Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

SCHOOLS FOR GLADIATORS

Training schools for gladiators were called ludi gladiatorii. More than 100 gladiator schools were built throughout the Roman Empire and scholars have found evidence of dozens of them, with the primary known ones being in Rome, Carnuntum, Austria and Pompeii. Gladiators were trained year-round for fights that occurred only a few times a year. A spectator area found at one of Rome facilities suggests gladiator training itself might have attracted an audience, perhaps among gamblers checking out fighters and fans eager to catch a glimpse of their favorite gladiators. and maybe paying money to do so. [Source Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

Ancient Rome's gladiators lived and trained in fortress prisons, according to archaeologists who examined the gladiator school found in Austria described below. “"It was a prison; they were prisoners," Wolfgang Neubauer, an archaeologist at Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology, told National Geographic. "They lived in cells, in a fortress with only one gate out." Gladiators were "big business," Neubauer says. [Source: Dan Vergano, National Geographic, February 25, 2014]

The Ludus Magnus, near Rome’s Colosseum, was a combination barracks and gym for gladiators in training. It had at least four facilities, one with a tunnel leading directly into its lower levels—along with a medical facility, warehouses for sets and props, and a rehab center for wounded fighters. Forceps were among the medical equipment found at Pompeii’s gladiator school. [Source Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: The Gladiator schools were bankrolled by emperors and local dignitaries and often run by trainers called lanistae, some of whom were former gladiators. There were at least four gladiator schools in the center of Rome. The one Carnuntum Austria had a large room with a raised floor that could be heated with warm air from below. It may have been used as a training gym in the cold Austrian winters. Along the edge of an open yard is an L-shaped section of the building with rooms or cells. Thick walls are a sign that parts of the facility had two stories. There were even baths, with water pipes, basins, and hot and cold pools. At the center of it all was a circular training arena, 62 feet across. “We think about 70 or 75 gladiators lived here,” archaeologist Eduard Pollhammer says. “There’s a whole infrastructure for big spectacles.” [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, July 20, 2021]

RELATED ARTICLES:

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

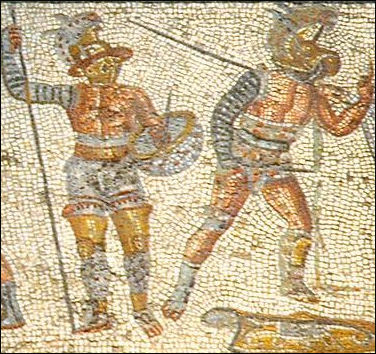

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: THEIR LIVES, DIETS, HOMES AND GLORY europe.factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS GLADIATORS europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: HISTORY, IMPORTANCE AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

Film “Gladiator”, with Russel Crowe, directed by Ridley Scott (2000) DVD Amazon.com;

“The Way of the Gladiator: Inspiration for the Gladiator Films” by Daniel P. Mannix (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Real Gladiator: The True Story of Maximus Decimus Meridius” by Tony Sullivan (2022) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: 100 BC–AD 200" by Stephen Wisdom, Angus McBride (Illustrator) (2001) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators 1st–5th centuries AD” by François Gilbert, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator), (2024) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: Deadly Arena Sports of Ancient Rome” by Christopher Epplett (2017) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Roman World” by Sandra R. Joshel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Society at Rome” by Keith Bradley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” by Howard Fast (1951) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” DVD with Kirk Douglas as Spartacus, Laurence Olivier, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1960) Amazon.com;

“The Spartacus War” by Barry S. Strauss (2009) Amazon.com

How the Gladiator Schools Operated

Tolga İldun wrote in Archaeology magazine: Behind a day in the arena was a well-organized professional system. “We know that there were schools where gladiators were coached by experienced trainers and that they were well fed and received medical care,” archaeologist Martin Steskal told Archaeology magazine. Sources indicate that gladiator schools even had specialized doctors on call. The physician Galen, who lived in the Anatolian city of Pergamon in the mid-second century A.D., writes that no gladiators died over a five-year period when he provided them with medical care. “Galen likely learned about medicine from, among others, his predecessor, the Ephesian physician Rufus,” says Steskal. “The last thing a school owner wanted was for his gladiator to die. If a gladiator died in his first fight, it would mean all that investment was wasted.” [Source Tolga İldun, Archaeology magazine, November-December, 2024 archaeology.org]

