Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

ROLES OF WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME

Women in ancient Rome held very few rights and by law were considered not equal to men. They rarely held any public office or positions of power; instead they were expected to looking after their children and taking care of after the home. Most women in Roman society were controlled by either their father or husband. Especially among the wealthy, women and young girls were married off in order to form political or economic unions, and rarely could choose their partner. Against these odds, a few exceptional women who managed to attain great power and influence in ancient Rome. While did this drom behind the scenes; others manipulated public sentiments and were involved in conspiracies and even assassination plots to seize control of the Roman empire. [Source Live Science, October 23, 2021

Roman women were expected to serve their husbands, and perform duties that slaves did: fetch water, cook, weave. They weren't supposed to drink. Cato said the reason men kissed women on the cheek was to make sure they hadn't been drinking.

The stereotype of upper class Roman women was not all that different from stereotype of their modern upper class counterparts. Some spent the morning putting on make-up and choosing the right dress and spent the afternoon shopping and organizing the household for a dinner party.

Women were able to gain larger more power and freedom by having children. According to PBS, about half of Rome's children died before they reached the age of 10, and 1 in 4 babies didn't make it past their first year. So, mothers who had at least three living children were recognized by the government as "legally independent." [Source: BuzzFeed, September 20, 2023]

RELATED ARTICLES:

WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME: STATUS, INEQUALITY, LITERACY, RIGHTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT ROME: LAWS, TYPES, TRADITION factsanddetails.com ;

WEDDINGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LOVE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DIVORCE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Book: "Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity" by Sarah Pomeroy, a classics professor at Hunter College in New York; “The Roman Mother” (1988), “The Roman Family” (1992) and “Reading Roman” Women (2001) by Suzanne Dixon

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women And Marriage During Roman Times” (2010) by Maurice Pellison (1897) Amazon.com;

“Imperial Women of Rome: Power, Gender, Context” by Mary T. Boatwright (2021) Amazon.com;

“Women and Politics in Ancient Rome” by Richard A. Bauman (1994) Amazon.com;

“A Place at the Altar: Priestesses in Republican Rome” by Meghan J. DiLuzio Amazon.com;

“Vestal Virgins, Sibyls, and Matrons: Women in Roman Religion”

by Sarolta A. Takács (2022) Amazon.com;

“Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher” by Edward J. Watts (2017)

Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Rome” by Paul Chrystal (2013) Amazon.com

“Women in Ancient Greece and Rome” (Cambridge Educational) by Michael Massey (1988) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of Women in Ancient Rome” (Greenwood Press) by Sara Elise Phang (2022) Amazon.com;

“A Week in the Life of a Greco-Roman Woman” by Holly Beers Amazon.com;

“Women and the Law in the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook on Marriage, Divorce and Widowhood” (Routledge) by Judith Evans Grubbs (2002) Amazon.com;

“Women in Roman Law and Society” by Jane F. Gardner (1991) Amazon.com;

“I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome” by E. E. Kleiner (1996) Amazon.com;

“Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation” by Maureen B. Fant and Mary R. Lefkowitz (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Missing Thread: A Women's History of the Ancient World” by Daisy Dunn (2024) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Women & Society in Greek & Roman Egypt” by Jane Rowlandson (1998) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Married Women and Guardians in Ancient Rome

By the marriage cum manu a Roman woman escaped the manus of her father and his male relations only to fall into the manus of her husband. The marriage sine manu made her the ward of a so-called "legitimate guardian" who had to be chosen from among her male relations if the direct male line of her progenitors had died out. When, however, the marriage sine manu had completely supplanted the cum manu marriage, the "legitimate guardianship" which had been its inseparable accompaniment began to lose its importance. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

By the end of the republic, a ward who chose to complain of the absence of her guardian however short that absence might have been was able to get another appointed for her by the praetor. When, at the beginning of the empire, the marital laws which are associated with the name of Augustus were passed, the "legitimate guardians" were sacrificed to the emperor's desire to facilitate prolific marriages, and mothers of three children were exempted from guardianship.

In Hadrian's day a married woman did not need a guardian even to draft her will, and a father no more dreamed of forcing his daughter to marry against her will than of opposing a marriage on which she had set her heart, for, as the great jurist Salvius lulianus maintained, a marriage could not be made by constraint, but only by consent of the parties thereto, and the free consent of the girl was indispensable.

