Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

LOVE IN ANCIENT ROME

Jason and Medea

In the view of C.S. Lewis and some other scholars, romantic love did not emerge until relatively late, surfacing in the poems of French and Italian troubadours in the 11th and 12th centuries. But this theory does not seem to be born in evidence from Rome, where lovers were often described in myths and many poems and pieces of graffiti were expressions of love. One graffiti message went: “ ”Lovers, like bees, lead a honeyed life.”

Many pieces of love-related graffiti seem to have been written by love-struck young men. “ ”Girl,” reads an inscription found in a Pompeii bedroom, “ ”you’re beautiful I’ve been sent to you by one who is yours.” Others express missing a loved one in timeless fashion. “ ”Vibius Restitutus slept here alone, longing for Urbana.” Others expressed urgency. “ ”Driver,” one said. “ ”If you could feel the fires of love, you would hurry more to enjoy the pleasures of Venus. I love a younger charmer, please spur on the horses, let’s get on.”

The most famous love poets in Rome were by the naughty Catulus, the romantics Tibullus and Propertius, the epicist Virgil and the love laborer Ovid. Erotic love was seen by some Greeks and Romans it seems as an accursed thing that attacked its victims in painful, suffering way...and could even kill them. . The A.D. 2nd century physician Galen spent a great amount of time, refuting a popular idea that erotic seizures are caused by the attack of a god who holds burning torches to the victim.”

Roman-era skeletons buried in embrace, on top of a horse, were characterized as lovers but DNA analysis of the double burial in Austria revealed that a skeletal couple were likely an embracing mother and daughter.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT ROME: LAWS, TYPES, TRADITION factsanddetails.com ;

WEDDINGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

DIVORCE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMILY LIFE IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME: STATUS, INEQUALITY, LITERACY, RIGHTS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ROLES AND VIEWS OF WOMEN IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Love in Ancient Rome” by Pierre Grimal (1986) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Love” by Ovid Amazon.com;

“The Love Poems” by Ovid Amazon.com;

“Eros the Bittersweet” by Anne Carson (1986) Amazon.com;

“In the Orbit of Love: Affection in Ancient Greece and Rome” by David Konstan (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Wedding: Ritual and Meaning in Antiquity” by Karen Hersh (2010)

Amazon.com;

“Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian”

by Susan Treggiari (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Discourse of Marriage in the Greco-Roman World” by Jeffrey Beneker and Georgia Tsouvala (2020) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome” by Beryl Rawson (1996) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Sex and Death: The Family and the Fall of the Roman West” by Emma Southon (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Jane F. Gardner and Thomas Wiedemann (2013) Amazon.com;

“Women and the Law in the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook on Marriage, Divorce and Widowhood” (Routledge) by Judith Evans Grubbs (2002) Amazon.com;

“Women And Marriage During Roman Times Hardcover – May 22, 2010

by Maurice Pellison (1897) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Ovid and Love

Ovid is regarded as the premier Roman love poet. Brought up in the province to an equestrian family, he moved to Rome as a teenager and wrote about the sensuous life he enjoyed in upper class Roman society. Famed as a kind of Roman Casanova, he married three times, had a great many lovers and was involved in a highly-publicized sex scandal.

Ovid once wrote, "Offered a sexless heaven, I'd say no thank you, women are such sweet hell." He wrote that he learned about love from the mysterious Corinna who he rhapsodized about in his early “ Loves” . As a teenager he wrote they were "two adolescents, exploring a booby-trapped world of adult passions and temptations, and playing private games, first with their society, then — “ liaisons dangeruses” “ ”with one another."

Ovid was also a great storyteller. His “Metamorphosis” told the story of the Greek gods in a Roman context. He also poked fun of them. His irreverence helped led to the tossing of the Greek gods and replacing them with Roman ones. Ovid originated many versions of the myth stories we know today such as the King Midas, golden touch tale.

Ovid was also a great storyteller. His “Metamorphosis” told the story of the Greek gods in a Roman context. He also poked fun of them. His irreverence helped led to the tossing of the Greek gods and replacing them with Roman ones. Ovid originated many versions of the myth stories we know today such as the King Midas, golden touch tale.

In the “Art of Love”, a carefully crafted "seducer's manual," Ovid wrote:

” Love is a kind of war, and no assignment for cowards.

Where those banners fly, heroes are always on guard.

Soft, those barracks? They know long marches, terrible weather.

Night and winter and storm, grief and excessive fatigue.

Often the rain pelts down from the drenching cloudbursts of heaven.

Often you lie on the ground, wrapped in a mantle of cold.

If you are ever caught, no matter how well you've concealed it.

Though it is clear as the day, swear up and down it's a lie.

Don't be too abject, and don't be too unduly attentive.

That would establish your guilt far beyond anything else.

Wear yourself out if you must, and prove, in her bed, that you could not

Possibly be that good, coming from some other girl.

See Separate Article: POETRY OF ANCIENT ROME BY OVID, HORACE, SULPICIA, CATULLUS AND MARTIAL europe.factsanddetails.com

Love, Relatives and Marriage on Ancient Rome

Edward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”:“The freedom of love and marriage was restrained among the Romans by natural and civil impediments. An instinct, almost innate and universal, appears to prohibit the incestuous commerce of parents and children in the infinite series of ascending and descending generations. Concerning the oblique and collateral branches, nature is indifferent, reason mute, and custom various and arbitrary.[Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part IV,“Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

In Egypt, the marriage of brothers and sisters was admitted without scruple or exception: a Spartan might espouse the daughter of his father, an Athenian, that of his mother; and the nuptials of an uncle with his niece were applauded at Athens as a happy union of the dearest relations. The profane lawgivers of Rome were never tempted by interest or superstition to multiply the forbidden degrees: but they inflexibly condemned the marriage of sisters and brothers, hesitated whether first cousins should be touched by the same interdict; revered the parental character of aunts and uncles, and treated affinity and adoption as a just imitation of the ties of blood.

