Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME

Roman women were somewhat better off than their housebound Greek counterparts. They could leave the house with chaperons, were allowed to socialize with their husband's house guests (Greek women were not) and they could attend public events like dramas and gladiator competitions although they usually had to sit in seats reserved for women. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

Roman women were somewhat better off than their housebound Greek counterparts. They could leave the house with chaperons, were allowed to socialize with their husband's house guests (Greek women were not) and they could attend public events like dramas and gladiator competitions although they usually had to sit in seats reserved for women. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

On exhibit titled ''I Claudia: Women In Ancient Rome' was held at the Yale University Art Gallery in 1996, The exhibit featured objects ranging from life-size marble portrait statues and reliefs to coins, jewelry and children's toys placed in historical, political and social contexts in three settings — a house, a forum and a cemetery representing the domestic, public and funerary realm. In Roman house with an atrium and fountain are statues of a family — mother, grandmother, children, even a dog. Nearby, children's toys are displayed, along with jewelry and marriage and divorce contracts. In the realm of the dead are funerary reliefs, commemorative urns and marble coffins.

Susan B. Matheson, curator of ancient art at the Yale Art Gallery, told the New York Times, ''Although women could not vote or hold office, they could own property and many were very wealthy. Some empresses dedicated temples, other buildings and statues of themselves. They were patrons of the arts.'' There is a sculpture of Livia (58 B.C.-A.D. 29), the first Roman Empress, and Augustus, the Emperor, and their sons. ''I like to think of the public realm as one in which we explore associative power — power that women got primarily through their connection to important men like the emperor,'' Ms. Kleiner said, pointing out a marble portrait of Antonia, daughter of Augustus's sister Octavia and Mark Antony, and also mother of the Empress Claudia, the fourth Empress of Rome. Elaborate hair styles, articulated in this and other portraits, are shown to be imbued with political and social messages, rather than simply being a matter of fashion. [Source: Bess Liebenson, New York Times, November 24, 1996]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROLES AND VIEWS OF WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIED LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT ROME: LAWS, TYPES, TRADITION factsanddetails.com ;

WEDDINGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LOVE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DIVORCE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Book: "Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity" by Sarah Pomeroy, a classics professor at Hunter College in New York; “The Roman Mother” (1988), “The Roman Family” (1992) and “Reading Roman” Women (2001) by Suzanne Dixon Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Women in Ancient Rome” by Paul Chrystal (2013) Amazon.com

“Women in Ancient Greece and Rome” (Cambridge Educational) by Michael Massey (1988) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of Women in Ancient Rome” (Greenwood Press) by Sara Elise Phang (2022) Amazon.com;

“A Week in the Life of a Greco-Roman Woman” by Holly Beers Amazon.com;

“Women and the Law in the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook on Marriage, Divorce and Widowhood” (Routledge) by Judith Evans Grubbs (2002) Amazon.com;

“Women in Roman Law and Society” by Jane F. Gardner (1991) Amazon.com;

“I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome” by E. E. Kleiner (1996) Amazon.com;

“Women and Politics in Ancient Rome” by Richard A. Bauman (1994) Amazon.com;

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation” by Maureen B. Fant and Mary R. Lefkowitz (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Missing Thread: A Women's History of the Ancient World” by Daisy Dunn (2024) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Women & Society in Greek & Roman Egypt” by Jane Rowlandson (1998) Amazon.com;

“Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher” by Edward J. Watts (2017)

Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Sources on Roman Women

Suzanne Dixon wrote for the BBC: “Where do we look for Roman women? The traditional answer has been - in Latin literature; that's to say in the histories, poems, biographies and political speeches composed by, and for, élite men. Few women, however, feature in this literature, and when they are included, it is often to make a point about modern morals or the importance of home life. These women are symbols, not 'real women'. [Source: Suzanne Dixon, BBC, March 29, 2011. Dixon is from Australia and has held lecturing positions at both the Australian National University and the University of Queensland. Her published books include The Roman Mother (1988), The Roman Family (1992) and Reading Roman Women (2001) |::|]

