Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

COLOSSEUM

The Colosseum — known in Roman times as the Flavian Amphitheater — has been called "a perfect expression of the brilliance and brutality that were Rome." Begun by Vespasian, the commander who had "subdued" the Jews, and completed a decade later by his son Titus, it was erected on land once taken for private parkland by the odious and was said to have been built by thousands of Jewish slaves brought from Palestine after the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70, and completed in A.D. 80 , it had a capacity of 50,000 to 75,000 people (depending on who's doing the counting) and was in use for almost 500 years.

The Colosseum is an egg-shaped amphitheater. When full, Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “a crowd of 50,000 Roman citizens sat according to their place in the social hierarchy, ranging from slaves and women in the upper bleachers to senators and vestal virgins — priestesses of Vesta, goddess of the hearth — around the arena floor. A place of honor was reserved for the editor, the person who organized and paid for the games. Often the editor was the emperor himself, who sat in the imperial box at the center of the long northern curve of the stadium, where his every reaction was scrutinized by the audience."

The Colosseum attracts close to eight million tourists a year, making it one of the world’s most-visited archaeological attractions. When it opened it must have been an even more impressive sight than it is today. It was originally covered in blocks of hard travertine stone and white marble, which have been scavenged piece by piece over the centuries for the construction of other buildings, often under the auspices of the Popes, who insisted the Colosseum be preserved as symbol of Christian martyrdom. The only original marble pieces that remain are a few scattered pedestals and pillars. What viewers see today are remains of the concrete core, the brick superstructure and with miles of vaulted corridors. After a $1.4 million renovation the hypogeum was opened to the public in October, 2010. A section of the arena floor has been reconstructed to give some sense of how the stadium looked in its day.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: LAYOUT, ARCHITECTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

PUBLIC GAMES AND SHOWS OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS europe.factsanddetails.com

NAUMACHIAE — GIANT ROMAN STAGED SEA BATTLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN SPORT: BALL GAMES AND FIXED WRESTLING MATCHES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECREATION IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Colosseum: Design - Construction - Events” by Nigel Rodgers (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Colosseum (Wonders of the World)” by Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard (Harvard University Press, 2005); Amazon.com;

“The Colosseum” edited by Ada Gabucci (Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 2001)

Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Architecture” Gene Waddell (2017) Amazon.com;

“Roman Architecture” by Frank Sear (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Amphitheatre: From its Origins to the Colosseum” by Katherine E. Welch (2007) Amazon.com

“The Roman Games: A Sourcebook (Blackwell) by Alison Futrell Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Spectacle in the Roman World” by Hazel Dodge (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Day Commodus Killed a Rhino: Understanding the Roman Games” (Witness to Ancient History) by Jerry Toner (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Sourcebook” by Anne Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide” by Paul Plass (1995) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

Colosseum — Symbol of Rome and Source of Its Name

Wenceslas_Hollar.jpg)

Colosseum (State_1) by Wenceslas Hollar The Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater) is the best known of all the buildings of ancient Rome, because to so large an extent it has survived to the present day.” To truly appreciate it is worth comparing it to “its modest prototype in Pompeii. The latter was built in the outskirts of the city, in a corner, in fact, of the city walls; the Colosseum lay near the center of Rome, and was easily accessible from all directions. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

Keith Hopkins of the University of Cambridge wrote for the BBC: “The ordered beauty of the Colosseum is in stark contrast to the murderous encounters that took place within it. Find a seat not too close to the action, for an inkling of what Romans got up to, in ancient times. Even today, in a world of skyscrapers, the Colosseum is hugely impressive. It stands as a glorious but troubling monument to Roman imperial power and cruelty. Inside it, behind those serried ranks of arches and columns, Romans for centuries cold-bloodedly killed literally thousands of people whom they saw as criminals, as well as professional fighters and animals. [Source: Keith Hopkins, BBC, March 22, 2011 |::|]