Virtuous Women in Ancient Rome

Rape of Lucretia

Suzanne Dixon wrote for the BBC: “We know of good women from literature, legend, coins and statues but, above all, from the many epitaphs that have survived from Roman Italy - such as the following, concerning 'Claudia'. |“'Stranger, my message is short. Stop and read it. This is the unlovely tomb of a lovely woman. Her parents gave her the name Claudia. She loved her husband with all her heart. She bore two children, one of whom she left on earth, the other beneath it. She had a pleasing way of talking and walking. She tended the house and worked wool. I have said my piece. Go your way.' (Corpus of Latin Inscriptions, CIL 6.15346) [Source: Suzanne Dixon, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

Bereaved Romans often praised their mothers, wives and daughters on their tombstones, although their words were usually much briefer than this famous epitaph from Italy in the late second century B.C. Often, however, they did echo the key feminine virtues mentioned in the epitaph, those of affection, good housewifery and chastity. Wool work was very much a symbol of a good woman. |::|

“Every Roman schoolchild also learned the story of another good woman, Lucretia, who attracted the unwelcome attentions of a tyrant by her beauty and her domestic industry (working late at night at the loom). Her rape and subsequent suicide was said to be the origin of the Roman revolt against the Etruscan monarchy, and the foundation of the Roman Republic in 509 B.C. The story is told by the historian Livy in his first book (late first century B.C.). |::|

“Augustus instigated the practice of holding up the women of the imperial family as inspiring models of virtuous womanhood in the first century AD. Later emperors carried it further and in the second century A.D. empresses such as Sabina (wife of the emperor Trajan) were depicted as embodying, for example, pietas (family feeling). Faustina the younger, wife of Marcus Aurelius, often featured on coins symbolising various virtues, while Marcus's daughter-in-law, Lucilla, was particularly associated with modesty. Letters and epitaphs tell of the particular grief of Roman parents if a girl died before marriage - and they seem truly to have delighted in their living daughters. The first and second century writer Pliny the Younger (Letter 5.16) paints a touching portrait of his friend's daughter, Minicia Marcella, who died at the age of 13. |::|

Pliny the Younger mentions among his own acquaintance some whose love for their husbands prompted them to die with them. I was sailing in a boat [he writes] on the Lake of Como, when an older friend called my attention to a villa... which projects into the lake. "From that room," he said, "a woman of our city once threw herself and her husband." I asked why. Her husband was suffering from an ulcer in those parts which modesty conceals. His wife begged him to let her see it, for no one could give him a more honest opinion whether it was curable. She saw it, gave up hope, and tying herself to her husband she plunged with him into the lake. [Source:“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Admirable, Self-Sacrificing Women in Imperial Rome

The close of the first century and the beginning of the second include many women of strong character, who command our admiration. Empresses succeeded each other on the throne who were not unworthy to bear at their husband's side the proud title of Augusta which was granted to Livia only after her husband's death. Plotina accompanied Trajan through the Parthian wars and shared alike his glories and responsibilities. When the optimus princeps lay at death's door, having only in secret appointed Hadrian to succeed him, it, was Plotina who interpreted and reinforced his last wishes; and it was she who ensured that Hadrian enter in peace and without disturbance on the sovereign succession of the dead emperor. Hadrian, who is wrongly supposed to have been on bad terms with her, carefully surrounded her with so much deference and gracious consideration that the ab epistolis Suetonius forfeited overnight his "Ministry of the Pen" for having scanted the respect due to her. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The great ladies of the aristocracy in their turn were proud to recall as immortal models the heroines of past evil reigns who, having been the trusted confidantes of their husbands, sharing their commands and their politics, refused to be parted from them in the hour of danger and chose to perish with them rather than leave them to fall uncomforted under the tyrant's blow. When Nero sent Seneca the fatal command to kill himself, the philosopher's young wife Paulina opened her veins together with her husband; that she did not die of haemorrhage like him was solely because Nero heard of her attempt to commit suicide and sent an order to save her life at any cost; she was compelled to let them bandage her wrists and close the wounds. The record which the Annales have preserved for us of this moving scene, the portrait they paint of the sad and bloodless face of the young widow who bore to her dying day the marks of the tragedy, express the deep emotion which the memory of this drama of conjugal love still inspired in the Romans of Trajan's day after the lapse of half a century.

Tacitus felt great admiration for the loyalty of Paulina.At first her son-in-law Thrasea sought to dissuade her. "What," he said, "should you agree, if I were one day to die, that your daughter should perish with me?" Arria would not allow her stern resolution to be weakened. "If my daughter in her turn had lived as long with you and in the same happiness as I with Paetus, I should consent," she said. To cut the argument short she flung herself headlong against the wall and fell unconscious to the ground. When she came to herself she said: "I warned you that I should find some road to death, however difficult, if you refused to let me find an easy one." When the fatal hour at last arrived she drew a dagger from her robe and plunged it in her breast. Then, pulling the weapon out again, she handed it to her husband with the immortal words: "It does not hurt, Paetus."

