Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory / Life, Homes and Clothes

POMPEII

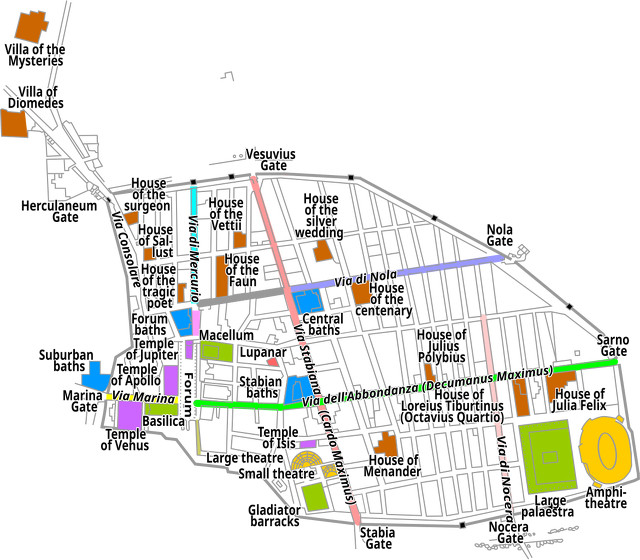

Pompeii (23 kilometers 14 miles) southeast of Naples) is the famous Roman town destroyed and entombed in ash by the huge A.D. 79 eruption of Vesuvius. Pompeii was a market town, port and resort for the wealthy with 10,000 to 20,000 inhabitants. The densely-built up streets and alleys were paved with stone and bordered by raised footsteps, shops, cafes and taverns. There were three public baths, two theaters, a 20,000-seat amphitheater, 4,000 residences and 30 bakeries. Water was supplied by an aqueduct that originated in the Lower Apennines mountains that had been completed shortly before Pompeii’s demise. Around the town was rich volcanic soil that yielded grapes for popular wines and other crops.

Pompeii (30 minutes by train from Naples and Sorrento) was first occupied by in the 4th century B.C. In the 2nd century B.C. most structures were modest houses and workshops. In the 1st century B.C. the town was bombarded by stone artillery shells by Roman troops. Later it became dominated by larger luxurious residences surrounded by bars and shops. The first masonry residences appeared in the 3rd century B.C. A typical large villa began as a modest house and expanded as property around it was bought up and new wings were added around a courtyard,

At the time of the eruption in A.D. 79 Titus was the Emperor of Rome (Vespasian had just passed away) and Pompeii had 13,000 year-round inhabitants and thousands more who came from Rome during the summer and lived in luxurious seaside villas. Pompeii’s patron deity was Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty, which might perhaps explain why the city was filled with so much erotic art. The catastrophic eruption of Vesuvius was not the only hardship the city endured. In 96 B.C. Pompeii was struck by a devastating earthquake. There was another in A.D. 62. Pompeii was still being rebuilt when the A.D. 79 eruption occurred. The hardened, fine-grained ash and rock from that eruption proved to be an excellent preservative, encasing objects like insects in amber.

Pompeii is the second most visited tourist site in Italy after the Colosseum in Rome, with just under four million visitors in 2019. Digs at Pompeii at that time revealed an inscription that proves that Pompeii was destroyed after October 17, 79 AD, and not on August 24 as thought. Archeologists in October 2019 discovered a vivid fresco depicting an armour-clad gladiator standing victorious over a wounded opponent gushing blood, painted in a tavern believed to have housed the fighters as well as prostitutes. [Source: Ella Ide, AFP, November 25, 2019]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ERUPTION OF VESUVIUS IN A.D. 79: EFFECTS, EARTHQUAKES AND PLINY THE ELDER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HOUSES AND VILLAS AT POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com

POMPEII ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POMPEII VICTIMS: THEIR LIVES, CASTS, DEATHS AND DNA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM VICTIMS: THEIR LIVES, DEATHS AND VAPORIZATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, BUILDINGS europe.factsanddetails.com

CITIES, TOWNS AND URBAN LIFE IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT ROME AS A CITY: LAYOUT, INFRASTRUCTURE, BUILDINGS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pompeii”, Illustrated, by Joanne Berry (2007) Amazon.com;

“Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Paul Roberts Amazon.com;

"Pompeii's Living Statues: Ancient Roman Lives Stolen from Death” by Eugene Dwyer | (2010) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (1996) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: An Archaeological Guide by Paul Wilkinson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii” by Robert Harris (2003), Novel Amazon.com