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic History: Gladiator barracks were expensive to run, and many belonged to the emperor or rich Romans. Managed by impresarios called lanistae, typically ex-gladiators who had won their freedom in combat, the barracks employed a range of specialists. Staff included doc-tors charged with giving fighters the best medical care, unctores, or “ointment men,” responsible for oiling and massaging gladiators after workouts, and a complement of cooks, armorers, and other staff. [Source Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

.jpg) Cicero speaks of one gladiator school at Rome during his consulship, and there were others before his time at Capua and Praeneste. Some of these were set up by wealthy nobles for the purpose of preparing their own gladiators for gladiator contests which they expected to give; others were the property of regular dealers in gladiators, who kept and trained them for hire. The business was at first almost as disreputable as that of the lenones. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Cicero speaks of one gladiator school at Rome during his consulship, and there were others before his time at Capua and Praeneste. Some of these were set up by wealthy nobles for the purpose of preparing their own gladiators for gladiator contests which they expected to give; others were the property of regular dealers in gladiators, who kept and trained them for hire. The business was at first almost as disreputable as that of the lenones. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

During the Empire, however, training schools were maintained at public expense and under the direction of state officials, not only in Rome, where there were four at least of these schools, but also in other cities of Italy, where exhibitions were frequently given, and even in the provinces. The purpose of all the schools, public and private alike, was the same, to make the men trained in them as effective fighting machines as possible. The gladiators were in charge of competent training masters (lanistae); they were subject to the strictest discipline; their diet was carefully looked after, and a special food (sagina gladiatoria) was provided for them; regular gymnastic exercises were prescribed, and lessons in the use of the various weapons were given by recognized experts (magistri, doctores). In their fencing bouts, wooden swords (rudes) were used. The gladiators associated in a school were collectively called a familia. |+|

Parts of Gladiator Schools

Gladiator schools had also to serve as barracks for the gladiators between engagements, that is, practically as houses of detention. It was from the school of Lentulus at Capua that Spartacus had escaped, and the Romans needed no second lesson of the sort. The general arrangement of these barracks may be understood from the ruins of one uncovered at Pompeii, though in this case the buildings had been originally planned for another purpose, and the rearrangement may not be typical in all respects. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“A central court, or exercise ground, is surrounded by a wide colonnade, and this in turn by rows of buildings two stories in height; the general arrangement is not unlike that of the peristyle of a house. The dimensions of the court are nearly 120 by 150 feet. The buildings are cut up into rooms, nearly all small (about twelve feet square), disconnected and opening upon the court; those in the first story are reached from the colonnade, those in the second from a gallery to which ran several stairways. These small rooms are supposed to be the sleeping rooms of the gladiators; each accommodated two persons. There are seventy-one of them (marked 7 on the plan), affording room for one hundred forty-two men. The uses of the larger rooms are purely conjectural.

“The entrance is supposed to have been at 3, with a room (15) for the watchman or sentinel. At 9 was an exedra, where the gladiators may have waited in full panoply for their turns in the exercise ground (1). The guard room (8) is identified by the remains of stocks, in which the refractory were fastened for punishment or safekeeping. The stocks permitted the culprits to lie only on their backs or to sit in a very uncomfortable position. At 6 was the armory or property room, if we may judge from articles found in it. Near it in the corner was a staircase leading to the gallery before the rooms of the second story. The large room (16) was the mess-room, with the kitchen (12) opening into it. The stairway (13) gave access to the rooms above kitchen and mess-room, possibly the apartments of the trainers and their helpers.” |+|

Ludus Magnus: Gladiator Training Ground in Rome

“The cells of the gladiators on the northern side of the building have been excavated and are visible. This part was connected to the Via Labicana by a monumental entrance. The Greek-Roman historian Herodian states that the emperor-gladiator Commodus (r.180-192) used to sleep in one of these cells.

“There were three other wings of cells and the building seems to have had at least two storeys. All in all, there must have been about 130 cells. In the four corners between the arena and the surrounding porticoes, where the cells were, were water basins. The arena, which has been partially excavated, was surrounded by seats for the public, including a VIP box. It seems that people liked to watch the exercising gladiators, because there were no less than 3,000 seats. The Ludus Magnus was restored by the emperor Trajan (r.98-117).”

