Home | Category: Age of Augustus

MARC ANTONY

Marc Antony coin

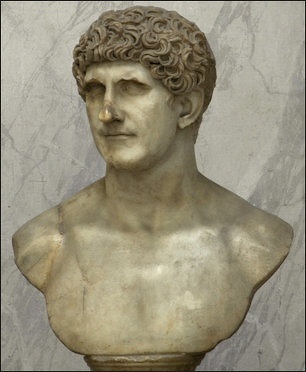

Marcus Antonius (83–30 B.C.), commonly known as Marc or Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of Rome from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire. Antony was a relative and supporter of Julius Caesar, and he served as one of his generals during the conquest of Gaul and Caesar's civil war. After Caesar’s death he first united with Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus) and then fought with him over who would be the sole leader over the fast-growing Roman Empire.

After Caesar's death Marc Antony and his ally Lepidus ultimately prevailed in their war with Cassius and Brutus for control of Rome and divided the Roman Empire among themselves, with Antony getting the East and Lepidus getting the West. In 41 B.C., while on tour of his empire to make alliances and secure funds for attack on the Parthians in Iran, Antony met Cleopatra.

At that time, Anthony was handsome and had thick curly hair. He claimed he was a descendent of Hercules and sometimes identified himself with Dionysus. Plutarch described Antony as mellow and generous but a bit of slob. Cicero called him a "a kind of butcher or prizefighter" and said his all-night orgies made him "odius." He also had a reputation for getting so drunk at all-male parties that he threw up into his own toga.

Even though women and soldiers loved him, Antony's biographer Adrian Goldsworthy dismisses him as a “not an especially good general” and wrote: “There is no real trace of any long-held beliefs or causes on Antony's part” beyond “glory and profit,"

Book: “Cleopatra and Antony” by Diana Preston, well-written and engaging rehashing of the story. “Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy (Yale, 2010) emphasizes the military side of their relationship.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AFTER THE ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

AUGUSTUS (RULED 27 B.C.-A.D. 14): HIS LIFE, FAMILY, SOURCES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CICERO'S MURDER, EVENTS AFTER CAESARS'S DEATH AND THE END OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA (69-30 B.C.): LOOKS, SEX LIFE, FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CLEOPATRA AND MARC ANTONY: ROMANCE, EVENTS, EXTRAVAGANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATTLE OF ACTIUM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND DEATHS OF ANTONY, CLEOPATRA AND THEIR CHILDREN europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mark Antony: A Life” by Patricia Southern (2012) Amazon.com;

“Mutina 43 BC: Mark Antony's Struggle for Survival” by Nic Fields, Peter Dennis (Illustrator) (2018) Amazon.com;

“Fulvia: Playing for Power at the End of the Roman Republic” by Celia E. Schultz Amazon.com;

“Social Science Series, Vol. III, No. 2. Antony's Oriental Policy until the Defeat of the Parthian Expedition” by Lucile Craven (1920) Amazon.com;

“A Noble Ruin: Mark Antony, Civil War, and the Collapse of the Roman Republic”

by W. Jeffrey Tatum Amazon.com

“The War That Made the Roman Empire: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium” by Barry S. Strauss (2022) Amazon.com

“Cleopatra and Antony” by Diana Preston, Amazon.com, well-written and engaging rehashing of the story;

“Antony and Cleopatra” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2010) Amazon.com, emphasizes the military side of their relationship.

“Cleopatra: A Life” by Stacy Schiff (2010) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra” by Diane Stanley (1998) Amazon.com;

“Cleopatra: the Last Queen of Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesly (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” by Toby Wilkinson (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome” by Michael Parenti Amazon.com;

“Julius Caesar” by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library) Amazon.com;

“The Ides: Caesar's Murder and the War for Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2010) Amazon.com;

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“Fall of the Roman Republic (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch Amazon.com;

“Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny” by Edward Watts (2020), Illustrated Amazon.com;

“The Fall of the Roman Republic: Roman History, Books 36-40 (Oxford World's Classics)

by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

Marc Antony's Early Life and Family

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “The grandfather of Antony was the famous pleader, whom Marius put to death for having taken part with Sylla. His father was Antony, surnamed of Crete, not very famous or distinguished in public life, but a worthy good man, and particularly remarkable for his liberality, as may appear from a single example. He was not very rich, and was for that reason checked in the exercise of his good nature by his wife. A friend that stood in need of money came to borrow of him. Money he had none, but he bade a servant bring him water in a silver basin, with which, when it was brought, he wetted his face, as if he meant to shave, and, sending away the servant upon another errand, gave his, friend the basin, desiring him to turn it to his purpose. And when there was, afterwards, a great inquiry for it in the house, and his wife was in a very ill-humour, and was going to put the servants one by one to the search, he acknowledged what he had done, and begged her pardon. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

young Marc Antony

“His wife was Julia, of the family of the Caesars, who, for her discretion and fair was not inferior to any of her time. Under her, Antony received his education, she being, after the death of his father, remarried to Cornelius Lentulus, who was put to death by Cicero for having been of Catiline's conspiracy. This, probably, was the first ground and occasion of that mortal grudge that Antony bore Cicero. He says, even, that the body of Lentulus was denied burial, till, by application made to Cicero's wife, it was granted to Julia. But this seems to be a manifest error, for none of those that suffered in the consulate of Cicero had the right of burial denied them.

