Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

TYPES OF GLADIATORS

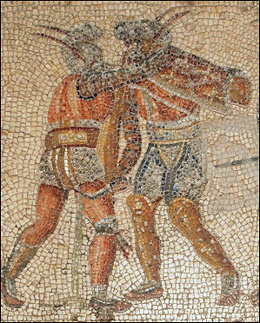

A variety of gladiator contests were staged during the time of the Roman Empire. The combatants fought in specific categories, each with certain rules, weapons and armor. There were several different types of gladiators with their own specialty type of fighting, known as their armatura. Generally, they wore different kinds of armor and used different kinds of weapons. Retiarii carried a net and Neptune-like trident and lithely danced around the arena. Murmillones were the equivalent of heavyweight boxers. They carried heavy swords and shields. Samnites carried a large oblong shield, a sword or spear, and were protected by visored helmets, greaves on their right leg and a protective sleeve on the right arm.

Gladiators usually fought in pairs, man against man, but sometimes in masses (gregatim, catervatim). In early times they were actually soldiers, captives taken in war , and so naturally fought with the weapons and equipment to which they were accustomed. When the professionally trained gladiators came in, they received the old names, and were called “Samnites,” “Thracians,” etc., according to their arms and tactics. In much later times victories over distant peoples were celebrated with combats in which the weapons and methods of war of the conquered were shown to the people of Rome; thus, after the conquest of Britain essedarii exhibited in the arena the tactics of chariot fighting which Caesar had described several generations before in his Commentaries. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“It was natural enough, too, for the people to want to see different arms and different tactics tried against one another, and so the Samnite was matched against the Thracian, the heavy-armed against the light-armed. This became under the Empire the favorite style of combat. Finally, when people had tired of the regular shows, novelties were introduced that seem to us grotesque; men fought blindfold (andabatae), or armed with two swords (dimachaeri), or with the lasso (laqueatores), or with a heavy net (retiarii). There were also battles of dwarfs and of dwarfs with women. Of these the retiarius became immensely popular. He carried a huge net in which he tried to entangle his opponent, always a secutor, dispatching him with a dagger if the throw was successful. If unsuccessful he took to flight while preparing his net for another throw; or if he had lost his net, he tried to keep his opponent off with a heavy three-pronged spear (fuscina), his only weapon besides the dagger. |+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: THEIR LIVES, DIETS, HOMES AND GLORY europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR SCHOOLS AND TRAINING europe.factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS GLADIATORS europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: HISTORY, IMPORTANCE AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: LAYOUT, ARCHITECTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007); Meijer is a professor of ancient history at the University of Amsterdam. The book is interesting and is good at anticipating questions readers have and providing satisfactory answers on topics like the events and weapons in the contests and how the gladiators were paid and fed. Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

Film “Gladiator”, with Russel Crowe, directed by Ridley Scott (2000) DVD Amazon.com;

“The Way of the Gladiator: Inspiration for the Gladiator Films” by Daniel P. Mannix (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Real Gladiator: The True Story of Maximus Decimus Meridius” by Tony Sullivan (2022) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: 100 BC–AD 200" by Stephen Wisdom, Angus McBride (Illustrator) (2001) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators 1st–5th centuries AD” by François Gilbert, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator), (2024) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: Deadly Arena Sports of Ancient Rome” by Christopher Epplett (2017) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiator: The Secret History Of Rome's Warrior Slaves” by Alan Baker Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Roman World” by Sandra R. Joshel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Society at Rome” by Keith Bradley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” by Howard Fast (1951) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” DVD with Kirk Douglas as Spartacus, Laurence Olivier, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1960) Amazon.com;

