Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire

NERO'S LIFE

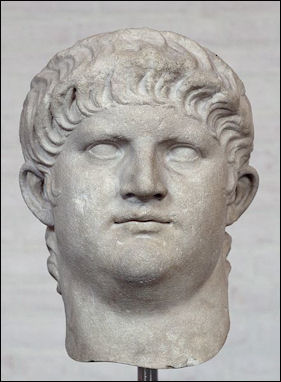

Nero (A.D. 37-68) was the fifth emperor of Rome, ruling from A.D. 54 to 68. He was named Roman emperor when he was seventeen, the youngest ever at that time. Nero's real name was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He is known mainly for being a cruel wacko but in many ways he left the Roman Empire better off than when arrived.

Nero (A.D. 37-68) was the fifth emperor of Rome, ruling from A.D. 54 to 68. He was named Roman emperor when he was seventeen, the youngest ever at that time. Nero's real name was Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He is known mainly for being a cruel wacko but in many ways he left the Roman Empire better off than when arrived.

Nero was the grandson of Germanicus and a descendant of Augustus. He was proclaimed Emperor by the praetorians (Roman army elite) and accepted by the senate. He had been educated by the great philosopher Seneca; and his interests had been looked after by Burrhus, the able captain of the praetorian guards. His accession was hailed with gladness. He assured the senate that he would not interfere with its powers. The first five years of his reign, which are known as the “Quinquennium Neronis,” were marked by a wise and beneficent administration.

During this time he yielded to the advice and influence of Seneca and Burrhus, some scholars believe practically controlled the affairs of the empire and restrained the young prince from exercising his power to the detriment of the state. Under their influence delation (accusing or bringing charges against someone, especially by an informer) was forbidden, taxes were reduced, and the authority of the senate was respected. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

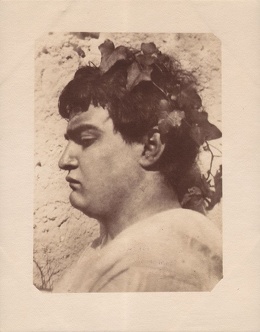

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “Nero was a grenade hurled into an already untidy social order. Despite blood connections with Augustus on both his maternal and paternal sides, he seemed anything but Roman: blond, blue-eyed, and freckle-faced, with an aptitude for art rather than war. Roberto Gervaso, the author of the 1978 biographical novel “Nerone” told National Geographic: “He was a monster. But that’s not all he was. And those who came before and after him were no better. The true monsters, like Hitler and Stalin, lacked [Nero’s] imagination. Even today he would be avant-garde, ahead of his time. [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

Contrary to the myth that Nero was a despised despot, J. Wisniewski wrote in Listverse: The Roman public adored Nero during and after his life. The emperor was so popular with the rest of the Roman public that many had themselves buried with portraits of Nero even long after he died. He was especially beloved compared to his successors. It didn’t hurt that during his lifetime, he led relief efforts during the Great Fire he didn’t start. The emperor also made it known that he vastly improved the food distribution system for the poor.After his untimely death in a coup, Nero developed an Elvis-like following. Across the empire, people sighted Nero, widely believing he had not died. They thought he was in exile, waiting for the right day to return and liberate Rome from boring, short-lived emperors like Otho and Galba. [Source J. Wisniewski, Listverse, July 21, 2014]

RELATED ARTICLES:

NERO (RULED A.D. 54-68) AS EMPEROR: EARLY PROMISE, REFORMS, LATER REVOLTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

GREAT FIRE OF ROME IN A.D. 64: NERO, EVIDENCE, STORIES, RUMORS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO'S GOLDEN HOUSE AND THE REBUILDING ROME AFTER THE GREAT FIRE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO'S CRUELTY — TOWARDS HIS FAMILY, AIDES AND CHRISTIANS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NERO’S BUFFOONERY, EXTRAVAGANCE AND STRANGE SEX LIFE factsanddetails.com

Book: “Nero” by Edward Champlin (Harvard University Press, 2003). Champlin is a professor of classics at Princeton. There is a splendid translation by Robert Graves of the biography of Nero by Suetonius.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Twelve Caesars” (Penguin Classics) by Suetonius (121 AD) Amazon.com

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine” by Barry S. Strauss (2019) Amazon.com

“The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C. - A.D. 476" by Michael Grant (1997) Amazon.com;

“Annals” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“Histories” by Tacitus (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com

“69 A.D.: The Year of Four Emperors” by Gwyn Morgan Amazon.com;

“Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern” by Mary Beard (2021) Amazon.com

“Pax: War and Peace in Rome's Golden Age” by Tom Holland (2023) Amazon.com

“Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World”

by Adrian Goldsworthy Amazon.com;

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Nero’s Family

Nero was born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus on December 15, A.D. 37 in Antium (modern Anzio), eight months after the death of the Roman Emperor Tiberius. He was an only-child. His father was Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and his mother was Agrippina the Younger (great-granddaughter of the emperor Augustus). Nero was three when his father died. By the time Nero turned eleven, his mother married Emperor Claudius, who then adopted Nero as his heir. [Source Wikipedia]

Nero was the grandson of the famed general Germanicus as well as a descendant of Augustus. Some have blamed Nero despicable behavior on his childhood. After his father died he was brought up in the home of his deranged uncle Caligula and raised by his "impetuous and deranged mother"Agrippina the Younger, who used "incest and murder" to secure him the throne over the rightful heir and eliminated rivals in her son's path to the emperorship by poisoning their food, it is said, with a toxin extracted from a shell-less mollusk known as a sea hare. See Caligula)

