Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES

In Roman times, spectators gathered in the Colosseum to watch gladiators battle each other to the death and unarmed men duel starved lions. In the latter the odds were tipped in favor of the lions, which were more difficult to replace than people. The wooden floor of the Colosseum was covered with sand so the combatants wouldn't slip on the blood. Contrary to the popular misconception almost all of the men who perished in the bloody battles were pagan slaves not Christians.

In Roman times, spectators gathered in the Colosseum to watch gladiators battle each other to the death and unarmed men duel starved lions. In the latter the odds were tipped in favor of the lions, which were more difficult to replace than people. The wooden floor of the Colosseum was covered with sand so the combatants wouldn't slip on the blood. Contrary to the popular misconception almost all of the men who perished in the bloody battles were pagan slaves not Christians.

Sometimes the floor of the Colosseum was filled with wild animals for staged hunts or was flooded for mock sea battles complete with galleys and navies. One grand 100-day celebration in A.D. 2nd century left 5,000 wild animals dead. When Rome became christianized around the A.D. 5th century bloody spectacles were banned and replaced with church dramas and passion plays.

Some scholars have said that descriptions of a flooded Colosseum for these mock battles were exaggerations because no evidence of large waterworks capable of bringing enough water to stage such events had been discovered. Then in 2003, archeologists and spelunkers found that below the simple drains used to drain off rain water that predated the Colosseum were large conduits constructed by Emperor Nero to change the water in the artificial lake in his gardens. The conduits bore signs of having been originally used at the Colosseum, perhaps to pipe large quantities of water in and out for water spectacle like mock naval battles.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: HISTORY, IMPORTANCE AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: LAYOUT, ARCHITECTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

PUBLIC GAMES AND SHOWS OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS europe.factsanddetails.com

NAUMACHIAE — GIANT ROMAN STAGED SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN SPORT: BALL GAMES AND FIXED WRESTLING MATCHES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECREATION IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Colosseum: Design - Construction - Events” by Nigel Rodgers (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Colosseum” edited by Ada Gabucci (Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 2001)

Amazon.com;

“The Roman Amphitheatre: From its Origins to the Colosseum” by Katherine E. Welch (2007) Amazon.com

“The Roman Games: A Sourcebook (Blackwell) by Alison Futrell Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Spectacle in the Roman World” by Hazel Dodge (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Day Commodus Killed a Rhino: Understanding the Roman Games” (Witness to Ancient History) by Jerry Toner (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Sourcebook” by Anne Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide” by Paul Plass (1995) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Way of the Gladiator: Inspiration for the Gladiator Films” by Daniel P. Mannix (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Real Gladiator: The True Story of Maximus Decimus Meridius” by Tony Sullivan (2022) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: 100 BC–AD 200" by Stephen Wisdom, Angus McBride (Illustrator) (2001) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators 1st–5th centuries AD” by François Gilbert, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator), (2024) Amazon.com;

Spectator Experience at the Colosseum

Keith Hopkins of the University of Cambridge wrote for the BBC: “Spectators found their way to their seats through arches numbered I - LXXVI (1-76). The four grand entrances were not numbered. The best seats were on or just behind the podium, raised for safety's sake two metres above the arena; animals and gladiators were kept out by a further fence just inside the arena, which helped to ensure that the action was in everybody's view. [Source: Keith Hopkins, BBC, March 22, 2011 |::|]

“Inside the amphitheatre, but at its outer rim, there were, at the first three levels, grand circular promenades, though as you went upwards the dimensions became smaller and the decoration less grand. At the first level, the floors were of marble or Travertine (the stone from which the outside walls were made), while the walls were of polished marble slabs and the ceilings of painted stucco. Their present grim decoration does not do them justice - and the exterior, pockmarked with holes made by medieval robbers looking for iron clamps, gives no real indication, either, of what the building looked like in antiquity. |::|

