Home | Category: Famous Emperors in the Roman Empire

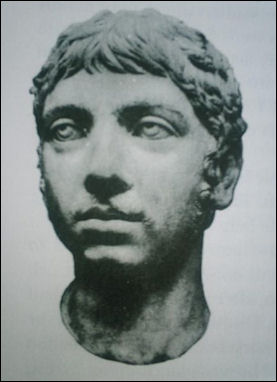

ELAGABALUS

Elagabulus In the early A.D. 3rd century, the imperial court was dominated by formidable women who arranged the succession of Elagabalus in A.D. 218. Under the youthful Elagabalus (ruled A.D. 218-222), regarded by some as the worst Roman Emperor, and Severus Alexander (ruled A.D. 222-235), the Roman Empire was for all intents and purposes run by their grandmother Julia Maesa and their mothers.

Elagabalus started dressing in drag shortly after he was named emperor. He enjoyed pretending he was a woman so much that he ordered the senate to address him as the "Empress of Rome." He once ordered 600 ostriches killed so his cooks could make him ostrich-brain pies. He made appointments by choosing men with the largest penises.

Notorious for sacrilegous acts and hedonism, the excesses of Elagabalus were way over the top, even in ancient Rome. As a teenage emperor Elagabalus hosted a famous feast which featured camels feet; honeyed dormice; the brains of 600 ostriches; conger eels fattened on Christian slaves; and caviar from fish caught with emperor's private fishing fleet. Guest were also given a dish with a sauce made by a chef who had to eat nothing but that sauce if the emperor didn't like it.

Elagabalus reportedly came to the banquet on a chariot pulled by naked women and is said to have liked to mix gold and pearls with peas and rice. He ate and drank from bejeweled gold plates and goblets. Guests to his banquets were given free slaves and homes and live versions of the animals they had just eaten. His idea of practical jokes was to play a game and give the winner a prize of dead flies and drug guests wine and have them wake in a room filled with lions and leopards. These excesses exhausted Rome's treasury and Elagabalus met his end, assassinated in a latrine.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Mad Emperor: Heliogabalus and the Decadence of Rome” by Harry Sidebottom (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor” by Martijn Icks (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Emperor Elagabalus” by Leonardo De Arrizabalaga Y Prado (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine” by Patricia Southern (2015) Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome” by Chris Scarre (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome 31 B.C. - A.D. 476" by Michael Grant (1997) Amazon.com;

“Emperor of Rome” by Mary Beard (2023) Amazon.com

“Emperor in the Roman World” by Fergus Millar (1977) Amazon.com

“The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1776), six volumes Amazon.com

“The Women of the Caesars” by Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942), translated by Frederick Gauss Amazon.com;

“First Ladies of Rome, The The Women Behind the Caesars” by Annelise Freisenbruch (2010) Amazon.com;

Life of Elagabalus

The man who became infamous as Elagabalus was born Varius Avitus Bassianus in Emesa, the city of Homs in Syria today. There he served as high priest of the sun god Elah-Gabal, a local form of the god Baal.

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: At age 14, Bassianus became emperor of Rome and assumed the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus in A.D. 218. From that moment, his short, chaotic reign would scandalize Rome. Lurid sexual encounters, extravagant stunts and parties, and, in a dramatic break with Roman tradition, forced worship of Elah-Gabal in spectacular public rituals marked his four years on the throne. An emblem of Roman decadence, an aura of fascination clings to this teenage emperor who, because of his association with the cult of Elah-Gabal, came to be known as Elagabalus. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez,National Geographic History, March 19, 2019]

The accounts of his life spill into the fantastical. But while the stories about him are, without doubt, exaggerated, they have continued to inspire art, literature,and drama down to the present day. Much of the information on Elagabalus is drawn from a collection of biographies of emperors known as the Augustan History. The section on the teenage emperor was supposedly written by one Aelius Lampridius. Modern historians not only cast a great deal of doubt on his account, but also consider that Aelius is an assumed name. Whoever the writer really was, his tone was decidedly sensationalist: “The life of Elagabalus Antoninus, also called Varius, I should never have put in writing—hoping that it might not be known that he was emperor of the Romans.”