On Nero’s father, Suetonius wrote: “Domitius, who became the father of Nero,” was “a man hateful in every walk of life; for when he had gone to the East on the staff of the young Gaius Caesar [Caligula], he slew one of his own freedmen for refusing to drink as much as he was ordered, and when he was in consequence dismissed from the number of Gaius' friends, he lived not a whit less lawlessly. On the contrary, in a village on the Appian Way, suddenly whipping up his team, he purposely ran over and killed a boy, and right in the Roman Forum he gouged out the eye of a Roman eques for being too outspoken in chiding him. He was, moreover, so dishonest that he not only cheated some bankers of the prices of wares which he had bought, but in his praetorship he even defrauded the victors in the chariot races of the amount of their prizes. When for this reason he was held up to scorn by the jests of his own sister, and the managers of the troupes made complaint, he issued an edict that the prizes should thereafter be paid on the spot. Just before the death of Tiberius he was also charged with treason, as well as with acts of adultery and with incest with his sister Lepida, but escaped owing to the change of emperors, and died of dropsy at Pyrgi, after acknowledging Nero son of Agrippina, the daughter of Germanicus.”

Nero’s Mother Agrippina

Agrippina the Elder with the ashes of Germanicus; they were Agrippina the Younger's parents

Julia Agrippina (A.D. 15– 59), also referred to as Agrippina the Younger, was Roman empress from A.D. 49 to 54, the fourth wife and niece of emperor Claudius, and the mother of Nero. Isabel Barceló wrote in National Geographic History, Nobody could question Agrippina’s imperial credentials: great granddaughter of Augustus, great-niece of Tiberius (granddaughter of Drusus), sister to Caligula, wife of Claudius, and mother to Nero. Like her male relatives, she enjoyed great influence. Honored with the title Augusta in A.D. 50, she wielded political power like a man—and paid the price for it. [Source Isabel Barceló, National Geographic History, March 18, 2021]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Nero's mother, Agrippina, seems to have manipulated the emperor Claudius into adopting her son, who became emperor after Claudius' death in A.D. 54; and for a while she was hailed as the empire's co-ruler, although eventually Nero had her killed. Many of the stories associated with imperial women may have been embellished or invented, MIT historian William Broadhead told Live Science, but "even discounting the more scandalous features of the stories, we can appreciate the importance of [their] position within the imperial household as a determining factor in who gained the throne." [Source Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, August 15, 2022]

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: Nero’s “sly and ambitious mother, Agrippina, was accused of plotting to kill her brother Caligula and later probably killed her third husband, Claudius, with poisonous mushrooms. Having already arranged for the stoic essayist Seneca to mentor her young son, Agrippina proclaimed Nero a worthy successor to the throne, and in A.D. 54, just shy of age 17, he assumed it. Anyone curious about the mother’s intentions could find the answer on coins from the era, depicting the teenage emperor’s face no larger than that of Agrippina.” [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

Agrippina’s Early Life

Isabel Barceló wrote in National Geographic History: Around A.D. 15, Agrippina was born in a military camp on the banks of the Rhine to an influential Roman power: Germanicus, nephew and adopted son of the emperor Tiberius and a candidate to succeed him, and Agrippina the Elder, Augustus’ favorite granddaughter.When Agrippina was just four years old, Germanicus died of poisoning in Syria, a crime that her mother always attributed to Tiberius. Agrippina the Elder claimed that the emperor Tiberius feared Germanicus’s popularity with the army, believing that military support would eventually allow Germanicus to usurp the emperor and take his place. [Source Isabel Barceló, National Geographic History, March 18, 2021]

Germanicus’s widow, the indomitable Agrippina the Elder, arrived in Rome with her husband’s ashes, in what became an open challenge to the emperor. With the greatest dignity, she took the urn containing the ashes and, accompanied by her children and a huge crowd of mourning citizens, she led a silent procession through the streets of Rome to the mausoleum of Augustus, where she deposited it. Tiberius was furious at his daughter-in-law’s defiance and never forgave her. A few years later, the emperor had her two eldest sons murdered and banished her to one of the Pontine Islands where she died. These horrors, observed by Agrippina the Younger, while still a child, scarred her deeply

The younger Agrippina apparently received a solid education, and there is no doubt of her intelligence, nor of her determination and strength. From an early age, she certainly understood the workings of the imperial court and how a woman could maneuver within it. Her great-grandmother Livia, grandmother Antonia, and her mother taught her the mechanisms and dangers of life at court. Agrippina, in her role as Augusta, founded a Roman colony near her birthplace in what is today western Germany. Her father, Germanicus, had been stationed at a military outpost along the Rhine when Agrippina was born there in A.D. 15.

Caligula became seriously ill and, when he regained his health, began a bloody purge to eliminate rivals, reminiscent of the worst violence of Tiberius. Agrippina, having allegedly conspired in a plot to overthrow her brother, was accused of immoral conduct and exiled to the Pontine Islands. A year later, Caligula’s assassination unleashed a new wave of chaos before Agrippina’s paternal uncle, Claudius, took over as emperor in January, A.D. 41. Rome’s new ruler reversed the sentence on his niece and allowed her to return to Rome.

