Home | Category: Food and Sex

PROSTITUTES IN ANCIENT ROME

The skeleton of a woman with buck teeth at Herculaneum was judged to be a prostitute by the structure of her pelvic bones. At the top end of the sex trade were elegant courtesans A man captivated with a courtesan named Novelli Primigenia, who lived and worked in the “Venus Quarter” of Nuceria near Naples, wrote:”Greetings to you, Primgenia of Nuceria. Would that I were the gemstone (of the signet ring I gave you), if only for one single hour, so that, when you moisten it with your lips to seal a letter. I can give you all the kisses that I have pressed on it."

The skeleton of a woman with buck teeth at Herculaneum was judged to be a prostitute by the structure of her pelvic bones. At the top end of the sex trade were elegant courtesans A man captivated with a courtesan named Novelli Primigenia, who lived and worked in the “Venus Quarter” of Nuceria near Naples, wrote:”Greetings to you, Primgenia of Nuceria. Would that I were the gemstone (of the signet ring I gave you), if only for one single hour, so that, when you moisten it with your lips to seal a letter. I can give you all the kisses that I have pressed on it."

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “Graeco-Roman domestic sexuality rested on a triad: the wife, the concubine and the courtesan. The fourth century B.C. Athenian orator Apollodoros made it very clear in his speech Against Neaira quoted by Demosthenes that 'we have courtesans for pleasure, and concubines for the daily service of our bodies, but wives for the production of legitimate offspring and to have reliable guardians of our household property'. Whatever the reality of this domestic set-up in daily life in ancient Greece, this peculiar type of 'ménage à trois' pursued its course unhindered into the Roman period: monogamy de jure appears to have been very much a façade for polygamy de facto. [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

“Since the Roman Republic, according to Tacitus (Ann. II.85.1-2), male and female prostitutes had been recorded nominally in registers which were kept under the guardianship of the aediles. From the reign of Caligula, prostitutes were taxed (Suet. Cal. 40)....There were two categories of Byzantine harlots: on the one hand, actresses and courtesans (scenicae), on the other, poor prostitutes (pornai) who fled from rural poverty and flocked to the great urban centres such as Constantinople and Jerusalem. There, even greater destitution pushed them straight into the rapacious hooks of crooks and pimps. ~

“The advent of Christianity upset this delicate equilibrium. By forbidding married men to have concubines on pain of corporal punishment, canon law elaborated at Church councils took away from this triangular system one of its three components. Henceforth, there remained only the wife and the courtesan.... Besides the sin of lust punished by illness with which prostitutes contaminated all those who approached them physically, harlots embodied also the sin of sexual pleasure amalgamated with that of non-procreative sex condemned by the Church Fathers. The Apostolic Constitutions (dated from A.D. 375 to 380) forbade all non-procreative genital acts, including anal sex and oral intercourse. The art displayed by prostitutes consisted precisely in making full use of sexual techniques which increased their clients' pleasure. Not surprisingly therefore, Lactantius (A.D. 240-320) condemned together sodomy, oral intercourse and prostitution.” ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEX IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF SEX IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PRIAPUS AND PHALLUSES IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ORAL SEX AND SEX POSITIONS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com ;

MASTURBATION, SODOMY, MIRRORS AND BESTIALITY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ADULTERY IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OVER-SEXED EMPERORS AND THEIR FAMILY MEMBERS europe.factsanddetails.com

GAY MEN AND LESBIANS IN ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

SEX POETRY FROM ANCIENT ROME factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome” by Thomas A. J. McGinn (2003) Amazon.com;

“Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World” by Anise K. Strong (2016) Amazon.com;

“Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World” by Christopher A. Faraone and Laura K. McClure (2006) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook (Bloomsbury) by Bonnie MacLachlan (2013) Amazon.com;

“A Rome of One's Own: The Forgotten Women of the Roman Empire” by Emma Southon (2024) Amazon.com;

“Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250" by John Clarke and Michael Larvey (2003) Amazon.com;

“Sex and Sexuality in Ancient Rome” by L J Trafford (2021) Amazon.com;

“Controlling Desires: Sexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Kirk Ormand (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sex on Show: Seeing the Erotic in Greece and Rome” by Caroline Vout (2013) Amazon.com;

“Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture” by Marilyn B. Skinner Amazon.com;

“Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook” (Routledge)

by Marguerite Johnson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Sex Lives of the Roman Emperors by Nigel Cawthorne (2006) Amazon.com;