“Indeed, it was the amphitheater's reputation as a sacred spot where Christian martyrs had met their fate that saved the Colosseum from further depredations by Roman popes and aristocrats - anxious to use its once glistening stone for their palaces and churches. The cathedrals of St Peter and St John Lateran, the Palazzo Venezia and the Tiber's river defences, for example, all exploited the Colosseum as a convenient quarry. As a result of this plunder, and also because of fires and earthquakes, two thirds of the original have been destroyed, so that the present Colosseum is only a shadow of its former self, a noble ruin.” |::|

Federico Gurgone wrote in Archaeology magazine: The Colosseum actually acquired its name from the giant bronze statue that Nero had commissioned of himself to resemble the Colossus at Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. In his continuing effort to banish all memory of the disgraced emperor, Vespasian added a crown to the statue and rededicated it to the Roman sun god, Sol. Around A.D. 128, the emperor Hadrian had the statue moved to the northwest side of what was then known as the Flavian Amphitheater — after the new imperial dynasty founded by Vespasian — thus permanently associating the building with the statue, even after the statue itself was gone. The Domus Aurea was the site of Nero’s Golden Palace, which was stripped of many of its fine decorations, and its vaulted spaces were filled with earth, providing a level surface upon which the massive public baths of the emperors Titus and Trajan were constructed. [Source: Federico Gurgone, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2015]

History of the Colosseum

The first permanent amphitheater was that built in 29 B.C. at Rome by a friend of the princeps around Statilius Taurus. It was situated to the south of the Campus Martius and was destroyed in the great fire of A.D. 64 during the reign of Nero A.D. 54-68). The Flavians decided almost at once to replace it by a larger one of the same design. It was started by Vespasian, completed by Titus, and decorated by Diocletian. This amphitheater is now called the Colosseum. The Colosseum stands between the Velia, the Caelius, and the Esquiline, near the colossus of the sun within the domain of Nero's Golden House, (Domus Aurea), where one of the costly fish-ponds of Nero (stagnum Neronis) was expressly filled in for the purpose. Some say the Colosseum was originally conceived by Emperor Vespasian as an apology gift to the people of Rome for all they endured under the previous Emperor, Nero.

Keith Hopkins of the University of Cambridge wrote for the BBC: “The Colosseum was started in the aftermath of Nero's extravagance and the rebellion by the Jews in Palestine against Roman rule. Nero, after the great fire at Rome in A.D. 64, had built a huge pleasure palace for himself (the Golden House) right in the centre of the city. In 68, faced with military uprisings, he committed suicide, and the empire was engulfed in civil wars. [Source: Keith Hopkins, BBC, March 22, 2011 |::|]

“The eventual winner Vespasian (emperor 69-79) decided to shore up his shaky regime by building an amphitheater, or pleasure palace for the people, out of the booty from the Jewish War - on the site of the lake in the gardens of Nero's palace. The Colosseum was a grand political gesture. Suitably for that great city, it was the largest amphitheater in the Roman world, capable of holding some 50,000 spectators. Eventually there were well over 250 amphitheaters in the Roman empire - so it is no surprise that the amphitheater and its associated shows are the quintessential symbols of Roman culture. |::|

.jpg)

Colosseum (State 2) “When the Colosseum opened in A.D. 80, Titus staged a sea-fight there (in about one metre of water), and recent research has shown convincingly that the amphitheater had no basement at this time. But the rivalrous brother of Titus, Domitian (emperor 81-96), was quick to have a basement built - with ring-formed walls and narrow passages. In this confined space, animals and their keepers, fighters, slaves and stage-hands toiled in the almost total darkness to bring pleasure to Romans.” |[Source: Keith Hopkins, BBC, March 22, 2011 |::|]