Roman Women Who Enjoyed Hunting, Sports and Partying

But the outdoor types arouse even more ridicule than the blue stockings. If Juvenal were alive today he would be pretty sure to shower abuse on women drivers and pilots. He is unsparing of his sarcasm for the ladies who join in men's hunting parties, and like Mevia, "with spear in hand and breasts exposed, take to pig-sticking' and for those who attend chariot races in men's clothes, and especially for those who devote themselves to fencing and wrestling. He contemptuously recalls the ceroma which they affect and the complicated equipment they put on the cloaks, the armguards, the thighpieces, the baldrics and plumes. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

"Who has not seen one of them smiting a stump, piercing it through and through with a foil, lunging at it with a shield and going through all the proper motions?... Unless indeed she is nursing some further ambition in her bosom and is practising for the real arena." Some, perhaps, who today admire so many gallant female "records" will shrug their shoulders and accuse Juvenal of poor sportsmanship and narrow-mindedness. We must at least concede that the scandal of his times justified the fears which he expressed in this grave query: "What modesty can you expect in a woman who wears a helmet, abjures her own sex, and delights in feats of strength?"

For three hundred years women had reclined with their husband at the banquets. After they became his rival in the palaestra, they naturally adopted the regimen of an athlete and held their own with him at table, as they disputed the palm with him in thearena. Thus other women, who had not the excuse of sport, also adopted the habit of eating and drinking as if they took daily exercise. Petrohius shows us Fortunata, the stout mistress of Trimalchio, gorged with food and wine, her tongue furred, her memory confused, her eyes bleared with drunkenness. The great ladies or the women who posed as such on the strength of their money-bags whom Juvenal satirizes, unashamedly displayed a disgusting gluttony. One of them prolongs her drinking bouts till the middle of the night and "eats giant oysters, pours foaming unguents into her unmixed Falernian... and drinks out of perfume bowls, while the roof spins dizzily round and every light shows double." Another, still more degraded, arrives late at the cena, her face on fire,and with thirst enough to drink off the vessel containing full three gallons which is laid at her feet and from which she tosses off a couple of pints before her dinner to create a raging appetite; then she brings it all up again and souses the floor with the washings of her insides.... She drinks and vomits like a big snake that has tumbled into a vat. The sickened husband closes his eyes, and so keeps down his bile.

Working Women in Ancient Rome

Suzanne Dixon wrote for the BBC: Although there were specialist cloth shops, all women were expected to be involved in cloth production: spinning, weaving and sewing. Slave and free women who worked for a living were concentrated in domestic and service positions - as perhaps midwives, child-nurses, barmaids, seamstresses, or saleswomen. We do, however, have a few examples of women in higher-status positions such as that of a doctor, and one woman painter is known. [Source: Suzanne Dixon, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

“How do we know about women's work? From men saying in print what women should be doing - poets (like Virgil), and philosophers (like Seneca), and husbands praising their dead wives on tombstones not only for being chaste (casta) but also for excelling at working wool (lanifica). |We can also learn about women's work from pictures on vases and walls (paintings), or from sculptural reliefs on funerary and public art. Septimia Stratonice was a successful shoemaker (sutrix) in the harbour town of Ostia. Her friend Macilius decorated her burial-place with a marble sculpture of her, on account of her 'favours' to him (CIL 14 supplement, 4698). Graffiti such as the ones on the wall of a Pompeian workshop record the names of women workers and their wool allocations - names such as Amaryllis, Baptis, Damalis, Doris, Lalage and Maria - while other graffiti are from women workers' own monuments, usually those of nurses and midwives (see CIL 14.1507). Women's domestic work was seen as a symbol of feminine virtue, while other jobs - those of barmaid, actress or prostitute - were disreputable. Outside work like sewing and laundering was respectable, but only had a low-status. Nurses were sometimes quite highly valued by their employers/owners, and might be commemorated on family tombs.” |::|

See Separate Article: LABOR, JOBS AND WORK IN THE ROMAN ERA europe.factsanddetails.com

Educated and Literate Women in Ancient Rome

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Excavations at Pompeii revealed a remarkable portrait of Terentius Neo, a "middle-class" baker, with his wife. In the fresco the baker’s wife is shown holding a stylus and wax tablet. Her accessories suggest that she is educated and literate and while portraying herself this way may have been an attempt to affect affluence and education, the fact that she is shown in this way suggests that it was, at least, possible that an ancient woman was literate. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, May 30, 2020]

The prison diary or memoir of one of Christianity’s most famous martyrs, Perpetua of Carthage, forms the foundation for the account of her suffering and death. The story explicitly mentions that Perpetua wrote the autobiographical portion of the account with her own hand. The narrator also describes her as “liberally educated,” a phrase used by Romans to refer to the broad education of elites (rather than lower status specialist education of, say, bankers). There are some good reasons to wonder if Perpetua herself actually wrote the text attributed to her, but if she did, the fact that her statements in court show hints of philosophical and rhetorical training and the records of her visions include allusions to classical mythology suggests that she was, indeed, well educated.