Life of Elagabalus

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: What historians know with certainty is that, in spite of his birth in distant Syria, Elagabalus belonged to the highly influential Severan dynasty, which dominated Roman politics at the end of the second century and beginning of the third. Under the African emperor Septimius Severus and his wife, the Syrian Julia Domna, Rome enjoyed a long period of stability from 193 to 211. But this gave way to growing tensions during the reign of his successor Caracalla. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, March 19, 2019]

In 217 a soldier assassinated Caracalla, and a usurper, General Macrinus, took his place. Macrinus was a mere praetor, a judicial official, with little political experience. He turned out to be an incompetent general, too, leading his army to defeat against the Parthians, Rome’s great enemy in the Middle East. Macrinus’s popularity took another hit when he signed an ignominious peace treaty with Parthia, leading to more discontent among his eastern troops. But Macrinus’s biggest error was underestimating just how much Caracalla’s family wanted to return to power.

Julia Maesa, sister-in-law to Septimius Severus, had an unmatched talent for intrigue and political maneuvering. To put her family back on the throne, she conspired to have Macrinus overthrown. In his place, she suggested a new heir: her teenage grandson Bassianus. To strengthen his claim to the throne, Julia spread the rumor that he was Caracalla’s illegitimate son. Young Bassianus did bear a striking family resemblance to Caracalla, although he was, in fact, just a cousin. To further back her play, Julia bribed the Roman troops stationed in Syria to secure their support.

Around this time, Bassianus had inherited his family’s position as high priest and was worshipping the god Elah-Gabal in his home city in Syria. According to one account, he captured the attention of the Roman soldiers stationed there. Allegedly they would come to the temple to see him, both fascinated by and attracted to his good looks that he further enhanced by wearing costly jewelry and trinkets.

Backed by the military and false claims of parentage, Julia Maesa managed to get her way. Bassianus was presented to the centurion Publius Valerius Comazon and his troops. Fully convinced of his good Severan credentials, they proclaimed Bassianus the new emperor of Rome. The other eastern legions were quick to follow in recognizing him. A eunuch who served as Bassianus’s tutor, Gannys, would become a general, and would defeat Macrinus in Antioch, in modern-day Turkey, less than a month later. After the usurper’s capture and execution, Julia Maesa’s victory was secure.

How Elagabalus Became the Roman Emperor

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Despite the lure of imperial life in Rome, the new emperor made his own rules with no regard for Roman customs and culture. He refused to adopt the traditional gods of Rome and abandon his own. Instead, he stayed faithful to his cult of Elah-Gabal and brought a statue of the god with him on the nearly 2,000-mile journey from Syria to Rome. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, March 19, 2019]

Utterly unconcerned with doing what was politically appropriate or diplomatic, the new emperor, soon known as Elagabalus, built a temple to the Syrian deity on Palatine Hill. Despite being emperor, he continued in his role as high priest throughout his reign. Cows, sheep, and—according to the more sensational accounts—even humans, were sacrificed in honor of Elah-Gabal. Accounts say that the finest wines were mixed with sacrificial blood and poured out as offerings.

Elagabalus showed no respect to any religious cult other than his own. He even profaned the House of the Vestal Virgins in the Forum by taking one of the sacred virgins as his wife. “There is nothing more appropriate than the marriage of a priest to a priestess,” he told a stunned Senate. This act, probably more than any other, shocked Rome to the core.

The scandals and excesses of the emperor apparently knew no bounds. In one account he is said to have amazed the Roman people with his naumachiae, simulated naval battles held in the Circus Maximus, with ships floating on wine to evoke the “wine-dark sea” of Homer’s Odyssey. Just as impressive were the elaborate processions in which chariots pulled by elephants, tigers, and lions scaled the Vatican Hill, trampling any tomb that lay in their path.

At his banquets, and while presiding at games, the Augustan History relates, Elagabalus hugely enjoyed distributing presents or “chances” to the populace. One day it might be a fine piece of steak, another day a dead dog, or hundreds of gold coins, so that he could amuse himself watching the people scramble for them. The same source also relates how he might, on a whim, serve “food” made of wax, wood, stone, or marble. Once he is said to have rained down so many flower petals on his dinner guests that they almost suffocated.

Elagabalus’ Hedonism

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: Above all, Elagabalus had a reputation for giving free rein to his sexual impulses and took many lovers of both sexes. “He never had intercourse with the same woman twice except with his wife,” the Augustan History relates, “and he opened brothels in his house for his friends, his clients, and his slaves.” [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, March 19, 2019]

On one occasion he gathered all the city’s prostitutes in the Forum and appeared before them “in a woman’s costume and with protruding bosom.” He then proceeded to harangue the assembled crowd as if giving orders to ranks of soldiers. He instructed them in sexual practices and spurred them on, promising generous prizes if they complied with his bizarre demands.