“Inside Pompeii”, a photographic tour, by Luigi Spina (2023) Amazon.com;

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Alison E. Cooley (2013) Amazon.com;

“Herculaneum: Italy's Buried Treasure” by Joseph Deiss (1989) Amazon.com;

“The Library of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by David Sider (2005) Amazon.com;

“Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by Kenneth Lapatin (2019) Amazon.com;

“Vesuvius: A Biography” by Alwyn Scarth (2009) Amazon.com;

“Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei, and Campanian Volcanism” by Benedetto De Vivo, Harvey E. Belkin, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Neapolitan Volcanoes: A Trip Around Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei and Ischia” (GeoGuide)

by Stefano Carlino (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Eruption of Vesuvius in 1872: Unveiling the Catastrophic Fury of Mount Vesuvius”

by Luigi Palmieri and Robert Mallet (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius” by Pedar W. Foss Amazon.com;

“The Letters of the Younger Pliny (Penguin Classics) by Pliny the Younger and Betty Radice (1963) Amazon.com;

“Ghosts of Vesuvius: A New Look at the Last Days of Pompeii, How Towers Fall, and Other Strange Connections” by Charles R Pellegrino (2005) Amazon.com;

History of Pompeii

“It’s difficult to say who the original Pompeians were,” says archaeologist Marcello Mogetta of the University of Missouri. “But if you dig below the A.D. 79 levels — which is a real challenge because you can’t destroy mosaic floors and knock down frescoed walls — you start to see that Pompeii is a site with a very long history.”

House of the Vetti According to Archaeology magazine: As early as the tenth century B.C., there may have been a small settlement on the site, occupied by descendants of Campania’s Neolithic inhabitants. In the eighth century, when colonists from Greece settled the region, and then in the seventh century with the arrival of the Etruscans from the area to the north between the Arno and Po Rivers, Pompeii grew larger. Before the A.D. 79 eruption, the site overlooked the Sarno River and was nearly a mile closer to the coastline. But the eruption drastically altered the landscape, cutting off access to the Sarno, an important waterway for transporting both people and the plentiful agricultural products cultivated in the area’s fertile volcanic soil, and to the busy harbor that served the city. In the sixth century B.C., a fortified wall that would define the city for the next 600 years was constructed, its shape determined by the lava flow on which Pompeii sits. [Source: Benjamin Leonard and Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2019]

“Toward the end of the fifth century B.C., Samnites migrated from the mountains of south-central Italy and took over many of the region’s Greek and Etruscan towns, including Pompeii, bringing with them new gods, customs, and building styles. “The Samnites became accustomed to urban life and, from this point on, the city was a kind of melting pot of cultures and really thrived,” says Mogetta. The Samnites remained in control of the city until the late fourth or early third century B.C., when the Romans conquered the region. Two centuries later, Pompeii’s residents felt themselves to be in a strong enough position to demand full Roman citizenship. This demand was rejected, and, in 89 B.C., the Roman general and dictator L. Cornelius Sulla took over Pompeii. In 80 B.C., the city was resettled as the Roman colony of Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum, and Latin became the official tongue, replacing Oscan, the language of the Samnites. Pompeii continued to prosper and was a busy, cosmopolitan city of around 10,000 residents at the time of the eruption. During that catastrophe, thousands escaped their homes, but thousands of others would perish.

Multi-Cultural and Multi-Dimensional Pompeii

In addition to being a place where a lot of rich Romans lived and vacationed Pompeii, Ruben Montoya wrote, " also had a thriving agricultural and industrial economy. Archaeologists have found over 200 craft workshops, including tanners, textile makers, and bakers. The production of garum, a fish sauce, was a staple of the local economy. First-century Pompeii was a metropolitan place of some 15,000 people, with fast-food restaurants and a politically engaged populace. [Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

A DNA study published in November 2024 in the journal Current Biology characterizes Pompeii as a cosmopolitan, multi-cultural place. Ashley Strickland of CNN wrote: The genetic data collected during the research revealed that Pompeii was a city full of people with diverse backgrounds, the study authors said. Many descended from recent immigrants to Pompeii from the eastern Mediterranean, which reflects broader patterns of mobility and cultural exchange in the Roman Empire, said study coauthor Alissa Mittnik, group leader in the department of archaeogenetics at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and an associate in Reich’s lab at Harvard. [Source Ashley Strickland, CNN, November 9, 2024]

At the time, the Roman Empire extended from Britain to North Africa and the Middle East, while Pompeii was located next to one of the ancient world’s busiest ports, where ships regularly arrived from Alexandria in Egypt, Caitlín Barrett of Cornell University said. “What’s more, this part of southern Italy had an even longer history of international connections — the first Greek settlements in the Bay of Naples go back more than 800 years before the eruption of (Mount) Vesuvius,” Barrett said. “So it makes sense that the background and appearance of the population would have reflected this cosmopolitan history.”