Pliny the Younger would certainly have appreciated woman's erudition, if we remember the praise he bestows on Calpurnia and the enthusiasm he expresses for the education and good taste of the wife of Pompeius Saturninus, whose letters were so beautifully phrased that they might pass for prose versions of Plautus or Terence. Juvenal, on the other hand, like Moliere's good Chrysale, could not endure these "learned women." He compares their chatter to the clashing of pots and bells;he abhors these "prtcieuses" who reel off the Grammar of Palaemon, "who observe all the rules and laws of language," and adjures his friend: "Let not the wife of your bosom possess a style of her own.... Let her not know all history; let there be some things in her reading which she does not understand." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Ancient Roman Women as Sex Objects and Adulterous Wives

Suzanne Dixon wrote for the BBC: “Roman poetry is the main basis for (mis)information about adulterous Roman wives or glamorous mistresses. Propertius (who flourished 30-20 B.C.), Tibullus (48-19 B.C.) and Ovid (43 BC-AD 17) wrote love poems in the first person, each about a named mistress, following the lead of Catullus (c.84-54 B.C.), who had written short lyric poems about 'Lesbia'. These poems are set in a kind of fantasy world, and had a great influence on later European poetry. |[Source: Suzanne Dixon, BBC, March 29, 2011 |::|]

“To give just a flavour of his style, perhaps the most famous poem (LXXXV) by Catullus is: 'I hate you and I love you. Perhaps you ask how I can? I don't know, but I feel it to be true and I am in torment.' Scholars have speculated that the 'Lesbia' he addressed in some poems was the elegant widow Clodia, who was attacked by the orator Cicero in court (in his defence of Caelius, 56 B.C.) for her loose living, but I think that is wishful thinking. |::|

“Ovid's delightful short poem about a rendezvous with the imaginary 'Corinna' in the evocative half-light of the afternoon has inspired many poets. Marlowe's version is great poetry, and a good rendering of the Latin. Here is an extract: 'In summer's heat and mid-time of the day To rest my limbs upon a bed I lay ... Then came Corinna in her long loose gown, Her white neck hid with tresses hanging down ... Stark naked as she stood before mine eye, Not one wen in her body could I spy. What arms and shoulders did I touch and see, How apt her breasts were to be pressed by me, How smooth a belly under her waist saw I, How large a leg, and what a lusty thigh. To leave the rest, all liked me passing well; I clinged her naked body, down she fell: Judge you the rest, being tired she bade me kiss; Jove send me more such afternoons as this!’ [Source: Ovid, Loves (Amores) 1.5] |::|

The second-century satirist Juvenal devoted his longest poem to the horrors of marriage. It is a gallery of awful married women whose vices (such as body-building and correcting their husbands' grammar) include committing adultery with men, women and even donkeys! It's racy reading, but not exactly reportage. |::|

“At a pithier level, the eruption of Vesuvius over Pompeii in A.D. 79 caused a whole range of everyday comments about women to be preserved, although needless to say we don't have the women's version of the stories uncovered there. We have a graffito from a Pompeian workshop which describes the cloth-worker Amaryllis in lewd terms. And a famous exchange on a pub wall records some banter between a weaver, Successus, and his mate, Severus, over the unrequited passion of Successus for the lovely barmaid Iris (Corpus of Latin Inscriptions, CIL 5.1507; 4.8259). Less romantically, a customer at another pub claimed to have made love with the landlady (CIL 4.8442). |::|

“Other depictions of women can be seen in the various erotic paintings on Pompeian walls. Some of these paintings are apparently in-house advertising in brothels, and others are simply for domestic entertainment. Certainly Roman men attended brothels or frequented streetwalkers, while most prostitutes would have been slaves, and doubtless had short and miserable lives. It is known for sure that married men and women had affairs - even after the emperor Augustus made them illegal. But the Roman orgy is a modern invention (not even Juvenal thought of such a thing). Sorry if that's a disappointment. |::|

Concubines in Ancient Rome

Michael Van Duisen wrote for Listverse: “A concubine in ancient Rome was slightly different from that of the traditional variety. First off, a man could only have one concubine at a time, and was not allowed to have a concubine if he was already married. In addition, the relationship between a man and his concubine had legal standing and was considered a step below marriage, though there were specific legal differences. [Source: Michael Van Duisen, Listverse, February 13, 2014]

“In fact, most women who became concubines were only not wives due to social standing, or a man’s wish not to complicate the inheritance of his wealth due to a previous marriage. Children born from concubinage were considered illegitimate; however, the father was still expected to provide for them while he was alive. Also, the concubine herself was not elevated to the same social status as the man—as opposed to a wife—and she was banned from worshiping Juno, the goddess of marriage.

