Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory / Life, Homes and Clothes

HOUSES AT POMPEII

Like most urban areas, ancient Pompeii had residences of all types, including smaller city houses, sprawling villas, and multistory apartment buildings. Ruben Montoya wrote: One of the most distinctive features of a Pompeian house is the lararium, a shrine to the household gods. Called Lares, these deities protected the family, and statues of them were often placed in a special niche for worship. In 2018 archaeologists unearthed a semi-enclosed courtyard in Region V, with one of the finest examples of a lararium ever discovered in Pompeii. The niche for the shrine is flanked by painted twin images of Lares. Painted on the wall beneath the niche are two large serpents, symbolizing prosperity and good luck, and a pedestal topped with food and offerings. On the floor rests a small stone altar that still bears traces of burnt offerings to ensure the goodwill of the Lares. The space is decorated to resemble a magnificent garden. Birds flit among the trees, while a peacock seems to stroll along the ground, blending in with painted plants and real ones that once grew in a flower bed along the wall. A dynamic hunting scene was painted on a vibrant red wall. A massive black boar is being pursued by other animals, who are close to bearing down on it. [Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

Pompeii is most famous for its many fine villas owned by wealthy Romans. According to Archaeology magazine: Few of Pompeii's homes were as grand as the Villa of Diomedes. “The Villa of Diomedes combines the characteristics of a city dwelling where a wealthy family lived and received guests, and all the attractions of a seaside villa spread over 40,000 square feet with a panoramic view of the Bay of Naples,” says archaeologist Hélène Dessales of the École normale supérieure of Paris. It was also one of the first properties in Pompeii to be excavated when, between 1771 and 1775, Francesco La Vega, an engineer serving Charles of Bourbon, the king of Naples, explored the property.[Source: Benjamin Leonard and Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2019]

La Vega kept careful records of his work, and Grand Tour artists drew and sold scenes of the villa. Paradoxically, though, explains Dessales, while it has been one of the most widely represented buildings in Pompeii for more than 250 years, the Villa of Diomedes’ 2,000-year-plus history from its foundation through A.D. 79 to the present has never been comprehensively understood. For the past seven years, Dessales has supervised an international project that has taken more than 25,000 new photographs and used software to combine these modern images with more than 350 archival ones showing the villa at different times since its discovery. They have created the first highly detailed 3-D model of a residential property in Pompeii.

RELATED ARTICLES:

POMPEII: HISTORY, BUILDINGS, INTERESTING SITES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ERUPTION OF VESUVIUS IN A.D. 79: EFFECTS, EARTHQUAKES AND PLINY THE ELDER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com

POMPEII ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POMPEII VICTIMS: THEIR LIVES, CASTS, DEATHS AND DNA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM VICTIMS: THEIR LIVES, DEATHS AND VAPORIZATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, BUILDINGS europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (1996) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Villas: The Essential Sourcebook” Ancient Roman Villas: The Essential Sourcebook” by Guy P. R. Métraux (2025) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pompeii”, Illustrated, by Joanne Berry (2007) Amazon.com;

“Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Paul Roberts Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: An Archaeological Guide by Paul Wilkinson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Inside Pompeii”, a photographic tour, by Luigi Spina (2023) Amazon.com;

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

“Water Displays in Domestic Spaces across the Late Roman West: Cultivating Living Buildings” by Ginny Wheeler (2025) Amazon.com;

“Roman Gardens” by Anthony Beeson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Alison E. Cooley (2013) Amazon.com;

“Herculaneum: Italy's Buried Treasure” by Joseph Deiss (1989) Amazon.com;

“The Library of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by David Sider (2005) Amazon.com;

“Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by Kenneth Lapatin (2019) Amazon.com;

Famous Houses in Pompeii

Pompeii houses are usually named after prominent paintings or sculptures or other artifacts. The House of the Moralist at Pompeii is so named because the owner wrote rules of etiquette for his neighbors and visitors on the walls of his house, including “Let water wash your feet clean” and “Take care of our linens." The House of the Tragic Poet (on Via dell'Abbondanza near the Amphitheater) features a fine entrance mosaic with a snarling dog and a sign that says "Cave Canem" (“Beware of the dog”). The House of Venus (on Via dell'Abbondanza near the Amphitheater) features wonderful frescoes and modern gardens planted like Roman gardens.