“The Spartacus War” by Barry S. Strauss (2009) Amazon.com

Styles of Gladiator Fighting

Gladiators fought usually in pairs, man against man, but sometimes in masses (gregatim, catervatim). In early times they were actually soldiers, captives taken in war , and so naturally fought with the weapons and equipment to which they were accustomed. When the professionally trained gladiators came in, they received the old names, and were called “Samnites,” “Thracians,” etc., according to their arms and tactics. In much later times victories over distant peoples were celebrated with combats in which the weapons and methods of war of the conquered were shown to the people of Rome; thus, after the conquest of Britain essedarii exhibited in the arena the tactics of chariot fighting which Caesar had described several generations before in his Commentaries. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“It was natural enough, too, for the people to want to see different arms and different tactics tried against one another, and so the Samnite was matched against the Thracian, the heavy-armed against the light-armed. This became under the Empire the favorite style of combat. Finally, when people had tired of the regular shows, novelties were introduced that seem to us grotesque; men fought blindfold (andabatae), or armed with two swords (dimachaeri), or with the lasso (laqueatores), or with a heavy net (retiarii). There were also battles of dwarfs and of dwarfs with women. Of these the retiarius became immensely popular. He carried a huge net in which he tried to entangle his opponent, always a secutor, dispatching him with a dagger if the throw was successful. If unsuccessful he took to flight while preparing his net for another throw; or if he had lost his net, he tried to keep his opponent off with a heavy three-pronged spear (fuscina), his only weapon besides the dagger. |+|

Gladiator Armor and Weapons

Gladiator helmet Gladiators wore armor on their heads and other parts of the body, scholars believe, because battles in which gladiators were quickly put down with a blow to the head were not be very interesting for spectators to watch. The armor prolonged the battles and made the contest more challenging and sporting.

The armor, often weighing 13 kilogramns (30 pounds) or more, was specially designed for gladiator events. The helmets, with their fearsome-looking face guards, were extremely heavy but well balanced so they didn't put too much strain on the neck. Shields were made of wood because they were lighter than metal ones. They were often lined with felt to absorb the shock of the blows. The leg and arms guards were protected with linen or wool and felt linings were put under the helmets for the same reason. Peter Conolly, a historian and expert on gladiators, told Discover magazine: “The metal won't protect you from the blow, and this is particularly so with helmets. If someone belts you on the head, the helmet might stop the blow but it will knock you out." The main problem with the lining was it made the armor extremely hot.

About a dozen different weapons were used, some of which were based on weapons used on the battlefields against the Roman legions by their different enemies. Short swords were often preferred to long ones because they were more maneuverable and ideal for slashing. The fighting was less like a fencing match than a free for all with wild swings and wrestling. Swords were often kept behind shields until a move was ready to be made. Other weapons included pitch forks tied to the ankles, whips, clubs and the cestus, an iron-studded leather thong which could cause death if landed squarely on the temple. Sometimes combatants had one arm tied or were bound to metal plates. Sometimes one combatant was given the advantage of a shield, a piece of armor or a helmet that his opponent didn't have.

The armor and weapons used in these combats are known from pieces found in various places, and from paintings and sculpture, but we are not always able to assign them to definite classes of gladiators. The oldest class of gladiators were the Samnites. They had belts, thick sleeves on the right arm (manicae), helmets with visors, greaves on the left leg, short swords, and the long shield (scutum). Under the Empire the name Samnite was gradually, lost, and gladiators with equivalent equipment were called hoplomachi (heavy-armed), when they were matched against the lighter-armed Thracians, and secutores, when they fought with the retiarii. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The Thracians had much the same equipment as the Samnites; the marks of distinction were the small shield (parma) in place of the scutum and, to make up the difference, greaves on both legs. They carried a curved sword. The Gauls were heavy-armed, but we do not know how they were distinguished from the Samnites. In later times they were called murmillones, perhaps from an ornament on their helmets shaped like a fish (mormyr). The retiarii had no defensive armor except a leather protection for the shoulder. Of course, the same man might appear by turns as Samnite, Thracian, etc., if he was skilled in the use of the various weapons. |+|

On what it's like to wear gladiator armor, Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: The gladiator helmet I’ve just put on is stifling. A replica of the head protection worn by a Roman gladiator almost 2,000 years ago, the dented, scratched helmet weighs more than 13 pounds — three times as heavy as a football helmet, and far less comfortable. It has a tangy metallic smell, as though I’ve put my head inside a sweaty penny. Through the bronze grate covering my eyes, I can make out a pair of men in loincloths warming up for a fight. Metal armguards jingle as one bounces on the balls of his feet, his stubby, hooked sword clutched in a leather-gloved hand. As I shift uncomfortably, his partner lifts his sword and offers to hit me in the head, just to demonstrate how solid the helmet is.Loaded down with shields, metal leg guards and armguards, and hefty, full-coverage bronze helmets, many gladiators carried almost as much protective gear into the arena as Roman soldiers wore into battle. Yet their swords were typically about a foot long, barely bigger than a chef’s knife. “Why,” Brice Lopez, a former French police officer and gladiator afficionado, asks, “would you bring 20 kilos [45 pounds] of protective gear to a knife fight?” [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, July 20, 2021]

Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Gladiator Fighting Styles

Provocator versus Murmillio

Professor Kathleen Coleman of Harvard University wrote for the BBC: “The rules were probably specific to different styles of combat. Gladiators were individually armed in various combinations, each combination imposing its own fighting-style. Gladiators who were paired against an opponent in the same style were relatively uncommon. One such type was that of the equites, literally 'horsemen', so called because they entered the arena on horseback, although for the crucial stage of the combat they dismounted to fight on foot. [Source: Professor Kathleen Coleman, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Some of the most popular pairings pitted contrasting advantages and disadvantages against one another. Combat between the murmillo ('fish-fighter', so called from the logo on his helmet) and the thraex or hoplomachus was a standard favourite. The murmillo had a large, oblong shield that covered his body from shoulder to calf; it afforded stout protection, but was very unwieldy. The thraex, on the other hand, carried a small square shield that covered only his torso, and the hoplomachus carried an even smaller round one. |::|

“Instead of calf-length greaves, both these types wore leg-protectors that came well above the knee. So the murmillo and his opponent were comparably protected, but the size and weight of their shields would have called for different fighting techniques, contributing to the interest and suspense of the engagement. |::|

“The most vulnerable of all gladiators was the net-fighter (retiarius), who had only a shoulder-guard (galerus) on his left arm to protect him. Being relatively unencumbered, however, he could move nimbly to inflict a blow from his trident at relatively long range, cast his net over his opponent, and then close in with his short dagger for the face-off. He customarily fought the heavily-armed secutor who, although virtually impregnable, lumbered under the weight of his armour. As the retiarius advanced, leading with his left shoulder and wielding the trident in his right hand, his shoulder-guard prevented his opponent from striking the vulnerable area of his neck and face. |::|

“Not that all gladiators were right-handed. A disconcerting advantage accrued to the left-handed; they were trained to fight right-handers, but their opponents, unaccustomed to being approached from this angle, could be thrown off-balance by a left-handed attack. Left-handedness is hence a quality advertised in graffiti and epitaphs alike. |::|

“Originally the different fighting-styles must have evolved from types of combat that the Romans met among the peoples whom they fought and conquered - thraex literally means an inhabitant of Thrace, the inhospitable land bordered on the north by the Danube and on the east by the notorious Black Sea. Subsequently, as the fighting-styles became stereotyped and formalised, a gladiator might be trained in an 'ethnic' style quite different from his actual place of origin. It also became politically incorrect to persist in naming styles after peoples who had by now been comfortably assimilated into the empire, and granted privileged relationships with Rome. Hence by the Augustan period the term murmillo replaced the old term samnis, designating a people south of Rome who had long since been subjugated by the Romans and absorbed into their culture. |::|

Secutor

Secutor means pursuer. Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic History, "Wearing an armguard and carrying only a shield and sword resembling those used Roman legionnaires, he was mobile enough to chase his usual opponent, the net-wielding retiarius, around the ring. The secutor’s helmet was smooth and egg-shaped to prevent it from getting caught on a retiarius’s net. With just two eyeholes, the helmet must have been hard to see or breathe through, a handicap that balanced out bouts with this gladiator’s bareheaded foe. [Source Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

Susanna Shadrake wrote in “The World of the Gladiator”: “The first thing to note about the secutor is the name: meaning ‘chaser, pursuer’, it hints at the reason for this particular gladiator’s existence. Otherwise known as the contraretiarius, the secutor fought the retiarius; it is thought that the category was specially created for that purpose; if that origin is authentic, then there is some justification for thinking that the secutor was an offshoot of the murmillo. [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake \=/]

“In a nutshell, the arms and armour of the secutor were the same as those of the murmillo, and only the form of the helmet differed; it was brimless and had only a low, smooth, featureless crest following the curve of the bowl. The back of the helmet curled into a small neck-guard. Unlike other helmets with metal grilles forming the upper half of the visor, the secutor helmet enclosed the face completely; the visor had only two small eyeholes, each a scant inch (3 cm) in diameter, and although it was hinged to open from the side, it had a catch on the exterior to ‘lock’ the gladiator in it. \=/

Retiarius

Retiarius versus Secutor

The Retiarius, or “net man,” was a gladiator that used no shield and often had no helmet or footwear. He welded a three-pointed trident, dagger and weighted net in combat and had metal protectors on his left shoulder and arm. The retiarius’s equipment was styled on that of a fisherman: Typically, his clothing consisted only of a loincloth (subligaculum) held in place by a wide belt, or of a short tunic with light padding. He was an arena staple and typically paired with a secutor.