“State inscriptions are another possible source of information but, like Roman history books, they seldom mention women. Roman tombstones and statue bases celebrate women, but in a formulaic way (as do our modern-day equivalents), so they do not usually bring individual women to life for us, and it seems that all Roman children were sweet, all wives were chaste, all marriages were argument-free. |::|

“State inscriptions are another possible source of information but, like Roman history books, they seldom mention women. Roman tombstones and statue bases celebrate women, but in a formulaic way (as do our modern-day equivalents), so they do not usually bring individual women to life for us, and it seems that all Roman children were sweet, all wives were chaste, all marriages were argument-free. |::|

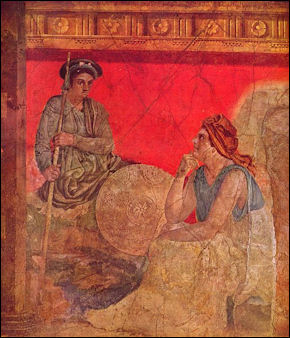

“And even when these ancient inscriptions do appeal to us, there is the possibility that we are over-influenced by a sentimental portrait, which leaves out all the complexities of living relationships. Roman paintings and sculpture present yet another avenue to the past. Women's portraits in the Roman tradition are often quite realistic, but they, too, fall into certain patterns, and sometimes individual heads seem to have been imposed on standard bodies. |::|

“Archaeology offers a different perspective, and Pompeii in particular is famous for having preserved for centuries, under lava, the details of the everyday life of the town. Nearby Herculaneum also shows us houses and flats, workplaces, bars and shops that are seldom even hinted at in the rather rarefied literature of Roman times. |::|

“Collecting evidence about Roman women's lives involves ranging over completely different kinds of information, and sifting each piece carefully, with due attention to the purpose of each source and the bias or ignorance of its author. A love poet, for example, wants to express his feelings about a real or imagined beloved, not to give you a rounded portrait of a real woman - while a son mourning his mother's death will mention only her virtues.” Also: “Bear in mind that the great majority of these sources are not authored or commissioned by women, but by men who are striving to make a particular point.” |::|

Women and of Roman Citizenship

Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: Citizenship, in the full sense, represented an individual’s ability to act freely in various areas of civic life. A Roman woman, however, did not have her own potestas (legal power or agency); she was subject to the authority of her father and then of her husband. If she was left without father or husband, she would come under the power of a male guardian who would take control of her property and carry out certain legal transactions for her. This male guardian had to grant formal consent for her actions. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

Clelia Martínez Maza wrote in National Geographic History: Citizenship, in the full sense, represented an individual’s ability to act freely in various areas of civic life. A Roman woman, however, did not have her own potestas (legal power or agency); she was subject to the authority of her father and then of her husband. If she was left without father or husband, she would come under the power of a male guardian who would take control of her property and carry out certain legal transactions for her. This male guardian had to grant formal consent for her actions. [Source Clelia Martínez Maza, National Geographic History, November 5, 2019]

Jurists of the time argued that this subjugation was legitimate due to the widely accepted prejudices of the time. Women were considered weaker, ignorant of legal matters, and lacking in judgment. Having no legal authority, women could not assume the role of head of the family. If they became widows they could not adopt children or exercise guardianship over any other member of the family, including their own children.

Although they were excluded from public office and politics, freeborn Roman women could claim some benefits of being a citizen. Female citizens could own assets, dispose of them as they wished, participate in contracts and manage their properties with complete autonomy, unless these activities required legal action, in which case the guardian had to intervene.

Some female citizens managed huge fortunes, such as those that appear in epigrams by the first century poet Martial. Taking a sardonic tone, Martial mainly depicts rich, childless widows, whom he mocks as easy prey for gold diggers. There is evidence, too, of wealthy female citizens running businesses in the provinces governed by Rome. The New Testament notes that Lydia, who welcomed Saint Paul and his companions to Phillipi (Macedonia), was involved with the lucrative purple-dying business.

