Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

ELITE GLADIATORS

Andrew Fitzgerald wrote for Listverse: Gladiators were the athletic superstars of Ancient Rome. Their battles in the arena drew thousands of fans, often including the most important men of the day....Successful gladiators gained thousands of supporters, enjoyed lavish gifts, and could even be awarded freedom if they’d tallied up enough victories. Described below are some gladiators who all experienced glory and fame—both in and out of the arena—in Ancient Rome. [Source: Andrew Fitzgerald, Listverse April 2, 2013 ]

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine“Top gladiators were folk heroes with nicknames, fan clubs and adoring groupies. The story goes that Annia Galeria Faustina, the wife of Marcus Aurelius, was smitten with a gladiator she saw on parade and took him as a lover. Soothsayers advised the cuckolded emperor that he should have the gladiator killed, and that Faustina should bathe in his blood and immediately lie down with her husband. If the never reliable Scriptores Historiae Augustae is to be believed, Commodus’ obsession with gladiators stemmed from the fact that the murdered gladiator was his real dad. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2016]

Priscus and Verus were two rivals. Not much is known about them but their final fight was well-documented. They fought in the A.D. First Century at the famous Flavian Amphitheatre. After a spirited battle which last a long time, the two gladiators laid down their swords at the same time, conceded to each other and showing respect to their rival. The crowd applauded wildly, and the Emperor Titus awarded both men with the rudis, a small wooden sword given to gladiators upon their retirement. Side by side, the two combatants left the theater as free men.

Grave stelas belonging to gladiator heroes have been unearthed Anatolian cities. Tolga İldun wrote in Archaeology magazine: A stela from Hierapolis, commissioned by a woman named Marcellina for her first-class gladiator husband, Nikephoros, meaning “Bearer of Victory,” depicts the fighter holding a palm branch. An inscription on a grave stela belonging to the murmillo Droseros found in Stratonicea reads: “The man who killed me was once on the stage but now in the arena as Achilles, brought down by the games of Fate herself, Moira.” To mark his victories, Droseros was honored with 17 wreaths, which are shown on the stela. His fellow townsman, the plurimarum palmarum, or winner of many victories, Polydeukes, also known by his stage name, Vitalius, was commemorated with 15 wreaths and a palm branch, symbolizing his victories. His epitaph reads: “Here lies Vitalius, a brave man in boxing; Polydeukes, strong and true to his name, skilled in boxing, slain in the arena by his own hand.” [Source Tolga İldun, Archaeology magazine, November-December, 2024 archaeology.org]

RELATED ARTICLES:

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: THEIR LIVES, DIETS, HOMES AND GLORY europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR SCHOOLS AND TRAINING europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: HISTORY, IMPORTANCE AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

Film “Gladiator”, with Russel Crowe, directed by Ridley Scott (2000) DVD Amazon.com;

“The Way of the Gladiator: Inspiration for the Gladiator Films” by Daniel P. Mannix (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Real Gladiator: The True Story of Maximus Decimus Meridius” by Tony Sullivan (2022) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” by Howard Fast (1951) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” DVD with Kirk Douglas as Spartacus, Laurence Olivier, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1960) Amazon.com;

“The Spartacus War” by Barry S. Strauss (2009) Amazon.com

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: 100 BC–AD 200" by Stephen Wisdom, Angus McBride (Illustrator) (2001) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators 1st–5th centuries AD” by François Gilbert, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator), (2024) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: Deadly Arena Sports of Ancient Rome” by Christopher Epplett (2017) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Roman World” by Sandra R. Joshel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Society at Rome” by Keith Bradley (1994) Amazon.com;

Famous Gladiators

Tetraites is known from graffiti found in Pompeii in 1817. Andrew Fitzgerald wrote for Listverse: Tetraites was documented for his spirited victory over Prudes. Fighting in the murmillones style, he wielded a sword, a rectangle shield, a helmet, arm guards, and shin guards. The extent of his fame was not fully comprehended until the late Twentieth Century, when pottery was found as far away as France and England which depicted Tetraites’ victories. [Source: Andrew Fitzgerald, Listverse April 2, 2013 ]

Spiculus, another renowned gladiator of the First Century AD, enjoyed a particularly close relationship with the (reportedly) evil Emperor Nero. Following Spiculus’ numerous victories, Nero awarded him with palaces, slaves, and riches beyond imagination. When Nero was overthrown in AD 68, he urged his aides to find Spiculus, as he wanted to die at the hands of the famous gladiator. But Spiculus couldn’t be found, and Nero was forced to take his own life.