“Antony grew up a very beautiful youth, but by the worst of misfortunes, he fell into the acquaintance and friendship of Curio, a man abandoned to his pleasures, who, to make Antony's dependence upon him a matter of greater necessity, plunged him into a life of drinking and dissipation, and led him through a course of such extravagance that he ran, at that early age, into debt to the amount of two hundred and fifty talents. For this sum Curio became his surety; on hearing which, the elder Curio, his father, drove Antony out of his house. After this, for some short time he took part with Clodius, the most insolent and outrageous demagogue of the time, in his course of violence and disorder; but getting weary before long, of his madness, and apprehensive of the powerful party forming against him, he left Italy and travelled into Greece, where he spent his time in military exercises and in the study of eloquence. He took most to what was called the Asiatic taste in speaking, which was then at its height, and was, in many ways, suitable to his ostentatious, vaunting temper, full of empty flourishes and unsteady efforts for glory. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

Antony’s Early Military Campaign in Syria

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “After some stay in Greece, he was invited by Gabinius, who had been consul, to make a campaign with him in Syria, which at first he refused, not being willing to serve in a private character, but receiving a commission to command the horse, he went along with him. His first-service was against Aristobulus, who had prevailed with the Jews to rebel. Here he was himself the first man to scale the largest of the works, and beat Aristobulus out of all of them; after which he routed in a pitched battle, an army many times over the number of his, killed almost all of them and took Aristobulus and his son prisoners. This war ended, Gabinius was solicited by Ptolemy to restore him to his kingdom of Egypt, and a promise made of ten thousand talents reward. Most of the officers were against this enterprise, and Gabinius himself did not much like it, though sorely tempted by the ten thousand talents. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

“But Antony, desirous of brave actions and willing to please Ptolemy, joined in persuading Gabinius to go. And whereas all were of opinion that the most dangerous thing before them was the march to Pelusium, in which they would have to pass over a deep sand, where no fresh water was to be hoped for, along the Acregma and the Serbonian marsh (which the Egyptians call Typhon's breathing-hole, and which is, in probability, water left behind by, or making its way through from, the Red Sea, which is here divided from the Mediterranean by a narrow isthmus), Antony, being ordered thither with the horse, not only made himself master of the passes, but won Pelusium itself, a great city, took the garrison prisoners, and by this means rendered the march secure to the army, and the way to victory not difficult for the general to pursue.

The enemy also reaped some benefit of his eagerness for honour. For when Ptolemy, after he had entered Pelusium, in his rage and spite against the Egyptians, designed to put them to the sword, Antony withstood him, and hindered the execution. In all the great and frequent skirmishes and battles he gave continual proofs of his personal valour and military conduct; and once in particular, by wheeling about and attacking the rear of the enemy, he gave the victory to the assailants in the front, and received for this service signal marks of distinction. Nor was his humanity towards the deceased Archelaus less taken notice of. He had been formerly his guest and acquaintance, and, as he was now compelled, he fought him bravely while alive, but on his death, sought out his body and buried it with royal honours. The consequence was that he left behind him a great name among the Alexandrians, and all who were serving in the Roman army looked upon him as a most gallant soldier.”

Antony’s Appearance and Character

older Marc Antony

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “He had also a very good and noble appearance; his beard was well grown, his forehead large, and his nose aquiline, giving him altogether a bold, masculine look that reminded people of the faces of Hercules in paintings and sculptures. It was, moreover, an ancient tradition, that the Antonys were descended from Hercules, by a son of his called Anton; and this opinion he thought to give credit to by the similarity of his person just mentioned, and also by the fashion of his dress. For, whenever he had to appear before large numbers, he wore his tunic girt low about the hips, a broadsword on his side, and over all a large coarse mantle. What might seem to some very insupportable, his vaunting, his raillery, his drinking in public, sitting down by the men as they were taking their food, and eating, as he stood, off the common soldiers' tables, made him the delight and pleasure of the army. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

In love affairs, also, he was very agreeable: he gained many friends by the assistance he gave them in theirs, and took other people's raillery upon his own with good-humour. And his generous ways, his open and lavish hand in gifts and favours to his friends and fellow-soldiers, did a great deal for him in his first advance to power, and after he had become great, long maintained his fortunes, when a thousand follies were hastening their overthrow. One instance of his liberality I must relate. He had ordered payment to one of his friends of twenty-five myriads of money or decies, as the Romans call it, and his steward wondering at the extravagance of the sum, laid all the silver in a heap, as he should pass by. Antony, seeing the heap, asked what it meant; his steward replied, "The money you have ordered to be given to your friend." So, perceiving the man's malice, said he, "I thought the decies had been much more; 'tis too little; let it be doubled." This, however, was at a later time.

Fulvia — Marc Antony’s Third Wife

According to Live Science: Born into a noble family around 83 B.C., Fulvia was influential in Rome around the time of Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 B.C. and built considerable personal wealth after she repeatedly became widowed. The earliest record of Fulvia describes the violent death of her first husband, a politician named Publius Clodius Pulcher. "When a riot broke out during his campaign for office, Clodius was beaten to death by a mob paid for by a rival, Titus Annius Milo," historian Lindsay Powell told All About History magazine. "Fulvia and his mother dragged the corpse to the Roman Forum and swore to avenge his death." [Source Live Science, October 23, 2021

In 49 B.C. her next husband, Gaius Scribonius Curio, was elected tribune, a powerful position in ancient Rome. Fulvia persuaded her deceased husband's followers to support Curio, said Joanne Ball, who has her doctorate in archaeology from the University of Liverpool in the U.K. "Fulvia was also adept at identifying the political mood within Rome, recognizing the value of allying with Julius Caesar and his populist cause, encouraging each of her husbands to form close links with Caesar," Ball said.

In 47 B.C., Fulvia married again — this time, to Mark Antony, Caesar's right-hand man. After Caesar's death three years later, Antony became one of three co-rulers of Rome, and the couple carried out a number of revenge killings, removing their political enemies, including politician Marcus Tullius Cicero. After Cicero's death in 43 B.C., Fulvia took the dead man's head, spat on it, took out the tongue and "pierced it with pins," according to Cassius Dio's "Roman History" (translation by Earnest Cary, through penelope.uchicago.edu).

The height of Fulvia's power was quickly followed by her downfall. In 42 B.C., Antony and his co-rulers left Rome to pursue Caesar's assassins, leaving Fulvia "de facto co-ruler of Rome," according to Ball. "In 41 B.C., in support of Antony's political ambitions, she opened hostilities with Octavian — Caesar's adopted son and Antony's main rival — raising eight legions in support of the cause," Ball said. "But by this stage, Antony's affections had been taken by Cleopatra of Egypt." Fulvia was defeated and died in 40 B.C., while exiled in Greece.