Nevertheless, the inability of women to enjoy the same rights enjoyed by male citizens marked their lives from cradle to grave. These limitations are even reflected in their names. Unlike male citizens, women did not use the tria nomina, or three-part name. All the women from the same gens, or family, were called by a feminine or diminutive version of the male’s name. For example, the daughter of Claudius would be called Claudia. If Claudius had two daughters, the elder one would be Claudia Major, or Maxima, and the younger, Claudia Minor. If there were several sisters, ordinals could be used, Claudia Tertia, Claudia Quarta, etc.

Status of Women in Ancient Rome

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “Ancient Rome wasn’t an easy place to be a woman. Any hopes of being able to vote or of following a career was about as possible as a modern person trying to pluck a diamond out of thin air. Girls were sidelined to a life in the home and childbirth, suffering a philandering husband (if he was so inclined), and having little power in the marriage and no legal claim to her children. “However, because child mortality was so high, the state rewarded Roman wives for giving birth. The prize was perhaps what most women dearly wanted: legal independence. If a free-born woman managed three live births (four for a former slave), she was awarded with independent status as a person. Only by surviving this serial-birthing could a woman hope to escape being a man’s property and finally take control over her own affairs and life.”[Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016]

Edward Gibbon wrote in “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: “Experience has proved, that savages are the tyrants of the female sex, and that the condition of women is usually softened by the refinements of social life. In the hope of a robust progeny, Lycurgus had delayed the season of marriage: it was fixed by Numa at the tender age of twelve years, that the Roman husband might educate to his will a pure and obedient virgin. According to the custom of antiquity, he bought his bride of her parents, and she fulfilled the coemption by purchasing, with three pieces of copper, a just introduction to his house and household deities. A sacrifice of fruits was offered by the pontiffs in the presence of ten witnesses; the contracting parties were seated on the same sheep-skin; they tasted a salt cake of far or rice; and this confarreation, which denoted the ancient food of Italy, served as an emblem of their mystic union of mind and body. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part IV, “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

But this union on the side of the woman was rigorous and unequal; and she renounced the name and worship of her father's house, to embrace a new servitude, decorated only by the title of adoption, a fiction of the law, neither rational nor elegant, bestowed on the mother of a family (her proper appellation) the strange characters of sister to her own children, and of daughter to her husband or master, who was invested with the plenitude of paternal power. By his judgment or caprice her behavior was approved, or censured, or chastised; he exercised the jurisdiction of life and death; and it was allowed, that in the cases of adultery or drunkenness, the sentence might be properly inflicted. She acquired and inherited for the sole profit of her lord; and so clearly was woman defined, not as a person, but as a thing, that, if the original title were deficient, she might be claimed, like other movables, by the use and possession of an entire year. The inclination of the Roman husband discharged or withheld the conjugal debt, so scrupulously exacted by the Athenian and Jewish laws: but as polygamy was unknown, he could never admit to his bed a fairer or a more favored partner.

Positive Side of Being a Women in Ancient Rome

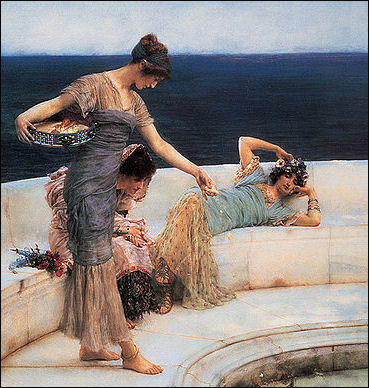

Silver Favourites by Alma-Tadema With her marriage the Roman woman reached a position not attained by the women of any other nation in the ancient world. No other people held its women in such high respect; nowhere else did women exert so strong and beneficent an influence. In her own house the Roman matron was absolute mistress. She directed its economy and supervised the tasks of the household slaves, but did no menial work herself. She was her children’s nurse, and conducted their early training and education. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Her daughters were fitted under their mother’s eye to be mistresses of similar homes, and remained her closest companions until she herself had dressed them for their bridal and their husbands had torn them from her arms. She was her husband’s helpmeet in business as well as in household matters, and he often consulted her on affairs of state. She was not confined at home to a set of so-called women’s apartments, as were her sisters in Greece; the whole house was open to her. She received her husband’s guests and sat at table with them. Even when she was subject to the manus of her husband, the restraint was so tempered by law and custom that she could hardly have been chafed by the fetters which had been forged with her own consent. |+|

