied to the central part of the javelin, helping the athlete to throw the javelin with greater speed and force. The javelin was made of elder wood and had a bronze tip. Two fingers were put through a loop on the ankyle. While on the javelin was in the air the strap unreeled and fell off. The javelin throw probably originated as a display of hunting or battle skills. As is true today throwers competed for distance. The javelins themselves none survive. Images of them on vases indicate they were lighter and slightly shorter than modern javelins.

See Separate Article: SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Olympic Long Jumping Events

In the long jump event athletes carried halteres (stone or metal weights) in each hand that they released when making the jump. The jumpers did not take a running start to initiate the jump. They used the momentum from swinging halteres to gather impetus and jump. When landing, the athletes released the weights. The halteres had different shapes and varying weights, with a range between 1.5 and 2.5 kilograms. [Source Adolfo Arranz and Han Huang, Reuters, August 1, 2024]

Vase paintings from the 18th Olympics in 708 B.C. show athletes swinging the weights forward as they took off and swung them back behind the body as they landed. In some circles, scholars have debated whether the weights were a help or a hindrance. The event was choreographed to music. In the classical literature there were reports of Spartans jumping 50 feet. Some scholars have interpreted this as meaning that the long jump event probably consisted of several jumps. Others argue that the jumpers probably jumped a single jump and the account was exaggerated and inaccurate.

A study by Alberto Minetto, a biomechanist at Manchester Metropolitan University in Britain, holds that the weights helped the jumpers jump further. Jumping a distance depends on three things: angle, velocity and center of mass of the jumper. The weights do not affect angle or velocity but do affect the center of mass, extending it forward at the beginning of the jump, giving the jumper a boost, and extending it backwards at the end of the jump, allowing the jumper to stretch beyond where he might otherwise land as long as the weights did not significantly affect the angle or velocity of a jump

Computer models indicated the weight could increase jumps by up to two percent. Field tests using people untrained in long jumping, and using weights between two and about 20 pounds, found that the jumpers could increase their jumps by five percent, or roughly the equivalent of Bob Beamon’s world record jump in 1968 over the previous record.

See Separate Article: SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Olympics Pentathlon

The "pentathlon” consisted of a 200 meter dash, broad jump, discus throw, javelin toss and a wrestling match. Discus were often outfit with a symbol of a owl, the symbol of Athena. This event was held in the modern Olympics until 1920 and later replaced with the "modern pentathlon" consisting or running, swimming, fencing, horseback riding and shooting events.

long jumper in Pompeii mosaic The Pentathlon contests were undertaken one after another by a number of competitors, and he who did well in all of them, and took the first place in some, was declared victor in the whole. The contest consisted in jumping, running, throwing the discus, throwing the spear, and wrestling. Although the combination of these five contests was arranged with a view to the public games, yet it also had some educational importance; for difficult and easy contests were here combined, both those which required skill as well as those in which mere bodily strength carried off the palm, and thus the pentathlon was well calculated to develop the whole body harmoniously, and to keep professionals from devoting too much attention to one side of exercises to the disadvantage of the others. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

For this reason it was introduced among the exercises of the boys. We have no conclusive information about the proceedings in the pentathlon, the order in which the various contests followed one another, and the conditions on which a combatant was declared to be victorious. There is a good deal of difference of opinion among the moderns who have ventured hypotheses on the subject. One great difficulty in deciding this question arises from the fact that, though a considerable number of combatants might take part in the four first-mentioned contests, wrestling must in the nature of things be performed by only two; we must therefore assume that the contests were arranged in such a manner that only two combatants should be left for the last.

Probably they began with running, for which a considerable number could enter; supposing there were very many, they may have had several series of combats afterwards. The five best runners would then enter upon the second contest, perhaps throwing the spear; then the worst of these five would be thrown out, and the remaining four enter for the next, the jump; the three best jumpers would then throw the discus, and the two best discus-throwers would wrestle finally for the palm. Whether this or something similar was the arrangement, it might happen that a combatant who had never taken the first place in one of the first four contests might carry off the victory at last, but they avoided this by the rule that, if anyone took the first place in the first three contests or in three of the four, the two last or the last might be left out, and he would be considered victor in the pentathlon.