Edward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: A concubine, in the strict sense of the civilians, was a woman of servile or plebeian extraction, the sole and faithful companion of a Roman citizen, who continued in a state of celibacy. Her modest station, below the honors of a wife, above the infamy of a prostitute, was acknowledged and approved by the laws: from the age of Augustus to the tenth century, the use of this secondary marriage prevailed both in the West and East; and the humble virtues of a concubine were often preferred to the pomp and insolence of a noble matron. In this connection, the two Antonines, the best of princes and of men, enjoyed the comforts of domestic love: the example was imitated by many citizens impatient of celibacy, but regardful of their families. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part IV, “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

If at any time they desired to legitimate their natural children, the conversion was instantly performed by the celebration of their nuptials with a partner whose faithfulness and fidelity they had already tried. By this epithet of natural, the offspring of the concubine were distinguished from the spurious brood of adultery, prostitution, and incest, to whom Justinian reluctantly grants the necessary aliments of life; and these natural children alone were capable of succeeding to a sixth part of the inheritance of their reputed father. According to the rigor of law, bastards were entitled only to the name and condition of their mother, from whom they might derive the character of a slave, a stranger, or a citizen. The outcasts of every family were adopted without reproach as the children of the state.

Laws Pertaining to Concubines in Ancient Rome

The following are some laws pertaining concubinage from the Corpus Iuris Civilis [The Code of Civil Law] produced in the A.D. 530s by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian' (A.D. 482-566). The texts here date back particularly to the time of Augustus [ruled 27 B.C. - A.D. 14] who was very concerned about family matters and ensuring a large population. The selections comes from a digest that contain the opinions of famous lawyers - Marcianus, Paulus, Terentius Clemens, Celsus, Modestinus, Gaius, Papinianus, Marcellus, Ulpianus, and Macer.

Book XXVI. Title VII. Concerning Concubines: Ulpianus, On the Lex Julia et Papia, Book II. Where a freedwoman is living in concubinage with her patron, she can leave him without his consent, and unite with another man, either in matrimony or in concubinage. I think, however, that a concubine should not have the right to marry if she leaves her patron without his consent, since it is more honorable for a freedwoman to be the concubine of a patron than to become the mother of a family. 1) I hold with Atilicinus, that only those women who are not disgraced by such a connection can be kept in concubinage without the fear of committing a crime.... 3) If a woman has lived in concubinage with her patron, and then maintains the same relation with his son or grandson, I do not think that she is acting properly, because a connection of this kind closely approaches one that is infamous, and therefore such scandalous conduct should be prohibited. 4) It is clear that anyone can keep a concubine of any age unless she is less than twelve years old. [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329] [Lex Julia is an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the Julian family. Most often it refers to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 B.C., or to a law from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar]

Paulus, On the Lex Julia et Papia, Book XII: Where a patron, who has a freedwoman as his concubine, becomes insane, it is more equitable to hold that she remains in concubinage. Opinions, Book XIX: The woman must be considered a concubine even where only the intention to live with her is manifested., Opinions, Book II: An official who is a resident of the province where he administers the duties of his office can keep a concubine....Modestinus, Rules, Book I: Where a man lives with a free woman, it is not considered concubinage but genuine matrimony, if she does not acquire gain by means of her body.

Marcianus, Institutes, Book XII: The freedwoman of another can be kept in concubinage as well as a woman who is born free, and this is especially the case where she is of a low origin, or has lived by prostitution; otherwise if a man prefers to keep a woman of respectable character and who is free born in concubinage, it is evident that he can not be permitted to do so without openly stating the fact in the presence of witnesses; but it will be necessary for him either to marry her, or if he refuses, to subject her to disgrace. 1) Adultery is not committed by a party who lives with a concubine because concubinage obtains its name from the law, and does not involve a legal penalty; as Marcellus states in the Seventh Book of the Digest.

Juvenal Misogynist View of Roman Women

William Stearns Davis wrote: “About 100 CE. a keen and bitter satirist delivered himself as follows against the women of Rome. Some of his charges are clearly overwrought; but there is no doubt that the Roman ladies often abused the very large liberties allowed them, and that divorce, unfaithfulness, wanton extravagance, and many other like evils were direfully common. Also the women were invading the arts and recreations of men — a proceeding the present age will view more leniently than did Juvenal.”