House of the Surgeon is so no named, for example, because a bunch of doctor instruments were found there. The House of Chaste Lovers features a fresco of, yes, chaste lovers. Many frescoes can be viewed at Pompeii. It is worth wandering around aimlessly for a while on your and checking out the frescoes in the villas off the main tourist circuit.

House of Faun (nearby on V. della Fortuna) is named after a bronze of a dancing faun that was found here along with a large floor mosaic that reads Have (Welcome). The famous Alexander the Great mosaic was also found here. Near the House of Faun off of V. della Fortuna are the House of the Labyrinth, the House of the Ancient Hunt and an ancient bakery. House Marcus Lucretius Fronto (several blocks east of the House of the Vetti) features a garden mural that depicts a hunt scene with bears, boars, and snakes in addition to a lion attacking a bull and a tiger pursuing a deer.

House of Chaste Lovers was opened the late 2000s. It is named after a fresco of a couple in a gentle embrace. In antiquity the house was both a residence and a commercial enterprise for a wealthy entrepreneur. A bakery has been identified by the presence of ovens. Pollen analysis revalued that reed trellises separated geometrically-shaped beds of roses, juniper and ferns. The triclinium (dining room) was painted with banqueting scenes, including the lovers. A depiction of a drinking game in The House of Chaste Lovers in Pompeii shows one person still drinking while another is slumped over a couch, defeated.

House of the Silver Wedding is located on Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento — the Street of the Silver Wedding — on the boundary of Regio V, Pompeii’s fifth region. According to The New YorkerL It was uncovered in the late nineteenth century and named, in 1893, in honor of the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of the Italian monarch, Umberto I, and his wife, Margherita of Savoy. The spacious house, which is believed to have belonged to a Pompeiian bigwig named Lucius Albucius Celsus, included a salon fitted with a barrel-vaulted ceiling supported by columns of trompe-l’oeil porphyry, and an atrium, decorated with frescoes, that scholars regard as the finest of its kind in the city.[Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, November 22, 2021

House of Maximus Obellius Firmus belonged to one of Pompeii’s most prominent citizens in the period before the eruption and demonstrates the Pompeiian fascination with Greek culture. According to the The New Yorker: An interior garden was surrounded by a peristyle — a rectangular perimeter of covered columns — which was popular in classical Greece. “There is an attempt to transform a traditional Roman house into a Greek space,” Pompeii director Gabriel Zuchtriegel said. “You could be here in the middle of Pompeii, and feel like you were in a different space.”

Houses in Pompeii Victims Were Found

Ashley Strickland of CNN wrote: Multiple people were found in the Villa of the Mysteries, and it was clear they died during different points of the eruption. The bodies of two adults, thought to be women, and a child were discovered where they fell on the home’s lower floor, while six more sets of remains ended up in overlaying ash deposits in the same home, suggesting they survived the first wave of the eruption, only to die later. One person was found alone in a room with a whip and five bronze coins and wore an engraved iron ring bearing a female figurine. The man was thin and about 6 feet (1.85 meters) tall, and based on the traces of his clothes, he was likely the villa’s custodian who remained at his post until the end, the researchers said. [Source Ashley Strickland, CNN, November 9, 2024]

The House of the Golden Bracelet, a terraced structure decorated with colorful frescoes, was named for an adult found wearing the item and with a child astride on their hip. Next to them was another adult, presumed to be the child’s father. All three were found at the foot of a staircase that led out to a garden, while a second child was discovered a few meters away, possibly separated from the rest as they tried to escape to the garden.

The House of the Cryptoporticus was named for the home’s underground passageway with openings that ran along three sides of the property’s garden. The home’s walls were decorated with scenes inspired by Homer’s “The Iliad.” While nine people were found in the garden in front of the home, casts could only be made for four of them.

The remains of two individuals found in Casa del Fabbro, or the House of the Craftsman, which was first discovered in 1933. One was a man in his late 30s at the time of his death, while the other set of remains belonged to a woman, who was older than 50.