Roman Gladiator School Found in Austria

In 2011 it was revealed that some well-preserved ruins of a Roman gladiator school had been found in Carnuntum near Petronell-Varnuntum, Austria. The Carnuntum ruins are part of a city of 50,000 people 45 kilometers east of Vienna that flourished about 1700 years ago. It was a major military and trade outpost linking the far-flung Roman empire's Asian boundaries to its central and northern European lands. It was a key link in the European amber trade. [Source: George Jahn, Associated Press, September 6, 2011]

Dan Vergano of National Geographic wrote: “At least 80 gladiators, likely more, lived in the large, two-story facility equipped with a practice arena in its central courtyard. The site also included heated floors for winter training, baths, infirmaries, plumbing, and a nearby graveyard. Within the 118,400-square-foot (11,000-square-meter) walled compound at the Austrian site, gladiators trained year-round for combat at a nearby public amphitheater [Source: Dan Vergano, National Geographic, February 25, 2014]

Mapped out by radar, the ruins of the gladiator school remain underground. Yet officials say the find rivals the famous Ludus Magnus - the largest of the gladiatorial training schools in Rome - in its structure. And they say the Austrian site is even more detailed than the well-known Roman ruin, down to the remains of a thick wooden post in the middle of the training area, a mock enemy that young, desperate gladiators hacked away at centuries ago.

The gladiator complex is part of a 10 square km site over the former city, an archaeological site now visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists a year. This is “a world sensation, in the true meaning of the word," Lower Austrian provincial governor Erwin Proell told Associated Press. The Carnuntum ruins, he said, were "unique in the world ... in their completeness and dimension". Officials said they had no date yet for the start of excavations of the gladiator school, saying experts needed time to settle on a plan that conserves as much as possible.

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine“ Radar scans showed that, like the Ludus Magnus, the Carnuntum complex had two levels of colonnaded galleries that enclosed a courtyard. The central feature inside the courtyard was a free-standing circular structure, which the researchers interpreted as a training arena that would have been surrounded by wooden spectator stands set on stone foundations. Within the arena was a walled ring that may have held wild beasts. Galleries along the southern and western wings not designated as infirmaries, armories or administrative offices would have been set aside for barracks. Neubauer figures that about 75 gladiators could have lodged at the school. “Uncomfortably,” he says. The tiny (32-square-foot) sleeping cells were barely big enough to hold a man and his dreams, much less a bunkmate. “Neubauer deduced that other rooms — more spacious and perhaps with tiled floors — were living quarters for high-ranking gladiators, instructors or the school’s owner (lanista). A sunken cell, not far from the main entrance, seems to have been a brig for unruly fighters. The cramped chamber had no access to daylight and a ceiling so low that standing was impossible. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2016]

Facilities at the Austrian Gladiator School

Thick walls surround 11,000 square metres of the site, and the school and its adjacent buildings stretch over 2800 square metres. Inside, a courtyard was ringed by living quarters and other buildings and contained a round, 19 square meter training area, a small stadium overlooked by wooden seats and the terrace of the chief trainer.

The complex also contained about 40 tiny sleeping cells for the gladiators; a large bathing area; a training hall with heated floors and assorted administrative buildings. The cells, where the gladiators lived, were barely big enough to turn around in Outside the walls, radar scans show what archeologists believe was a cemetery for those killed during training.

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “The school’s northern wing, the bathhouse, was centrally heated. During cold European winters — temperatures could fall to minus-13 degrees — the building was warmed by funneling heat from a wood-burning furnace through gaps in the floor and walls and then out roof openings. Archaeologists detected a chamber that they believe may have been a training room: they were able to see a hollow space, or hypocaust, under the floor, where heat was conducted to warm the paving stones underfoot. The bathhouse, with its thermal pools, was fitted with plumbing that conveyed hot and cold water. Looking at the bath complex, Neubauer says, “confirmed for the first time that gladiators could recover from harsh, demanding training in a fully equipped Roman bath.” [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2016]

According to National Geographic: The bath complex was made of four interconnected rooms, which helped gladiators recover from their rigorous training. There was a Frigidarium (cold bath) Caldarium (hot bath), Tepidarium (warm room), storage room, Apodyterium (changing room) and assembly hall. The large training room may have served as a multi-purpose gathering space with long tables and chairs. A hypocaust — the Roman system for under-floor heating — would have allowed training to continue in the winter months. Two wings of the school held rooms of varying size and ornamentation that housed up to 75 gladiators and trainers. The owner, or lanista, lived and worked in the buildings at the school’s entrance. He had the power of life and death over the gladiators, who had no rights under Roman law. Viewing stands enclosed an arena where instruction and practice could be seen by a fighter’s owner and potential investors. [Source: Fernando G. Baptista, National Geographic, July 20, 2021]