On women in general, the satirist Juvenal (c.55-c.130 A.D.) wrote in Satire 6 exc L: “Eppia, though the wife of a senator, went off with a gladiator to Pharos and the Nile on the notorious walls of Alexandria (though even Egypt condemns Rome's disgusting morals). Forgetting her home, her husband, and her sister, she showed no concern whatever for her homeland (she was shameless) and her children in tears, and (you'll be dumbfounded by this) she left the theatre and Paris the actor behind. Even though when she was a baby she was pillowed in great luxury, in the down of her father's mansion, in a cradle of the finest workmanship, she didn't worry about the dangers of sea travel (she had long since stopped worrying about her reputation, the loss of which among rich ladies' soft cushions does not matter much). Therefore with heart undaunted she braved the waves of the Adriatic and the wide-resounding Ionian Sea (to get to Egypt she had to change seas frequently). [Source: Diotma, Women’s Life in Greece & Rome by Mary R. Lefkowitze and Maureen B. Fant]

Cleopatra, much despised by Romans, and Caesar

“You see, if there's a good reason for undertaking a dangerous voyage, then women are fearful; their cowardly breasts are chilled with icy dread; they cannot stand on their trembling feet. But they show courageous spirit in affairs they're determined to enter illicitly. If it's their husband who wants them to go, then it's a problem to get on board ship. They can't stand the bilge-water; the skies spin around them. The woman who goes off with her lover of course has no qualms. She eats dinner with the sailors, walks the quarter-deck, and enjoys hauling rough ropes. Meanwhile the first woman gets sick all over her husband.

“And yet what was the glamour that set her on fire, what was the prime manhood that captured Eppia's heart? What was it she saw in him, that would compensate for her being called Gladiatrix? Note that her lover, dear Sergius, had now started shaving his neck, and was hoping to be released from duty because of a bad wound on his arm. Moreover, his face was deformed in a number of ways: he had a mark where his helmet rubbed him, and a big wart between his nostrils, and a smelly discharge always dripping from his eye. But he was a gladiator. That made him look as beautiful as Apollo's friend Hyacinth. This is what she preferred to her children and her homeland, her sister and her husband. It's the sword they're in love with: this same Sergius, once released from service, would begin to seem like her husband Veiento.

“Do you care about a private citizen's house, about Eppia's doings? Turn your eyes to the gods' rivals. Hear what the Emperor Claudius had to put up with. As soon as his wife thought that he was asleep, this imperial whore put on the hood she wore at night, determined to prefer a cheap pad to the royal bed, and left the house with one female slave only. No, hiding her black hair in a yellow wig she entered the brothel, warm with its old patchwork quilts and her empty cell, her very own. Then she took her stand, naked, her nipples gilded, assuming the name of Lycisca, and displayed the stomach you came from, noble Brittanicus. She obligingly received customers and asked for her money, and lay there through the night taking in the thrusts of all comers. Then when the pimp sent the girls home, at last she went away sadly, and (it was all she could do) was the last to close up her cell-she was still burning, her vagina stiff and erected; tired by men, but not yet satisfied, she left, her face dirty and bruised, grimy with lamp smoke, she brought back to her pillow the smell of the brothel.

“Isn't there anyone then in such large herds of women that's worth marrying? Let her be beautiful, graceful, rich, fertile, let her place on her porticoes her ancestors' statues; let her be more virginal than the Sabine women (the ones that with their dishevelled hair brought the war with Rome to an end); let her be a phoenix on earth, something like a black swan-but who could stand a wife who has every virtue? I'd rather have (much rather) a gal from Venusia than you, Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, if along with your great excellence you bring a snob's brow and count your family's triumphs as part of your dowry.

“All chance of domestic harmony is lost while your wife's mother is living. She gets her to rejoice in despoiling her husband, stripping him naked. She gets her to write back politely and with sophistication when her seducer sends letters. She tricks your spies or bribes them. Then when your daughter is feeling perfectly well she calls in the doctor Archigenes and says that the blankets are too heavy. Meanwhile, her lover, in hiding shut off from her, impatient at the delay, waits in silence and stretches his foreskin. Maybe you think that her mother will teach her virtuous ways-ones different from her own? It's much more productive for a dirty old lady to bring up a dirty little girl.

“There's hardly a case in court where the litigation wasn't begun by a female. If Manilia can't be defendant, she'll be the plaintiff. They'll draw up indictments without assistance, and are ready to tell Celsus the lawyer how to begin his speech and what arguments he should use.

“Who doesn't know about the Tyrian wrappers and the ointment for women's athletics? Who hasn't seen the wounds in the dummy, which she drills with continual stabbings and hits with her shield and works through the whole course of exercise-a matron, the sort you'd expect to blow the trumpet at the Floralia -unless in her heart she is plotting something deeper still, and seriously training for the actual games? How can a woman who wears a helmet be chaste? She's denying her sex, and likes a man's strength. But she wouldn't want to turn into a man, since we men get so little pleasure.