That same month, Agrippina became a widow after Ahenobarbus died, but she quickly remarried. Claudius arranged a union with a wealthy, well-connected man, Crispus, who had served twice as consul. The marriage lasted until Crispus’ death in 47, which left Agrippina a very wealthy widow. Rumors spread that she had caused her husband’s demise after he named her his heir. A year later, Claudius was widowed and began looking for a new wife. Despite Agrippina being his biological niece, her imperial ancestry made her a strong marital candidate. She was beautiful, still young, and brought with her, her son, who, as Germanicus’s grandson, was, in the words of Tacitus, “thoroughly worthy of imperial rank.” Claudius hoped that in this way she “would not carry off the grandeur of the Caesars to some other house.” Agrippina eventually became Claudius’ fourth wife.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “Roman Empress Agrippina was a master strategist. She paid the price for it” National Geographic History by Isabel Barceló, March 18, 2021 nationalgeographic.com/history

Murders and Maneuvering by Agrippina to Help Nero Become Emperor

Isabel Barceló wrote in National Geographic History: Agrippina began to make waves when her brother Caligula became emperor in A.D. 37. At age 22, she gave birth to Nero. From the very beginning, Agrippina was resolute in one aim: to see her son become emperor. It was not unreasonable, given her elite family credentials, nor was it unusual: Roman matrons were expected to promote their children’s interests. In Agrippina’s case, she had a strong personal drive to get involved in politics. In a society that kept women out of government, it was unthinkable that she, by herself, could enter the arena. Through Nero, she had a chance to grasp power, but securing the imperial throne for him would be both difficult and dangerous. [Source Isabel Barceló, National Geographic History, March 18, 2021]

Shortly after Claudius became emperor, his third wife Messalina gave birth to their son Britannicus, who had the strongest position to become his heir. Messalina ruthlessly tried to eliminate potential rivals—including Agrippina and her son Nero—through gossip, exile, and even murder. Messalina would eventually be undone by her numerous intrigues and affairs. The Praetorian Guard would execute her after word spread of her involvement in a plot to overthrow Claudius and make Britannicus emperor. With her rival out of the way, Agrippina smartly maneuvered to become Claudius’s next wife, unseat Britannicus as heir, and secure succession for Nero.

To pave the way for her son, Nero to become Emperor, Agrippina had Claudius's son Britannicus married off to Octavia, Claudius's daughter. With the help of the famous poisoner Locusta, Agrippina then tried to get rid of Claudius by arranging for him to be served a stew filled with poisonous mushroom. According to Tacitus Claudius began gasping almost immediately after eating the stew and lost his ability to speak. He was taken to bed and suffered through the night. When it became clear the dossage was not large enough, another dose of poison was administered either in his food or possibly by an enema. Claudius was dead by the next day.

Britannicus was later killed while dining with Nero and the entire royal family. Killing only Britannicus was a difficult task because the food of each member of the royal family was tasted first by a servant. Locusta devised a powerful poison that was given to Britannicus in a glass of cold water that was delivered after he complained about his first drink being too hot. After drinking the poison he fell backwards gasping for air. Some members of the family ran from the dinner table in horror while Nero looked on coolly, explaining that Britannicus was only having a epileptic seizure and would soon recover.

Nero’s Early Life

Nero was educated by the great philosopher Seneca; and his interests had been looked after by Burrhus, the able captain of the praetorian (elite army) guards. Suetonius wrote: “Nero was born at Antium nine months after the death of Tiberius, on the eighteenth day before the Kalends of January [December 15, 37 A.D.], just as the sun rose, so that he was touched by its rays almost before he could be laid upon the grounds. Many people at once made many direful predictions from his horoscope, and a remark of his father Domitius was also regarded as an omen; for while receiving the congratulations of his friends, he said that "nothing that was not abominable and a public bane could be born of Agrippina and himself." Another manifest indication of Nero's future unhappiness occurred on the day of his purification; for when Gaius Caesar was asked by his sister to give the child whatever name he liked, he looked at his uncle Claudius, who later became emperor and adopted Nero, and said that he gave him his name. This he did, not seriously, but in jest, and Agrippina scorned the proposal, because at that time Claudius was one of the laughing-stocks of the court. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“At the age of three he lost his father, being left heir to a third of his estate; but even this he did not receive in full, since his fellow heir Gaius seized all the property. Then his mother was banished too, and he was brought up at the house of his aunt Lepida almost in actual want, under two tutors, a dancer and a barber. But when Claudius became emperor, Nero not only recovered his father's property, but was also enriched by an inheritance from his stepfather, Passienus Crispus. When his mother was recalled from banishment and reinstated, he became so prominent through her influence that it leaked out that Messalina, wife of Claudius, had sent emissaries to strangle him as he was taking his noonday nap, regarding him as a rival of Britannicus. An addition to this bit of gossip is, that the would-be assassins were frightened away by a snake which darted out from under his pillow. The only foundation for this tale was, that there was found in his bed near the pillow the slough of a serpent; but nevertheless at his mother's desire he had the skin enclosed in a golden bracelet, and wore it for a long time on his left arm. But when at last the memory of his mother grew hateful to him, he threw it away, and afterwards in the time of his extremity sought it again in vain.