House of the Golden Bracelets

The three-story House of the Golden Bracelet on the Vicolo del Farmacista was one of the most opulent in Pompeii.Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: its walls covered with vibrant frescoes depicting theatrical scenes and imitating expensive marble paneling, its floors paved with intricate black-and-white geometric mosaics. At the rear of the house lay a verdant garden with a splashing fountain and quiet pools, its natural beauty echoed by wall paintings depicting oleander, viburnum, arbutus, bay, palm trees, irises, roses, daisies, and poppies, home to doves and house sparrows, a swallow, a golden oriole, and a jay. From the terrace was a view of the sea, whose breezes cooled the house during hot Mediterranean summers. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2016]

A wall painting from the House of the Golden Bracelet in Pompeii dating to the 1st-century B.C. or the 1st-century A.D. depicts a garden filled with dozens of local species of plants and birds, a birdbath, herms supporting plaques showing sleeping women, and theater masks.

A bracelet weighing more than a pound, composed of a two-headed snake holding a medallion depicting the moon goddess Selene, gives the House of the Golden Bracelet its name. In 1974 four people were discovered in voids under a flight of stairs leading to the House of the Golden Bracelet’s garden. Using the technique pioneered by Fiorelli, casts were made of the bodies, revealing them to be a man, a woman, and two small children who had likely died on the eruption’s second day, killed either by the collapse of the staircase or by the pyroclastic flow.

House of Pansa in Pompeii

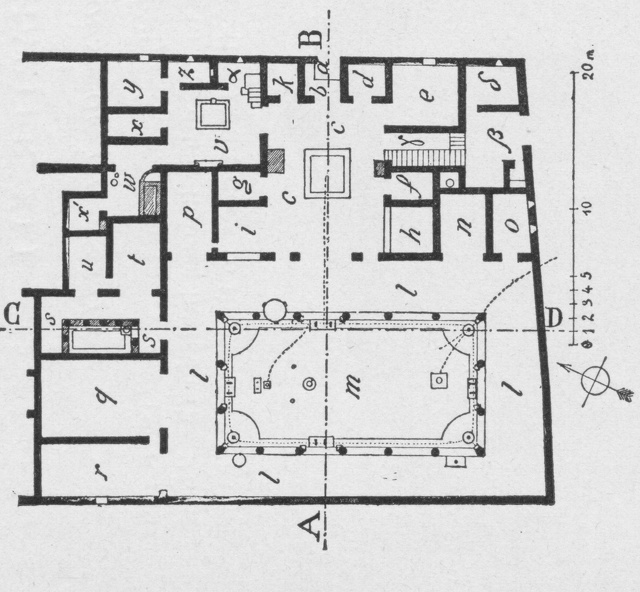

The House of Pansa presumably belonged to a wealthy and influential man. It occupied an entire block; it faced a little east of south. Most of the rooms on the front and sides were rented out for shops or stores or apartments; in the rear was a garden. The rooms that did not belong to the house proper are shaded in the plan given. The vestibulum is the open space between two of the shops. Behind it are the ostium, with a figure of a dog in mosaic, opening into the atrium. The atrium had three rooms on each side, the alae in the regular place, the impluvium in the middle, the tablinum opposite the ostium, and the passage on the eastern side. The atrium is of the Tuscanicum style, and is paved with concrete; the tablinum and the passage have mosaic floors. From these, steps lead down into the peristylium, which is lower than the atrium, measures 65 by 50 feet, and is surrounded by a colonnade with sixteen pillars in all. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

There are two rooms on the side next the atrium. One of these has been called the bibliotheca, because a manuscript was found in it, but its purpose is uncertain; the other as possibly a dining-room. The peristylium has two projections, much like the alae, which have been called exedrae; it will be noticed that one of these has the convenience of an exit to the street. The rooms on the west and the small room on the east cannot be definitely named. The large room on the east (T) is the main dining room; the remains of the dining couches are marked on the plan.