“Inside the auditorium, except for the front rows on the podium, spectators were packed like sardines in a tin. Evidence from other amphitheatres suggests an average of 40 centimeters width per spectator and 70 centimeters legroom, which makes an economy class airline seem generous. The entrances and staircase were arranged with the help of marble and iron dividers - to keep different classes of clientele separate. Indeed, the very top section of the Colosseum is separated from other spectators by a 5m- (16ft-) high wall. |::|

“Modern scholars often say that the hierarchy of seating mirrored the social hierarchies of Roman society. But we should be cautious. The five sections of the auditorium, from bottom to top, would have contained only about 50,000 predominantly adult males out of an adult male population in the city of Rome of close on 300,000. The lower class population of Rome was seriously and systematically under-represented. And the two lowest (ie most prestigious) sections of the auditorium accommodated, respectively over 2,000 and almost 12,000 spectators, numbers which do not coincide with any known social groups, such as senators (600) or knights (perhaps 5,000). Those in the top rows had shade, while nobles sweated in the sun; but those at the very top, which would have included women and the poor, were a good 100m from the centre of the arena. The myopic presumably just sat and heard the crowd roar.” |::|

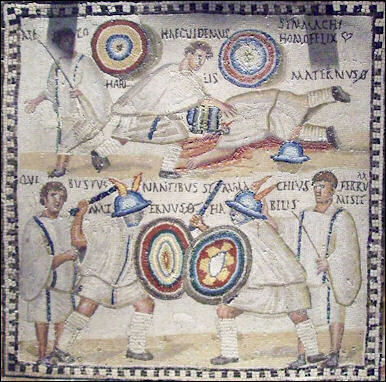

Gladiator Fights at the Colosseum

Crowds 45,000-strong showed up to watch gladiator battles at the Coliseum. An event hosted by Caesar contained 320 separate contests. Some bloody spectacles lasted for months.One bloody circus during Titus's rule lasted for 123 straight days and between 5,000 people and 11,000 were killed. Under Augustus eight large gladiator events were held, each with around 1,250 gladiators.

On large shows at the Colosseum: “Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Following the executions came the main event: the gladiators. While attendants prepared the ritual whips, fire and rods to punish poor or unwilling fighters, the combatants warmed up until the editor gave the signal for the actual battle to begin. Some gladiators belonged to specific classes, each with its own equipment, fighting style and traditional opponents. For example, the retiarius (or “net man”) with his heavy net, trident and dagger often fought against a secutor (“follower”) wielding a sword and wearing a helmet with a face mask that left only his eyes exposed.

“Contestants adhered to rules enforced by a referee; if a warrior conceded defeat, typically by raising his left index finger, his fate was decided by the editor, with the vociferous help of the crowd, who shouted “Missus!” (“Dismissal!”) at those who had fought bravely, and “Iugula, verbera, ure!” (“Slit his throat, beat, burn!”) at those they thought deserved death. Gladiators who received a literal thumbs down were expected to take a finishing blow from their opponents unflinchingly. The winning gladiator collected prizes that might include a palm of victory, cash and a crown for special valor. Because the emperor himself was often the host of the games, everything had to run smoothly. The Roman historian and biographer Suetonius wrote that if technicians botched a spectacle, the emperor Claudius might send them into the arena: “[He] would for trivial and hasty reasons match others, even of the carpenters, the assistants and men of that class, if any automatic device or pageant, or anything else of the kind, had not worked well." Or, as Heinz-Jürgen Beste of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome puts it, “The emperor threw this big party, and wanted the catering to go smoothly. If it did not, the caterers sometimes had to pay the price." [Source: Tom Mueller, Smithsonian magazine, January 2011]

“To spectators, the stadium was a microcosm of the empire, and its games a re-enactment of their foundation myths. The killed wild animals symbolized how Rome had conquered wild, far-flung lands and subjugated Nature itself. The executions dramatized the remorseless force of justice that annihilated enemies of the state. The gladiator embodied the cardinal Roman quality of virtus, or manliness, whether as victor or as vanquished awaiting the deathblow with Stoic dignity. “We know that it was horrible," says Mary Beard, a classical historian at University of Cambridge, “but at the same time people were watching myth re-enacted in a way that was vivid, in your face and terribly affecting. This was theater, cinema, illusion and reality, all bound into one."”