“While he was still a young, half-grown boy, he took part in the game of Troy at a performance in the Circus with great self-possession and success. In the eleventh year of his age [50 A.D.] he was adopted by Claudius and consigned to the training of Annaeus Seneca, who was then already a senator. They say that on the following night Seneca dreamt that he was teaching Gaius Caesar, and Nero soon proved the dream prophetic by revealing the cruelty of his disposition at the earliest possible opportunity. For merely because his brother Britannicus had, after his adoption, greeted him as usual as Ahenobarbus, he tried to convince his father [Claudius] that Britannicus was a changeling. Also, when his aunt Lepida was accused, he publicly gave testimony against her to gratify his mother, who was using every effort to ruin Lepida. At his formal introduction into public life he announced a largess to the people and a gift of money to the soldiers, ordered a drill of the praetorians and headed them shield in hand; and thereafter returned thanks to his father in the Senate. In the latter's consulship he pleaded the cause of the people of Bononia before him in Latin, and of those of Rhodes and Ilium in Greek. His first appearance as judge was when he was prefect of the city during the Latin festival, when the most celebrated pleaders vied with one another in bringing before him, not trifling and brief cases according to the usual custom, but many of the highest importance, though this had been forbidden by Claudius. Shortly afterwards he took Octavia to wife and gave games and a beast-baiting in the Circus, that health might be vouchsafed Claudius.

Nero’s Appearance, Health and Interests

Suetonius wrote: “He was about the average height, his body marked with spots and malodorous, his hair light blond, his features regular rather than attractive, his eyes blue and somewhat weak, his neck over thick, his belly prominent, and his legs very slender. His health was good, for though indulging in every kind of riotous excess, he was ill but three times in all during the fourteen years of his reign, and even then not enough to give up wine or any of his usual habits. He was utterly shameless in the care of his person and in his dress, always having his hair arranged in tiers of curls, and during the trip to Greece also letting it grow long and hang down behind; and he often appeared in public in a dining-robe [the "synthesina" was a loose robe of bright-colored silk, worn at dinner, during the Saturnalia, and by women at other times. Nero's is described by Dio, 63.13, as "a short, flowered tunic with a muslin collar."], with a handkerchief bound about his neck, ungirt and unshod [probably meaning "in slippers"]. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“When a boy, he took up almost all the liberal arts; but his mother turned him from philosophy, warning him that it was a drawback to one who was going to rule, while Seneca kept him from reading the early orators, to make his admiration for his teacher endure the longer. Turning therefore to poetry, he wrote verses with eagerness and without labor, and did not, as some think, publish the work of others as his own. I have had in my possession note-books and papers with some well-known verses of his, written with his own hand and in such wise that it was perfectly evident that they were not copied or taken down from dictation, but worked out exactly as one writes when thinking and creating; so many instances were there of words erased or struck through and written above the lines. He likewise had no slight interest in painting and sculpture.

“But above all he was carried away by a craze for popularity and he was jealous of all who in any way stirred the feeling of the mob. It was the general belief that after his victories on the stage he would at the next lustrum have competed with the athletes at Olympia; for he practiced wrestling constantly, and all over Greece he had always viewed the gymnastic contests after the fashion of the judges, sitting on the ground in the stadium; and if any pairs of contestants withdrew too far from their positions, he would force them forward with his own hand. Since he was acclaimed as the equal of Apollo in music and of the Sun in driving a chariot, he had planned to emulate the exploits of Hercules as well; and they say that a lion had been specially trained for him to kill naked in the arena of the amphitheatre before all the people, with a club or by the clasp of his arms.

Towards the end of his life, in fact, he had publicly vowed that if he retained his power, he would at the games in celebration of his victory give a performance on the water-organ, the flute, and the bagpipes and that on the last day he would appear as an actor and dance "Vergil's Turnus." Some even assert that he put the actor Paris to death as a dangerous rival. “He had a longing for immortality and undying fame, though it was ill-regulated. With this in view he took their former appellations from many things and numerous places and gave them new ones from his own name. He also called the month of April Neroneus and was minded to name Rome Neropolis.

“He utterly despised all cults, with the sole exception of that of the Syrian Goddess [Atargatis, the principal deity of Northern Syria, identified with Magna Mater and Caelestis; often mentioned in inscriptions and called by Apul. Metam. 8.25, omnipotens et omniparens], and even acquired such a contempt for her that he made water on her image, after he was enamored of another, superstition, which was the only one to which he constantly clung. For he had received as a gift from some unknown man of the commons, as a protection against plots, a little image of a girl; and since a conspiracy at once came to light, he continued to venerate it as a powerful divinity and to offer three sacrifices to it every day, encouraging the belief that through its communication he had knowledge of the future. A few months before his death he did attend an inspection of victims, but could not get a favorable omen.”