Marc Antony in Ephesus

Antony with Caesar on His Military Campaigns

During the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey, Antony campaigned with Caesar. Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “When the Roman state finally broke up into two hostile factions, the aristocratical party joining Pompey, who was in the city, and the popular side seeking help from Caesar, who was at the head of an army in Gaul, Curio, the friend of Antony, having changed his party and devoted himself to Caesar, brought over Antony also to his service. And the influence which he gained with the people by his eloquence and by the money which was supplied by Caesar, enabled him to make Antony, first, tribune of the people, and then, augur. And Antony's accession to office was at once of the greatest advantage to Caesar. In the first place, he resisted the consul Marcellus, who was putting under Pompey's orders the troops who were already collected, and was giving him power to raise new levies; he, on the other hand, making an order that they should be sent into Syria to reinforce Bibulus, who was making war with the Parthians, and that no one should give in his name to serve under Pompey.” [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

When “Caesar set his army in motion, and marched into Italy... Cicero writes in his Philippics that Antony was as much the cause of the civil war as Helen was of the Trojan. But this is but a calumny. For Caesar was not of so slight or weak a temper as to suffer himself to be carried away, by the indignation of the moment, into a civil war with his country, upon the sight of Antony and Cassius seeking refuge in his camp meanly dressed and in a hired carriage, without ever having thought of it or taken any such resolution long before. This was to him, who wanted a pretence of declaring war, a fair and plausible occasion; but the true motive that led him was the same that formerly led Alexander and Cyrus against all mankind, the unquenchable thirst of empire, and the distracted ambition of being the greatest man in the world, which was impracticable for him, unless Pompey were put down. So soon, then, as he had advanced and occupied Rome, and driven Pompey out of Italy, he proposed first to go against the legions that Pompey had in Spain, and then cross over and follow him with the fleet that should be prepared during his absence, in the meantime leaving the government of Rome to Lepidus, as praetor, and the command of the troops and of Italy to Antony, as tribune of the people. Antony was not long in getting the hearts of the soldiers, joining with them in their exercises, and for the most part living amongst them and making them presents to the utmost of his abilities; but with all others he was unpopular enough. He was too lazy to pay attention to the complaints of persons who were injured; he listened impatiently to petitions; and he had an ill name for familiarity with other people's wives. In short, the government of Caesar (which, so far as he was concerned himself, had the appearance of anything rather than a tyranny) got a bad repute through his friends. And of these friends, Antony, as he had the largest trust, and committed the greatest errors, was thought the most deeply in fault. Caesar, however, at his return from Spain, overlooked the charges against him, and had no reason ever to complain, in the employments he gave him in the war, of any want of courage, energy, or military skill.

“He himself, going aboard at Brundusium, sailed over the Ionian Sea with a few troops and sent back the vessels with orders to Antony and Gabinius to embark the army, and come over with all speed to Macedonia. Gabinius, having no mind to put to sea in the rough, dangerous weather of the winter season, was for marching the army round by the long land route; but Antony, being more afraid lest Caesar might suffer from the number of his enemies, who pressed him hard, beat back Libo, who was watching with a fleet at the mouth of the haven of Brundusium, by attacking his galleys with a number of small boats, and gaining thus an opportunity, put on board twenty thousand foot and eight hundred horse, and so set out to sea.

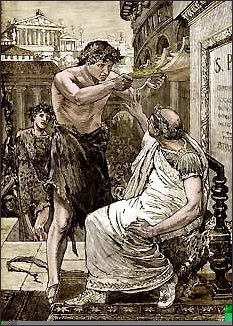

Caesar refuses the diadem from Marc Antony

And, being espied by the enemy and pursued, from this danger he was rescued by a strong south wind, which sprang up and raised so high a sea that the enemy's galleys could make little way. But his own ships were driving before it upon a lee shore of cliffs and rocks running sheer to the water, where there was no hope of escape, when all of a sudden the wind turned about to south-west, and blew from land to the main sea, where Antony, now sailing in security, saw the coast all covered with the wreck of the enemy's fleet. For hither the galleys in pursuit had been carried by the gale, and not a few of them dashed to pieces. Many men and much property fell into Antony's hands; he took also the town of Lissus, and, by the seasonable arrival of so large a reinforcement, gave Caesar great encouragement.

“There was not one of the many engagements that now took place one after another in which he did not signalize himself; twice he stopped the army in its full flight, led them back to a charge, and gained the victory. So that now without reason his reputation, next to Caesar's, was greatest in the army. And what opinion Caesar himself had of him well appeared when, for the final battle in Pharsalia, which was to determine everything, he himself chose to lead the right wing, committing the charge of the left to Antony, as to the best officer of all that served under him. After the battle, Caesar, being created dictator, went in pursuit of Pompey, and sent Antony to Rome, with the character of Master of the Horse, who is in office and power next to the dictator, when present, and in his absence the first, and pretty nearly indeed the sole magistrate. For on the appointment of a dictator, with the one exception of the tribunes, all other magistrates cease to exercise any authority in Rome.”

Antony and the Assassination of Caesar

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Brutus and Cassius, who in making choice of trusty friends... were thinking to engage Antony. The rest approved, except Trebonius, who told them that Antony and he had lodged and travelled together in the last journey they took to meet Caesar, and that he had let fall several words, in a cautious way, on purpose to sound him; that Antony very well understood him, but did not encourage it; however, he had said nothing of it to Caesar, but had kept the secret faithfully. The conspirators then proposed that Antony should die with him, which Brutus would not consent to, insisting that an action undertaken in defence of right and the laws must be maintained unsullied, and pure of injustice. It was settled that Antony, whose bodily strength and high office made him formidable, should, at Caesar's entrance into the senate, when the deed was to be done, be amused outside by some of the party in a conversation about some pretended business. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

“So when all was proceeded with, according to their plan, and Caesar had fallen in the senate-house, Antony, at the first moment, took a servant's dress, and hid himself. But, understanding that the conspirators had assembled in the Capitol, and had no further design upon any one, he persuaded them to come down, giving them his son as a hostage. That night Cassius supped at Antony's house, and Brutus with Lepidus. Antony then convened the senate, and spoke in favour of an act of oblivion, and the appointment of Brutus and Cassius to provinces. These measures the senate passed; and resolved that all Caesar's acts should remain in force. Thus Antony went out of the senate with the highest possible reputation and esteem; for it was apparent that he had prevented a civil war, and had composed, in the wisest and most statesmanlike way, questions of the greatest difficulty and embarrassment. But these temperate counsels were soon swept away by the tide of popular applause, and the prospect, if Brutus were overthrown, of being without doubt the ruler-in-chief. As Caesar's body was conveying to the tomb, Antony, according to the custom, was making his funeral oration in the market-place, and perceiving the people to be infinitely affected with what he had said, he began to mingle with his praises language of commiseration, and horror at what had happened, and, as he was ending his speech, he took the under-clothes of the dead, and held them up, showing them stains of blood and the holes of the many stabs, calling those that had done this act villains and bloody murderers. All which excited the people to such indignation, that they would not defer the funeral, but, making a pile of tables and forms in the very market-place, set fire to it; and every one, taking a brand, ran to the conspirators' houses, to attack them.