Pompeii bakery The study is a great reminder of the nature of the Roman definition of family, which included everyone in the household and not just immediate members, Steven Tuck of Miami University of Ohio said. “The ethnic makeup of the deceased with so many markers from the eastern Mediterranean reminds us to be aware of the common Roman practice of enslavement and regular manumission (release from slavery) of foreigners,” Tuck said. “We know of that from Pompeii and can trace some of these people from their names in the later years of the city, but the stories told or assumed about these bodies assume a family of blood, not of slavery, marriage, manumission, adoption, and all the other ways families were created in the Roman world of Pompeii.”

Understanding the genetic diversity present in Pompeii reframes how scientists understand the city and its inhabitants, said Dr. Michael Anderson, chair of the department of classics and professor of classical archaeology at San Francisco State University. Anderson was not involved in the new study. “It helps to topple the European ‘ownership’ of the so-called ‘Classical world,’ and showcases the degree to which those are misconceptions fabricated in the 18th and 19th centuries of our own time, that do not reflect the ancient reality,” Anderson wrote. “Much of the modern interest in Pompeii has been driven by a desire to explore dramatic stories of death and destruction, to see ourselves reflected in the past, and is therefore a creation of a particular present, especially that of the time of original discovery. It is fantastic to see these old misconceptions definitively unraveled, and replaced with a much more diverse, interesting, and scientific reality.”

Ruins of Pompeii

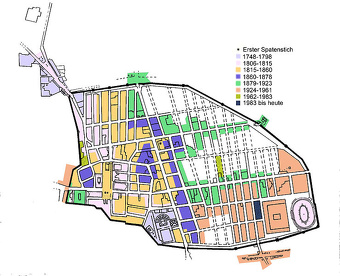

Pompeii was not discovered until the 16th century. Although Pompeii has been almost constantly excavated since the mid-eighteenth century, around one-third of the city still remains buried beneath six meters (20 feet) of volcanic debris from the A.D. 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Archaeologists have made a number of significant discoveries at Pompeii in recent years, thanks to a US$110 million project funded by the EU dubbed Great Pompeii.

The main area of ruins of Pompeii covers an area of 164 acres (about a fifth of the size of New York's Central Park) and is located within an irregular oval with a circumference of 2¼ miles. The ruins are scattered over a larger area but are not as well preserved as those of Herculaneum. Thus far about two thirds of Pompeii in this area has been excavated (115 acres exposed out of a 164). Pompeii is surrounded by about two miles of city wall and consists of the remains of official buildings, temples, sumptuous villas, 500 smaller houses (many with ground-floor stores), a large amphitheater and two smaller theaters. There are at least three Roman baths in Pompeii and many of the city's houses had gardens that took up more space than the houses themselves.

The remains of 2,000 people have been found in Pompeii. Casts are scattered around Pompeii. A couple can be seen in the caged-off on the side of the Forum. Pompeii discoveries in 2023 included a kitchen shrine adorned with serpents, a bakery, human skeletons, exquisite frescoes, and a picture of something that looked like a pizza but was not.

Art, Paintings and Artifacts from Pompeii

The artifacts unearthed at Pompeii have given archeologist valuable insights into everyday Roman life. Among the items that have been found are paintings, furniture, kitchen utensils and a bakery with 81 carbonized loaves of bread. There was lots of graffiti. Pompeii houses were mostly windowless. Their plaster walls proved t be inviting canvasses for people to express their written thoughts, some of which seem familiar today such as “Auge Loves Allotenus” and “Gaias Pumidius Dipilus was Here.”

Artistic pieces that have been unearthed include a gold bracelet of a two-headed snake that weighs half a kilogram; a silver wine goblet adorned with olives that hang off it like pearl earings; a bronze gladiator helmet sculpted with reliefs of women; a gold and silver statuette of Mercury with a small goat; and a finely-crafted necklace made of 94 ivy leaves made of gold foil. Most of these treasures are at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.