“Yet what a show there would be, if there were an auction of your wife's stuff-her belt and gauntlets and helmet and half-armour for her left leg. Or she can try the other style of battle-lucky you, when she sells her greaves. Yet these same girls sweat even in muslin, even the thinnest little netting burns their delicacies. Look at the noise she makes when she drives home the blows her trainer showed her, at the weight of her helmet, how solidly she sits on her haunches (like the binding around a thick tree), and laugh when she puts her armour aside to pick up her chamber-pot.

“You ask where these monsters come from, the source that they spring from? Poverty made Latin women chaste in the old days, hard work and a short time to sleep and hands calloused and hardened with wool-working, and Hannibal close to the city, [7] and their husbands standing guard at the Colline Gate-that kept their humble homes from being corrupted by vice. But now we are suffering from the evils of a long peace. Luxury, more ruthless than war, broods over Rome and takes revenge for the world she has conquered. No cause for guilt or deed of lust is missing, now that Roman poverty has vanished. Money, nurse of promiscuity, first brought in foreigners' ways, and effete riches weakened the sinews of succeeding generations. What does Venus care when she's drunk? She can't tell head from tail when she eats big oysters at midnight, and when her perfume foams with undiluted wine, when she drinks her conch-shell cup dry, and when in her dizziness the roof turns round and the table rises up to meet two sets of lights.

“An even worse pain is the female who, as soon as she sits down to dinner, praises Vergil and excuses Dido's suicide: matches and compares poets, weighing Vergil on one side of the scale and Homer in the other. Schoolmasters yield; professors are vanquished; everyone in the party is silenced. No one can speak, not a lawyer, not an auctioneer, not even another woman. Such an avalanche of words falls, that you'd say it's like pans and bells being beaten. Now no one needs trumpets or bronzes: this woman by herself can come help the Moon when she's suffering from an eclipse. As a philosopher she sets definitions on moral behaviour. Since she wants to seem so learned and eloquent she ought to shorten her tunic up to her knees and bring a pig to Sylvanus and go to the penny bath with the philosophers. Don't let the woman who shares your marriage bed adhere to a set style of speaking or hurl in well-rounded sentences the enthymeme shorn of its premise. Don't let her know all the histories. Let there be something in books she does not understand. I hate the woman who is continually poring over and studying Palaemon's treatise, who never breaks the rules or principles of grammar, and who quotes verses I never heard of, ancient stuff that men ought not to worry about. Let her correct her girl-friend's verses she ought to allow her husband to commit a solecism.

“Pauper women endure the trials of childbirth and endure the burdens of nursing, when fortune demands it. But virtually no gilded bed is laid out for childbirth-so great is her skill, so easily can she produce drugs that make her sterile or induce her to kill human beings in her womb. You fool, enjoy it, and give her the potion to drink, whatever it's going to be, because, if she wants to get bloated and to trouble her womb with a live baby's kicking, you might end up being the father of an Ethiopian-soon a wrong-coloured heir will complete your accounts, a person whom it's bad luck to see first thing in the morning.

More Misogyny from Juvenal

Juvenal (c.55-c.130 A.D.) wrote in Satire VI (xi.199-304, 475-503): The Women of Rome:

“Now tell me — if you can not love a wife,

Made yours by every tie, and yours for life,

Why wed at all? Why waste the wine and cakes,

The queasy-stomach=d guest, at parting, takes?

And the rich present, which the bridal right

Claims for the favors of the happy night,

The platter where triumphantly inscroll'd

The Dacian hero shines in current gold?

If you can love, and your besotted mind

Is so uxoriously to one inclined,

Then bow your neck, and with submissive air,

Receive the yoke you must forever wear.

[Source:William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 224-225, 239-244, 247-258]

“To a fond spouse, a wife no mercy shows

But warmed with equal fires, enjoys his woes.

She tells you where to love and where to hate,

Shuts out the ancient friend, whose beard your gate

Knew from its downy to its hoary state:

And when rogues and parasites of all degrees

Have power to will their fortune as they please,

She dictates yours, and impudently dares

To name your very rivals for your heirs.

“"Go crucify that slave." "For what offence?

Who=s the accuser? Where=s the evidence?

Hear all! no time, whatever time we take

To sift the charges, when man's life's at stake,

Can e'er be long: hear all, then, I advise!" —

“"You sniveler! is a slave a man" She cries:

"He's innocent? - be it so, - tis my command,

My will: let that, sir, for a reason stand."