Nero’s Wives and Loves

Soon after he became Emperor, Nero married his first wife Octavia, the daughter of the Emperor Claudius, and stepsister of Nero. She was the only daughter of the Claudius’s marriage to his third wife, Valeria Messalina. She was named for her great-grandmother Octavia the Younger, the second eldest and full-blooded sister of the Emperor Augustus. Her elder half-sister was Claudia Antonia, Claudius's daughter through his second marriage to Aelia Paetina, and her younger brother was Britannicus, Claudius's son by Messalina. [Source: Wikipedia]

Joshua Levine wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Nero’s problems with his mother started early on, when he fell in love for real. Not with Octavia, his wife, alas. Nero’s arranged marriage to her brought neither love nor children. Instead, Nero fell hard for a lowborn freedwoman named Acte. He even flirted with the idea of marrying her, a project John Drinkwater, an emeritus professor of Roman history at the University of Nottingham, calls “absolutely silly.” But it is Agrippina’s disapproval of her son’s comportment — not just with his mistress but a new gang of friends his own age — that plants the wedge between them. He’s coming into his own and his mother is no longer the partner she intended to be. She’s an impediment. [Source: Joshua Levine; Smithsonian magazine, October 2020]

But ultimately the fate of Nero's wives was not very good. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: After Octavia was brutally murdered Nero allegedly kicked his pregnant second wife Poppaea to death in a fit of rage; and is said to have married a boy named Sporus. The likely enslaved Sporus apparently resembled Poppaea, whom Nero regretted killing. According to Suetonius, Nero had him castrated and married him in a traditional wedding ceremony complete with a veil and dowry. After that, Sporus appeared in public in the regalia of an empress and was allegedly addressed as “empress,” “lady,” or even “Poppaea.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 24, 2022]

Suetonius wrote: “Besides Octavia he later took two wives, Poppaea Sabina, daughter of an ex-quaestor and previously married to a Roman eques, and then Statilia Messalina, daughter of the great-grand- daughter of Taurus, who had been twice consul and awarded a triumph. To possess the latter he slew her husband Atticus Vestinus while he held the office of consul. He soon grew tired of living with Octavia, and when his friends took him to task, replied that "she ought to be content with the insignia of wifehood." Presently, after several vain attempts to strangle her, he divorced her on the ground of barrenness, and when the people took it ill and openly reproached him, he banished her besides; and finally he had her put to death on a charge of adultery that was so shameless and unfounded, that when all who were put to the torture maintained her innocence, he bribed his former preceptor Anicetus to make a pretended confession that he had violated her chastity by a stratagem. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Nero and Poppaea Sabina<br/> “He dearly loved Poppaea, whom he married twelve days after his divorce from Octavia, yet he caused her death too, by kicking her when she was pregnant and ill, because she had scolded him for coming home late from the races. By her he had a daughter, Claudia Augusta, but lost her when she was still an infant. Indeed, there is no kind of relationship that he did not violate in his career of crime. He put to death Antonia, daughter of Claudius, for refusing to marry him after Poppaea's death, charging her with an attempt at revolution; and he treated in the same way all others who were in any way connected with him by blood or by marriage. Among these was the young Aulus Plautius, whom he forcibly defiled before his death, saying "Let my mother come now and kiss my successor," openly charging that Agrippina had loved Plautius and that this had roused him to hopes of the throne. Rufrius Crispinus, a mere boy, his stepson and the child of Poppaea, he ordered to be drowned by the child's own slaves while he was fishing, because it was said that he used to play at being a general and an emperor. He banished his nurse's son Tuscus, because when procurator in Egypt he had bathed in some baths which were built for a visit of Nero. He drove his tutor Seneca to suicide, although when the old man often pleaded to be allowed to retire and offered to give up his estates, he had sworn most solemnly that he did wrong to suspect him and that he would rather die than harm him. He sent poison to Burrus, prefect of the Guard, in place of a throat medicine which he had promised him. The old and wealthy freedmen who had helped him first to his adoption and later to the throne, and aided him by their advice, he killed by poison, administered partly in their food and partly in their drink.”

Nero's Death

Nero killed himself on 8 June, 68 A.D. at the age of 30 a few miles outside of the city of Rome by falling on his sword. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: After a revolt, Nero fled Rome and was declared a public enemy of the state. Fearing the wrath of the Senate and concerned that a gruesome end awaited him, Nero had his secretary help him commit suicide. It turns out committed suicide unnecessarily to avoid what he thought was a public execution at the hands of the Roman Senate (they were actually trying to work out a compromise). [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 21, 2021]

Suetonius wrote: “The bitter feeling against him was increased because he also turned the high cost of grain to his profit [by using for his own purposes ships which would otherwise have been loaded with grain; but the text and the meaning are uncertain]; for indeed, it so fell out that while the people were suffering from hunger it was reported that a ship had arrived from Alexandria, bringing sand for the court wrestlers. When he had thus aroused the hatred of all, there was no form of insult to which he was not subjected. A curl [doubtless an allusion to the long hair which he wore during his Greek trip] was placed on the head of his statue with the inscription in Greek: "Now there is a real contest [in contrast with those of the stage], and you must at last surrender." To the neck of another statue a sack was tied and with it the words: "I have done what I could, but you have earned the sack" [the one in which parricides were put; see Aug. xxxiii.1]. People wrote on the columns that he had stirred up even the Gauls [there is obviously a pun on "Galli" (or "Gauls") and "galli" (or "cocks"), and on "cantare" in the sense of "sing" and of "crow"] by his singing. When night came on, many men pretended to be wrangling with their slaves and kept calling out for a defender [punning, of course, on Vindex, the leader of the revolt]. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