Antony After the Assassination of Caesar

Marc Antony and dead Caesar

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Brutus and his whole party left the city, and Caesar's friends joined themselves to Antony. Calpurnia, Caesar's wife, lodged with him the best part of the property to the value of four thousand talents; he got also into his hands all Caesar's papers wherein were contained journals of all he had done, and draughts of what he designed to do, which Antony made good use of; for by this means he appointed what magistrates he pleased, brought whom he would into the senate, recalled some from exile, freed others out of prison, and all this as ordered so by Caesar. The Romans, in mockery, gave those who were thus benefited the name of Charonites, since, if put to prove their patents, they must have recourse to the papers of the dead. In short, Antony's behaviour in Rome was very absolute, he himself being consul and his two brothers in great place; Caius, the one, being praetor, and Lucius, the other, tribune of the people. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

“While matters went thus in Rome, the young Caesar, Caesar's niece's son, and by testament left his heir, arrived at Rome from Apollonia, where he was when his uncle was killed. The first thing he did was to visit Antony, as his father's friend. He spoke to him concerning the money that was in his hands, and reminded him of the legacy Caesar had made of seventy-five drachmas of every Roman citizen. Antony, at first, laughing at such discourse from so young a man, told him he wished he were in his health, and that he wanted good counsel and good friends to tell him the burden of being executor to Caesar would sit very uneasy upon his young shoulders. This was no answer to him; and, when he persisted in demanding the property, Antony went on treating him injuriously both in word and deed, opposed him when he stood for the tribune's office, and, when he was taking steps for the dedication of his father's golden chair, as had been enacted, he threatened to send him to prison if he did not give over soliciting the people. This made the young Caesar apply himself to Cicero, and all those that hated Antony; by them he was recommended to the senate, while he himself courted the people, and drew together the soldiers from their settlements, till Antony got alarmed, and gave him a meeting in the Capitol, where, after some words, they came to an accommodation.

“That night Antony had a very unlucky dream, fancying that his right hand was thunderstruck. And, some few days after, he was informed that Caesar was plotting to take his life. Caesar explained, but was not believed, so that the breach was now made as wide as ever; each of them hurried about all through Italy to engage, by great offers, the old soldiers that lay scattered in their settlements, and to be the first to secure the troops that still remained undischarged. Cicero was at this time the man of greatest influence in Rome. He made use of all his art to exasperate the people against Antony, and at length persuaded the senate to declare him a public enemy, to send Caesar the rods and axes and other marks of honour usually given to proctors, and to issue orders to Hirtius and Pansa, who were the consuls, to drive Antony out of Italy. The armies engaged near Modena, and Caesar himself was present and took part in the battle.

Lepidus, Antony and Octavian

"Antony was defeated, but both the consuls were slain. Antony, in his flight, was overtaken by distresses of every kind, and the worst of all of them was famine. But it was his character in calamities to be better than at any other time. Antony, in misfortune, was most nearly a virtuous man. It is common enough for people, when they fall into great disasters, to discern what is right, and what they ought to do; but there are but few who in such extremities have the strength to obey their judgment, either in doing what it approves or avoiding what it condemns; and a good many are so weak as to give way to their habits all the more, and are incapable of using their using minds. Antony, on this occasion, was a most wonderful example to his soldiers. He, who had just quitted so much luxury and sumptuous living, made no difficulty now of drinking foul water and feeding on wild fruits and roots. Nay, it is related they ate the very bark of trees, and, in passing over the Alps, lived upon creatures that no one before had ever been willing to touch.

“The design was to join the army on the other side the Alps, commanded by Lepidus, who he imagined would stand his friend, he having done him many good offices with Caesar. On coming up and encamping near at hand, finding he had no sort of encouragement offered him, he resolved to push his fortune and venture all. His hair was long and disordered, nor had he shaved his beard since his defeat; in this guise, and with a dark coloured cloak flung over him, he came into the trenches of Lepidus, and began to address the army. Some were moved at his habit, others at his words, so that Lepidus, not liking it, ordered the trumpets to sound, that he might be heard no longer. This raised in the soldiers yet a greater pity, so that they resolved to confer secretly with him, and dressed Laelius and Clodius in women's clothes, and sent them to see him. They advised him without delay to attack Lepidus's trenches, assuring him that a strong party would receive him, and, if he wished it, would kill Lepidus. Antony, however, had no wish for this, but next morning marched his army to pass over the river that parted the two camps. He was himself the first man that stepped in, and, as he went through towards the other bank, he saw Lepidus's soldiers in great numbers reaching out their hands to help him, and beating down the works to make him way. Being entered into the camp, and finding himself absolute master, he nevertheless treated Lepidus with the greatest civility, and gave him the title of Father, when he spoke to him, and though he had everything at his own command, he left him the honour of being called the general. This fair usage brought over to him Munatius Plancus, who was not far off with a considerable force. Thus in great strength he repassed the Alps, leading with him into Italy seventeen legions and ten thousand horse, besides six legions which he left in garrison under the command of Varius, one of his familiar friends and boon companions, whom they used to call by the nickname of Cotylon.”