Philip M. Soergel wrote: While the eruption of Vesuvius was a terrible tragedy in the ancient world, it was a boon for modern art historians, for the lava preserved the wall decorations of the houses and the mosaics on their floors for modern excavators to discover. While wall-paintings from other sites are only isolated finds, the art from Pompeii and Herculaneum show the changes in Roman taste over three centuries. Even though Pompeii, a town of some twenty thousand inhabitants, was already past the peak of its prosperity when it was buried under the ash from Mt. Vesuvius, and so did not attract the Roman Empire's best painters, its houses present a vivid record of changing fashions. [Source: Philip M. Soergel, “Arts and Humanities Through the Eras” (2004), Encyclopedia.com]

RELATED ARTICLE: PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com

Major Features of Pompeii

The Porta Marina Entrance (about 200 meters from the train station) is the main entrance for people entering Pompeii. It is so named because it was once located at the site of the main port and marina for Pompeii. Today Pompeii is about a mile from the sea. Near the entrance is the Temple of Venus and the basilica (law court). Across the main walkway from basilica is the Sanctuary of Apollo. It contains a column with a sundial and statues of Diana and Apollo (the originals are at the archeology museum in Naples. The Forum (reached by an uphill walkway from the Porta Marina Entrance) was the main center of commercial and social activity at Pompeii. Long and narrow, it is surrounded by a colonnade. At the far end of the Forum to the left are the Forum Olitorium (Storehouses) a caged-off area of building pieces, pottery and artifacts. Inside this area are cases holding casts of some of the people who died at Pompeii.

Behind the Forum (next to Basilica) are municipal buildings. To the right of the Forum is the Comitium, Building of Eurmachia (with a carved door frame covered with images of animals, insects and scrolls), Temple of Vespian (with a frieze depicting a sacrifice) and Temple of the Temple of Public Lares.

Via dell'Abbondanza (the main thoroughfare between the Forum and the Great Plestra and Amphitheater) features political graffiti from Pompeii's last election, rude remarks about homosexuals and comments about love and conquest scribbled on the walls. One comment read, "Lovers like bees lead a honey-sweet life." Another read, "Resistus has deceived many girls."On the cobblestones one can ses large ruts made by chariot and cart wheels.

Via Stabiana has narrow, elevated sidewalks that helped Pompeii’s residents skirt the muck of its streets. The Stabian Baths (near the Lupanar on Vi. dell'Abbondanza) is a large public bath with its marble floors and stucco ceilings. The rooms include a men's bath, women's bath, dressing room, “frigidaria” (cold bath), “tepidaria” (warm bath) and “caldaria” (steam bath).

Temples at Pompeii

Temple of Jupiter (at the far end of the Forum) was mostly destroyed by an earthquake that struck 17 years before Vesuvius's catastrophic eruption. A marble relief depicts the A.D. 62 earthquake that struck Pompeii with skewed buildings and riders toppled off their horses. The Forum Baths (behind the Temple of Jupiter and the Cafeteria) features a body cast that has been chipped away reveling teeth and bone.

According to Archaeology magazine: The most important Roman deity in Pompeii was Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, and her temple, raised high on an artificial platform next to the Porta Marina (“Marine Gate”), was the city’s largest sacred site. The temple has been the subject of archaeological debate for at least the past decade.[Source: Benjamin Leonard and Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2019]

“Up until fairly recently, it was always thought that there was a direct link between the construction of the temple and the establishment of the Roman colony in the first century B.C.,” says archaeologist Marcello Mogetta of the University of Missouri, who directs current work at the site. But between 2005 and 2007, an Italian team questioned whether the first temple on the site had actually been dedicated to Mephitis, goddess of the pre-Roman Samnites, and later repurposed as a temple to Venus to honor P. Cornelius Sulla, the nephew of Pompeii’s Roman conqueror, L. Cornelius Sulla. Venus was known to be the younger Sulla’s favorite goddess.

“Although the Italian team concluded that the temple dated as far back as the late seventh century B.C., Mogetta’s ongoing excavations have now shown that while the area was settled earlier, the first temple on the spot was not built until after the establishment of the Roman colony in 80 B.C. “This debate is so important because it shows two different views of the coming of the Romans to Pompeii,” Mogetta says. “It forces us to ask ‘Is the sanctuary an ancient place of pride for a local goddess that is honored even when the Romans take over — a not uncommon occurrence — or is it a case of a Roman goddess being imposed on the local population to send a message?’ This is crucial to our understanding of the changes brought about by the Roman conquest.”