Life at the Austrian Gladiator School

A gladiator school was a mixture of a barracks and a prison, kind of a high-security facility," said the Roemisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, one of the institutes involved in finding and evaluating the Austrian gladaitor school: "The fighters were often convicted criminals, prisoners-of-war, and usually slaves." [Source: George Jahn, AP, September 6, 2011]

Dan Vergano of National Geographic wrote: “The gladiators slept in 32-square-foot (3-square-meter) cells, home to one or two people. Those cells were kept separate from a wing holding bigger rooms for their trainers, known as magistri, themselves retired survivors of gladiatorial combat who specialized in teaching one style of weaponry and fighting. "The similarities show that gladiators were housed and trained in the provinces in the same way as in the metropolis [of Rome]," Coleman says. The one gate exiting the compound faced a road leading to the town's public amphitheater, reportedly the fourth largest in the empire. The fortress prison also undermines the image of gladiators as traveling from town to town in a circus-like setting, as seen in the movie Gladiator released in 2000. "They weren't a team," Neubauer says. "Each one was on his own, training to fight, and learning who they would combat at a central post we can see the remains of in our survey." [Source: Dan Vergano, National Geographic, February 25, 2014]

George Jahn of AP wrote: “Still, there were some perks for the men who sweated and bled for what they hoped would at least be a few brief moments of glory before their demise.At the end of a dusty and bruising day, they could pamper their bodies in baths with hot, cold and lukewarm water. And hearty meals of meat, grains and cereals were plentiful for the men who burned thousands of calories in battle each day for the entertainment of others. The institute said the training area was where the men's "market value and in end effect their fate" was decided. At the same time, it gave them a small chance for survival, fame and possibly liberty. "If they were successful, they had a chance to advance to 'superstar' status - and maybe even achieve freedom," said Carnuntum park head Franz Humer.

New arrivals, or novicus, were assigned a specialty and trained with double-weight wooden swords and shields against wooden posts. Protecting their investments, owners limited gladiators to a few fights each year. Fighting style and skill level determined arena pairings. Gladiators were kept healthy with regular medical care and a diet high in barley and beans. Some were married and had families. Injuries were common, but most weren’t lethal. Even so, many gladiators died young. Only skilled or especially lucky fighters had long careers.

Gladiator Training at the Austrian Gladiator School

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine; “Neubauer likens the school in Carnuntum to a penitentiary. Under the Republic (509 B.C. to 27 B.C.), the “students” tended to be convicted criminals, prisoners of war or slaves bought solely for the purpose of gladiatorial combat by the lanista, who trained them to fight and then rented them out for shows — if they had the right qualities. Their ranks also included free men who volunteered as gladiators. Under the Empire (27 B.C. to A.D. 476), gladiators, while still made up of social outcasts, also included not only free men, but noblemen and even women who willingly risked their legal and social standing by taking part in the sport. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2016]

It’s doubtful that many fighters-in-training were killed at Carnuntum’s school. The gladiators represented a substantial investment for the lanista, who trained, housed and fed combatants, and then leased them out. Contrary to Hollywood mythmaking, slaying half the participants in any given match wouldn’t have been cost-effective. Ancient fight records suggest that while amateurs almost always died in the ring or were so badly maimed that waiting executioners finished them off with one merciful blow, around 90 percent of trained gladiators survived their fights.

“The mock arena at the heart of the Carnuntum school was ringed by tiers of wooden seats and the terrace of the chief lanista. (A replica was recently built on the site of the original, an exercise in reconstruction archaeology deliberately limited to the use of tools and raw materials known to have existed during the Empire years.) In 2011, GPR detected the hole in the middle of the practice ring that secured a palus, the wooden post that recruits hacked at hour after hour. Until now it had been assumed that the palus was a thick log. But LBI ArchPro’s most recent survey indicated that the cavity at Carnuntum was only a few inches thick. “A thin post would not have been meant just for strength and stamina,” Neubauer argues. “Precision and technical finesse were equally important. To injure or kill an opponent, a gladiator had to land very accurate blows.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston. except bones from Live Science

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024