Proper and Legitimate Gladiator Show at the Colosseum

Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The official spectacle, known as the munus iustum atque legitimum (“a proper and legitimate gladiator show”) at the Colossuem, began, like many public events in Classical Rome, with a splendid morning procession, the pompa. It was led by the editor's standard-bearers and typically featured trumpeters, performers, fighters, priests, nobles and carriages bearing effigies of the gods. (Disappointingly, gladiators appear not to have addressed the emperor with the legendary phrase, “We who are about to die salute you," which is mentioned in conjunction with only one spectacle — a naval battle held on a lake east of Rome in A.D. 52 — and was probably a bit of inspired improvisation rather than a standard address.) [Source: Tom Mueller, Smithsonian magazine, January 2011]

“The first major phase of the games was the venatio, or wild beast hunt, which occupied most of the morning: creatures from across the empire appeared in the arena, sometimes as part of a bloodless parade, more often to be slaughtered. They might be pitted against each other in savage fights or dispatched by venatores (highly trained hunters) wearing light body armor and carrying long spears. Literary and epigraphic accounts of these spectacles dwell on the exotic menagerie involved, including African herbivores such as elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses and giraffes, bears and elk from the northern forests, as well as strange creatures like onagers, ostriches and cranes. Most popular of all were the leopards, lions and tigers — the dentatae (toothed ones) or bestiae africanae (African beasts) — whose leaping abilities necessitated that spectators be shielded by barriers, some apparently fitted with ivory rollers to prevent agitated cats from climbing. The number of animals displayed and butchered in an upscale venatio is astonishing: during the series of games held to inaugurate the Colosseum, in A.D. 80, the emperor Titus offered up 9,000 animals. Less than 30 years later, during the games in which the emperor Trajan celebrated his conquest of the Dacians (the ancestors of the Romanians), some 11,000 animals were slaughtered.

“The hypogeum played a vital role in these staged hunts, allowing animals and hunters to enter the arena in countless ways. Eyewitnesses describe how animals appeared suddenly from below, as if by magic, sometimes apparently launched high into the air. “The hypogeum allowed the organizers of the games to create surprises and build suspense," Beste says. “A hunter in the arena wouldn't know where the next lion would appear, or whether two or three lions might emerge instead of just one." This uncertainty could be exploited for comic effect. Emperor Gallienus punished a merchant who had swindled the empress, selling her glass jewels instead of authentic ones, by setting him in the arena to face a ferocious lion. When the cage opened, however, a chicken walked out, to the delight of the crowd. Gallienus then told the herald to proclaim: “He practiced deceit and then had it practiced on him." The emperor let the jeweler go home.”

Intermissions and Executions at the Colosseum Shows

Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “During the intermezzos between hunts, spectators were treated to a range of sensory delights. Handsome stewards passed through the crowd carrying trays of cakes, pastries, dates and other sweetmeats, and generous cups of wine. Snacks also fell from the sky as abundantly as hail, one observer noted, along with wooden balls containing tokens for prizes — food, money or even the title to an apartment — which sometimes set off violent scuffles among spectators struggling to grab them. On hot days, the audience might enjoy sparsiones (“prinklings”), mist scented with balsam or saffron, or the shade of the vela, an enormous cloth awning drawn over the Colosseum roof by sailors from the Roman naval headquarters at Misenum, near Naples. [Source: Tom Mueller, Smithsonian magazine, January 2011]

“At the ludi meridiani, or midday games, criminals, barbarians, prisoners of war and other unfortunates, called damnati, or “condemned," were executed. (Despite numerous accounts of saints’ lives written in the Renaissance and later, there is no reliable evidence that Christians were killed in the Colosseum for their faith.) Some damnati were released in the arena to be slaughtered by fierce animals such as lions, and some were forced to fight one another with swords. Others were dispatched in what a modern scholar has called “fatal charades," executions staged to resemble scenes from mythology. The Roman poet Martial, who attended the inaugural games, describes a criminal dressed as Orpheus playing a lyre amid wild animals; a bear ripped him apart. Another suffered the fate of Hercules, who burned to death before becoming a god.