The kitchen is at the northwest corner with the stable next to it; off the kitchen is a paved yard with a gateway from the street by which a cart could enter. East of the kitchen and yard is a narrow passage connecting the peristylium with the garden. East of this are two rooms, the larger of which is one of the most imposing rooms of the house, 33 by 24 feet in size, with a large window guarded by a low balustrade, and opening into the garden. This was probably an oecus. In the center of the peristylium is a basin about two feet deep, the rim of which was once decorated with figures of water plants and fish. Along the whole north end of the house ran a long veranda, overlooking the garden in which was a sort of summer house. The house had an upper story, but the stairs leading to it are in the rented rooms, suggesting that the upper floor was not occupied by Pansa’s family. |+|

“Of the rooms facing the street it will be noticed that one, lightly shaded in the plan, is connected with the atrium; it was probably used for some business conducted by Pansa himself , possibly with a slave or a freedman in immediate charge of it. Of the others the suites on the east side (A, B) seem to have been rented out as living apartments. The others were shops and stores. The four connected rooms on the west, near the front, seem to have been a large bakery; the room marked C was the salesroom, with a large room opening off it containing three stone mills, troughs for kneading the dough, a water tap with sink, and an oven in a recess. The uses of the others are uncertain. The section plan represents the appearance of the house if all were cut away on one side of a line drawn from front to rear through the middle of the house. It is, of course, largely conjectural, but it gives a clear idea of the general way in which the dividing walls and roof must have been arranged.” |+|

House of Pansa plan

Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii

The Villa of Mysteries (outside of Pompeii in a suburb) is regarded as the best preserved villa from the ancient world. Discovered in 1909 and completely excavated by 1929, it contains what have been described as the “the best preserved pictorial cycle of antiquity.” Ashley Strickland of CNN wrote: The Villa of the Mysteries gets its name from a series of frescoes, dating back to the first century B.C., that depict a ritual dedicated to Bacchus, the god of wine, fertility and religious ecstasy, according to the study authors. The villa included its own winepress, common for wealthy families at the time. After being closed for two years, all 70 rooms of the Villa of the Mysteries, reopened in 2015, revealing to the public for the first time the astonishing results of an extensive restoration and conservation project. [Source Ashley Strickland, CNN, November 9, 2024]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: As modern visitors to Pompeii walk along the miles of ancient streets paved with original stones, through the forum where temples and warehouses still stand, past a bakery with its enormous grindstone, and inside the bars, shops, houses, and brothels that still line the carefully planned streets, it’s easy to believe that the city appears almost exactly as it did on the day Mount Vesuvius erupted almost two millennia ago. Nowhere does this seem to be more true, perhaps, than in the Villa of the Mysteries. Ancient mosaics still decorate the villa’s original floors, and stunning frescoes are still visible on the walls they have always covered. The villa stands in high contrast to many of the city’s homes where lavish decoration was lost to looters or removed to private collections and museums across the world beginning soon after the city’s mid-eighteenth-century discovery. But when the decision was made very early on to leave the paintings in place. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2014]

Built just outside one of Pompeii’s main gates in the first half of the second century B.C., the Villa of the Mysteries covered about 40,000 square feet and had at least 60 rooms. In A.D. 79, the house was already more than two hundred years old and had likely had several different owners, been redecorated, and been heavily repaired, particularly after a large earthquake struck Pompeii in A.D. 62, damaging many buildings and necessitating repairs all over the city. At various times the villa functioned, as many ancient Roman estates did, as both luxury home and working farm. There were areas for pressing grapes into wine, several large kitchens and baths, gardens, shrines, marble statues, and all the spaces necessary for a wealthy patron to welcome guests for both business and pleasure. Many rooms were covered in frescoes, including a bedroom with simple black walls, an atrium decorated with panels painted to resemble stone, several rooms that contain fantastical architecture and landscapes, and scenes of sacrifices, gods, and satyrs.

“The most spectacular frescoes, painted in the mid-first century B.C., were found less than a week after excavations began, in an approximately 15-by-15-foot space that was likely used as a dining room. There, against a vivid red background, more than two dozen life-size figures engage in what has been variously interpreted as a play or pantomime, a bride’s preparations for her wedding, or, most often, an initiation ritual into the mystery cult of Dionysus. (In contrast to recognized public religion and worship, in the Greco-Roman world the mystery cults required the worshipper to be initiated.)