A fire sparked by lightning in A.D. 217 gutted the stadium and sent huge blocks of travertine plunging into the basement. In the A.D. 6th century, after about 500 years of blood and circuses, the Colosseum fell into disrepair. Later, it was used for living quarters and even as a cemetery. According to Archaeology magazine: Excavationa conducted by Roma Tre University and the American University of Rome beneath those entryways has revealed new evidence about the time, between the ninth and fourteenth centuries, when the Colosseum was home to more ordinary Roman citizens. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, local friars who controlled the property rented out the space and transformed the Colosseum into a makeshift condominium complex. Stables, workshops, and private residences lined the communal courtyard, creating a kind of medieval bazaar where bloody contests once took place. Archaeologists have uncovered terracotta sewage pipes, cookware, and a carved ivory monkey figurine, likely used as a gaming piece. The Colosseum functioned in this capacity until 1349, when an earthquake struck Rome and rendered the building architecturally unsound. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2014]

Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “In the late 16th century, Pope Sixtus V, the builder of Renaissance Rome, tried to transform the Colosseum into a wool factory, with workshops on the arena floor and living quarters in the upper stories. But owing to the tremendous cost, the project was abandoned after he died in 1590. In the years that followed, the Colosseum became a popular destination for botanists due to the variety of plant life that had taken root among the ruins. As early as 1643, naturalists began compiling detailed catalogs of the flora, listing 337 different species. [Source: Tom Mueller, Smithsonian magazine, January 2011]

Colosseum Painted with Bright Colors And Covered by Graffiti Phalluses

Tom Kington wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Archaeologists scraping away centuries of grime covering the walls of the Colosseum in Rome have discovered that the massive amphitheater was once painted with riotous colors. Experts working on the walls of one of the corridors that once led Romans to their seats to watch bloody gladiatorial shows have discovered traces of brilliant reds, light blue, green and black, proving the drab gray stonework of the Colosseum was once a Technicolor feast. [Source: Tom Kington, Los Angeles Times, January 18, 2013]

“Graffiti celebrating gladiatorial triumphs and scrawled phalluses also can be found on the plasterwork, which has been painstakingly revealed by scraping off dirt and dust. “We have long suspected this range of colors was used. I have wanted to do this for 20 years,” said Rossella Rea, director of the Colosseum. The discoveries were made in a corridor closed to the public, 60 feet above the level of the arena. Rea said that the newly revealed colors were painted in the corridors that circled the arena, while the seating area was bright white, apart from the emperor’s luxury box, which was decked out in richly colored marble.

“Rea’s team also found symbols representing palm fronds and crowns painted on walls in the corridor, daubed by spectators to mark the victory in battle of a favorite gladiator. Experts have previously found images of gladiators scratched into the stone seating by spectators. Graffiti now exposed from that period include scribbled names and phalluses — “lots of phalluses,” said Rea. More recent signatures are dated 1826 and 1892, as curious visitors returned to the Colosseum.

Frescoes Discovered in the Colosseum

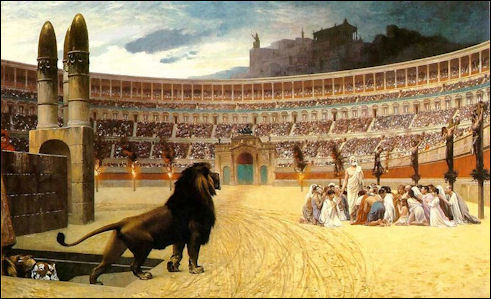

Christian Martyrs in the Colosseum In 2013, Italian restorers cleaning the Colosseum discovered the remains of frescoes indicating the interior of the Colosseum may have been decorated with murals as being colorfully painted .Naomi O'Leary of Reuters wrote: “Working in a passage closed to the public for decades, restorers scraped off years of limescale and black pollution from car exhaust to discover remains of the frescoes, their vivid red, blue, green and white colors still visible. “This is a beautiful archaeological surprise,” Mariarosaria Barbera, Rome’s archaeological superintendent told Reuters. “Even in a monument as well known as this one, studied all over the world, there are still new things to discover.” The team also discovered ancient sketches by spectators who painted crowns and palm trees, symbols of victory celebrating the success of gladiators they supported. The Latin word “VIND”, referring to victory or revenge, was also found. [Source: Naomi O'Leary, Reuters, January 19, 2013 ***]