Consequently, the final wrestling match only took place if after the fourth contest the victory was still undecided — that is, if among the two best discus-throwers neither had taken the first place three times. It might, therefore, happen that a man who took the first place twice and the second place once in the first three contests was thrown out in the fourth, and the victory fell to another who had never taken the first place except at the last. Still, this apparent injustice was counterbalanced by the fact that the last contest was really the most difficult, while a certain average excellence in the former contests was required of everyone who entered the pentathlon at all; also it was no small merit to keep a place among the victors in all five contests, though it might not be the first or second. Of course these are merely hypotheses; we have not sufficient materials for attaining certainty in this matter.

Ancient Olympic Wrestling and Boxing Events

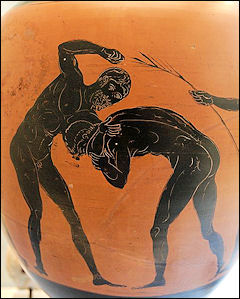

In the wrestling events there were no weight divisions or time limits. The wrestlers didn’t score points with take downs or reversals or win a matchs with a pin. The loser was the first one to touch any part his body, other than his feet, to ground three times. Wrestling was something that all free-born Greek men engaged in and was a common gymnasium activity.

Modern Olympic Greco-Roman wrestling is not really like the wrestling practiced by the ancient Greeks and Romans. The main difference between Greco-Roman wrestling and Olympic freestyle wrestling is that in the former a wrestler can not seize his opponent below the hips or grabs his legs. This means that throws have to be one by lifting an opponent above the waist, something that requires a lot of strength to do.

Greek boxers battled each other beginning in the 23rd ancient Olympics in 688 B.C. Contestants were selected for bouts by the luck of the draw. In the fights, the boxers’ hands were wrapped in leather thongs and they fought with no breaks or rounds until one fighter gave up or was knocked senseless. Blows to the body were not allowed; only blows to the head. By the end of their careers boxers had huge cauliflower ears, were missing a great number of teeth and were the butt of endless jokes in Greek comedies.

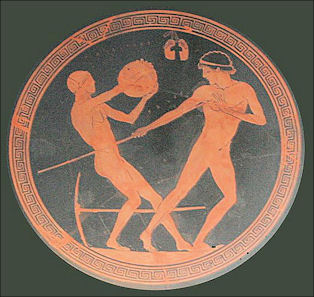

Pankration The wrestling competitions took place in a skamma — a depressed or excavated area within the stadium. In Orthia Pale (Upright wrestling) standing fighters tried to knock their opponent onto their back, hip, or shoulder. The winner was the one who managed to do this three times. The opponents started facing each other and remained standing at all times. Their body were covered in olive oil which makes gripping the fighter a great challenge. In one vase image two nude wrestlers were depicted facing each other in profile, with their heads nearly touching. They were standing upright and embracing, and trying to take down their opponent. [Source Adolfo Arranz and Han Huang, Reuters, August 1, 2024]

In Kato Pale (‘rolling’ or ‘ground’ wrestling) the athletes fought in a crouched position until one of them acknowledged defeat, a gesture performed by raising their hand with the index finger extended. Prohibitions included biting, hitting, breaking fingers, grabbing the opponent's genitals, or attempting to gouge out their eyes were not allowed. A judge was in charge of punishing those who violated the rules with a rod.

In ancient Olympics boxing the objective was to land blows on the opponent until they surrendered, a gesture made by raising the index finger, similar to the Kato Pale event. Striking the opponent was allowed even if they were on the ground. However, actions such as biting, kicking, or tripping the opponent were prohibited. The athletes wrapped their fists with himantes — strips of tanned oxhide that were wrapped around the hands and wrists to protect the knuckles, leaving the fingers free. Their function was to protect the wearer's hand, not the opponent's face. Each himante measured around four meters in length.

See Separate Article: WRESTLING AND BOXING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

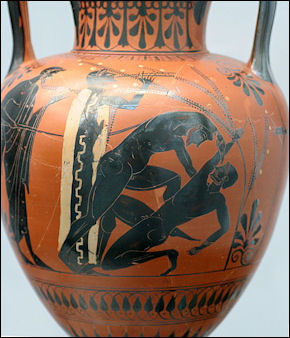

Pankration — the Marquee Ancient Olympic Fighting Event

The marquee event was the pankration. This competition combined elements of wrestling, kick boxing and murder. Strangling, kicking, slapping, bending back the fingers, tearing out an opponent’s internal organs and delivering blows to any part of the body, including the genitals, were allowed, but biting and eye gouging were prohibited. It was not unusual for losers to have shoulders and feet twisted out of socket.