“Out of the house the matron’s dress (stola matronalis) secured for its wearer profound respect. Men made way for her in the street; she had a place at the public games, at the theaters, and at the great religious ceremonies of state. She could give testimony in the courts, and until late in the Republic might even appear as an advocate. She often managed her own property herself. It is interesting to note that the first book of Varro’s work on farming is dedicated to his wife, and intended as a guide for her in the management of her own land. The matron’s birthday was sacredly observed and made a joyous occasion by the members of her household, and the people as a whole celebrated the Matronalia (the Roman “Mother’s Day”), the great festival on the first of March; presents were given to wives and mothers. Finally, if a woman came of a noble family, she might be honored, after she had passed away, with a public eulogy, delivered from the rostra in the Forum. |+|

Negative Side of Being a Women in Ancient Rome

It must be admitted that the education of women was not carried far at Rome, and that their accomplishments were few, and useful and homely rather than elegant. So far as accomplishments were concerned, however, their husbands fared no better. Even in our own country, restrictions on elementary education for women existed originally and were removed very slowly. For instance, it is told that in New Haven, in 1684, girls were forbidden to attend the grammar schools. |+|

“It must be admitted, too, that a great change took place in the last years of the Republic. With the laxness of the family life, the freedom of divorce, and the inflow of wealth and extravagance, the purity and dignity of the Roman matron declined, as the manhood and the strength of her father and her husband had declined before. It must be remembered, however, that ancient writers did not dwell upon certain subjects that are favorites with our own. The simple joys of childhood and domestic life, home, the praises of sister, wife, and mother may not have been too sacred for the poet and the essayist of Rome, but the essayist and the poet did not make them their themes; they took such matters for granted, and felt no need to dwell upon them. The mother of Horace may have been a singularly gifted woman, but she is never mentioned by her son. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The descriptions of domestic life, therefore, that have come down to us either are from Greek sources, or else they deal with precisely those circles where fashion, profligacy, and impurity made easy the work of the satirist. It is, therefore, safe to say that the pictures painted for us in the verse of Catullus and Juvenal, for example, were not true of Roman women as a class in the times of which they write. The strong, pure woman of the early day must have had many to imitate her virtues in the darkest times of the Empire. There were noble mothers then, as well as in the times of the Gracchi; there were wives as noble as the wife of Marcus Brutus.” |+|

Women’s Names in Ancient Rome

No very satisfactory account of the names of women can be given, because it is impossible to discover any system in the choice and arrangement of those that have come down to us. It may be said that the threefold name for women was unknown in the best days of the Republic; praenomina for women were rare and when used were not abbreviated. More common were the adjectives Maxima and Minor, and the numerals Secunda and Tertia, but these, unlike the corresponding names of men, seem always to have denoted the place of the bearer among a group of sisters. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

It was more usual for the unmarried woman to be called by her father’s nomen in its feminine form, with the addition of her father’s cognomen in the genitive case, followed later by the letter f (filia) to mark the relationship. An example is Caecilia Metelli. Caesar’s daughter was called Iulia, Cicero’s Tullia. Sometimes a woman used her mother’s nomen after her father’s. The married woman, if she passed into her husband’s “hand” (manus) by the ancient patrician ceremony, originally took his nomen, just as an adopted son took the name of the family into which he passed, but it cannot be shown that the rule was universally or even usually observed. Under the later forms of marriage the wife retained her maiden name. In the time of the Empire we find the threefold name for women in general use, with the same riotous confusion in selection and arrangement as prevailed in the case of the names of men at the same time.”