Susanna Shadrake wrote in “The World of the Gladiator”: Of all the gladiator categories, the most instantly recognisable is that of the retiarius, the net and trident fighter, named after the net he used, rete. Until halfway through the first century AD, there is no record, whether pictorial, literary, or archaeological, of this type of gladiator. After that point, the traditional pairing of retiarius and secutor starts to appear regularly, quickly becoming one of the most popular and enduring of the arena combats. From this, it is fair to assume that the secutor was invented at the same time as the retiarius, in order to create an exciting and novel combat; nothing like it can be detected at any earlier point in the historical record. The reason for the comparatively sudden appearance of this type of fighter cannot even be guessed at, and the usual sources are silent on the subject. All other categories of gladiator have an originating connection, however weak, with military or martial activities; the retiarius, with his obvious fishing and sea-related equipment, does not follow that pattern. The best we can do is to agree that the Roman appetite for watching new and inventive ways of killing was once again being gratified by this innovatory combat. \=/

“So many depictions of the retiarius show him holding the trident with both hands, with the left arm (as that is usually the leading arm for right-handers) forward and the right arm back at an angle, ready to thrust, that this is possibly the textbook stance for trident fighting. His body armour consisted solely of a high metal shoulder-guard, the galerus, on his left, or leading, shoulder, overlapping and affixed to the top edge of a manica protecting the left arm. Of course, this presupposes that the retiarius was right-handed, and that he would therefore cast his net with his right hand, while gripping his trident and dagger in the left hand. However, in a fragment of relief, one of the very few representations of this gladiator to actually show him with a net (from Chester, Cheshire, and now in Saffron Walden Museum), he is holding it in his left hand. He wore no helmet and is often depicted with a knife as a secondary weapon. “ \=/

In contests the retiarius was often pitted against the heavily armed secutor. Retiarius wore seven to eight kilograms (15-18 pounds) of armor while a Secutor wore 15 to 18 kilograms (35-40 pounds) or armor. Sometimes one retarius took on two secutores. A platform with stones to throw helped even the odds. The dagger was the retiarius's final backup should the trident be lost. It was reserved for when close combat or a straight wrestling match had to settle the bout.

The retiarius made up for his lack of protective gear by using his speed and agility to avoid his opponent's attacks and waiting for the opportunity to strike. He first tried to throw his net over his rival. If this succeeded, he attacked with his trident while his adversary was entangled. Another tactic was to ensnare his enemy's weapon in the net and pull it out of his grasp, leaving the opponent defenceless. Should the net miss or the secutor grab hold of it, the retiarius likely discarded the weapon, although he might try to collect it back for a second cast. Usually, the retiarius had to rely on his trident and dagger to finish the fight. The trident, as tall as a human being, permitted the gladiator to jab quickly, keep his distance, and easily cause bleeding. It was not a strong weapon, usually inflicting non-fatal wounds so that the fight could be prolonged for the sake of entertainment.

Provocator and Samnites

The Provocator was a gladiator who wore a significant amount of armor. In addition to his sword he was equipped with a breastplate and wore a helmet with visor and neck guard, along with a rectangular shield. He had a greave (shin guard) on his left knee.

Susanna Shadrake wrote in “The World of the Gladiator”: “The provocator in the imperial period remained very similar to his republican counterpart.The essential element of the provocator was his tradition of reflecting a military origin, but once this armatura was added to the gladiatorial categories, its distinct features ceased to move with the times; the connection with the military was forgotten, and the modifications to the equipment reflected the changing fashions in arena combat, and nothing more. [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake \=/]

“The provocator in the later imperial period sometimes wore a crescent shaped short breastplate, rather than a rectangular one, and the open helmet of legionary type became a visored one, as the cheek-pieces were expanded to meet in the middle, then hinged at the sides, and eye-grilles were added to enclose the face. All other items of equipment remained broadly the same. Depictions of Provocators usually show them fighting each other and no other variety of gladiator.”