Nero's triumphant entrance to Rome

“In addition, he was frightened by manifest portents from dreams, auspices and omens, both old and new. Although he had never before been in the habit of dreaming, after he had killed his mother it seemed to him that he was steering a ship in his sleep and that the helm was wrenched from his hands; that he was dragged by his wife Octavia into thickest darkness, and that he was now covered with a swarm of winged ants, and now was surrounded by the statues of the nations which had been dedicated in Pompeius Magnus' theater and stopped in his tracks. An Hispanic steed of which he was very fond was changed into the form of an ape in the hinder parts of its body, and its head, which alone remained unaltered, gave forth tuneful neighs. The doors of the Mausoleum flew open of their own accord, and a voice was heard from within summoning him by name. After the Lares had been adorned on the Kalends of January, they fell to the ground in the midst of the preparations for the sacrifice. As he was taking the auspices, Sporus made him a present of a ring with a stone on which was engraved the rape of Proserpina. When the vows were to be taken [on the first of January, for the prosperity of the emperor and the state] and a great throng of all classes had assembled, the keys of the Capitol could not be found for a long time. When a speech of his in which he assailed Vindex was being read in the Senate, at the words "the wretches will suffer punishment and will shortly meet the end which they deserve," all who were present cried out with one voice: "You will do it, Augustus" [of course, used in a double sense]. It also had not failed of notice that the last piece which he sang in public was "Oedipus in Exile," and that he ended with the line: "Wife, father, mother drive me to my death."

“When meanwhile word came that the other armies had revolted, he tore to pieces the dispatches which were handed to him as he was dining, tipped over the table, and dashed to the ground two favorite drinking cups, which he called "Homeric," because they were carved with scenes from Homer's poems [Pliny, Nat. Hist. 37.29 tells us that the cups were of crystal]. Then taking some poison from Locusta and putting it into a golden box, he crossed over into the Servilian gardens, where he tried to induce the tribunes and centurions of the Guard to accompany him in his flight, first sending his most trustworthy freedmen to Ostia, to get a fleet ready. But when some gave evasive answers and some openly refused, one even cried: "Is it so dreadful a thing then to die?" [Verg. Aen. 12.646] Whereupon he turned over various plans in his mind, whether to go as a suppliant to the Parthians or Galba, or to appear to the people on the Rostra, dressed in black, and beg as pathetically as he could for pardon for his past offences; and if he could not soften their hearts, to entreat them at least to allow him the prefecture of Egypt. Afterwards, a speech composed for this purpose was found in his writing desk; but it is thought that he did not dare to deliver it for fear of being torn to pieces before he could reach the Forum. Having therefore put off further consideration to the following day, he awoke about midnight, and finding that the guard of soldiers had left, he sprang from his bed and sent for all his friends. Since no reply came back from anyone, he went himself to their rooms a with a few followers. But finding that the doors were closed and that no one replied to him, he returned to his own chamber, from which now the very caretakers had fled, taking with them even the bed-clothing and the box of poison. Then he at once called for the gladiator Spiculus or any other adept at whose hand he might find death, and when no one appeared, he cried "Have I then neither friend nor foe?" and ran out as if to throw himself into the Tiber.

Remorse of Nero after the Murder of his Mother

“Changing his purpose again, he sought for some retired place, where he could hide and collect his thoughts; and when his freedmen Phaon offered his villa in the suburbs between the Via Nomentana and the Via Salaria near the fourth milestone, just as he was, barefooted and in his tunic, he put on a faded cloak, covered his head, and holding a handkerchief before his face, mounted a horse with only four attendants, one of whom was Sporus. At once he was startled by a shock of earthquake and a flash of lightning full in his face, and he heard the shouts of the soldiers from the camp hard by, as they prophesied destruction for him and success for Galba. He also heard one of the wayfarers whom he met say: "These men are after Nero," and another ask: "Is there anything new in the city about Nero?" Then his horse took fright at the smell of a corpse which had been thrown out into the road, his face was exposed, and a retired soldier of the Guard recognized him and saluted him. When they came to a by-path leading to the villa, they turned the horses loose and he made his way amid bushes and brambles and along a path through a thicket of reeds to the back wall of the house, with great difficulty and only when a robe was thrown down for him to walk on. Here the aforesaid Phaon urged him to hide for a time in a pit, from which sand had been dug, but he declared that he would not go under ground while still alive, and after waiting for a while until a secret entrance into the villa could be made, he scooped up in his hand some water to drink from a pool close by, saying: "This is Nero's distilled water" [referring to a drink of his own contrivance, distilled water cooled in snow; cf., Pliny, Nat. Hist. 31.40]. Then, as his cloak had been torn by the thorns, he pulled out the twigs which had pierced it, and crawling on all fours through a narrow passage that had been dug, he entered the villa and lay down in the first room ["Cella" implies a small room, for the use of slaves] he came to, on a couch with a common mattress, over which an old cloak had been thrown. Though suffering from hunger and renewed thirst, he refused some coarse bread which was offered him, but drank a little lukewarm water.