According to the proud maxims of the republic, a legal marriage could only be contracted by free citizens; an honorable, at least an ingenuous birth, was required for the spouse of a senator: but the blood of kings could never mingle in legitimate nuptials with the blood of a Roman; and the name of Stranger degraded Cleopatra and Berenice, to live the concubines of Mark Antony and Titus. This appellation, indeed, so injurious to the majesty, cannot without indulgence be applied to the manners, of these Oriental queens.

Love Between Husband and Wife in Ancient Rome

One wife wrote her husband, who was away: "Send for me — if you don't I'll die without seeing you daily. How I wish I could fly and come to see you...It tortures me not to see you."

Another wife, whose husband had entered a sanctuary wrote him: "When I received your letter...in which you announce that you have become a recluse in the Sarapis temple at Memphis, I immediately thanked the gods that you are well, but you are not coming here when all other recluses have come home, I do not like this one bit.”

David Konstan, a classic professor at Brown University, told U.S. News and World Report: “ ”It was taken for granted that if the husband and wife treated each other properly, love would develop and emerge, and by the end of their lives it would be a deep, mutual feeling.” Displays of affection however were regarded with soem scorn. One senator was stripped of his seat because he embraced his wife in public.

On one epitaph a man wrote to his wife, apparently thanking her for help escaping capture for some crime: “You furnished most ample means for my escape. With your jewels you aided me when you took off all the gold and pearls from your person, and gave them over to me. And promptly, with slaves, money, and provisions, having cleverly deceived the enemies’ guards, you enriched my absence.”

Pliny the Younger’s Love for His Third Wife

Gaius Plinius Caecilius (A.D. 61 – 113) — better known as Pliny the Younger — was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. He wrote hundreds of letters, of which 247 survived, and which are of great historical value. On the wife of his old friend Macrinus, Pliny the Younger wrote that she "would have been worthy to set an example, even if she had lived in olden times; she has lived with her husband thirty-nine years without a quarrel, or a fit of sulks, in unclouded happiness and mutual respect." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Pliny himself seems to have tasted perfect happiness in his marriage with his third wife, Calpurnia. He lavishes praise on her, boasting in turn of her tact, her reserve, her love, her faithfulness, and the taste for literature which had sprung from her sympathy for him. "How full of solicitude is she when I am entering upon any cause ! How kindly does she rejoice with me when it is over!" She never wearies of reading and rereading him and learning him by heart. When he gives a public reading she attends behind a curtain, "and greedily overhears my praises. She sings my verses and sets them to her lyre with no other master but Love, the best instructor."

Thus Calpurnia at her literary husband's side foreshadows the modern type of wife who is her husband's partner. Her collaboration is wholly free from pedantry and enhances instead of impairs the charm of her youth, the freshness of the love she feels for her husband and which he returns. The shortest of separations seems to have caused actual pain to both. When Pliny had to go away, Calpurnia sought him in his works, caressed them, and put them in the places where she was accustomed to see him. And Pliny for his part when Calpurnia is absent takes up her letters again and again, as if they had but newly arrived. At night he sees her beloved image in waking dreams, and "his feet carry him of their own accord" to the room where she usually lived, "but not finding you there, I return with as much sorrow and disappointment as an excluded lover." ss

Reading these affectionate letters, we are tempted to rebel against the pessimism of La Rochfoucauld and to deny the truth of his maxim that there was no such thing as a delightful marriage. On reflection, however, we begin to suspect that a trace of convention pervades these somewhat self-conscious and literary effusions. In Pliny's world, marriages were contracted rather from considerations of their suitability than from strength of feeling. He cannot have chosen his wife in a spirit very different from that in which he accepts the commission to look out for a suitable husband for the niece of a friend: with an eye not only to the physical and moral attributes of the young man, but also to his fortune and family connections; "for," he confesses, "I admit that these things certainly claim some notice: Ne id quidem praetereundum esse videtur"

What he seems most to have loved in Calpurnia was her admiration for his writings, and we soon come to the conclusion that he was readily consoled for the absences he complains of by the pleasure of polishing the phrases in which he so gracefully deplores them. For, after all, even when the couple were living under the same roof they were not together. They had, as. we should say, their separate rooms. Even amid the peace of his Tuscan villa, Pliny's chief delight was in a solitude favorable to his meditations, and it was his secretary (notarius), not his wife, whom he was wont to summon to his bedside at dawn. His conjugal affection was for him a matter of good taste and savoir vivre, and we cannot avoid the conviction that, taken all round, it was gravely lacking in warmth and intimacy.

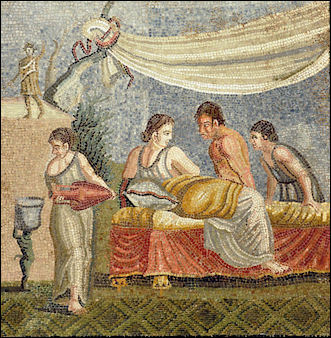

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024