Layout of the Villa of the Mysteries

James W. Jackson wrote in the Villa of Mysteries website: “This villa, built around a central peristyle court and surrounded by terraces, is much like other large villas of Pompeii. However, it contains one very unusual feature; a room decorated with beautiful and strange scenes. This room, known to us as "The Initiation Chamber," measures 15 by 25 feet and is located in the front right portion of the villa. [Source: James W. Jackson, Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii website]

“The term "mysteries" refers to secret initiation rites of the Classical world. The Greek word for "rite" means "to grow up". Initiation rites, then, were originally ceremonies to help individuals achieve adulthood. The rites are not celebrations for having passed certain milestones but promote psychological advancement through the stages of life. Often a drama was enacted in which the initiates performed a role. The drama may include a simulated death and rebirth; i.e., the dying of the old self and the birth of the new self. Occasionally the initiate was guided through the ritual by a priest or priestess and at the end of the ceremony the initiate was welcomed into the group.

“The chamber is entered through an opening located between the first and last scenes of the fresco The fresco images seem to part of a ritual ceremony aimed at preparing privileged, protected girls for the psychological transition to life as married women. The frescoes in the Villa of Mysteries provide us the opportunity to glimpse something important about the rites of passage for the women of Pompeii. But as there are few written records about mystery religions and initiation rites, any iconographic interpretation is bound to be flawed. In the end we are left with the wonderful frescoes and the mystery. Nevertheless, an interpretation is offered, see if you agree or disagree.

“At the center of the frescoes are the figures of Dionysus, the one certain identification agreed upon by scholars, and his mother Semele (other interpretations have the figure as Ariadne). As he had been for Greek women, Dionysus was the most popular god for Roman women. He was the source of both their sensual and their spiritual hopes.

RELATED ARTICLE: PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com

Villa de Misteri

House of the Vettii

The House of the Vetti (on V. della Fortuna) is one of the most popular villas at Pompeii. Located in the wealthiest part of Pompeii, it likely belonged to two former slaves who became rich through the wine trade and is famous for its frescoes and architecture. Discovered and restored in 1894, the House of the Vettii, was the first Pompeii domus to be found with all the frescoes and furnishings in situ.

In January 2023, the opulent villa was formally unveiled after 20 years of restoration. “The House of the Vetti is like the history of Pompeii and actually of Roman society within one house,” Pompeii’s director, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, told journalist during a visit to the Cupid Rooms. “We’re seeing here the last phase of the Pompeian wall painting with incredible details, so you can stand before these images for hours and still discover new details. So, you have this mixture: nature, architecture, art. But it is also a story about the social life of the Pompeiian society and actually the Roman world in this phase of history," Zuchtriegel added.

Francesco Sportelli of Associated Press wrote: The Vettis were two men — Aulus Vettius Conviva and Aulus Vettius Restitutus. In addition to having part of their names in common, they shared a common past — not as descendants of noble Roman families accustomed to opulence, but rather, Pompeii experts say, almost certainly, as once enslaved men who were later freed. It is believed that they became wealthy through the wine trade. While some have hypothesized the two were brothers, there is no certainty about that. [Source: Francesco Sportelli, Associated Press, January 10, 2023]

The House of the Vettii boasts a colonnaded garden surrounded by 18 columns and filled with sculptures, fountains and plants. Ornamental marble baths and tables surround the garden. The garden’s water pipes were replaced allowing the fountains to spurt again. The home also has a kitchen, a servants quarters and a room likely used for prostitution, officials said. Pompeii’s architect director of restoration work, Arianna Spinosa, called the restored home “one of the iconic houses of Pompeii. The residence "represents the Pompeiian domus par excellence, not only because of the frescoes of exceptional importance, but also because of its layout and architecture.” First unearthed during archaeological excavations in the late 19th century, the domus was closed in 2002 for urgent restoration work, including shoring up roofing. After a partial reopening in 2016, it was closed again in 2020 for the final phase of the work, which included restoration of the frescoes and of the floor and colonnades.