Manus: Power of the Husband Over His Wife

Women were regarded as the property of a man. When they reached marriageable age they had two options: to be married with “ manu” , which meant she belonged to her husband, or without “ manu”, in which she still belonged to her father and could inherit wealth for him or be repossessed by him.

The power over the wife possessed by the husband in its most extreme form, called by the Romans manus. By the oldest and most solemn form of marriage the wife was separated entirely from her father's family and passed into her husband's power or “hand” (conventio in manum). This assumes, of course, that he was sui iuris; if he was not, then she was, though nominally in his "hand," really subject, as he was, to his pater familias. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Any property she had of her own—and to have had any she must have been independent before her marriage—passed to her husband's father as a matter of course. If she had none, her pater familias furnished a dowry (dos), which shared the same fate, though it must be returned if she should be divorced. Whatever she acquired by her industry or otherwise while the marriage lasted also became her husband's (subject to the patria potestas under which he lived). So far, therefore, as property rights were concerned, manus differed in no respect from the patria potestas: the wife was in loco filiae, and on the husband's death took a daughter's share in his estate. |+|

“In other respects manus conferred more limited powers. The husband was required by law, not merely obliged by custom, to refer alleged misconduct of his wide to the iudicium domesticum, and this was composed in part of her cognates. He could put her away for certain grave offenses only; Romulus was said to have ordained that, if he divorced her without good cause, he should be punished with the loss of all his property. He could not sell her at all. In short, public opinion and custom operated even more strongly for her protection than for that of her children. It must be noticed, therefore, that the chief distinction between manus and patria potestas lay in the fact that the former was a legal relationship based upon the consent of the weaker party, while the latter was a natural relationship independent of all law and choice. |+|

Women’s Rights and Lack of Rights in Ancient Rome

Although women could not vote or hold office, they could own property. In the early days of the Roman Republic (509-27 B.C.) they had virtually no rights, at least spelled out in texts that are with us today. As time went on they obtained more rights. The Senate passed a law in 195 B.C. allowing women to ride in carriages and wear dyed clothes. Under Augustus (63 B.C.- A.D. 14), women had the right to divorce. The veiling of women was common practice among women in ancient Greece, Rome and Byzantium.

Edward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: “After the Punic triumphs, the matrons of Rome aspired to the common benefits of a free and opulent republic: their wishes were gratified by the indulgence of fathers and lovers, and their ambition was unsuccessfully resisted by the gravity of Cato the Censor. They declined the solemnities of the old nuptiais; defeated the annual prescription by an absence of three days; and, without losing their name or independence, subscribed the liberal and definite terms of a marriage contract. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part IV, “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

Of their private fortunes, they communicated the use, and secured the property: the estates of a wife could neither be alienated nor mortgaged by a prodigal husband; their mutual gifts were prohibited by the jealousy of the laws; and the misconduct of either party might afford, under another name, a future subject for an action of theft. To this loose and voluntary compact, religious and civil rights were no longer essential; and, between persons of a similar rank, the apparent community of life was allowed as sufficient evidence of their nuptials.

When the Roman matrons became the equal and voluntary companions of their lords, a new jurisprudence was introduced, that marriage, like other partnerships, might be dissolved by the abdication of one of the associates. In three centuries of prosperity and corruption, this principle was enlarged to frequent practice and pernicious abuse. Passion, interest, or caprice, suggested daily motives for the dissolution of marriage; a word, a sign, a message, a letter, the mandate of a freedman, declared the separation; the most tender of human connections was degraded to a transient society of profit or pleasure.