“Restorers discovered the frescoes in a passage leading to the highest level of seating, a wooden gallery reserved for the lowest classes and furthest from the action in the arena. Senators had seats on the first floor, while the emperor and Vestal Virgin priestesses had special boxes with the best views. Blue pigment was a costly luxury at the time, so its use in a corridor leading to the cheap seats indicated the rest of the stadium’s interior may have been intricately decorated too, Barbera said. ***

“The frescoes likely date from after 217 AD, when a fire destroyed the wooden gallery that topped the Colosseum. The frescoes were discovered during the monument’s first comprehensive restoration in 73 years, a 25 million euro ($33.39 million) project to clean the entire building by 2015. Restorers have cleaned only a small part of the monument so far, and hope to reveal the detail of what the frescoes depict underneath marks left by centuries of visitors. Written in a modern script, the name “Luigi” was scratched into a well-preserved red section of fresco. Nearby was scrawled the date “1620”, and “J. Milber from Strasbourg, 1902”. ***

Archaeological Work at the Colosseum

Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “By the early 19th century, the hypogeum's floor lay buried under some 40 feet of earth, and all memory of its function — or even its existence — had been obliterated. In 1813 and 1874, archaeological excavations attempting to reach it were stymied by flooding groundwater. Finally, under Benito Mussolini's glorification of Classical Rome in the 1930s, workers cleared the hypogeum of earth for good. [Source: Tom Mueller, Smithsonian magazine, January 2011]

Heinz-Jürgen Beste of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome "and his colleagues spent four years using measuring tapes, plumb lines, spirit levels and generous quantities of paper and pencils to produce technical drawings of the entire hypogeum. “Today we'd probably use a laser scanner for this work, but if we did, we'd miss the fuller understanding that old-fashioned draftsmanship with pencil and paper gives you," Beste says. “When you do this slow, stubborn drawing, you're so focused that what you see goes deep into the brain. Gradually, as you work, the image of how things were takes shape in your subconscious."

Unraveling the site's tangled history, Beste identified four major building phases and numerous modifications over nearly 400 years of continuous use. Colosseum architects made some changes to allow new methods of stagecraft. Other changes were accidental;a fire sparked by lightning in A.D. 217 gutted the stadium and sent huge blocks of travertine plunging into the hypogeum. Beste also began to decipher the odd marks and incisions in the masonry, having had a solid grounding in Roman mechanical engineering from excavations in southern Italy, where he learned about catapults and other Roman war machines. He also studied the cranes that the Romans used to move large objects, such as 18-foot-tall marble blocks.

Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, When Beste and a team of German and Italian archaeolgists first began exploring the hypogeum, in 1996, he was baffled by the intricacy and sheer size of its structures: “I understood why this site had never been properly analyzed before then. Its complexity was downright horrifying." [Source: Tom Mueller, Smithsonian magazine, January 2011]

Christian Martyr's Last Prayer The disarray reflected some 1,500 years of neglect and haphazard construction projects, layered one upon another. After the last gladiatorial spectacles were held in the sixth century, Romans quarried stones from the Colosseum, which slowly succumbed to earthquakes and gravity. Down through the centuries, people filled the hypogeum with dirt and rubble, planted vegetable gardens, stored hay and dumped animal dung. In the amphitheater above, the enormous vaulted passages sheltered cobblers, blacksmiths, priests, glue-makers and money-changers, not to mention a fortress of the Frangipane, 12th-century warlords. By then, local legends and pilgrim guidebooks described the crumbling ring of the amphitheater's walls as a former temple to the sun. Necromancers went there at night to summon demons.