A Samnite was a Roman gladiator who fought with equipment styled on that of Samnite warrior from Samnium (a region of Southern Italy): a short sword (gladius), a rectangular shield (scutum), a greave (ocrea), and a helmet. Warriors armed in such a way were the earliest gladiators in the Roman games. They appeared in Rome shortly after the defeat of Samnium in the 4th century BC, apparently adopted from the victory celebrations of Rome's allies in Campania. By arming low-status gladiators in the manner of a defeated foe, Romans mocked the Samnites and appropriated martial elements of their culture. Samnites were quite popular during the period of Roman Republic. Eventually, other gladiator types joined the roster, such as the murmillo and the Thraex. Under the reign of Emperor Augustus, Samnium became an ally and integral part of the Roman Empire (all Italians had by this point gained Roman citizenship). The Samnite was replaced by similarly armed gladiators, including the hoplomachus and the secutor. [Source: Wikipedia]

Thraex (Thracian)

The Thraex (Thracian) was easily recognized by his sica (short j-shaped sword), a small oblong shield and a helmet with an image of a griffin. He was lightly armored, with just leg and arm protectors, forcing him to rely on speed and agility to defeat his opponent. They often fought without a shirt. A pair of leg protectors, which covered the legs to the groin, worn by a thraex-style gladiator in Pompeii, were elaborately decorated with storks fighting snakes. One image of a female gladiator showed her dressed as a Thraex. [Source Owen Jarus. Live Science, August 17, 2022; Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

Susanna Shadrake wrote in “The World of the Gladiator”: This older category of gladiator was so popular, it did not disappear or mutate into another named type; however, the thraex did acquire new elements as time went on. Fashions changed in the arena, but it is possible to recognise the distinct armature of the thraex, whatever the date. [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake \=/]

The thraex carried a small square or rectangular shield, of wooden construction, planking or ply with a covering of leather, known as the parma or its diminutive, parmula; from examples depicted, it appears to have been emphatically convex rather than flat, and tended not to have a boss. From this shield, the thraeces got their popular nickname, parmularii, just as their opponents with the curved rectilinear shields were called scutarii.

Both the Murmillo and Thraex wore 15 to 18 kilograms (35-40 pounds) of heavy armor. Because the shield was small, about twenty four inches by twenty inches, and offered little protection below groin level, the thraex wore greaves, ocreae, on both legs, which reached up as far as mid-thigh, and is often depicted wearing a form of leg protectors above them, from at least knee to groin, which appear to be padded or quilted fabric wrappings around both legs. On the dominant arm a manica was worn. The primary weapon of this category was the curved bladed sica, depictions of this vary from dagger to sword length.

“The most instantly recognizable feature of the thraex was his brimmed, crested helmet with its distinctive griffin’s head. In all but a very few depictions of thraeces, the griffin is shown on the crest of the helmet, aiding identification. The significance of this particular mythological creature in a gladiatorial context may stem from its role as a guardian of the dead, or from a reputed association with Nemesis; four griffins were said to draw her chariot. As a symbol, the griffin frequently occurs in Greek and Roman art, and particularly at tombs, as a protector of souls. \=/

Murmillo

The tank of the arena, the Murmillo wore a full-coverage, visored helmet with a distinctive crest at the top. He was equipped with a large shin-to-shoulder shield that was oblong in shape and leg guards. His weapon was a short sword, called a gladius, based on the standard weapon of Roman legionaries. He was often matched up against the Thraex and, because of his larger shield, had the advantage when facing him. The metal face guard of Murmillo helmet could weigh two to four kilograms (4.5 to 9 pounds) and be one to two centimeters (.04 to .08 inches) thick. [Source Owen Jarus. Live Science, August 17, 2022]

Murmillo are perhaps named for a fish that decorated his helmet. The heavy armor of the Murmillo weighed 15 to 18 kilograms (35-40 pounds). They were also often against hoplomachus. Using weapons modeled on Thracian warriors they were known to be especially quick. Susanna Shadrake wrote in “The World of the Gladiator”: “The Murmillo gets his name from the Greek word for a type of fish, as many contemporary sources indicated, it was derived from the image of a fish on their helmets, although the archaeological record has no firm evidence to support that assertion. The fish in question was the mormyros, or in Latin, murmo or murmuros, the striped bream, which was very common in the Mediterranean then as now, and best caught by the age-old method of surf-casting, a fishing technique involving casting the net into the surf to trap the fish coming in from the sandy bottoms where they feed. It is in this technique that perhaps a clue to the origin of the murmillo may be found. [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake \=/]