According to the various conditions of life, both sexes alternately felt the disgrace and injury: an inconstant spouse transferred her wealth to a new family, abandoning a numerous, perhaps a spurious, progeny to the paternal authority and care of her late husband; a beautiful virgin might be dismissed to the world, old, indigent, and friendless; but the reluctance of the Romans, when they were pressed to marriage by Augustus, sufficiently marks, that the prevailing institutions were least favorable to the males. A specious theory is confuted by this free and perfect experiment, which demonstrates, that the liberty of divorce does not contribute to happiness and virtue. The facility of separation would destroy all mutual confidence, and inflame every trifling dispute: the minute difference between a husband and a stranger, which might so easily be removed, might still more easily be forgotten; and the matron, who in five years can submit to the embraces of eight husbands, must cease to reverence the chastity of her own person.

Roman Men Feasted on Expensive Seafood While Women Ate Vegetables

Scientists at the University of York examined the remains of citizens of Herculaneum killed when Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79 and found that men got 50 per cent more of their dietary protein from seafood than women, indicating that Roman diets had a "clear distinction by sex". Women ate more fruit and vegetables, according to an examination of amino acids in the bones of Vesuvius victims, and were likely to have had less access to expensive fresh fish. [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, August 26, 2021]

“Prof Oliver Craig, of York's department of archaeology, said: "We found significant differences in the proportions of marine and terrestrial foods consumed between males and females, implying that access to food was differentiated according to gender." The study suggested that the difference stemmed from varying access to foodstuffs linked to "the different occupations held by men and women, cultural prohibitions or evidence of the uneven distribution of power".

“Silvia Soncin, who co-authored a paper published in Science Advance with Prof Craig, said, "Males were more likely to be directly engaged in fishing and maritime activities. They generally occupied more privileged positions in society and were freed from slavery at an earlier age, providing greater access to expensive commodities such as fresh fish."

Craig Simpson wrote in The Telegraph, “Men in Herculaneum — which was buried under volcanic ash following the eruption of Vesuvius — obtained a "strikingly higher" proportion of dietary protein from seafood than those now eating a modern Mediterranean diet. The male population in the ancient town also appear to have obtained more protein from cereals than their female counterparts. While women in the Roman period had more restricted access to seafood, they obtained their protein from other sources including meat, eggs, dairy, pulses and nuts.

“These discoveries were made by examining isotopes of carbon and nitrogen in the amino acids still present in the bones of 17 victims of the 340 people whose remains have been found at Herculaneum, which lies north of Pompeii. Both settlements and others in the area were struck by lethal pyroclastic flows, waves of searing hot ash, and buried under debris from Vesuvius when it erupted. The remains found at Herculaneum were unearthed on the beach and in stone vaults to which people had fled for shelter.

Literacy Among Women in Ancient Rome

Pepetua, a famous Christain martyr, wrote a famous prison diary

Many prominent historians have argued that few women in Rome could read or write, but research released in 2020 suggests otherwise. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: When it comes to ancient education and literacy, the consensus is that most people in the ancient Roman world were illiterate. Those who could read and write were wealthy elites; it was only because their families had enough money to pay for their education. What was true in general for ancient people was especially the case for women, who were almost never educated in the same way that their male siblings were. Now, a newly published article on archaeological evidence from an ancient Italian shrine dedicated to the "goddess of writing," argues that communal women’s education started much earlier than we knew. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, May 30, 2020]

Most of our evidence for literacy and education in the second — fourth centuries B.C. comes from Egypt. The few literary sources we have about education in the Roman Republic (roughly 509-27 B.C.) suggests that it was only elite boys who received an education and that early education like learning the alphabet and such took place in the home. Most scholars argue that systematic forms of education were imported from Greece later in the Republican period. In her article, “Education and Literacy in Ancient Italy: Evidence from the Dedications to the Goddess Reitia,” Katherine McDonald, of the University of Exeter, uses bronze offerings made to the northeastern Italian "goddess of writing" (Reitia) at her sanctuary in Este-Baratella (Veneto), to argue that “women were active participants in literacy and education” between 350-150 B.C.