Remorse of Nero after the Murder of his Mother

“At last, while his companions one and all urged him to save himself as soon as possible from the indignities that threatened him, he bade them dig a grave in his presence, proportioned to the size of his own person, collect any bits of marble that could be found, and at the same time bring water and wood for presently disposing of his body [the water was for washing his corpse and the fire for burning it]. As each of these things was done, he wept and said again and again: "What an artist the world is losing!" While he hesitated, a letter was brought to Phaon by one of his couriers. Nero snatching it from his hand read that he had been pronounced a public enemy by the Senate, and that they were seeking him to punish him in the ancient fashion [Cf., Claud. xxxiv.1], and he asked what manner of punishment that was. When he learned that the criminal was stripped, fastened by the neck in a fork [two pieces of wood, fastened together in the form of a "V"], and then beaten to death with rods, in mortal terror he seized two daggers which he had brought with him, and then, after trying the point of each, put them up again, pleading that the fated hour had not yet come. Now he would beg Sporus to begin to lament and wail, and now entreat someone to help him take his life by setting him the example; anon he reproached himself for his cowardice in such words as these: "To live is a scandal and shame — this does not become Nero, does not become him —one should be resolute at such times — come, rouse oneself!" And now the horsemen were at hand who had orders to take him off alive. When he heard them, he quavered: "Hark, now strikes on my ear the trampling of swift-footed coursers!" [Iliad 10.535], and drove a dagger into his throat, aided by Epaphroditus, his private secretary [See Domitian xiv.4]. He was all but dead when a centurion rushed in, and as he placed a cloak to the wound, pretending that he had come to aid him, Nero merely gasped: "Too late!" and "This is fidelity!" With these words he was gone, with eyes so set and starting from their sockets that all who saw him shuddered with horror. First and beyond all else he had forced from his companions a promise to let no one have his head, but to contrive in some way that he be buried unmutilated. And this was granted by Icelus, Galbas' freedman [See Galba xiv.2], who had shortly before been released from the bondage to which he was consigned at the beginning of the revolt.

After Nero's Death

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Suetonius claimed that everyone in Rome delighted in the news of his suicide, but Tacitus notes that lower status inhabitants were upset. According to Philostratus, those in the Eastern provinces mourned Nero. Like others, Nero was the victim of a damnatio memoriae, a process in which the memory of a person (usually an emperor but sometimes also other important people) was erased through the defacing of monuments and coins. The problem with this process, as Princeton classicist Harriet Flower has written, is that it just doesn’t work. Excisions leave a mark that only draws more attention to what was once there. Erasure was especially ineffective in the case of Nero: The man who could not be controlled in life could not be controlled in death either.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 24, 2022]

Even though Nero was dead, legends about his return persisted for centuries. At least three imposters emerged during the reigns of his successors. Each pretender gained followers, was captured, and killed but the Nero Redivus legend continued to gain traction with his supporters.

As Shushma Malik, an Assistant Professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge told me: “He had a public funeral and was buried in his family’s mausoleum on the Pincian Hill.” That should have been that, said Malik, “but there’s a twist.” In the years following his death, “two or perhaps three separate imposters appeared in the east claiming to be Nero — the rightful emperor who had not died as people thought, but had instead fled from Rome. Using his name, the imposters collected supporters with a view to reclaiming the Roman ‘throne’. On all occasions, these false Neros were unsuccessful.” But their facility in music and vague similarity to Nero rallied people to their cause and stoked the fires of a tradition that Nero would one day return.

One of the reasons for the emergence of these rumors, said Malik, is that Nero’s death had triggered a civil war also known as the Year of the Four Emperors ( A.D. 69). During this turbulent period Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian all vied for imperial power, but Vespasian emerged victorious and founded the Flavian dynasty. It seems, says Malik, that in the Eastern provinces, where people didn’t hear rumors about matricide and forcible castration, Nero was sincerely mourned. This wistfulness, Nero’s youth, and the private nature of his death created a space for rumors to flourish. She pointed to Dio Chrysostom, a first-century Greek-speaking Turk, who wrote “Indeed the truth about [Nero] has not come out even yet; for so far as the rest of his subjects were concerned, there was nothing to prevent his continuing to be Emperor for all time, seeing that even now everybody wishes he were still alive.” (Orations 21.9-10).

Suetonius wrote: “He met his death in the thirty-second year of his age, on the anniversary of the murder of Octavia, and such was the public rejoicing that the people put on liberty-caps and ran about all over the city. Yet there were some who for a long time decorated his tomb with spring and summer flowers, and now produced his statues on the Rostra in the fringed toga, and now his edicts, as if he were still alive and would shortly return and deal destruction to his enemies. Nay more, Vologaesus, King of the Parthians, when he sent envoys to the Senate to renew his alliance, earnestly begged this too, that honor be paid to the memory of Nero. In fact, twenty years later, when I was a young man, a person of obscure origin appeared, who gave out that he was Nero, and the name was still in such favor with the Parthians, that they supported him vigorously and surrendered him with great reluctance. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

“He was buried at a cost of two hundred thousand sesterces and laid out in white robes embroidered with gold, which he had worn on the Kalends of January. His ashes were deposited by his nurses, Egloge and Alexandria, accompanied by his mistress Acte, in the family tomb of the Domitii on the summit of the Hill of Gardens [the modern Pincio], which is visible from the Campus Martius. In that monument his sarcophagus of porphyry, with an altar of Luna marble standing above it, is enclosed by a balustrade of Thasian stone.”

Nero’s Legacy

Nero's death was followed by the Year of the Four Emperors (A.D. 69), in which Rome was lead in succession by Galba, Otho, Vitellisu and Vespasian. After his death his Golden Palace was stripped of its ivory, jewels and marble. The emperor Vespasian built the Colosseum, over the artificial lake. And the Emperor Trajan covered much of the palace with the Baths of Trajan.