The emperor Vespasian’s rhetorician, Quintilian, records a sing-song chant supposedly addressed to a murmillo by a pursuing retiarius: ‘Non te peto, piscem peto; cur me fugis, Galle?’ (‘It’s not you I’m after, it’s your fish; why are you running away from me, Gaul?’.) If there is any historical authenticity at all in this jeering provocation of the heavy-armoured murmillo, it reveals two things; firstly, a clever and realistic tactic by the retiarius — to exhaust his opponent by baiting him into excessive movement, and secondly, the net-man’s reference to the fish emblem on the helmet, identifying the other gladiator as murmillo, but calling him ‘Gaul’. Whatever the origin of the term murmillo, it is generally believed that they evolved from the earlier category known as the Gaul, or gallus, about which little is known. \=/

“We do know however that the murmillo wore a manica, an arm guard, on his sword arm. He carried the large rectangular semi-cylindrical wooden shield very similar in appearance and construction to the legionary scutum. On his left leg was a short greave worn over padding. Unlike the thraex or hoplomachus, the murmillo, having the almost complete cover of the very large shield, the scutum, did not need the high, thigh length greaves that they wore—so long as there was sufficient overlap between the bottom of the shield and the top of the greave, his defence was maintained. \=/

“The murmillo was armed with the gladius. The helmet of the murmillo had a broad brim, with a bulging face-plate that included grillwork eye-pieces; its distinctive appearance was partly due to the prominent visor, but also to the angular, sometimes hollow, box crest which was then able to take the insertion of a wooden plume-holder into which a further horsehair (or feathered) crest could be fixed. Single plume-holders for feathers were fixed on either side of the bowl. “In common with most of the categories of gladiator, the torso of the murmillo was, as we have seen, exposed, and he wore the subligaria, the elaborate folded loincloth together with the balteus, the ostentatiously wide belt, often highly decorated. A good example of the lavishness of the ornamentation of belts is shown in the bone figure of a murmillo gladiator from Lexden, Colchester. \=/

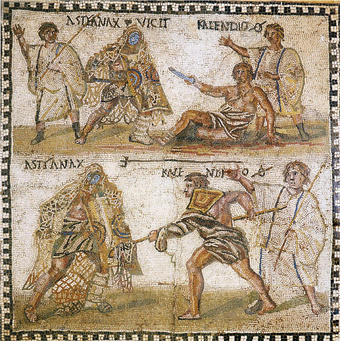

Murillo Verus Retiarius Fight

Tolga İldun wrote in Archaeology magazine: The sun illuminated the stadium in Ephesus, a wealthy harbor city in western Anatolia, on a day of eagerly anticipated gladiatorial combat. Festive decorations adorned the arena, and the air was filled with the scent of refreshing perfumed water sprayed over the crowd. As the gladiators were announced, they paraded before the spectators to the strains of music, displaying their powerful physiques and their readiness to fight. All eyes were drawn to two combatants in particular: Margarites, known as the “Pearl of the Arena,” and Palumbos, whose stage name was the “Male Dove.” By the time the sun was high overhead, the arena was packed to capacity. A horn signaled the start of the afternoon’s games. [Source Tolga İldun, Archaeology magazine, November-December, 2024 archaeology.org]

A pair of mounted gladiators featured in the initial spectacle, but the highlight was the duel between Margarites and Palumbos. Margarites, clad only in a small loincloth secured by a wide belt, wielded a net and trident—classic armaments of his type of gladiator, the retiarius, whose light weapons facilitated speed and agility. Palumbos was a formidable murmillo, whose large helmet, wooden shield, and gladius—the style of short sword that lent the profession its name—augmented his imposing stance. As the combat began, Margarites deftly cast his net toward Palumbos, attempting to ensnare him. Palumbos, despite the weight of his armor and shield, skillfully eluded the gambit. Margarites circled the arena searching for an opening, while Palumbos remained patient. The contrast between the retiarius’ speed and the murmillo’s endurance became evident. As time passed, fatigue began to weigh on Margarites. In a final effort, he launched his net once more, but Palumbos evaded him again and countered with a swift sword strike. Recognizing impending defeat, Margarites dropped his weapons, signaling surrender.