Marcus Attilius: Though a Roman citizen by birth, Attilius chose to enter gladiator school in an attempt to absolve the heavy debts he had incurred during his life. In his first battle he defeated Hilarus, a gladiator owned by Nero, who had won thirteen times in a row. Attilius then went on to defeat Raecius Felix, who had won twelve battles in a row. His feats were narrated in mosaics and graffiti discovered in 2007.

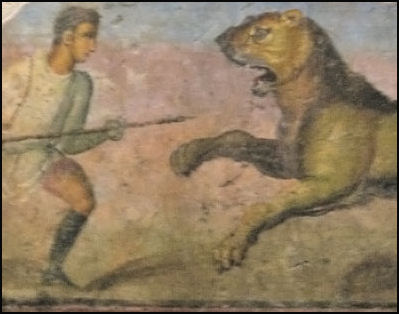

Carpophorus: While other gladiators on this list are known for their hand-to-hand combat against other humans, Carpophores was a famed Bestiarius. These gladiators fought exclusively against wild animals, and as such had very short-lived careers. Fighting at the initiation of the Flavian Amphitheatre, Carpophores famously defeated a bear, lion, and leopard in a single battle. In another battle that day, he slaughtered a rhinoceros with a spear. In total, it is said that he killed twenty wild animals that day alone, leading fans and fellow gladiators to compare Carpophorus to Hercules himself.

Carpophorus: While other gladiators on this list are known for their hand-to-hand combat against other humans, Carpophores was a famed Bestiarius. These gladiators fought exclusively against wild animals, and as such had very short-lived careers. Fighting at the initiation of the Flavian Amphitheatre, Carpophores famously defeated a bear, lion, and leopard in a single battle. In another battle that day, he slaughtered a rhinoceros with a spear. In total, it is said that he killed twenty wild animals that day alone, leading fans and fellow gladiators to compare Carpophorus to Hercules himself.

Crixus, a Gallic gladiator, was the right-hand man of the number one entry on this list. He enjoyed notable success in the ring, but resented his Lanista—the leader of the gladiator school and his “owner.” So after escaping from his gladiator school, he fought in a slave rebellion, helping to defeat large armies amassed by the Roman Senate with relative ease. After a dispute with the rebellion leader, however, Crixus and his men split off from the main group, seeking to destroy Southern Italy. This maneuver diverted enemy military forces from the main group, giving them valuable time to escape. Unfortunately, the Roman legions struck Crixus down before he could exact his revenge on the people who had oppressed him for so long.

Flamma, a Syrian slave, died at the age of thirty—having fought thirty-four times and having won twenty-one of those bouts. Nine battles ended in a draw, and he was defeated just four times. Most notably, Flamma was awarded the rudis a total of four times. When the rudis was given to a gladiator, he was usually freed from his shackles, and allowed to live normally among the Roman citizens. But Flamma refused the rudis, opting instead to continue fighting.

Commodus: the Emperor in the film Gladiator

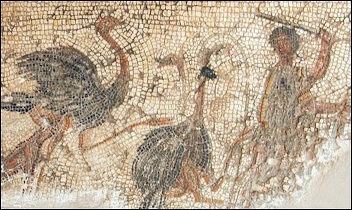

Commodus was the emperor depicted in the film Gladiator. He occasionally appeared in the arena during gladiator battles. He never put his life in danger and battled gladiators; instead he liked to decapitate ostriches with crescent-headed arrows. The crowds liked the show. They cheered and roared with laughter as the ostrich continued to run around after their heads were cut off. Once Commodus chopped off the head of an ostrich, and brandished its bloodied head and told senators the same fate awaited them if they went against him. Commodus enjoyed slaughtering other animals. He reportedly killed more than 100 bears in a single day.