Federico Gurgone wrote in Archaeology magazine: Nero's death brought to a close the Julio-Claudian dynasty that had begun with Augustus, and ended a reign distinguished by excessive lasciviousness, cruelty, and violence, and that led to civil war. The next three emperors ruled for only 18 months in total, and all were either murdered or committed suicide. It was not until December of A.D. 69, when Vespasian became emperor, that a period of relative calm that was to last more than a decade began. [Source: Federico Gurgone, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

In spite of such enormous crimes as those practiced by Nero, the larger part of the empire was beyond the circle of his immediate influence, and remained undisturbed. While the palace and the city presented scenes of intrigue and bloodshed, the world in general was tranquil and even prosperous. Except the occasional extortion by which the princes sought to defray the expenses of their debaucheries, Italy and the provinces were reaping the fruits of the reforms of Julius Caesar and Augustus. During this early period, the empire was better than the emperor. Men tolerated the excesses and vices of the palace, on the ground that a bad ruler was better than anarchy. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: In her book, The Nero Anti-Christ Founding and Fashioning a Paradigm, Malik explores the long history of hopeful and condemnatory traditions about Nero. There were many who remembered him fondly. An oversized status from second-century Tralles (modern day Turkey), for example, demonstrated this well. It’s really two groups of people — second- and third-century Roman elites (like Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio) and early Christians — who despised him. From the third century on, shows Malik, Christians began to explicitly associate Nero with the beast of Revelation and the eschatological Antichrist. The widespread belief that Nero might return, especially as an eschatological monster, persisted for centuries. As late as A.D. 422, St. Augustine of Hippo was referring to it. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 24, 2022]

Nero’s Ghost

Lanta Davis and Vince Reighard wrote in National Geographic: Nero’s ghost was said to haunt medieval Rome. According to legend, a walnut tree near the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo became the epicenter of demonic activity, where demons were said to emerge and terrorize pilgrims. Beneath the tree, it was said, lay the skeleton of Nero. Pope Paschal II had the tree chopped down to rid Rome of his spirit and Nero’s bones cast into the Tiber River. [Source Lanta Davis and Vince Reighard, National Geographic, October 4, 2024]

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: “Nero's death was followed by outpourings of public grief so widespread that his successor Otho hastily renamed himself Otho Nero. Mourners long continued to bring flowers to his tomb, and the site was said to be haunted until, in 1099, a church was erected on top of his remains in the Piazza del Popolo. There were sightings of “false Neros” and the persistent belief that the boy king would one day return to the people who so loved him. [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, September 2014 ~]

In his book “Nero,” Edward Champlin, Champlain makes a case that Nero had “had an afterlife that was unique in antiquity." Like Alexander the Great or even Jesus Christ, he was widely seen in the popular imagination as “the man who has not died but will return, and the man who died but whose reputation is a powerful living force” and was thus — a man who was very much missed." The “evolution of a historical person into a folkloric hero says little about the actual person but much about what some people believe...The immortal hero of the folklore embodies a longing for the past and explanation of the present, and most powerfully, a justification for the future."

Hollywood, the Nobel Prize and Nero

Joshua Levine wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In Mervyn LeRoy’s 1951 epic Quo Vadis, the actor Peter Ustinov actor was nominated for an Oscar for his “deliciously hammy Nero” ). “Look what I have painted!” shrieks Ustinov as he watches the Technicolor flames engulf his city. Ustinov calls for his lyre. He commences to pluck. “I am one with the gods immortal. I am Nero the artist who creates with fire,” he sings tunelessly. “Burn on, O ancient Rome. Burn on!” A panicky mob converges on the palace. “They want to survive,” explains Nero’s levelheaded counselor Petronius (portrayed by Leo Genn, also nominated for an Oscar). “Who asked them to survive?” shrugs Nero. Great cinema it isn’t, but it is terrific stuff all the same. And this is more or less the consensus Nero of history, set down first by the Roman historians Tacitus and Suetonius and etched deeper by the New Testament Book of Revelation and later Christian writings. [Source: Joshua Levine; Smithsonian magazine, October 2020]

“The man most responsible for Nero’s modern incarnation is the Polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, whose Quo Vadis: A Narrative of the Time of Nero, appeared in 1895 and was the basis for the Mervyn LeRoy film and half a dozen other cinematic versions. The plot centers on the doomed love between a young Christian woman and a Roman patrician, but their pallid romance is not what turned the novel into a worldwide sensation. Sienkiewicz researched Roman history deeply; his Nero and other historical characters hum with authenticity. It was they, more than the book’s fictional protagonists, who vaulted Quo Vadis to runaway best-seller status, translated into over 50 languages. Sienkiewicz ended up winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1905.

“Sienkiewicz plucks two strings that resonated loudly with his audience, and have done so ever since: Nero’s role as the emblematic persecutor of early Christianity (Poland is a deeply Catholic country) and Nero’s political tyranny (to Sienkiewicz, an ardent nationalist, Nero’s Rome stood in for czarist Russia).

Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker: In a more recent popular depiction, a TV movie directed by the late Paul Marcus, Nero is represented as a pretty-boy prince traumatized by having witnessed his father being murdered by the emperor Caligula; Nero starts his reign with good intentions before embarking upon his own program of Caligula-style excesses. His popular reputation even features in that comprehensive catalogue of humanity “The Simpsons,” in an episode in which Homer takes his evangelical neighbor, Ned Flanders, to Las Vegas for an experiment in depravity. After a night of boozing at the tables, they wake to find that each has married a cocktail waitress from the hotel casino where they are staying: Nero’s Palace. [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, June 7, 2021]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024