“Here, too, the hypogeum's powerful lifts, hidden ramps and other mechanisms were critical to the illusion-making. “Rocks have crept along," Martial wrote, “and, marvelous sight! A wood, such as the grove of the Hesperides [nymphs who guarded the mythical golden apples] is believed to have been, has run."”

Violent Spectacles

In a review of the book: The Colosseum by Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard, Nigel Spivey wrote The Guardian, “Archaeological evidence shows that some athletic stadia were converted for use as amphitheatres, and a number of Greek theatres were adapted - high nets rigged around the stage, for instance, to prevent big cats leaping into the audience. Yet there are records of strident Greek protests, if only on behalf of those front-row onlookers who did not care to be sprayed with blood. And this categorical distinction between theatre and amphitheatre points us to the principal fascination of approaching the Roman Colosseum as a "wonder of the world": the wonder lies not with the elegance or substance of the building as it survives, but rather with the question of what the Romans thought they were doing. [Source: Nigel Spivey, The Guardian, March 12, 2005 ^^]

“As Keith Hopkins has pointed out before, Roman enjoyment of spectacular violence is not a matter of "individual sadistic psychopathology", but seems to betray "a deep cultural difference". How much Hopkins contributed to the present book before he died last year is not easy to estimate, because Mary Beard (a Cambridge colleague) has so sympathetically overlaid it with her own voice. But it was characteristic of Hopkins to begin answering the puzzle of a peculiar Roman "taste" for violence by sceptically probing its extent.^^

“Quite how this ingenious mode of human sacrifice originated is left implicit by Hopkins and Beard. They dismiss without reason the notion that gladiatorial combat developed out of archaic Etruscan funerary rites, and offer no plausible alternative. So what was the Colosseum all about? The applications of capital punishment within the amphitheatre were conducted at midday, as a lull in proceedings, deemed a diversion only for the chronically bored. So connoisseurs of bloodshed came for more than the sight of exemplary justice. Protagonists of good entertainment were marked not by damnation but chance; made brave or furious by freedom from blame, how much more fiercely they would fight. ^^

“Some ancient observers - notably St Augustine - deplored the addictive magnetism of witnessing this sort of death. Others were complacent about its habituating and homeopathic effect: so death was, as it were, domesticated. But in the end it is impossible to explain the Colosseum unless one concedes that its principal sponsors - the emperors of Rome - all of them, even "good" ones such as Trajan, ultimately ruled by terror. This arena by the Palatine, the hill on which Romulus founded his city, was the looming and central emblem of their power to "play God" - to allocate life or death.” ^^

Violent Spectacles at the Colosseum: How Accurate Where the Reports

Gordon Gora wrote in Listverse: “Starting with the infamous Caligula and the later famed bestiarii Carpophorus, the gladiator games became an excuse to showcase the brutality of man and the world. The bestiarii’s job was to train animals for the shows such as training an eagle to eat the exposed organs of a thrashing fighter. Carpophorus was the most famous bestiarii of all and not only trained his beasts to kill the poor souls in the colosseum in the most graphic manner possible but fought many of them himself. The most shocking act Carpophorus trained his animals to do, however, was rape human prisoners on command for the shock and awe of those in the Colosseum. [Source: Gordon Gora Listverse, September 16, 2016]

Nigel Spivey wrote The Guardian, “The inauguration of the Colosseum was allegedly celebrated by hunting shows involving the deaths of 9,000 exotic animals. But how feasible was it to capture elephants and rhinoceroses without sedative darts, transport them long distances, and finally cajole them to ferocity in front of a large crowd? Documentary evidence of the laborious zoological kidnap of a single hippotamus from the Upper Nile to Regent's Park in 1850 suggests that supplying the Colosseum with large quantities of interesting animals was a logistical challenge beyond even the Romans. Further and more complex calculations about gladiatorial death-rates similarly indicate a strong tendency to exaggerate, and not only by ancient writers. Christian martyrologists piously inflated the number of casualties among the faithful. (In an unsually candid reflection, one persecuted Christian witness, Origen, wondered if the total tally of Christian martyrs at Rome actually reached double figures.) There is, in fact, no firm evidence to prove that any Christian was ever torn apart by lions inside the Colosseum. [Source: Nigel Spivey, The Guardian, March 12, 2005 ^^]