Baths of Pompeii

Public bathing was a daily leisure activity for many Pompeians, and the baths were a place for exercise, pampering, and social gatherings with friends. Pompeii’s magnificent thermal baths designed to be the jewel of Pompeii were reopened to the public in November 2019 after a painstaking excavation. Marble pillars and blocks lie where they were abandoned when the city was smothered by ash from Mount Vesuvius. The skeleton of a child who had sought shelter there was found there. “The architects "were inspired by Emperor Nero's thermal baths in Rome. The rooms here were to be bigger and lighter, with marble pools," the archaeological site's director Massimo Osanna told AFP. [Source: Ella Ide, AFP, November 25, 2019]

AFP reported: “The Central Baths lie in an area restored under the Great Pompeii Project, launched in 2012 to save the historical site after the collapse of the 2000-year-old "House of the Gladiators", which sparked outrage worldwide. "It was an emotionally charged dig," said Alberta Martellone, 43, the archaeologist who led a team of an anthropologist, geologist and vulcanologist in studying the skeleton of the child, who died aged between eight and 10. The excavation "was also moving from an architectural point of view, because it is unusual to find a building so large, with such ample rooms, in this densely built up city. It transmits a sense of grandiosity," she said.

“The city's original public bathhouses were smaller, darker and often overcrowded; the new complex would have provided a more luxurious setting for all those who could afford it -most citizens, but not slaves. Along with the baths, visitors could visit a small domus sporting a racy fresco depicting the Roman god Jupiter, disguised as a swan, impregnating the Greek mythological figure of Queen Leda. Across the cobbled Via del Vesuvio, the striking House of the Golden Cupids reopened after work on its mosaic floors.

Stabian Baths, the oldest of five public bath complexes in Pompeii were built sometime after 125 B.C. and occupied a prime location at the intersection of two main thoroughfares. According to Archaeology magazine: Around the turn of the first century A.D., the baths were supplied for the first time with running water from the public aqueduct. Water had previously come from a well that supplied a reservoir on the complex’s roof. “This caused a major revolution in bathing culture,” says archaeologist Monika Trümper of the Free University of Berlin, who leads ongoing excavations of the baths. Renovations of the Stabian Baths at the time introduced amenities such as a cold-water pool, a hot bath, running fountains, and heated walls and floors in the complex’s warm and hot rooms. [Source: Benjamin Leonard and Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2019]

“Rebuilding efforts undertaken after the earthquake that struck Pompeii in A.D. 62 made the Stabian Baths an even more luxurious space. In addition to necessary repairs, Trümper explains, the complex was again completely remodeled, enlarged, and embellished with new decoration to match the state-of-the-art standards set by the Central Baths, which were under construction nearby. A swimming pool and decorative fountains were added, along with new shops on the building’s street front. “The earthquake was the chance to rebuild the city,” Trümper says, “and to modernize bathing facilities in grand style.”

Theaters at Pompeii

Amphitheater (east end of Pompeii) was large enough to accommodate 40,000 people. It was one of the first to be built specially for gladiator contest. Among the gladiators that fought there was Spartacus. A variety of helmets and weapons have been unearthed under the gladiator’s barracks along with the remains of a wealthy woman wearing lots of expensive jewelry, raising speculation that perhaps she died during the eruption while visiting a gladiator lover.

Large Theater (across Via dell'Abbondanza from the Stabian Baths) has seats for 5,000 spectators. Built in the 2nd century B.C., it was used for various kinds of entertainment, including gladiator battles and dramas. The gladiator barracks lie behind the stage. To one side of the Large Theater is the Little Theater, which staged dramas and dance performance. On the other side is the Triangular Forum and a Doric Temple. On the way to Via dell'Abbondanza are two excellent, well-preserved houses — the House of Secindu and the House of Meander — both with good frescoes.

Pompeii Gardens, Horses and Stables

According to Archaeology magazine: Pompeii’s residents spent a great deal of time socializing in the city’s lush public and domestic gardens. “What’s remarkable about Pompeii is the enormous variety of gardens, and the extent to which Pompeians lived both inside and outside,” says archaeologist Kathryn Gleason. “Pompeians’ devotion of valuable real estate to gardens is noteworthy.” [Source: Benjamin Leonard and Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2019]

One of the largest private gardens could be found at the back of the Casa della Regina Carolina, an opulent dwelling named in the nineteenth century after Caroline — the queen of Naples and sister of Napoleon Bonaparte — who visited during its initial excavation. Celebrated for its vibrant decoration in the years after its discovery, the house was largely forgotten as its wall paintings faded. Returning to the property after more than a century, a team of archaeologists including Gleason and Caitlín Barrett of Cornell University and Annalisa Marzano of the University of Reading now hopes to learn about the garden’s original landscaping, as well as find traces of religious activity that might have taken place there. In particular, they plan to explore the house’s two garden shrines, where nineteenth-century excavators found such objects as a marble incense burner and a statuette of the goddess Diana. “These shrines provide us with sites where ritual activity took place,” says Barrett. “The material culture can hopefully speak to the performance of those rituals.”