The expectant crowd awaited a verdict. Some cried “Iugula!” (Cut his throat!), while others yelled “Missus!” (Reprieved!). Margarites’ dignified composure swayed the games’ patron, who indicated the gladiator’s life should be spared. As the victorious Palumbos departed, Margarites, too, left the arena with the spectators’ respect. Both men would live to fight another day, and this battle would be remembered for years to come.

Exotic Gladiators

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic History: Despite these fan favorites that appeared at every match, crowds always loved a surprise. Literary sources and tombstones include references to a variety of more exotic gladiator types deployed to add a splash of excitement to the familiar lineup. Some included the essedarius, who thundered into the ring in a horse-drawn chariot; the scissor, who wielded a curved, half-moon-shaped knife perfect for cutting the retiarius’s net; and the laquearius, equipped with a long lasso to snare his foe. Fighters who could switch back and forth between two fighting styles were remarkable enough that this skill was sometimes mentioned on their tombstones.[Source Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In 2014, a traditional dig in Carnuntum’s ludus turned up a metal plate that probably came from the scale armor of a scissor, a type of gladiator sometimes paired with a retiarius. What distinguished the scissor was the hollow steel tube into which his forearm and fist fitted. The tube was capped: At the business end was a crescent-shaped blade meant to cut through the retiarius’ net in the event of entanglement. [Source:Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2016]

Eques and Essedarius

Eques were gladiators who fought on horseback armed with a bronze shield and spear. Eques is derived from the same word that gives us equestrian (horse-related). The equites were a social class in ancient Rome that were defined by their wealth and were often called knights. The equites were the second highest class in Roman society, below the senatorial order

According to Live Science: One early medieval source suggests that the Eques, when they fought, were the opening act in gladiator games. "Two equites, preceded by military standards, entered the arena, one from the west, the other from the east, riding on white horses, wearing smallish golden helmets and carrying light weapons," writes Isidore of Seville in the seventh century. Presumably they started fighting with lances and switched to swords if dismounted. [Source Owen Jarus. Live Science, August 17, 2022^^]

Evidence suggests that eques only fought other eques. They were equipped with lance, sword and the traditional small round shield of the republican cavalry, the parma equestris, and wore distinctive uncrested, round-brimmed helmets with feathers at either side. They did not wear a loincloth unlike the other categories of gladiator. In earlier images of they wore scale-armour. Later images show them in knee-length tunica. Depictions of imperial equites usually have them wearing capacious tunics, sometimes brightly coloured and decorated.” [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake]

Essedarius means "one who fought from a chariot". These gladiators typically started the contest in a chariot but finished it on foot. It is thought they fought each other. The lack of surviving images of them means that scholars know little about their tactics or their equipment. ^^

Hoplomachus and Crupellarius

The Hoplomachus was similar to an ancient Greek hoplite, the kind of soldier that fought under Alexander the Great. Armed primarily with a thrusting spear, he carried a small circular shield and wore an armguard on his right arm. Susanna Shadrake wrote in “The World of the Gladiator”: “The Hoplomachus is often confused with the thraex, and indeed they have many pieces of equipment in common. The word is from the Greek, meaning simply ‘armed fighter’. They both had the distinctive forward-curving crested visored helmet, though that of the hoplomachus did not appear to have the griffin’s head on its crest. Both had the same high greaves, and padded leg wrappings, fasciae. They even shared the same opponent, the murmillo. But whereas the shield, parmula, of the thraex was small and square or rectangular, that of the hoplomachus was round, though still small in size. [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake \=/

The shield was always round, convex, and made of a single sheet of metal, usually copper-alloy (bronze). The thickness of the sheet bronze was an important factor in determining the weight of the shield—too thick, and its defensive qualities would be negated by its unwieldiness. The primary weapon of this category seems to have been the spear, that the other weapon of the hoplomachus, the sword, or perhaps a longer dagger, like the pugio, could be held in the left hand at the same time as the shield, ready for use once the spear was cast or lost. \=/