killing ostriches on the Zilten mosaic

Andrew Fitzgerald wrote for Listverse: “Commodus enjoyed battling gladiators as often as possible. A narcissistic egomaniac, Commodus saw himself as the greatest and most important man in the world. He believed himself to be Hercules—even going so far as to don a leopard skin like that famously worn by the mythological hero. But in the arena, Commodus usually fought against gladiators who were armed with wooden swords, and slaughtered wild animals that were tethered or injured. [Source: Andrew Fitzgerald, Listverse April 2, 2013 ]

“As you could guess, most Romans therefore did not support Commodus. His antics in the arena were seen as disrespectful, and his predictable victories made for a poor show. In some instances, he captured disabled Roman citizens, and slaughtered them in the arena. As a testament to his narcissism, Commodus charged one million sesterces for every appearance—although he was never exactly “invited” to appear in the arena. Commodus was assassinated in AD 192, and it is believed that his actions as a “gladiator” encouraged his inner-circle to carry out the assassination.

See Separate Article: MARCUS AURELIUS: LIFE, LEADERSHIP, MEDITATIONS, COMMODUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Commodus’s Career as a Gladiator

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: ““Commodus was a gladiator manqué who may have acquired his taste for the sport during a period in his youth ( A.D. 171 to 173), some of which was misspent in Carnuntum in Austria. “Following in the (rumored) tradition of the emperors Caligula, Hadrian and Lucius Verus — and to the contempt of the patrician elite — Commodus often competed in the arena. He once awarded himself a fee of a million sestertii (brass coins) for a performance, straining the Roman treasury. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2016]

“According to Frank McLynn, Commodus performed “to enhance his claim to be able to conquer death, already implicit in his self-deification as the god Hercules.” Wrapped in lion skins and shouldering a club, the mad ruler would galumph around the ring à la Fred Flintstone. At one point, citizens who had lost a foot through accident or disease were tethered for Commodus to flog to death while he pretended they were giants. He chose for his opponents members of the audience who were given only wooden swords. Not surprisingly, he always won.

“Enduring his wrath was only marginally less injurious to health than standing in the path of an oncoming chariot. On pain of death, knights and senators were compelled to watch Commodus do battle and to chant hymns to him. It’s a safe bet that if Commodus had enrolled in Carnuntum’s gladiator school, he would have graduated summa cum laude.

Gladiator — The Film

One of the most famous depictions of gladiators is Ridley Scott's 2000 film "Gladiator", in which the emperor's son Commodus (played by Joaquin Phoenix), seeks revenge after his father chooses a celebrated general, Maximus (played by Russell Crowe), to succeed him on the throne. Commodus was a real emperor but his life is dramatized. One thing that is true though is Commodus did indeed love gladiator fighting and did fight himself, but, similar to his bout with Maximus in the film, he didn't fight fair. For example, according to the History Channel, he Commodus fought against men who had lost their feet or had to fight with sponges instead of rocks as weapons. [Source: BuzzFeed, September 20, 2023]

In the movie Gladiator, Marcus Aurelius was played by Richard Harris Contrary to impression given by the movie, Aurelius did no try to restore the republic, he had no general name Maximus and he was not killed by his son Commodus although the historian Cassius Dion said he was killed by doctors who wanted to “do a favor” for Commodus (most historians believe he died of an illness).

“Those About to Die” is 1958 book by Daniel P Mannix, which previously served as the original inspiration for the Gladiator screenwriter David Franzoni. The book and a television series based on it explores the ways in which Vespasian sought to restore order to Rome after the disastrous rule of Nero.

Film: "Gladiator", directed by Ridley Scott and starring Russell Crowe.

Spartacus

Spartacus (died 71 B.C.), a slave from Thrace trained to be a gladiator, is arguably the most famous gladiator of all time. From what little we know about him he fought gladiator battles mostly in the Pompeii and Naples area before launching the rebellion.. He left behind no testimony of his own. Most of the sources that wrote about him and his rebellions where upper class members who regarded slaves as subhuman and viewed a slave rebellion as a horror of horrors. Tom Holland, an author of books on Rome, wrote in the Washington Post, “Despite the terror he inspired, there was a quality to Spartacus that even the Romans seemed sneakily to have admired. Whether he was overpowering his guards or putting consuls to flight to killing his horse to deprive himself of any means of flight when he finally faced defeat he lived “fortissime” — as a man of exceptional courage."