By applying his knowledge to eyewitness accounts of the Colosseum's games, Beste was able to engage in some deductive reverse engineering. Paired vertical channels that he found in certain walls, for example, seemed likely to be tracks for guiding cages or other compartments between the hypogeum and the arena. He'd been working at the site for about a year before he realized that the distinctive semicircular slices in the walls near the vertical channels were likely made to leave space for the revolving bars of large capstans that powered the lifting and lowering of cages and platforms. Then other archaeological elements fell into place, such as the holes in the floor, some with smooth bronze collars, for the capstan shafts, and the diagonal indentations for ramps. There were also square mortises that had held horizontal beams, which supported both the capstans and the flooring between the upper and lower stories of the hypogeum.

To test his ideas, Beste built three scale models. “We made them with the same materials that children use in kindergarten — toothpicks, cardboard, paste, tracing paper," he says. “But our measurements were precise, and the models helped us to understand how these lifts actually worked." Sure enough, all the pieces meshed into a compact, powerful elevator system, capable of quickly delivering wild beasts, scenery and equipment into the arena.

Renovations of the Colosseum

The Colosseum underwent an $40 million, three-phase restoration in the later 2010s and early 2020s funded by Tod’s, the Italian shoe and accessory company. The first phase was an extensive cleaning of the Colosseum’s façade. The opening up of tunnels in June 2021 heralded the finish of the the second stage. The third phase has concentrated the second level of seating. Plans call for a wooden stage to be built across the entire arena area. That $27 million project was announced in 2021. [Source: Nick Squires, The Telegraph, June 25, 2021]

After the tunnels were opened in 2021, Nick Squires wrote in The Telegraph: Visitors can descend a metal stairway and wander between the brick and travertine walls where armour-clad gladiators and wild animals such as leopards, lions and bears were corralled. Gathered in the subterranean gloom, they were hoisted into the arena in a series of wooden cage lifts that were operated with the muscle power of a legion of slaves, emerging via trap doors into the huge amphitheater, the biggest in the Roman world.

Visitors can see the original bronze fittings, sunk into travertine stone, that housed the capstans which enabled the cages to be raised and lowered. A small section of the hypogeum was opened about a decade ago, but now visitors can access the entire area. They can also see a fully-functioning wooden lift, complete with cage and capstans, which was reconstructed in 2015 for a television documentary about ancient Rome. There were originally 28 such wooden lifts, but after the Colosseum was remodeled following a fire in A.D. 217, that number increased to 60. “This is the very heart of the Colosseum. You can imagine how dark it would have been down here, full of men and animals and the people who organised the spectacles in the arena. In many ways, this is the most interesting part of the Colosseum. It’s a monument within the monument,” said Alfonsina Russo, the director of the Colosseum.

The lifts were used to hoist medium-sized animals such as leopards and wolves, while large animals such as elephants and rhinos entered through ground-level arches. “Lions, leopards, tigers and bears were among the animals that took part in the spectacles,” said Ms Russo. “They were managed by specially-trained trainers, a bit like a modern day circus.”

“Darius Arya, an archeologist, said the tunnels would have been hot, dark and claustrophobic. “You can imagine the sounds that would have permeated down from the arena above — animals crashing around, the screams of gladiators, the blood and guts. The gladiators were highly trained so they were not meant to be whimpering, but the animals would have been terrified. This would have been an extremely unpleasant place to be,” said Mr Arya, the director of the American Institute of Roman Culture. “They’ve done a great job with the walkway. It provides an amazing level of access.”

The brickwork has been painstakingly grouted to plug cracks and holes while the travertine marble blocks have been cleaned. Most of the work was done by hand, with experts using sponges, spatulas and manual drills. It involved a team of more than 80 technicians, engineers, architects and archeologists. “We hope this will be seen as a symbol of hope and recovery as Italy emerges from the pandemic,” said Dario Franceschini, the culture minister.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024