No hand protections were used. Defeat was acknowledged when one of the combatants surrendered, raising the index finger. The referees carried whips. In most cases a competitor was declared the winner when his opponent either fell unconscious or held his hand up in defeat. One famous wrestler nicknamed Mr Digits specialized in breaking his opponents fingers. Killing was not allowed. If a man killed another man, the dead man was declared the winner. When a combatant was strangled to death the judges sometimes awarded him an olive crown for showing courage.

In one fabled match Damixones of Syracuse and Kreugas of Epidmanos fought for perhaps several hours with no decided winner. They then agreed to accept an undefended blow from their rival to decide the match. Kreugas went first and smashed Damixones in the head. Damixones survived. He delivered his blow to the abdomen, piercing the skin and ripping out Kreugas’s intestines and killing him. Kreugas was declared the winner. Damixones was disqualified on the ground that in the process of dismembering his opponent he delivered several blows (one from each finger) rather than the agreed upon single blow.

See Separate Article: WRESTLING AND BOXING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Olympics Chariot and Horse Racing

Chariot races with four full-grown horses was added to the Olympics in 680 B.C. In 408 B.C. the chariot race with two horses was introduced. Chariot racing was among the biggest draws at the ancient Olympics. During the races spectators were sometimes killed after they ran onto the track.

The Olympic games often kicked off with a race involving 40 chariots flying through a course at one time with spectacular spills and frequent deaths. Often only a handful of the chariots that started made it to the finish line. Chariots had to make 12 laps around the track, totalling around 13,500 meters. Competitors were often killed. Describing an accident Sophocles wrote: “As the crowd saw the driver somersault, there rose a wail of pity for the youth as he was bounced onto the ground , then flung head over heels into the sky. When his companions caught the runaway team and freed the bloodstained corpse from his reigns he was disfigured and marred past the recognition of his best friend.”

Horse races were added to the Olympics in 648 B.C. Attempts were made to introduce mules and mares, but these were soon abandoned; colts were, however, introduced for the contest with four and two horses, and also for riding. Awards were often given to the owners not the riders. When the riders were recognized both the horse and the rider were given wreaths. Equestrian sports were among the few events that women and girls were allowed to compete in.

See Separate Article: CHARIOT RACING AND HORSE RACING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Sports Excluded from Ancient Olympics

Boxers According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “At the core of Greek athletics was an individual's physical endeavor to overtake an opponent. For this reason, sports in ancient Greece generally excluded team competitions and performances aimed at setting records. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

John Fox wrote in the Los Angeles Times, Ball games and team sports “have become so integral to our very notion of sport that it would be unthinkable to host the” Olympics Games without them. “But the elevation of ball play to Olympic status is an entirely modern phenomenon. It would have been equally unthinkable in Classical times for an object as fun and frivolous as the ball to have been allowed entry to the hallowed sanctuary of Olympia. [Source: John Fox, Los Angeles Times, June 9, 2012. Fox is the author of “The Ball: Discovering the Object of the Game”.]

"More reminiscent of today's competitive team sports was episkyros, a rugby-like game played by two teams of a dozen or so players with a feather-stuffed leather ball. The 4th century playwright Antiphanes vividly described a game in progress, handing down possibly history's first play-by-play sports commentary: "He caught the ball and laughed as he passed it to one player at the same time as he dodged another ... and all the while there were screams and shouts: Out of bounds! Too far! Past him! Over his head!"

"But these entertaining games were in a class apart from the Olympics, which were regarded not as "games" — a term not associated with the events until modern times — but as agon (root of agony), serious "struggles" of body and will. Young men of worth engaged in these sacred contests as proxy and preparation for battle; the muscle-bound Olympian represented the ideal of the man prepared to defend the city-state. To win was glorious: Along with an olive wreath and lifelong admiration, victors received a lifetime annuity and exemption from taxation (so much for amateurism)."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024