RELATED ARTICLE: PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com

Rooms in the House of Vetti

Room r is in the most northwestern corner of the house. It has a large entranceway that opens out onto the courtyard (room m). Inside of the room, a variety of assorted remains have been found including pieces of bronze and marble statues. Due to the assortment of artifacts discovered in the area it is possible that the room might have become a storage area for items in need of repair. As is the case in another Pompeian house, Casa degli Amorini Dorati, pieces of statues were found in a room off the garden indicating the room had become a place to store broken statues that were once in the garden or elsewhere in the house. [Source: MIT Education]

Room q is located off of the courtyard to the north, with an exit on its southern side. There is an entrance to room r in the southwestern corner. Of the ornamentation, most is in black and red with following the Forth Style . A variety of figures adorn the walls, painted on plaster, including cupids. The side panels also featured heroic figures such as Poseidon Apollo and Daphne. In general the room is decorated by red panels separated by black columns. Above the panels which featured wall paintings were varieties of architectural elements against a white wall. Amongst these included comic figures of writers. Towards the middle of the wall is a thick black stripe featuring satyr and bacchante on one wall and Amazons on another. On a strip below the panels there are many cupids and psyches depicted carrying out daily activities. Some are also participating in common leisure activities. Quite fascinating is the series of scenes where cupids were going about the process of making oil. The central panels have been noted to be missing but Mau notes that another panel from the northern wall had been repaired by using iron brackets, similar to what had been done in another room. Mau considered this as an indication that the panels were incredibly important as they received such special attention. Mau suggests that the room could have been used for dining or as a sitting room.

Room s was a small garden to the north of the courtyard. It opened to the courtyard on its southern wall as well as rooms u and t on its eastern wall. Fourth Style decoration was sued on the northern and eastern walls, featuring plants.

Room u, which Mau interpreted as a cubiculum was to the east of room s and to the north of room u. It opened to room s on its western wall and with a doorway to room t on its southern wall. Fourth Style was again used in decorating walls though making use of reds and yellows, surrounded by borders and cupids.

Room t is located north of the courtyard but did not have a southern exit. The room was open to room s on its western side, and to room u through a door on its northern side. The room was decorated in Fourth Style with panels. The central panel features Heracles and Auge, and Achilles and Skyros. Mau estimates that the room was a triclinium.

Leda and the Swan at the Casa di Leda

Casa di Leda

The exceptionally luxurious House of Leda in Pompeii is renowned for its sensual frescoes, notably the famous depiction of Leda and the Swan and a satyr and nymph associated with the cult of Dionysus on an atrium wall. The Leda and the Swan fresco portrays Jupiter, transformed into a swan, attempting to seduce Leda, the queen of Sparta. Located in a cubiculum next to a corridor adorned with the figure of Priapus, this fresco epitomizes the Fourth Style, which also adorns the now-collapsed ceiling. The house also features frescoes of Narcissus and Mercury, enriching it with layers of mythology and culture.

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The entrance hall features the welcoming image of the fertility god Priapus, weighing his prodigious membrum virile on a scale like a prize-winning zucchini. Dominating a wall of the atrium is a stunning fresco of the hunter Narcissus leaning languidly on a block of stone while contemplating his reflection in a pool of water. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, September 2019]

Embellished with a tracery of garlands, cherubs and grotesques, the bedroom of the same house contains a small, exquisite painting depicting the eroticized myth of Leda and the Swan. Half-nude, with dark eyes that seem to follow the observer, the Spartan queen is shown in flagrante with Jupiter disguised as a swan. The king of the gods is perched on Leda’s lap, claws sunk into her thighs, neck curled beneath her chin. Osanna says the explicit fresco is “exceptional and unique for its decisively sensual iconography.” He speculates that the owner of the house was a wealthy merchant, perhaps a former slave, who displayed the image in an attempt to ingratiate himself with the local aristocracy. “By flaunting his knowledge of the myths of high culture,” he says, “the homeowner could have been trying to elevate his social status.”