A common feature of ancient religious practice was the depositing of votives — objects connected to the identity of a particular deity — in shrines related to particular deities. Pilgrims at temples dedicated to Asclepius, the god of healing for example, often took votives in the form of body parts. These were often offered to mark a particular milestone in a person’s life. In the case of Reitia, these votives include bronze writing implements and tablets that are inscribed with ancient writing exercises. It’s for this reason that Reitia is associated with literary practice at all. These exercises were the ancient equivalent of the cursive exercise books we use to educate children today. They often include a table of the alphabet or the repetition of single letters or syllables. What’s interesting about the writing-themed votives dedicated to Reitia, is that in many cases it was women, rather than men, who were dedicating these items. “[T]hese dedications,” argues McDonald, “provide evidence that some elite women at Este-Baratella were literate — or, at the very least, were active participants in a dedicatory practice which celebrated elementary literacy.”

Though some scholars have been dismissive of the possibility of literacy among even elite women, others have attempted to find hints of women’s literary and intellectual activity in what was otherwise a male-dominated Roman society. In her groundbreaking books Guardians of Letters and The Gendered Palimpsest, Cornell professor Kim Haines Eitzen, shows that at an elite level, women were an important part of ancient book cultures. While a great deal depends on the specific time period and geographical region under discussion, she told The Daily Beast; there’s evidence that women owned libraries, lent out books, wrote letters, and even functioned as scribes.

Even Some Female Slaves in Ancient Rome Could Read

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Chris Keith, a professor at St. Mary’s University, Twickenham, and author of Jesus’ Literacy, told me, “Although their numbers could not equal those of literate men and literate male slaves, literate females were known in early Christianity.” They weren’t just reading, though, some of them were brilliant copyists. One of the clearest examples of this, he told me, are the female calligraphers who worked for the prolific third century theologian Origen. “These women were not just literate,” said Keith, “but likely some of the most highly trained of the copyists in Origen's scribal workshop. They are mentioned as an aside, but their very presence raises important questions about the roles that otherwise unmentioned females might have played in the production of early Christian literature and manuscripts.” We also know from a scrap of papyrus found in Egypt (P.Oxy LXIII 4365) that early Christian women were exchanging literature with one another. “In short it is beyond a doubt that at least some the minority of literate early Christians were female.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, May 30, 2020]

A key element in this conversation is social status. When we talk about literacy, we almost always assume that only high-status wealthy Romans could read or write. But that picture is complicated by the fact that elite Romans rarely did their own paperwork. Instead they outsourced and depended upon the labor of literate slaves — whom they sometimes paid to educate themselves for this purpose — who worked as secretaries, copyists, notaries and lectors (or “readers”). Most of elite "writing" and "reading" was actually performed by slaves who took dictation, edited documents, and read aloud to their owners. This means that elite Roman women who did not have the skills necessary to write a letter themselves, even if they had received what Rafaella Cribbiore has called as an elementary education in basic literacy and numeracy, were able to "read" texts and use literate slaves to compose their own letters. The use of literate slaves doesn’t mean that their owners couldn’t read or write, but rather that they often chose not to. Moreover, they might have been the only way a person could continue to remain politically and socially engaged. Today, we have reading glasses, but for most people over the age 45, a lector would have been a necessity.

Additionally, some of these literate slaves were actually women. For elite women, a female slave was a more appropriate companion. Joseph Howley, as associate professor of classics at Columbia University, who has published extensively on slavery and ancient literary production, told The Daily Beast, “Often these enslaved readers were men, but funerary inscriptions from Rome also attest the prevalence of enslaved women who served as specially trained readers for aristocratic Roman men and women. These enslaved women … have traditionally been relegated to the literal footnotes of histories of Roman elite literacy. When our evidence shows us an enslaved woman reading out loud to the elite woman who owns her, we must think carefully about which of these women is engaged in “reading,” which of them we would call “literate,” and why.” Robyn Walsh, of the University of Miami, agreed and told me “The educated elite may in fact have been a target for this kind of enslavement in the aftermath of war as prisoners from Roman imperial campaigns were known to populate the households of the military and aristocratic victors.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024