Antony Versus Octavian

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “As Cicero saw the situation, Antony was the more dangerous of the two (cf. the exchange between Cicero and Antony enclosed with ad Att. 14.13). He began to attack Antony in a series of speeches. These are magnificent examples of invective which he titled "Philippics" after Demosthenes' attacks on the Macedonian king. The central themes were that Antony was aiming for a dictatorship (though the title of dictator had been abolished by law at Antony's insistence), and (at least by the time of the 3rd Philippic, which was delivered on Dec. 20, 44) that the Optimates should rally behind Octavian. To this they eventually agreed, and Octavian was coopted into the Senate and granted a propraetor's imperium, while Antony came dangerously close to being declared a public enemy (App. BC 3. 8. 50-61). Legally this made Octavian subordinate to the consuls of 43, A. Hirtius and C. Vibius Pansa, whom he allowed to lead his legions to relieve Decimus Brutus at Mutina in the spring of 43. Notice what an unnatural position this was for Caesar's heir; for the moment he had the legal backing of the Senate, but his troops were being used to save one of Caesar's murderers. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Antony was defeated at Mutina, but managed to escape to Transalpine Gaul. The consul Hirtius had been killed in battle, and Pansa died soon after; this is significant because it left Octavian in sole command of the victorious legions by default (they refused to serve under Decimus Brutus). As a reward Octavian demanded the consulship, and at the same time he made it clear to the senate that he still considered Decimus Brutus, as well as M. Brutus (in Macedonia) and Cassius (in Syria) guilty as murderers, while Sextus Pompey (in Africa) would always be his enemy. For what followed this impasse Octavian himself deserves most of the blame, the low point in his career (it is not a coincidence that Livy waited until after the death of Augustus to publish books 121-140 of the Ab Urbe Condita, dealing with the years after 43 BC); Cicero and the senate were guilty only of continuing to underestimate him (cf. Cic. Ad Att. 16.14, of late November 44: Sed in isto iuvene, quamquam animi satis, auctoritatis parum est - there is in the boy, I admit, enough spirit — but not enough authority). [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“They took steps to return the senatorial oligarchy to power, notably with the granting of maius imperium (overall command) to Brutus and Cassius in the east. Perhaps more annoying, from Octavian's point of view, was the attempt (much of it at the urging of Cicero) to rehabilitate Sextus Pompey, who had escaped unharmed from the battles of Thapsus and Munda and continued to harass the Caesarians. The sources make much of the fact that a triumph for Mutina was awarded to Decimus Brutus (and denied to Octavian); if anything, this bit of pettiness only proves how shortsighted the senate had become, quibbling over the sort of triumph which should never have been even contemplated, much less awarded to the commander who had watched as others rescued him from Antony's encirclement. The noble tradition had been too long sullied by the celebration of victories over Roman enemies. In any case, Octavian would not wait; he marched on Rome and had himself elected consul for 42 BC (the first of 13). At 19 he was the youngest consul in the history of Rome. ^*^

Marc Antony in the Eastern Roman Empire

Octavian and Marc Antony briefly ruled the Roman Empire together as part of a triumvirate and then the two of them alone, with Octavian ruling over the Western Provinces and Marc Antony ruling over the Eastern Provinces. Fernando Lillo Redonet wrote in National Geographic History: In 42 B.C. Rome’s three most powerful men carved up the republic among them. The triumvirate of Lepidus, Octavian, and Mark Antony was an uneasy alliance after turbulent times. Placed in charge of the eastern provinces, Mark Antony found himself far from Rome and immersed in the Hellenistic culture he had always adored. It was a heady combination that drew him into the arms of Cleopatra, Egypt’s beguiling queen. [Source Fernando Lillo Redonet, National Geographic History, February 13, 2019]

As Antony journeyed to take up his new responsibilities, amorous adventures ranked low on his agenda. The triumvirate that ruled over Rome’s vast territories needed to urgently restructure the army in the east, secure new sources of military funding, and launch a punitive expedition against the Parthians to avenge a humiliating defeat in 53 B.C. Julius Caesar had been planning such an expedition before his assassination, and Antony was keen to be seen to continue his great mentor’s work. He also knew that a major victory against a foreign foe would greatly enhance his personal prestige and power.

Mark Antony’s interests, however, extended beyond Roman politics. He had a deep love of the Greek Hellenistic culture that Alexander the Great’s conquests had firmly embedded in the lands that now formed Rome’s eastern provinces. The abundant cultural distractions helped to alleviate the heavy cares of state, and Antony took full advantage as he toured his territories. Visiting Athens, he won the sobriquet “Dionysus the giver of joy,” and traveling in Asia Minor, he was met in Ephesus by a spectacular procession of men and women dressed as satyrs and priestesses of Bacchus, the Roman god of revelry. The citizens of Ephesus bestowed upon the Roman Antony the divine title of “Dionysus the benefactor.” (Learn more about Greek culture that Antony adored.)

Antony’s grand tour then took him to Tarsus, in modern-day southern Turkey. From here he dispatched a messenger to the Queen of Egypt, inviting her to a meeting in the city. This was politics, not pleasure, as Rome needed to tap into Egypt’s immense wealth, abundant grain supplies, and military strategic location. Cleopatra also had strong political reasons for meeting Antony. Winning the friendship of one of Rome’s most powerful men would bring closer links with the republic, consolidating her grip on the throne and perhaps even expanding her kingdom. Already playing a brilliant political game, Cleopatra delayed her departure, heightening Antony’s anticipation and ensuring the preparations were in place to make the Roman’s first encounter with Egypt’s queen one to remember.

Antony and Cleopatra

Cleopatra (69-30 B.C.) is one of the most famous women of all a time. A Greek Queen of Egypt, she played a major role in the extension of the Roman Empire and was a lover of Julius Caesar, the wife of Marc Antony and a victim of Augustus Caesar, the creator of the Roman Empire.

Cleopatra and Marc Antony began their famous love affair in Tarsus in Asia Minor.in 42 B.C., after the death of Caesar when Octavian and Antony were fighting a civil war for control of Rome. Cleopatra was 29 years old at the time and is said to have purposely delayed setting out to meet him to heighten Antony's expectations. When she finally announced she was coming she sent the message: “For the good and happiness of Asia I am coming for a Festive reception...Venus has come to revel with Bacchus” Her arrival in a boat with priceless purple sails was immortalized in Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra . Plutarch described it as an act of mockery.