The most coveted positions of state were held by the charioteers, athletes, and slaves whose job it was to satisfy Elagabalus’s carnal needs. The emperor had a particular fondness for Hierocles, a charioteer whom he called “husband.” Elagabalus kept many other lovers besides Hierocles, however, and would deliberately allow himself to be discovered with other favorites in the hope of being “punished” with a beating from Hierocles. (Read about chariot racing during the Roman Empire.)

Elagabalus opened up the imperial baths to the public so that he could enjoy watching the users bathe naked. He had his servants scour the streets and ports in search of men who seemed particularly virile. They came across Aurelius Zoticus, an athlete from Smyrna, who apparently fit the bill. Escorted by a large imperial guard, exceeding that provided even for visiting dignitaries, Zoticus arrived at the palace for his assignation with the emperor. But the charioteer Hierocles, fearing he was about to be usurped in Elagabalus’s affections, bribed the imperial cupbearers to administer a drug to Zoticus that robbed him of his legendary prowess. Elagabalus’s behavior outraged Rome, from the Praetorian Guard to the Senate to the common people.

Elagabalus’ Grandmother Takes Control

Juan Pablo Sánchez wrote in National Geographic History: A Syrian oracle had once warned Elagabalus that he should expect a short life and violent death. Preferring the idea of killing himself to that of being assassinated, the emperor stockpiled silver daggers and poison. He even had a very tall tower built and decorated with gold and diamonds so that should the critical moment arrive he could throw himself to his death. Elagabalus, who would wear nothing but Chinese silk next to his skin, was adamant in his wish to die in style. [Source Juan Pablo Sánchez, National Geographic History, March 19, 2019]

Despite such lavish preparations, his end was brutal and inglorious. Just as she had engineered the beginning of his career, Julia Maesa masterminded the end of Elagabalus’s controversial rule. She convinced him to adopt his 12-year-old cousin Alexander as successor, who rapidly became popular across Roman society. Alarmed, Elagabalus plotted to have him killed, but news of the assassination plot triggered a military revolution.

Elagabalus riding rather than leading the god's chariot, by Auguste Leroux, from the 1902 edition of Jean Lombard's L'agonie

Siding with the young Alexander, Julia looked on as her 18-year-old grandson was stabbed to death by his soldiers. Elagabalus’s body was tossed into the Tiber where it was carried by the waters from the Cloaca Maxima sewer, passing into history as the stereotype of the decadent Roman emperor.

Julia Mamaea, Elagabalus’s Aunt and Mother of His Successor

According to Live Science: Born in Syria, then part of the Roman Empire, Julia Mamaea was from a noble and powerful family, which included Emperor Caracalla (A.D. 188-217), her cousin. After Caracalla was assassinated in A.D. 217, Julia's nephew Elagabalus eventually took the throne, and Julia and her son Alexander Severus were brought into the heart of the imperial court. [Source Live Science, October 23, 2021

"Her son's time in court would lead him into favour with the Praetorian Guard, a unit who served as the emperor's bodyguard," Rene said. "Julia encouraged this support, reportedly distributing gold to them and encouraging them to keep her son safe from plots against him." Because she was a woman, Julia was not permitted to rule the empire, so she decided to pursue her ambitions through her son.

In A.D. 222, Elagabalus was assassinated, and the Praetorian Guard supported Severus as his successor, largely because of the political support that Mamaea had bought from the Praetorians, according to aid Joanne Ball, who has her doctorate in archaeology from the University of Liverpool. "Having bought her son's throne, Julia Mamaea became his Augusta, the highest rank a woman could be given," Ball said. "She was closely involved in the governance of the Empire — so much so that Alexander Severus became seen as an ineffective and weak emperor, impassive when compared to his mother, and a 'mama's boy.' Julia Mamaea dominated Imperial policy during her son's reign."

In A.D. 235, the army, frustrated by the emperor's lack of leadership, assassinated Mamaea and her son while she accompanied him on a campaign in Germania. In keeping a tight control over her son, Julia ultimately secured his downfall, as her influence meant that he could never develop into an effective leader in his own right, and in failing to secure the long-term support of the army, his long-term prospects would always be limited," Ball said. "Julia Mamaea knew that a Roman woman could only rule through her husband or son but forgot that her influence needed to be wielded as invisibly as possible. Her refusal, or inability, to step back would turn the Roman army against her son and led to his death and her own."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024