1956 Stanley Kubrick film

Andrew Fitzgerald wrote for Listverse: “Spartacus was a Thracian soldier who had been captured and sold into slavery. Lentulus Batiatus of Capua must have recognized his potential, for he purchased him with the intention of turning him into a gladiator. In 73 B.C., Spartacus persuaded seventy of his fellow gladiators—Crixus included—to rebel against Batiatus. This revolt left their former owner murdered in the process, and the gladiators escaped to the slopes of nearby Mount Vesuvius. While in transit, the group set free many other slaves—thereby amassing a large and powerful following. The gladiators spent the winter of 72 BC training the newly freed slaves in preparation for what is now known as the Third Serville War, as their ranks swelled to as many as 70,000 individuals. Whole legions were sent to kill Spartacus, but these were easily defeated by the fighting spirit and experience of the gladiators. In 71 BC, Marcus Licinius Crassus amassed 50,000 well-trained Roman soldiers to pursue and defeat Spartacus. Crassus trapped Spartacus in Southern Italy, routing his forces, and killing Spartacus in the process. Six thousand of his followers were captured and crucified, their bodies made to line the road from Capua to Rome.” [Source: Andrew Fitzgerald, Listverse April 2, 2013]

Appian wrote: “Spartacus, a Thracian by birth, who had once served as a soldier with the Romans, but had since been a prisoner and sold for a gladiator, and was in the gladiatorial training-school at Capua,” Plutarch said: One Lentulus Batiates trained up a great many gladiators in Capua, most of them Gauls and Thracians, who, not for any fault by them committed, but simply through the cruelty of their master, were kept in confinement for the object of fighting one with another.”

Florus (A.D. c. 74 - c. 130) wrote in “Epitome of Roman History”: “Nor did he, who of a mercenary Thracian had become a Roman soldier, of a soldier a deserter and robber, and afterwards, from consideration of his strength, a gladiator, refuse to receive them. He afterwards, indeed, celebrated the funerals of his own officers, who died in battle, with the obsequies of Roman generals, and obliged the prisoners to fight with arms at their funeral piles, just as if he could atone for all past dishonour by becoming, from a gladiator, an exhibitor of shows of gladiators. [Source: Florus (A.D. c. 74 - c. 130 ), “Epitome of Roman History,” 8.20]

Spartacus became a symbol to what slaves and slaveowners feared most. Historians and observers have wondered what his motivations were: whether he was fighting for principal or freedom or was simply trying to grab his share of the loot. Barry Strauss, author of a book on the Spartacus wars, wrote that perhaps he died for “honor, power, vengeance, loot and even the favor of the gods."

RELATED ARTICLE: SPARTACUS AND THE GREAT ROMAN SLAVE REBELLION europe.factsanddetails.com

Slave Uprising in Sicily Sparked by a Lovesick Roman Knight

Gladiators and Hollywood

Famous films with gladiators include: Gladiator (2000) directed by Ridley Scott with Russell Crowe; Spartacus (1960) directed by Stanley Kubrik with Kirk Douglas as Spartacus. Some historical inaccuracies that appeared in the Hollywood films include Kirk Douglas battle as a gladiator with a trident and net (that event didn't appear until 60 years after Spartacus's time) and Russell Crowe's fight with a gladiator and tiger at the same time (gladiator-versus-gladiator and gladiator-versus-wild-animal contests were separate events).

Commodus, the Roman Emperor

in the film Gladiator Commodus (ruled A.D. 177- 192, co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius from 177-180) was the vainglorious son of Marcus Aurelius who was assassinated in 192, ending the Antonine dynasty. He fancied himself as a great gladiator and battled opponents armed with lead swords that bent when they struck the emperor. Not surprisingly he ran up an impressive string of victories. Commodus finally lost on New Year's Eve, when he was strangled to death by a wrestler who had been dispatched by his rivals.

Commodus was the emperor depicted in the film Gladiator. Edward Gibbons called him a man of “monstrous vices? and “unprovoked cruelty? and wrote: “His hours were spent in a seraglio of three hundred beautiful women, and as many boys, of every rank, and of every province; and whenever the arts of seduction proved ineffectual, the brutal lover had recourse to violence."