According to Plutarch, Cleopatra arrived in Tarsus to meet Antony on a perfumed barge with purple sails. She was dressed as Aphrodite and was fanned by boys dressed like cupids. "Her rowers caressed the water with oars of silver which dipped in time to the music of the flute, accompanied by pipes and lutes...Instead of a crew the barge was lined with the most beautiful of her waiting women as Nerid and Graces, some at the steering oars, others at the tackles of the sails, and all the while indescribably rich perfume, exhaled from innumerable censers, was wafted from the vessel to the river banks."

See Separate Article: CLEOPATRA AND MARC ANTONY: ROMANCE, EVENTS, EXTRAVAGANCE europe.factsanddetails.com

Marc Antony offering a sacrifice

Antony’s Campaign Against the Parthians

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “After the treaty was completed, Antony despatched Ventidius into Asia, to check the advance of the Parthians, while he, as a compliment to Caesar, accepted the office of priest to the deceased Caesar. And in any state affair and matter of consequence, they both behaved themselves with much consideration and friendliness for each other. But it annoyed Antony that in all their amusements, on any trial of skill or fortune, Caesar (Octavian) should be constantly victorious. He had with him an Egyptian diviner, one of those who calculate nativities, who, either to make his court to Cleopatra, or that by the rules of his art he found it to be so, openly declared to him that though the fortune that attended him was bright and glorious, yet it was overshadowed by Caesar's; and advised him to keep himself as far distant as he could from that young man; "for your Genius," said he, "dreads his; when absent from him yours is proud and brave, but in his presence unmanly and dejected;" and incidents that occurred appeared to show that the Egyptian spoke truth. For whenever they cast lots for any playful purpose, or threw dice, Antony was still the loser; and when they fought game-cocks or quails, Caesar's had the victory. This gave Antony a secret displeasure, and made him put the more confidence in the skill of his Egyptian. So, leaving the management of his home affairs to Caesar, he left Italy, and took Octavia, who had lately borne him a daughter, along with him into Greece.

“Here, whilst he wintered in Athens, he received the first news of Ventidius's successes over the Parthians, of his having defeated them in a battle, having slain Labienus and Pharnapates, the best general their king, Hyrodes, possessed. For the celebrating of which he made public feast through Greece, and for the prizes which were contested at Athens he himself acted as steward, and, leaving at home the ensigns that are carried before the general, he made his public appearance in a gown and white shoes, with the steward's wands marching before; and he performed his duty in taking the combatants by the neck, to part them, when they had fought enough.

“When the time came for him to set out for the war, he took a garland from the sacred olive, and, in obedience to some oracle, he filled a vessel with the water of the Clepsydra to carry along with him. In this interval, Pacorus, the Parthian king's son, who was marching into Syria with a large army, was met by Ventidius, who gave him battle in the country of Cyrrhestica, slew a large number of his men, and Pacorus among the first. This victory was one of the most renowned achievements of the Romans, and fully avenged their defeats under Crassus, the Parthians being obliged, after the loss of three battles successively, to keep themselves within the bounds of Media and Mesopotamia. Ventidius was not willing to push his good fortune further, for fear of raising some jealousy in Antony, but turning his aims against those that had quitted the Roman interest, he reduced them to their former obedience. Among the rest, he besieged Antiochus, King of Commagene, in the city of Samosata, who made an offer of a thousand talents for his pardon, and a promise of submission to Antony's commands.

Parthian Empire

Antony’s Failure Against the Parthians

Plutarch wrote: Antony “sent Cleopatra to Egypt, and marched through Arabia and Armenia; and, when his forces came together, and were joined by those of his confederate kings (of whom there were very many, and the most considerable, Artavasdes, King of Armenia, who came at the head of six thousand horse and seven thousand foot), he made a general muster. There appeared sixty thousand Roman foot, ten thousand horse, Spaniards and Gauls, who counted as Romans; and, of other nations, horse and foot thirty thousand. And these great preparations, that put the Indians beyond Bactria into alarm, and made all Asia shake, were all we are told rendered useless to him because of Cleopatra. For, in order to pass the winter with her, the war was pushed on before its due time; and all he did was done without perfect consideration, as by a man who had no power of control over his faculties, who, under the effect of some drug or magic, was still looking back elsewhere, and whose object was much more to hasten his return than to conquer his enemies. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120): Life of Anthony (82-30 B.C.) For “Lives,” written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden MIT]

“For, first of all, when he should have taken up his winter-quarters in Armenia, to refresh his men, who were tired with long marches, having come at least eight thousand furlongs, and then having taken the advantage in the beginning of the spring to invade Media, before the Parthians were out of winter-quarters, he had not patience to expect his time, but marched into the province of Atropatene, leaving Armenia on the left hand, and laid waste all that country. Secondly, his haste was so great that he left behind the engines absolutely required for any siege, which followed the camp in three hundred wagons, and, among the rest, a ram eighty feet long; none of which was it possible, if lost or damaged, to repair or to make the like, as the provinces of the Upper Asia produce no trees long or hard enough for such uses. Nevertheless, he left them all behind, as a mere impediment to his speed, in the charge of a detachment under the command of Statianus, the wagon officer. He himself laid siege to Phraata, a principal city of the King of Media, wherein were that king's wife and children. And when actual need proved the greatness of his error, in leaving the siege-train behind him, he had nothing for it but to come up and raise a mound against the walls, with infinite labour and great loss of time. Meantime Phraates, coming down with a large army, and hearing that the wagons were left behind with the battering engines, sent a strong party of horse, by which Statianus was surprised, he himself and ten thousand of his men slain, the engines all broken in pieces, many taken prisoners, and among the rest King Polemon.

“This great miscarriage in the opening of the campaign much discouraged Antony's army, and Artavasdes, King of Armenia, deciding that the Roman prospects were bad, withdrew with all his forces from the camp, although he had been the chief promoter of the war. The Parthians, encouraged by their success, came up to the Romans at the siege, and gave them many affronts; upon which Antony, fearing that the despondency and alarm of his soldiers would only grow worse if he let them lie idle taking all the horse, ten legions, and three praetorian cohorts of heavy infantry, resolved to go out and forage, designing by this means to draw the enemy with more advantage to a battle. To effect this, he marched a day's journey from his camp, and finding the Parthians hovering about, in readiness to attack him while he was in motion, he gave orders for the signal of battle to be hung out in the encampment, but, at the same time, pulled down the tents, as if he meant not to fight, but to lead his men home again; and so he proceeded to lead them past the enemy, who were drawn up in a half-moon, his orders being that the horse should charge as soon as the legions were come up near enough to second them....