Ruben Montoya wrote: Less than half a mile outside the northern walls of ancient Pompeii, in a suburb called Civita Giuliana, archaeologists found a stable with three horses preserved by the eruption. One of them allowed for the first ever plaster cast of a complete horse killed by Vesuvius. Separate from the Great Pompeii Project, this 2018 excavation was prompted by a police investigation. Grave robbers had built tunnels into the site to steal artifacts to sell on the black market. The illegal excavations damaged two of the horses and other artifacts, along with ancient walls and plasterwork, but one horse remained untouched. [Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

Archaeologists secured and excavated the site, which revealed a richly frescoed villa with an attached stable and cultivated lands. Analysis of the horses revealed them to be in good health and of large size. Based on their physical condition and the remains of a bronze-plated military saddle, they were probably purebreds, a sign of high social status. These horses were likely bred for local events, such as races, circuses, and parades. (The horses were found wearing harnesses — possibly to flee the eruption.)

Brothels at Pompeii

Lupanar (a couple of blocks away from the Forum) is an ancient brothel famous for its erotic frescoes and inscriptions. Each of the prostitutes worked in a stall with a stone platform-style bed (and today often a cat). Above the stalls are erotic frescoes that reportedly described the specialty of the prostitute who worked inside. Taverna Lusoria is a gambling house frequented by both men and women. Inscription mark loans given by the owner to his patrons.

There were at least 25 brothels in Pompeii. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Excavations at Pompeii uncovered a number of brothels, the most famous of which — the Lupanare (wolf’s den) — was built specifically for this purpose. This wasn’t the case with all ancient brothels which, as Professor Sarah Bond has written in Trade and Taboo, could set up shop in inns, taverns and even mills. The Lupanare contained ten rooms, each of which was furnished with a stone bed and mattress that were separated from an antechamber by a curtain. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, 2017]

Ben Gazur wrote in Listverse: In most societies, prostitution has been, if not illegal, then at least looked on as something deeply shameful. For the Romans, this was not the case. The Lupinar in the ruins of Pompeii gives us a peek into the world of the Roman brothel. Instead of hidden away in a dank alley, it proudly asserts the sort of business one could do inside. Graffiti tells people what to expect from the various women on offer. Once inside, several graphic images help those with less imagination or the illiterate understand just what they were buying.[Source Ben Gazur, Listverse, January 7, 2017]

Some places looked like they should have been brothels but weren't. The he House of the Vetti (on V. della Fortuna) is one of the most popular villas at Pompeii. The Ixon Room in the villa looks like a small art gallery. There are delightful murals with cherubs performing tasks like forging, goldsmithing and making weapons. The biggest draw are the erotic frescoes and statues. A fresco beside the entrance to the villa shows the god of fertility Priapus, whose penis is so large it is held up by a string. Off in a side room to the right of the Priapus entrance is statue of Priapus with his penis erect and erotic frescoes of couples having sexual intercourse sitting down and in other positions. In Roman times, rooms with erotic art were generally only for men and their concubines.

See Separate Article: PROSTITUTES AND BROTHELS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Fast Food Joints at Pompeii

Thermopolium of Asellima is a bar where bronze cups, lamps and petty cash were found. Outside on a wall are scrawled the names of three women who presumably entertained guests in the cubicles upstairs; as well as the names of favored candidates in an upcoming election.

Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker: A “thermopolium, which opened to visitors in August 2021, is a delight. A masonry counter is decorated with expertly rendered and still vivid images: a fanciful depiction of a sea nymph perched on the back of a seahorse; a trompe-l’oeil painting of two strangled ducks on a countertop, ready for the butcher’s knife; a fierce-looking dog on a leash. The unfaded colors — coral red for the webbed feet of the pitiful ducks, shades of copper and russet for the feathers of a buoyant cockerel that has yet to meet the ducks’ fate — are as eye-catching now as they would have been for passersby two millennia ago. (Today, they are protected from the elements and the sunlight by glass.) [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, November 22, 2021]

“It turns out that few of Pompeii’s more straitened residents had a place at home to cook. “Rich people had kitchens in their houses, and banquet rooms and gardens,” Pompeii's director Gabriel Zuchtriegel told me, as we walked around the thermopolium. “But most inhabitants didn’t live in such places — they had small apartments, or even one-room flats. During the daytime, their place was a shop or a workshop, and at night the family would just close up the front and sleep there. And, when they could afford it, they would come here and have a warm meal, and take their plate and eat it on the street.” Zuchtriegel took a step back, toward a fountain; it would have provided fresh water for drinking, bathing, or cooling down. “It was life on the street, as today we can still see in Naples,” he said.

thermopolium that opened in 2021

“The thermopolium on the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento is far from unique — through the centuries, about eighty such establishments have been identified in Pompeii. But archeological science is now more evolved, Zuchtriegel told me, and at the new site scholars “can use modern technologies and methodologies to analyze what was inside the pots.” Fragments of duck bone were discovered in one of the containers, which are known as dolia, suggesting that the paintings of ducks served not just as decoration but as advertising. In other dolia, scholars found traces of cooked pig; what appears to be a stew of sheep, fish, and land snails; and crushed fava beans. A book of recipes attributed to Apicius, a celebrated Roman gourmet from the first century A.D., explains that “bean meal” can be used to clarify the color and flavor of wine.

These near-invisible remains of foodstuffs do not just provide information about the diet of Pompeii’s working classes. According to Sophie Hay, a British archeologist who has worked extensively at Pompeii, they also shed new light on the rhythms of civic life. “Up until this bar was excavated, people who study these things have gone around believing that the dolia contained only dry foodstuffs,” she told me. “There are Roman laws that said bars shouldn’t serve this kind of warm food, like hot meat, so we’ve been guided by the classical sources. Then, suddenly, there is this one bar that is definitely serving hot food. And is it the only bar in the Roman world to have done this? Unlikely. So that is huge.” A new story appears to be emerging from the lapilli: of a cunning bar owner who reckons that an authority from distant Rome isn’t likely to shut down his operation, or who is confident that the local authorities — the kind of Pompeiians who live in grand houses — will turn a blind eye to an illegal takeout business that keeps their less affluent neighbors fed with cheap but tasty fish-and-snail soup.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN RESTAURANTS, FOOD STALLS AND FAST FOOD europe.factsanddetails.com

Cemeteries in Pompeii

According to Archaeology magazine: One of the most interesting cemeteries lining the well-traveled roads connecting Pompeii with the surrounding area was first identified more than 100 years ago just outside the Porta Nola, the gate leading to the city of Nola. “The Porta Nola necropolis is fascinating because it gives us the opportunity to look at a wide section of society,” says archaeologist Stephen Kay of the British School at Rome, who, alongside Llorenç Alapont of the European University of Valencia and Rosa Albiach of the Valencia Museum of Illustration and Modernity, leads a team that has been reinvestigating the burial ground. “We have very high-status monumental tombs such as the one belonging to Marcus Obellius Firmus, a member of one of Pompeii’s richest families, and a uniquely Pompeian style of semicircular tomb belonging to a woman named Aesquillia Polla,” Kay says. [Source: Benjamin Leonard and Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2019]

“Excavations at the Porta Nola have, in addition, uncovered simple cremation burials of poorer Pompeians that Kay’s team has now associated with a series of Greek names inscribed on the city walls. The necropolis also contains four graves of members of the Praetorian Guard, elite soldiers who served as the emperor’s household troops and bodyguards. Each grave was marked by an inscribed marble slab called a columella, and contains a selection of artifacts. The guards’ burials were first excavated in the 1970s, and the team has now uncovered the ceramic cremation urns containing all the soldiers’ remains.

Another notable group of Pompeii’s dead is also represented at the Porta Nola: 15 people who were killed by the eruption and preserved in plaster casts made of their bodies during the twentieth-century excavations. Kay and his team are now examining the preserved skeletons inside the casts to see what they might be able to tell about the sort of people who lived and worked in the Porta Nola neighborhood. Says Kay, “These people are an important part of the city and its history of death.”

