Home | Category: Culture and Sports

WRESTLING IN ANCIENT GREECE

Throughout the whole of antiquity the favorite contest was wrestling, and the importance of this depended on the fact that the whole body was exercised at the same time, and all the muscles came into play; and also that it was not an exercise performed by one single man, but was an immediate measuring of strength by two opponents, and, therefore, even more than the other contests, required full bodily power. Even in the Homeric age, therefore, wrestling played an important part, and the deep hold it took on Greek life is shown by the great number of technical expressions taken from wrestling which in metaphorical form found their way into the ordinary every-day language; no other exercise had so large a store of technical expressions; indeed, it is absolutely impossible for us to find words to express them all at the present day. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

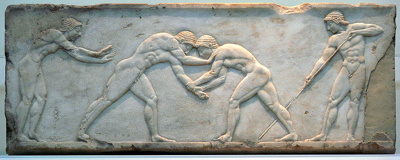

There were two principal methods in ordinary wrestling — standing and ground wrestling. In the first kind of contest everything depended on throwing an opponent, either by skill, or by certain tricks which were allowed in wrestling, in such a way that his shoulder touched the earth, while the other kept his position; throwing once, however, did not decide the victory, but in order to be victorious in the standing wrestling-bout it was necessary for a man to throw his opponent three times in this manner. When both opponents fell together while wrestling without clasping each other, they jumped up and began the contest afresh; but if they grasped each other firmly when they fell, so that the contest was not yet decided, the wrestling usually passed into the second stage, in which both wrestled while lying on the ground, when now one now the other might get the advantage, until one of the two declared himself conquered, and gave up the struggle.

The wrestlers in the celebrated Florentine marble group are in this position. This wrestling on the ground, however, only took place in the boys’ gymnastic school, and afterwards in the public contests of Pancratiasts, and professional athletes; in the great contests and the Pentathlon only standing wrestling was allowed. The mode in which the wrestlers began the combat has been clearly described by several writers, and often represented on monuments. Each combatant took his place, with his legs somewhat apart, his right foot forward, stretched out his arms, drew his head a little between his shoulders, and thrust forward the upper part of his body, back, shoulders, and neck, in order to protect the lower part somewhat from the attack of his opponent. In this manner the combatants stepped towards each other, each watching for the moment when the other would expose himself in some way of which he could take advantage, and as they were naturally both as much as possible on their guard, it was often a considerable time before they could begin the contest by seizing hold of their opponents. But when it was once begun, the masters or other officials who superintended watched to see that no tricks contrary to tradition and rule were made use of, that there was no striking or biting; but still, they were allowed to make use of certain tricks or feints in order to deceive the enemy or gain an advantage over him.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SPORTS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK SPORTS FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

FESTIVALS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE OLYMPICS: ORIGIN, MYTHS, OLYMPIA, REBIRTH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK OLYMPICS: WHAT THEY WERE LIKE, ATMOSPHERE, PURPOSE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES: TRAINING, NUDITY, WINNERS AND CHEATERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMOUS ANCIENT OLYMPIC ATHLETES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT OLYMPIC EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece: Modern Fighting Techniques from the Age of Alexander” by Kostas Dervenis, Nektarios Lykiardopoulos (2007) Amazon.com;

“Pankration: The Unchained Combat Sport of Ancient Greece” by Jim Arvanitis (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Athletics” by Stephen G. Miller (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Crown Games of Ancient Greece: Archaeology, Athletes, and Heroes” by David Lunt (2022) Amazon.com;

“Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens” (2004) Amazon.com;

“Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World” by David Phillips and David Pritchard | (2003) Amazon.com;

“Arete: Greek Sports from Ancient Sources” by Stephen G. Miller (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Running: Learning to Run Like a Greek” by Andrea Marcolongo (2024) Amazon.com;

Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics” by David Stuttard (2012) Amazon.com;

“Greek Athletics and the Olympics” by Alan Beale (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympic Games” by Judith Swaddling (1980) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Olympics: A History” by Nigel Spivey (2004) Amazon.com;