“The war was full of hardship for both sides, and its future course was still more to be dreaded. Antony expected a famine; for it was no longer possible to get provisions without having many men wounded and killed. Phraates, too, knew that his Parthians were able to do anything rather than to undergo hardships and encamp in the open during winter, and he was afraid that if the Romans persisted and remained, his men would desert him, since already the air was getting sharp after the summer equinox. He therefore contrived the following stratagem. 2 Those of the Parthians who were most acquainted with the Romans attacked them less vigorously in their forays for provisions and other encounters, allowing them to take some things, praising their valour, and declaring that they were capital fighting men and justly admired by their own king. After this, they would ride up nearer, and quietly putting their horses alongside the Romans, would revile Antony because, when Phraates wished to come to terms and spare so many such excellent men, Antony would not give him an opportunity, but sat there awaiting those grievous and powerful enemies, famine and winter, which would make it difficult for them to escape even though the Parthians should escort them on their way. [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

Fighting Between the Romans and Parthians

Parthian warrior

Plutarch wrote: “On the fifth day, however, Flavius Gallus, an efficient and able soldier in high command, came to Antony and asked him for more light-armed troops from the rear, and for some of the horsemen from the van, confident that he would achieve a great success. Antony gave him the troops, and when the enemy attacked, Gallus beat them back, not withdrawing and leading them on towards the legionaries, as before, but resisting and engaging them more hazardously. The leaders of the rear guard, seeing that he was being cut off from them, sent and called him back; but he would not listen to them. Then, they say, Titius the quaestor laid hold of his standards and tried to turn them back, abusing Gallus for throwing away the lives of so many brave men. But Gallus gave back the abuse and exhorted his men to stand firm, whereupon Titius withdrew. Then Gallus forced his way among the enemy in front of him, without noticing that great numbers of them were enveloping him in the rear. But when missiles began to fall upon him from all sides, he sent and asked for help. Then the leaders of the legionaries, among whom was Canidius, a man of the greatest influence with Antony, are thought to have made no slight mistake. For when they ought to have wheeled their entire line against the enemy, they sent only a few men at a time to help Gallus, and again, when one detachment had been overcome, sent out others, and so, before they were aware of it, they came near plunging the whole army into defeat and flight. But Antony himself speedily came with his legionaries from the van to confront the fugitives, and the third legion speedily pushed its way through them against the enemy and checked his further pursuit. [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

“There fell no fewer than three thousand, and there were carried to their tents five thousand wounded men, among whom was Gallus, who was pierced in front by four arrows. Gallus, indeed, did not recover from his wounds, but Antony went to see all the others and tried to encourage them, with tears of sympathy in his eyes. The wounded men, however, with cheerful faces, seized his hand and exhorted him to go away and take care of himself, and not to be distressed. They called him Imperator, and said that they were safe if only he were unharmed. For, to put it briefly, no other imperator of that day appears to have assembled an army more conspicuous for prowess, endurance, or youthful vigour. Nay, the respect which his soldiers felt for him as their leader, their obedience and goodwill, and the degree to which all of them alike — men of good repute or men of no repute, commanders or private soldiers — preferred honour and favour from Antony to life and safety, left even the ancient Romans nothing to surpass. And the reasons for this were many, as I have said before: his high birth, his eloquence, his simplicity of manners, his love of giving and the largeness of his giving, his complaisance in affairs of pleasure or social intercourse. And so at this time, by sharing in the toils and distresses of the unfortunate and bestowing upon them whatever they wanted, he made the sick and wounded more eager in his service than the well and strong.

“The enemy, however, who had been already worn out and inclined to abandon their task, were so elated by their victory, and so despised the Romans, that they even bivouacked for the night near their camp, expecting very soon to be plundering the empty tents and the baggage of runaways. At daybreak, too, they gathered for attack in far greater numbers, and there are said to have been no fewer than forty thousand horsemen, since their king had sent even those who were always arrayed about his person, assured that it was to manifest and assured success; for the king himself was never present at a battle. Then Antony, wishing to harangue his soldiers, called for a dark robe, that he might be more pitiful in their eyes. But his friends opposed him in this, and he therefore came forward in the purple robe of a general and made his harangue, praising those who had been victorious, and reproaching those who had fled. The former exhorted him to be of good courage, offered themselves to him for decimation,0 if he wished, or for any other kind of punishment; only they begged him to cease being distressed and vexed. In reply, Antony lifted up his hands and prayed the gods that if, then, any retribution were to follow his former successes, it might fall upon him alone, and that the rest of the army might be granted victory and safety.

“On the following day they went forward under better protection; and the Parthians met with a great surprise when they attacked them. For they thought they were riding up for plunder and booty, not battle, and when they encountered many missiles and saw that the Romans were fresh and vigorous and eager for the fray, they were once more tired of the struggle. However, as the Romans were descending some steep hills, the Parthians attacked them and shot at them as they slowly moved along. Then the shield-bearers wheeled about, enclosing the lighter armed troops within their ranks, while they themselves dropped on one knee and held their shields out before them. The second rank held their shields out over the heads of the first, and the next rank likewise. The resulting appearance is very like that of a roof, affords a striking spectacle, and is the most effective of protections against arrows, which glide off from it. The Parthians, however, thinking that the Romans dropping on one knee was a sign of fatigue and exhaustion, laid aside their bows, grasped their spears by the middle and came to close quarters. But the Romans, with a full battle cry, suddenly sprang up, and thrusting with their javelins slew the foremost of the Parthians and put all the rest to rout. This happened also on the following days as the Romans, little by little, proceeded on their way.