Tombs in Pompeii

The mausoleum at Porta Stabia is located at Pompeii’s southern gate. The marble tomb, built shortly before the volcano’s eruption, has the longest funerary epigraph ever found — over 13 feet — revealing much about Pompeian life. [Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

The remains of a man identified as Marcus Venerius Secundio were unearthed in a tomb east of Pompeii, where a necropolis is close to one of the city gates. Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker: “Unusually for an adult burial, the deceased had been embalmed rather than cremated, and the body was so well preserved that hair and even part of an ear were intact. [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, November 22, 2021]

“Secundio, Zuchtriegel explained, was a freedman, having formerly been a public slave — essentially, a municipal worker owned by the city. “Of course, nobody wanted to be a slave — it was very humiliating to be the property of someone,” Zuchtriegel said. “On the other hand, if you were a very poor freedman you were less well off than a household slave, some of whom were educators of the children of rich people, or secretaries who were part of the team that carried on the business of the owner.”

It is unknown how Secundio gained his freedom, but historical records indicate that a public slave could raise funds to buy himself out of servitude. Evidently, Secundio ascended within Pompeiian society, becoming an augustalis, or a priest in the imperial cult — one of the few high-ranking positions open to men who were not freeborn. According to the funerary inscription on his tomb, Secundio was a patron of the arts, paying for ludi — musical or theatrical events that were performed in Latin and, significantly, in Greek. “This is the first time we have this direct evidence of Greek plays in Pompeii,” Zuchtriegel told me. Scholars had hypothesized, based on evidence in wall paintings and graffiti, that such events took place, but the inscription provides exciting confirmation.

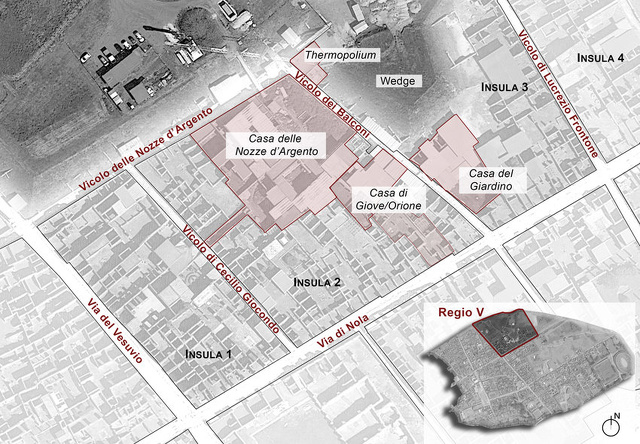

Regio V

Regio V, Pompeii’s fifth region, where the the first significant excavations at Pompeii in decades began in the early 2010s. Beginning at the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento (Street of the Silver Wedding), the excavation have yielded two houses — the House of the Garden and the House of Orion — as well as beautifully-colored frescoes, mosaics of mythological figures, skeletons with stories to tell, a wooden bed, coins, amulets, and a stable of a wealthy landowner with three top-quality horses, one with bronze-plated wooden horns on the saddle and an iron harness with small bronze studs. Excavations in 2018 to stabilize walls in Region V revealed the Alley of the Balconies, a unique alley area where different social classes mixed among modest homes and grand houses with four large second-floor balconies, preserved because they collapsed on a bed of lapilli, or soft pumice, from the volcano’s eruption. One terrace still had amphorae for wine and oil on it. [Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker: “For many years, the formal excavations stopped just past the House of the Silver Wedding. Since 2018, restoration work has been under way in Regio V to reshape and shore up the escarpment. Made up of impacted ash and lapilli, or pebbles of pumice, it had become increasingly vulnerable to collapse, especially after heavy rain. (When chunks of the escarpment broke off, artifacts and structures buried inside it were often obliterated.) Collapses aside, the weight of the unexcavated land in Regio V put the adjacent excavated area at risk by exerting immense pressure on exposed walls, some of which date to the first or second century B.C. The fragile escarpment threatened to make a ruin of the ruins. [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, November 22, 2021

“Through a careful combination of archeology and engineering, the escarpment has been reshaped into a more gradual slope, with an exposed surface of rocky fragments secured by sturdy mesh. In order to lessen the gradient, it has been necessary to unearth a small area of previously buried streets and structures. In recent decades, most archeological excavations at Pompeii have been of layers that predated the first-century city — digging down to reveal, for example, that several of the town’s temples were built on structures that dated to the sixth century B.C. The new excavations in Regio V — conducted with the latest archeological methods, and an up-to-the-minute scholarly focus on such issues as class and gender — have yielded powerful insights into how Pompeii’s final residents lived and died. As Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, a professor emeritus at Cambridge University and an authority on the city, told me, “You only have to excavate a tiny amount in Pompeii to come up with dramatic discoveries. It’s always spectacular.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024