“Olympia: The Story of the Ancient Olympic Games” by Robin Waterfield (Landmark) (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years” by Moses Finley (1968, 2005) Amazon.com;

Wrestling Rules in Ancient Greece

Among the methods allowed was throttling, either by touching the opponent’s neck or throwing an arm round it, or pushing the elbow under his chin, and sometimes the combatant who was attacked in this way was forced from want of breath to declare himself conquered, even without being thrown; similarly his opponent might force him, by pressing his body together to abandon the contest; and in the ground wrestling it sometimes happened that the combatant who had the upper hand knelt down on the one who had been thrown to the ground and throttled him until he asked for mercy. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

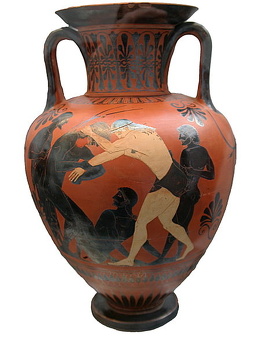

Twisting and bending the limbs was also allowed, thrusting an arm or a foot into the opponent’s belly, pushing or forcing him from the spot, which, if the hands were occupied, was often done by means of the forehead, the two combatants dashing their heads against each other like two angry bulls; this was a very favorite trick, and is frequently shown on works of art. In another image, taken from a vase painting we see two wrestlers who have grappled, each holding his opponent’s right arm with his own left; their foreheads are pressed together, one has drawn back his right foot in order to increase his resisting power. The combatants, are fighting in a similar manner, the left hand of one seizes the right arm of his opponent, while his right arm is thrown round his body; the left hand of the other Meanwhile attacks his enemy’s back. On the left a superintendent, who wears a cloak, and holds a branch in his hand, stands looking on; on the right a young man is running quickly away.

Among the permitted feints was a sudden thrust of the leg, which hit the opponent’s knee from behind with the foot in such a manner as to throw him, or, if this was impossible, a similar blow was attempted on the side; they also seized an opponent by the leg or ankle in such a way as to lift it from the ground with a violent impulse, so that he must fall backwards. Sometimes a strong and skilful wrestler would put his arms round his opponent’s hips in such a way as to lift him entirely from the ground, and turn him over with his head downwards. On one vase painting one of the wrestlers has lifted up his opponent in this manner, and the latter is trying to free himself from the arms which are holding him. In the other group, one of the wrestlers with his right arm seizes the left arm of his opponent and tries to press him down with his body, thrusting his head over the left shoulder of the other; the latter, however, thrusts his head over his opponent’s back, and with his right arm seizes his opponent’s right arm from behind. The richly-clad youth standing by presents an almost feminine appearance, holding a staff and flower in his hands, and it is not clear for what purpose he is there. Similar tricks and manoeuvres were used in ground wrestling. Besides this they also attempted to entangle the opponent’s legs in theirs, in order to prevent him from standing up again. There were a great many similar modes or plans of wrestling, all with a special terminology, and it seems as though no gymnastic exercise had been so thoroughly developed into a real art as that of wrestling.

Oiling and Bathing Practices of Ancient Greek Wrestlers

Wrestling, like other athletic exercises, was carried on at first with some drapery round the loins, and afterwards without any clothing. As a preparation, the combatants rubbed their whole bodies with oil, with a view to making their limbs more supple and elastic. For this purpose there were special rooms in the gymnasia and wrestling schools, in which stood large vessels, filled with oil, from which they filled their own little flasks; then they poured a little oil out of these into their hands, and either rubbed their bodies with it or else had them rubbed by one of the attendants of the gymnasia appointed for the purpose. But as this oiling and the perspiration which resulted from the contest would have made the body too smooth and slippery, and absolutely impossible to grasp, they covered themselves, when the anointing was finished, with fine dust, taken from special pits, or else prepared on purpose. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