Defeat of the Romans by Parthians

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Famine also attacked the army, which could provide itself with little grain even by fighting, and was not well furnished with implements for grinding. These had been abandoned, for the most part, since some of the beasts of burden died, and the others had to carry the sick and wounded. It is said that one Atticº choenix of wheat brought fifty drachmas; and loaves of barley bread were sold for their weight in silver. Resorting, therefore, to vegetables and roots, they could find few to which they were accustomed, and were compelled to make trial of some never tasted before. Thus it was that they partook of an herb which produced madness, and then death. He who ate of it had no memory, and no thought of anything else than the one task of moving or turning every stone, as if he were accomplishing something of great importance. The plain was full of men stooping to the ground and digging around the stones or removing them; and finally they would vomit bile and die, since the only remedy, wine, was not to be had. Many perished thus, and the Parthians would not desist, and Antony, as we are told, would often cry: "O the Ten Thousand!" thereby expressing his admiration of Xenophon's army, which made an even longer march to the sea from Babylon, and fought with many times as many enemies, and yet came off safe. [Source: Parallel Lives by Plutarch, published in Vol. IX, of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1920, translated by Bernadotte Perrin]

“And now the Parthians, unable to throw the army into confusion or break up its array, but many times already defeated and put to flight, began once more to mingle peaceably with the men who went out in search of fodder or grain, and pointing to their unstrung bows would say that they themselves were going back, and that this was the end of their retaliation, although a few Medes would still follow the Romans one or two days' march, not molesting them at all, but merely protecting the more outlying villages. To these words they added greetings and acts of friendliness, so that once more the Romans became full of courage, and Antony, when he heard about it,

“But word was at once brought to the Parthians that Antony was advancing, and contrary to their custom they set out in pursuit while it was yet night. Just as the sun was rising they came up with the rear-guard of the Romans, which was foredone with sleeplessness and toil; for they had accomplished two hundred and forty furlongs in the night. Moreover, they did not expect that the enemy would come upon them so quickly, and were therefore disheartened. Besides, their contest intensified their thirst; for they had to ward off the enemy and make their way forward at the same time. Those who marched in the van came to a river, the water of which was clear and cold, but had a salty taste and was poisonous. This water, as soon as one drank it, caused pains, accompanied by cramping of the bowels and an inflammation of one's thirst. Of this too the Mardian had warned them, but none the less the soldiers forced aside those who tried to turn them back, and drank. Antony went round and begged the men to hold out a little while; for not far ahead, he said, there was another river which was potable, and then the rest of the way was too rough for cavalry, so that the enemy must certainly turn back. At the same time, too, he called his men back from fighting and gave the signal for pitching the tents, that the soldiers might at least enjoy the shade a little.

“Accordingly, the Romans went to pitching their tents, and the Parthians, as their custom was, at once began to withdraw. At this point Mithridates came again, and after Alexander had joined him he advised Antony to let the army rest only a little while, and then to get it under way and hasten to the river, assuring him that the Parthians would not cross it, but would continue the pursuit until they reached it. This message was carried to Antony by Alexander, who then brought out from Antony golden drinking-cups in great numbers, as well as bowls. Mithridates took as many of these as he could hide in his garments and rode off. Then, while it was still day, they broke camp and proceeded on their march. The enemy did not molest them, but they themselves made that night of all other nights the most grievous and fearful for themselves. For those who had gold or silver were slain and robbed of it, and the goods were plundered from the beasts of burden; and finally the baggage-carriers of Antony were attacked, and beakers and costly tables were cut to pieces or distributed about.

“And now, since there was great confusion and straggling throughout the whole army (for they thought that the enemy had fallen upon them and routed and dispersed them), Antony called one of the freedmen in his body-guard, Rhamnus by name, and made him take oath that, at the word of command, he would thrust his sword through him and cut off his head, that he might neither be taken alive by the enemy nor recognized when he was dead. Antony's friends burst into tears, but the Mardian tried to encourage him, declaring that the river was near: for a breeze blowing from it was moist, and a cooler air in their faces made their breathing pleasanter. He said also that the time during which they had been marching made his estimate of the distance conclusive; for little of the night was now left. At the same time, too, others brought word that the tumult was a result of their own iniquitous and rapacious treatment of one another. Therefore, wishing to bring the throng into order after their wandering and distraction, Antony ordered the signal to be given for encampment.

captive Parthians

“Day was already dawning, and the army was beginning to assume a certain order and tranquillity, when the arrows of the Parthians fell upon the rear ranks, and the light-armed troops were ordered by signal to engage. The men-at arms, too, again covered each other over with their shields, as they had done before, and so withstood their assailants, who did not venture to come to close quarters. The front ranks advanced little by little in this manner, and the river came in sight. On its bank Antony drew up his sick and disabled soldiers across first. And presently even those who were fighting had a chance to drink at their ease; for when the Parthians saw the river, they unstrung their bows and bade the Romans cross over with good courage, bestowing much praise also upon their valour. So they crossed without being disturbed and recruited themselves, and then resumed their march, putting no confidence at all in the Parthians. And on the sixth day after their last battle with them they came to the river Araxes, which forms the boundary between Media and Armenia. Its depth and violence made it seem difficult of passage; and a report was rife that the enemy were lying in ambush there and would attack them as they tried to cross. But after they were safely on the other side and had set foot in Armenia, as if they had just caught sight of that land from the sea, they saluted it and fell to weeping and embracing one another for joy. But as they advanced through the country, which was prosperous, and enjoyed all things in abundance after great scarcity, they fell sick with dropsies and dysenteries.

“There Antony held a review of his troops and found that twenty thousand of the infantry and four thousand of the cavalry had perished, not all at the hands of the enemy, but more than half by disease. They had, indeed, marched twenty-seven days from Phraata, and had defeated the Parthians in eighteen battles, but their victories were not complete or lasting because the pursuits which they made were short and ineffectual. And this more than all else made it plain that it was Artavasdes the Armenian who had robbed Antony of the power to bring that war to an end. For if the sixteen thousand horsemen who were led back from Media by him had been on hand, equipped as they were like the Parthians and accustomed to fighting with them, and if they, when the Romans routed the fighting enemy, had taken off the fugitives, it would not have been in the enemy's power to recover themselves from defeat and to venture again so often. Accordingly, all the army, in their anger, tried to incite Antony to take vengeance on the Armenian. But Antony, as a measure of prudence, neither reproached him with his treachery nor abated the friendliness and respect usually shown to him, being now weak in numbers and in want of supplies.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024