Thus the virago triumphs, thus she reigns

Anon she sickens of her first domains,

And seeks for new; — husband on husband takes,

Till of her bridal veil one rent she makes.

Again she tires, again for change she burns,

And to the bed she lately left returns,

While the fresh garlands and unfaded boughs,

Yet deck the portal of her wondering spouse.

Thus swells the list - "Eight husbands in five years"

“A rare inscription on their sepulchers!

While your wife's mother lives, expect no peace.

She teaches her with savage joy to fleece

A bankrupt spouse; kind creature! she befriends

The lover's hopes, and when her daughter sends

An answer to his prayer, the style inspects,

Softens the cruel, and the wrong corrects. . .

“Women support the bar, they love the law,

And raise litigious questions for a show,

They meet in private and prepare the bill

Draw up instructions with a lawyer's skill,

Suggest to Celsus where the merits lie,

And dictate points for statement or reply.

“Nay more, they fence, who has not marked their oil,

Their purple rugs, for this preposterous toil?

Equipped for fight, the lady seeks the list

And fiercely tilts at her antagonist,

A post! which with her buckles she provokes,

And bores and batters with repeated strokes,

Till all the fencer's art can do she shows,

And the glad master interrupts her blows.

“The house appears like Phalaris' court,

All bustle, gloom and tears.

The wretched Psecas, for the whip prepared,

With locks disheveled, and with shoulders bared,

Attempts her hair; fire flashes from her eyes,

And Awretch! why this curl so high? she cries.

Instant the lash, without remorse, is plied,

And the blood stains her bosom, back and side.

Another trembling on the left prepares

To open and arrange the straggling hairs

To ringlets trim; meanwhile the council meet,

And first the nurse, a personage discreet,

Gives her opinion; then the rest in course

As age or practice lend their judgment force,

So warm they grow, and so much pains they take,

You'd think her honor or her life at stake,

So high they build her head, such tiers on tiers,

With wary hands, they pile, that she appears

Andromache before; — and what behind?

A dwarf, a creature of a different kind!”

Powerful Women in Ancient Rome

Claudia Metrodora was a Roman-Greek priestess devoted to Aphrodite Livia. According to Live Science: Although it was incredibly rare for women in ancient Rome to be directly involved in politics, Claudia Metrodora is one such example of a rich, powerful and influential person in her community. A Greek woman with Roman citizenship, Metrodora held extraordinary power on the island of Chios, reaching the most important position on that island. "Metrodora held several political offices, including twice being appointed "stephanophoros," the highest magistracy on Chios, and "gymnasiarch" (meaning official) four times," Joanne Ball, who has her doctorate in archaeology from the University of Liverpool, said. [Source Live Science, October 23, 2021]

Metrodora was also president of an important religious festival on three separate occasions. "One inscription in particular describes her as 'being desirous of glory for the city ... a lover of her homeland and priestess of life of the divine empress Aphrodite Livia, by reason of her excellence and admirable behaviour,'" Anneka Rene, a researcher at University of Auckland, said. "Metrodora's life in Chios is most illuminating of the power and riches women could wield. Whilst often assumed that women held power mostly behind the throne, she instead takes centre stage in her own story."

Unlike some of ancient Rome's other influential women, Metrodora didn't marry into her power. "The most remarkable thing about Claudia Metrodora is how visible she was in public life in both Chios and Ephesus [an ancient Greek city in what is now Turkey], defying the supposed conventions limiting female behaviour in the Roman-Greek world," Ball said. "She demonstrates that women could operate in civic life within the Romano-Greek world, financing public works and holding office in her own right, rather than wielding power indirectly through her husband or son."

See Messalina and Agrippina Under : CLAUDIUS'S WIVES: THE NYMPHOMANIAC MESSALINA AND THE SCHEMER AGRIPPINA europe.factsanddetails.com ; NERO (A.D. 37-68): HIS LIFE, DEATH, MOTHER AND WIVES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

See Julia Mamaea under ELAGABALUS (ANCIENT ROME’S WORST EMPEROR): HEDONISM, OSTRICH-BRAIN PIES AND POWERFUL MOTHERS europe.factsanddetails.com

See Livia Drusilla under AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, FAMILY, SOURCES europe.factsanddetails.com

See Fulvia under MARC ANTONY: HIS LIFE, RELATIONS WITH CAESAR AND MILITARY CAMPAIGNS europe.factsanddetails.com

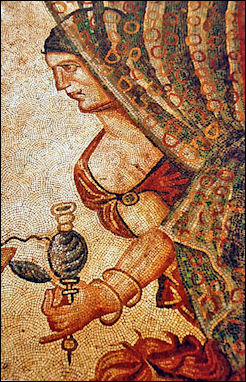

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024