The crupellarius was an extremely heavily armed gladiator whose origin was Gaul. They are first mentioned by the first century A.D. historian, Tacitus. In an account of the revolt of Julius Florus and Julius Sacrovir in AD21, the crupellarii, heavily armoured Gallic gladiators fought against the Roman legionaries. Tacitus gives a colourful account of the outcome: “Completely encased in iron in the national fashion, these crupellarii, as they were called, were too clumsy for offensive purposes but impregnable in defence……the infantry made a frontal attack. The Gallic flanks were driven in. The iron-clad contingent caused some delay as their casing resisted javelins and swords. However the Romans used axes and mattocks and struck at their plating and its wearers like men demolishing a wall. Others knocked down the immobile gladiators with poles or pitchforks, and, lacking the power to rise, they were left for dead.” [Tacitus Annales III. 43] Gladiators with that amount of heavy armour were unknown elsewhere in the Roman empire, but a small figurine found at Versigny, France, fitting the description of a crupellarius, shows a ‘robotic’ looking gladiator clad almost entirely in plate armour from head to foot. The helmet has a perforated bucket appearance.” \=/

Comedic Gladiators

Susanna Shadrake wrote in “The World of the Gladiator”: The paegniarii seem to have been comedy fighters, whose combats did not involve sharp weapons and were played strictly for laughs. They have an ancient pedigree, more related to the Atellian farces from which they seem to have strayed. They would presumably have been deployed in the intervals between more bloodthirsty parts of the programme, at lunchtime perhaps, to hold the crowd’s interest and to provide light relief. [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake \=/]

A variant on the usual paegniarius was offered by Caligula, who, as Suetonius relates, ‘would stage comic duels between respectable householders who happened to be physically disabled in some way or other’. In depictions of paegniarii, they do not wear armour, and carry non-lethal weapons, like whips and sticks. So the knockabout contests they performed would not have presented much danger to life and limb”. One famous paegniarii lived to the age of 97. \=/

Women Gladiators

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Researcher Alfonso Manas has identified a small bronze statue, now in a museum in Germany, as being a depiction of a female gladiator. If this is correct it will be only the second image of a female gladiator known to exist. She is shown raising a small curved sword, known as a sica, in victory, and looking down at the ground, presumably at her fallen opponent, Manas reports in the International Journal of the History of Sport. The female gladiator appears to have fought as a Thraex, Notably the female gladiator is depicted without the helmet, possibly because she took it off for the victory gesture. This picture shows a modern-day re-creation of a Thraex gladiator about to compete in a mock fight; notice that men, when they competed as a Thraex, fought topless as well. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, August 17, 2022]

Female gladiators were called gladiatrices, with gladiatrix being the singular form. While the first documented appearance of gladiatrices appears under the reign of Nero (37 – 68 AD), there is evidence in earlier documents that strongly suggest they existed before. Emperor Severus banned female gladiators around AD 200 but records show that this ban was largely ignored.” [Source: Jamie Frater, Listverse, May 5, 2008]

Shandrake wrote: “The subject of female gladiators has always aroused strong emotions; then as now, they have been seen as aberrations or novelties. There are a few references to women fighters in the literary sources, and some evidence from inscriptions on monuments. From these pieces of evidence, the existence of the gladiatrix as an authentic gladiatorial category rather than a fevered fantasy can be established; however, proof of existence is not the same as a guarantee of frequency of occurrence. [Source: “The World of the Gladiator” by Susanna Shadrake \=/]

In Satire VI, Juvenal dismissed female gladiators in the A.D. late 1st century and early 2nd century as upper-class snots seeking excitement and fame. Juvenal wrote: “Everyone knows about the purple wraps and the women’s wrestling floors. And everyone’s seen the battered training post, hacked away by her repeated sword thrusts and bashed by her shield. The lady goes through all the drill, absolutely qualified for the trumpet at the festival of Flora. Unless, of course, in her heart she’s planning something more and is practising for the real arena. What sense of modesty can you find in a woman wearing a helmet, who runs away from her own gender?

"It’s violence she likes. All the same, she wouldn’t want to be a man—after all, the pleasure we experience is so little in comparison! What a fine sight it would be if there were an auction of your wife’s things—her sword belt and her arm protectors and her crests and the half-size shin guard for her left leg! Or, if it’s a different kind of battle that she fights, you’ll be in bliss as your girl sells off her greaves! Yet these are women who break out into a sweat in the thinnest wrap and whose delicate skin is chafed by the finest wisp of silk. Hark at her roaring while she drives home the thrusts she’s been taught. Hark at the weight of the helmet that has her wilting, at the size and the thickness of the bandages that surround her knees—and then have a laugh when she takes off her armour to pick up the chamber pot.” [Juvenal, Satirae VI 246-264]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024