“Another type of spectacle that took place was the public execution. Condemned criminals were slain by crucifixion, cremation, or attack by wild beasts, and were sometimes forced to reenact gruesome myths. “Even when stripped of its mythology, the amphitheatre subsists as an enclosure designed to give a maximum number of onlookers the closest possible view of a kill. Academic demonstrations of human anatomy used to be compassed in such steep-sided, eye-goggling spaces. The old bullring of Mexico City relies, to this day, on the same telescopic principle. We may agree that the daily pabulum of the Roman populace was bread, not circuses. Still the circus existed all the same; and no one went there for some harmless fun. The closest to slapstick at the Colosseum came from the so-called "fatal charades", when some myth was enacted for real: the flight of Icarus, done like a bungee jump without the bungee; or else a wretched criminal dressed up as Orpheus -given a lyre, and pushed out to charm with melodies the animals prowling around the arena. Too bad if the bears were tone deaf.” ^^

Book: “The Colosseum” by Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard (Profile, 2005)

Colosseum Naumachiae

Alexander Larman wrote in The Telegraph: Nothing compared to the elaborate nature of the festivities staged for the construction of the Colosseum in B.C. 80, at the command of the emperor Titus. It proved to be an astonishingly difficult feat of engineering to flood the newly-built Colosseum, an activity that was estimated to take anything between 17 days and a month, and required the construction of an aqueduct that would connect the Tiber to the arena, filling it up to precisely the depth that would allow the extravaganza to take place, and then letting all hell break loose. [Source Alexander Larman, The Telegraph, July 10, 2024]

The historian Cassius Dio describes the spectacle that ensued economically. “Titus suddenly filled this same theater with water and brought in horses and bulls and some other domesticated animals that had been taught to behave in the liquid element just as on land. He also brought in people on ships, who engaged in a sea-fight there, impersonating the Corcyreans and Corinthians.”

The recreation of the historic battle, including the creation of an artificial island, may have been popular as an idea, but the execution was stymied by the appearance of a violent rainstorm that not only led to the deaths of all the surviving combatants through drowning, but killed many of the spectators as well.

Thereafter, the extraordinary expense and effort that went into such elaborate plans were dispensed with. Audiences seemed perfectly happy with land-bound gladiatorial spectacle instead, especially if some wild and exotic animals might be recruited for the fighting, too. The Colosseum therefore had subterranean tunnels and cells built beneath it that could house both human fighters and creatures alike, which meant that flooding the space would be impossible.

See Separate Article: NAUMACHIAE — GIANT ROMAN STAGED SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com

Colosseum Snacks and Bones of Dead Beasts

According to Archaeology magazine: An investigation of the sewer system that collected refuse and debris washed down from above indicates that fans munched on olives, figs, walnuts, and melons. They even enjoyed freshly cooked meat prepared on improvised braziers. Skeletal remains of beasts that died fighting for the Romans’ entertainment, such as tigers, bears, and leopards, were also found.[Source: Archaeology magazine, March 2023]

A year-long study of the drainage system under the Colosseum in the early 2020s revealed evidence of snack foods as wells fragments of the bones of bears and big cats that were probably used to fight or as prey in hunting games. Reuters reported: Seeds from fruits such as figs, grapes and melons as well as traces of olives and nuts — thought to indicate what spectators snacked on during shows — were also recovered from the 2,000-year-old stone amphitheater. [Source: Reuters, November 25, 2022]

The study, which began in January, involved the clearance of around 70 meters of drains and sewers under the Colosseum and is seen as shedding light on its later years before it fell into disuse around 523 AD. Alfonsina Russo, Director of the Colosseum Archaeological Park, said the discoveries "deepen our understanding of the experience and habits of those who came to this place during the long days dedicated to the performances".

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024