House of Orion and House of Jupiter

The House of Orion and the House of Jupiter lie side by side. Ruben Montoya wrote: First excavated in the 18th century, this domus on the Via di Nola, was named for a small painting of the Roman god found in the home’s lararium. The most recent Pompeii excavations have returned to this domus to obtain a fuller picture of its architecture, decor, and history.[Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

There are stucco panels painted to look like marble, a common “faux finish” in the second century B.C. Other myth-inspired frescoes, along with figures of maenads and satyrs, adorn the walls, creating a kind of Dionysian celebration. “These are iconographies that this specific social and political class liked,” said Massimo Osanna, the site’s director. The use of so much of this iconography, however, suggests to Osanna that this person was newly rich, perhaps a freed slave, who was trying hard to appear culturally sophisticated.[Source Ruben Montoya, National Geographic History, July 24, 2020]

In 2018 archaeologists uncovered a stunning and highly unusual mosaic of an enigmatic mythological episode. Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The mosaic showed a winged half-man, half-scorpion with hair ablaze, suspended over a coiled snake. “As far as we knew, the figure was unknown to classical iconography,” says Osanna. Eventually he identified the character as the hunter Orion, son of the sea god Neptune, during his transformation into a constellation. “There is a version of the myth in which Orion announces he will kill every animal on Earth,” Osanna explains. “The angered goddess Gaia sends a scorpion to kill him, but Jupiter, god of sky and thunder, gives Orion wings and, like a butterfly leaving the chrysalis, he rises above Earth — represented by the snake — into the firmament, metamorphosing into a constellation.”[Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, September 2019]

Following more studies, the researchers came to the conclusion that the mosaic formed part of a separate house, lying adjacent to the House of Jupiter, now called the House of Orion. The mosaic and other finds in this home have provided new insight into the upper echelon of Pompeian society. The owner of this house was not only wealthy but cultured. The atrium, for example, features old-fashioned First style, while the bedrooms are decorated in the contemporary Third or Fourth style. Archaeologists contend that the owner’s choices intended to show off his appreciation for both the classic and the new.

House of the Garden

House of the Garden in Regio V is a relatively newly excavated residence that is so named because it once featured a lovely, verdant courtyard surrounded by a low wall decorated with images of plants. Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Roman religious practices were evident at the villa. The shrine to the household gods — or lararium — is embedded in a chamber with a raised pool and sumptuous ornamentation. Beneath the shrine was a painting of two large snakes slithering toward an altar that held offerings of eggs and a pine cone. The blood-red walls of the garden were festooned with drawings of fanciful creatures — a wolf, a bear, an eagle, a gazelle, a crocodile. “Never before have we found such complex decoration within a space dedicated to worship inside a house,” marvels Osanna. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, September 2019]

Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker: The rooms of the mansion were sumptuous, especially one in which a round fresco of a woman’s face — handsome, with deep-set eyes and a long, straight nose — looked out from a wall. Perhaps it was a portrait of the lady of the house. During the excavation of the mansion, a horrifying scene had been found: the skeletons of men, women, and children who had sought refuge in an inner room of the house, trying to shield themselves from the ash, the heat, and the gases spewed by the volcano. In the same building, archeologists discovered a box filled with amulets: figurines, phalluses, and engraved beads. In announcing the find, Massimo Osanna, ever the showman, had called it a “sorcerers’ treasure trove,” noting that the items contained no gold and therefore might have belonged to a servant or an enslaved person. Such items were commonly associated with women, Osanna had noted, and might have been worn as charms against bad luck. [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, November 22, 2021]

“Other scholars have warned that the suggestion of a sorcerer, or sorceress, verges on embellishment, given the paucity of material evidence. The contents of the box are now displayed in the Pompeii museum, with no mention of a sorcerer in the accompanying text. Yet, as the daylight dwindled in Pompeii, it was tempting to follow Osanna’s lead and imagine the scene: terrified members of the household clutching one another, their social differences levelled by disaster, as a Pompeiian who believed in dark magic made unavailing imprecations against unrelenting gods. My mystical vision evaporated, however, after the mansion’s custodian showed me another inscription, which had been scratched into the lintel of the house’s external doorway. It read “Leporis fellas”: “Leporis sucks dick.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024