This was supposed also to serve a hygienic purpose, for it was assumed that the dust prevented excessive perspiration, and in consequence saved the strength; it was also regarded as advantageous because it closed the pores and sheltered them from the air, which might have an injurious effect. Oil, perspiration, dust, and also the soft sand, which, when the wrestlers continued their contest on the ground, clung to their bodies, together formed a thick crust, which could not have been sufficiently removed by a mere warm bath; therefore the wrestlers used a stlengis, or strigil, for cleansing their bodies, rubbing off the dirt partly themselves and partly with the help of attendants, and afterwards took a warm bath. The action of this scraping, which, in spite of its unaesthetic nature, gave rise to many graceful attitudes, has been often plastically represented by artists; a good copy has come down to us of the most celebrated of these figures, the Apoxyomenos of Lysippus.

The bath was usually followed by oiling the body once more, because the use of oil was regarded as good for the health and tending to strengthen the limbs. As already mentioned, this anointing was accompanied by a kind of massage, a pressing and kneading of the body, which the rubber understood, and which was regarded as a hygienic method, so that one who was specially skilled in it was called a medical-rubber, and in a measure combined the duties of physician and rubber. The constant exposure to fresh air and accustoming of the naked body to the rays of the sun, combined with the oiling and dusting mentioned above, produced in the wrestlers especially, though to some extent in all the athletes, a very dark complexion, which the ancients regarded as a mark of health and of manly courage, and often held up to admiration in contrast to the pale colouring of the artisans and stay-at-homes who “sat in the shade.”

Boxing in Ancient Greece

Boxing, which we hear of among the funeral games in honour of Patroclus, was also practised in the historic period, but as a mode of fighting it was not actually necessary for the athletic training of every Greek, but was rather studied by those who desired to win prizes in the public games, and to obtain honour and reward by their bodily skill and strength. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We are accustomed to regard the athletic training of the Greeks as tending not only to the development of the body, but also to that of the mind; and we cannot deny that boxing, especially in the form which it assumed in the course of centuries, was a rough sport, and that the pleasure which the Greeks undoubtedly took in watching it, though not quite of so degrading a nature as the cruel delight taken by the Romans in the fights of gladiators and wild beasts, yet, considered in connection with certain other popular sports, such as cock-fighting, must be taken as a sign that even the high degree of culture, which the Athenians had undoubtedly attained by the fifth century, was not quite sufficient to suppress completely the animal instinct in man. After all, our much-lauded nineteenth century is not unacquainted with such amusements as boxing, pigeon-shooting, and similar sports.

As early training method in boxing, especially in learning the commonest attacks and parries, they used a bladder or leather ball, hung up and filled with sand; this exercise is often represented on old monuments, and most clearly on the so-called “Ficoronese Cista.” This striking at the ball was one of the regular contests in the gymnasium, for though the dangerous fighting with the leaded thongs was left to professional athletes, yet a trial of skill in the commoner kind of harmless boxing, in which there was no risk of losing teeth, etc., was a very favorite practice, and this, no doubt, is meant when we find boxing mentioned even among the athletic exercises of boys.

Boxing Rules in Ancient Greece

Boxing, like wrestling, was subject to special rules, from which we see that more stress was laid on artistic and elegant methods than on the mere evidence of great bodily strength and rude force. Specially skilful boxers, indeed, devoted themselves chiefly to wearing out their enemy by keeping strictly on the defensive — that is, parrying all his blows with their arms, and thus forcing him at last to give up the contest, rather than making him unfit to fight by well-aimed blows. They distinguished, too, in the defensive between correctly-aimed blows and mere rough hitting, which sometimes gave a combatant the victory if he happened to possess considerable strength, but by no means won reputation for him. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

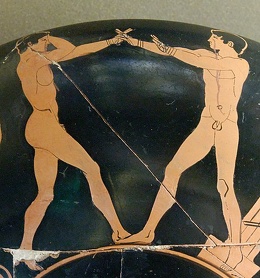

For the contest they generally took their position in such a manner as not to turn their whole body to the enemy, but only one side, and, as a rule, the left. It was in the nature of the contest that a constant change between attack and defence must take place; the attitude represented on numerous monuments, in which the left arm is used for parrying, the right for attack, was the common one, not only as an opening, but repeated at each new phase, though a change would sometimes take place, and the right arm be used in defence, the left for attack.