Commodus occasionally appeared in the arena during gladiator battles. He never put his life in danger and battled gladiators; instead he liked to decapitate ostriches with crescent-headed arrows. The crowds liked the show. They cheered and roared with laughter as the ostrich continued to run around after their heads were cut off. Once Commodus chopped off the head of an ostrich, and brandished its bloodied head and told senators the same fate awaited them if they went against him. Fearing for their lives, members of Commodus's court decided he had to go. A concubine slipped some poison into his wine and then a wrestler strangled him.

In the movie Gladiator Marcus Aurelius was played by Richard Harris and Commodus was played by Joaquin Phoenix. Contrary to impression given by the movie, Aurelius did no try to restore the republic, he had no general name Maximus (the Russell Crow character) and he was not killing by his son Commodus although the historian Cassius Dio said he was killed by doctors who wanted to “do a favor” for Commodus (most historians believe he died of an illness).

Commodus is believed to have been the only Roman emperor to have taken part in gladiatorial contests. In 2007, archeologists in Rome found a mosaic which they believe depicts a favourite sparring partner of the emperor, named Montanus. The mosaic shows the gladiator holding a trident over a prone opponent who he has apparently defeated in hand-to-hand combat. [Source: Nick Squires, The Telegraph, October 16, 2008]

Film: Gladiator, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Russell Crowe, see History, Marcus Aurelius and Commodus.

Marcus Nonius Macrinus: Inspiration for the Gladiator Film Character

Marcus Nonius Macrinus, a proconsul and a favourite of Marcus Aurelius, who ruled as emperor from 161 A.D. to his death in 180 AD, is believed to be the inspiration for the main character in the film “Gladiator.” Nick Squires wrote in The Telegraph: “ “Macrinus was born in Brescia, in northern Italy, and won victories leading Roman legions into battle. He became a confidant of Emperor Aurelius, being appointed a proconsul in Asia Minor and describing himself as "chosen out of the closest friends". Elements of his life were incorporated into Maximus Decimus Meridius, the fictional character for which Crowe won an Oscar in the 2000 film Gladiator, directed by Ridley Scott. [Source: Nick Squires, The Telegraph, October 16, 2008]

Adrian Murdoch wrote: “What is actually known about Macrinus? Er, not that much. First off, all of it is epigraphic, and the majority comes from ILS 8830, the base of a statue found in 1903 in the agora in Ephesus. It is in Greek and in pretty good condition. It describes him as "consul of Rome, proconsul of Asia, quindecimvir sacris faciundis", and "legate and battlefield companion of Marcus Aurelius". He is also described as consular governor of Pannonia Superior, governor of Pannonia Inferior and commander of Legion XV. The inscription then lists his other honours. [Source: adrianmurdoch.typepad.com]

“Pretty much everything else is a handful of inscriptions found around Brecia. For example:

CIL 05, 04300 which reads: M[arcus] Nonius / Macrinus / ex voto

CIL 05, 04325 which reads: M[arco] Caecilio / Fabia / Privato / amico / M[arcus] Nonius Macrinus / t[estamento] f[ieri] i[ussit]

or CIL 05, 04864: Dis / Conservatorib[us] / pro salute / Arriae suae / M[arcus] Nonius / Macrin[us] consecr[avit]

No mentions of gladiators anywhere.

“In the award-winning film, Maximus is a battle-hardened general and a protégé of the emperor, just as Marcus Nonius Macrinus was....Emperor Marcus Aurelius, played by Richard Harris, is murdered by his ruthless son Commodus, who declares himself emperor and sets about destroying Maximus, ordering the murder of his wife and child. Slave traders take the shattered Maximus to North Africa, where he is sold to a gladiator school and trained as a fighter. Returning to Rome seeking revenge, he eventually kills Commodus in a bloody showdown in the Colosseum, which was famous for its gladiatorial contests.

“The film's scriptwriters also based the character of Maximus on Spartacus, who led a slave revolt against Rome in the 1st century B.C., and Narcissus, a wrestler who brought Commodus' reign as emperor to an abrupt end by strangling him.”