On one vase painting we see two boxers, whose huge proportions show that they were endowed with unusual strength; both have covered their arms and hands with heavy thongs, one is apparently countering with the left, the other parrying with the right; his left aims at his enemy’s head. On the right stands a winged Goddess of Victory, on the left a boxer with the thongs, raising his left arm to his head. The vase painting, represents two boxers, one of whom aims a well-directed blow with his left at the breast of the other, who totters. On one side lie some poles, as well as implements belonging to the wrestling school, strigil, sponge, etc. In another the boxer one to the right has “got home” so effectively on the head with his left, that the other, who has tried to guard with his left arm, has to give ground, and seems to have had enough, for he is raising the first finger of his right hand, a sign that he begs for mercy and declares himself conquered. The thongs here are only worn on the right hand of one of the combatants, but this was probably merely an omission on the part of the painter.

Boxing Injuries in Ancient Greece

All the same, severe bodily injuries, or, at any rate, lasting deformities, especially in the head and face, were inevitably connected with boxing, and it was by no means unusual for boxers to have their ears completely disfigured and beaten quite flat, and, indeed, we see this on some of the ancient heads; afterwards it became customary to use special bandages for protecting the ears. A practice which made boxing especially rough, and sometimes even dangerous to life, was that of covering the hands with leathern thongs. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Originally these thongs were tolerably harmless; they consisted merely of leather, and were put on in such a way that the fingers remained free, while the thongs extended a little way above the wrist and covered part of the lower arm — of course, in such a way as not to check the motion of the hand. But this gentler kind, which were still capable of inflicting rather serious injuries, were afterwards in use only for the early training method before a serious contest; for the latter they used heavy boxing-gloves of hardened bull’s hide, into which knobs of lead, etc., were worked. We can easily imagine what terrible wounds might be inflicted by a blow from one of these.

Many of the old athletes could show bodies covered with wounds like that of an old soldier, and the writers of epigrams laughingly compared the bodies of athletes to sieves full of holes. And although they were forbidden purposely to give blows which threatened the life of an opponent, yet it sometimes happened, as in the notorious contest between Creugas and Damoxenus, that in the excitement of the moment the combatants forgot the established rules, and the professional contest turned into mere brutality, from which those of the spectators whose feelings were of a less coarse nature turned away with horror.

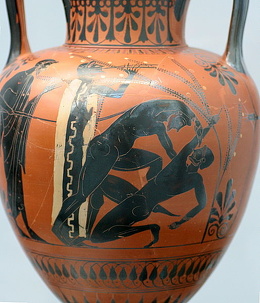

Pancration

The Pancration was a combination of boxing and wrestling. It was a difficult and dangerous sport, unknown to the heroic age. Although it was included among the exercises of the boys and youths, it was only of real importance for professional athletes. Here all the parts of the body came into play, tricks and cunning feints to lead an opponent astray were permissible, and as important as bodily strength and powerful fists. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The combatants fought naked, like the wrestlers, after oiling and strewing dust over their bodies; but they did not use thongs, which would have been in the way in wrestling, nor were they permitted to strike with the whole fist, but only with the bent fingers. They began the fight standing, as in wrestling, and the special difficulty was, in taking the offensive, to avoid being seized by an opponent as well as to parry an unexpected blow from his fist.

Blows were dealt not only in the standing fight, but also in the ground wrestling, and in the pancration they made even more use of their feet for hitting and kicking than in the separate contests in wrestling and boxing; they also tried to twist their opponent’s hands and break his fingers, since the main object was to make him incapable of fighting. It is, therefore, natural that among professional athletes the pancration was regarded as the most important of all modes of fighting.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024