Tomb of Marcus Nonius Macrinus Found and Left to Decay

In 2008, archeologists said they had unearthed the tomb of Marcus Nonius Macrinus — a Roman general thought to have inspired the character played by Russell Crowe in the film 'Gladiator'.Nick Squires wrote in The Telegraph: “The 1,800-year-old stone mausoleum on the banks of the River Tiber was hailed by experts as an "extraordinary discovery" and one of the most important Roman finds for decades. It was built to contain the remains of Marcus Nonius Macrinus’ [Source: Nick Squires, The Telegraph, October 16, 2008]

“The intricately carved marble tomb, complete with a stone inscription identifying it as that of Macrinus, was found near the Via Flaminia, one of the arterial roads which led in and out of ancient Rome. “The jumble of broken columns, friezes and stone blocks was discovered during the demolition of a warehouse, along with remarkably intact parts of the original Roman road.

Tomb of Marcus Nonius Macrinus

“"It's been at least 20 or 30 years since a relic of this importance has come to light in Rome," said a senior archeologist, Daniela Rossi. Over the centuries parts of the tomb crumbled into the Tiber but enough has been recovered during months of painstaking excavation work that experts are discussing the possibility of reconstructing it as the focus of an archeological park.

Tom Kington wrote in The Guardian: “On its discovery in 2008, it was hailed as one of the most significant Roman finds in decades. Digging down between the railway line and mechanics' workshops where the Tiber winds its way north out of Rome, archeologists found the remains of a 45ft high structure fronted by four columns. This was what was left of the luxurious tomb of Marcus Nonius Macrinus...But now cuts mean the tomb may be buried all over again, according to Rome's extremely unhappy state superintendent for archaeology. "I fear we are going to take into serious consideration the idea of protecting these sensational finds by re-covering the entire site with earth," said Mariarosaria Barbera. [Source: Tom Kington, The Guardian, December 9, 2012]

“Today, Macrinus's last resting place – in an industrial wasteland in the suburbs of Rome – appears forgotten. Delicately carved white capitals which were miraculously preserved for 1,800 years under thick clay now sit, discoloured by air pollution, in pools of rainwater, while cracks caused by winter ice have appeared in the stonework.With funding for maintenance of Italy's archeological sites slashed by 20% since 2010 thanks to austerity cuts, the €2m-€3m (£1.6m-£2.4m) needed to preserve the tomb will not be available unless a sponsor is found soon, according to Barbera.”

Amazon and Achillia — Female Gladiators

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic History: Some historical accounts and a handful of surviving stone carvings record the rare appearance of sword-wielding women, a shocking thrill for ancient Romans who thought most women belonged at home. Scholars debate as to whether women actually fought as gladiators or not. A carving found at Halicarnassus, in what is today Turkey, depicts two armed women in gladiator gear. Their stage names, Amazon and Achillia, are accompanied by the result of their fight: a draw. This carving corroborates a handful of ancient accounts of women fighting in the arena. [Source Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

A few ancient authors made clear that women occasionally appeared in the arena, notable because it was so rare. Women fighters were connected with legendary, far-off tribes like the Amazons. “When-ever the audience of an amphithe-ater saw a woman appearing in the arena with arms, and using them skillfully,” writes University of Granada historian Alfonso Manas, “they regarded it as the epitome of exoticism and luxury.” Women fighters were scandalous enough that the emperor Septimius Severus banned them in A.D. 200.

Although the carving of Achillia and Amazon confirms female gladiators competed in the arena, other evidence is more controversial. A little-known bronze statue at the Hamburg Museum of Arts and Crafts depicts a woman naked from the waist up, raising what looks like a curved sword or dagger in her left hand and gazing down, as if at a defeated opponent. Her leg is wrapped in leather or fabric straps known as fasciae, typical gladiator gear. In a 2011 paper, Manas argued the statue represents a female gladiator—only the second known piece of visual evidence for women in the arena. But others say the statue is more likely an athlete, holding aloft a strigil—a scraper Romans used to remove sweat, oil, and dirt. The lack of a helmet and armor suggests she wasn’t a fighter. “No gladiator is depicted with so little protective clothing,” says historian Kathleen Coleman.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston. except bones from Live Science

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024