“Caesars' Wives: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Roman Empire”, Illustrated, by Annelise Freisenbruch (2011) Amazon.com;

“Sex in Antiquity: Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the Ancient World” by Mark Masterson, Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz, et al. (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Sleep of Reason: Erotic Experience and Sexual Ethics in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Martha C. Nussbaum , Juha Sihvola (2002) Amazon.com;

The Erotic Poems (Penguin Classics) by Ovid and Peter Green (1983) Amazon.com;

“From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins: Sex and Category in Roman Religion”

by Ariadne Staples | Feb 1, 2013 Amazon.com;

“Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity” by Sarah Pomeroy (1995) Amazon.com;

“Women's Life in Greece and Rome: A Source Book in Translation” by Maureen B. Fant and Mary R. Lefkowitz (2016) Amazon.com;

“Love in Ancient Rome” by Pierre Grimal (1986) Amazon.com;

“In the Orbit of Love: Affection in Ancient Greece and Rome” by David Konstan (2018) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Sex and Death: The Family and the Fall of the Roman West” by Emma Southon (2017) Amazon.com;

“Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian”

by Susan Treggiari (1991) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome” by Beryl Rawson (1996) Amazon.com;

“Revisiting Rape in Antiquity: Sexualised Violence in Greek and Roman Worlds”

by Susan Deacy, José Malheiro Magalhães, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

Ancient Roman Brothels

baths sometimes served as brothels

Many towns had brothel-taverns. Cities often had brothel districts. But historians said that there were less of them than has been made out to be . The average tourist visit, according to Cambridge classic professor Mary Beard, was three minutes.

Many public baths were thought to double as brothels: One found at present-day Ashkelon in Israel contained a plastered tub that read “Enter, enjoy and ..." Many brothels were small and cramped. Many wealthy families rented out rooms that were used as brothels. The rent is thought to have helped maintain the luxurious lifestyle of their owners. These often had signs with short inscriptions that described what services were offered.

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “Prostitution was also institutionalised under the form of brothels which Juvenal called lupanaria (Sat. 11.172-173) and Horace fornices (Ep. 1.14.21). These, John Moschus described in his sixth-century Spiritual Meadow as a 'house of prostitution' in Jericho or even more vaguely 'an abode of lust' in Jerusalem (Prat. Spir. 17). The prostitutes who were employed in these establishments were slaves and the property of a pimp (leno) or of a 'Madam' (lena). The very name of the prostitute in Tyre who called out to a monk to save her - Kyria Porphyria - is telling. She was so used as a 'Madam' to boss other women, that once she had been reformed and had convinced other harlots (presumably her former 'girls') to give up prostitution, she organised them into a community of nuns of which she became the abbess - the mirror image of her brothel.” [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3]

Roman Laws Regarding Prostitutes

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Roman law developed as a mixture of laws, senatorial consults, imperial decrees, case law, and opinions issued by jurists. One of the most long lasting of actions” of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian' (A.D. 482-566) “was the gathering of these materials in the 530s into a single collection, later known as the Corpus Iuris Civilis [The Code of Civil Law]. The texts here address the issue of marriage, and date back particularly to the time of Augustus [ruled 27 B.C. - A.D. 14] who was very concerned about family matters and ensuring a large population. In the selections that follow the first part comes from the Digest and contain the opinions on marriage law of famous lawyers - Marcianus, Paulus, Terentius Clemens, Celsus, Modestinus, Gaius, Papinianus, Marcellus, Ulpianus, and Macer. Note that the most important were Papinianus (executed by the Emperor Caracalla in 212), who excelled at setting forth legal problems arising from cases, and Ulpianus (d. 223), who wrote a commentary on Roman law in his era.” [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329] [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329]

Taverns like this one in Ostia Antica could also serve as brothels

Marcellus, Digest, Book XXVI: It is understood that disgrace attaches to those women who live unchastely, and earn money by prostitution, even if they do not do so openly. (1) If a woman should live in concubinage [this was legal state of sexual domestic partnership without official "marriage" (connubium) or dowry] with someone besides her patron, I say that she does not possess the virtue of the mother of a family

Ulpianus, On the Lex Julia et Papia, Book I: We hold that a woman openly practices prostitution, not only where she does so in a house of ill-fame, but also if she is accustomed to do this in taverns, or in other places where she manifests no regard for her modesty. 1) We understand the word "openly" to mean indiscriminately, that is to say, without choice, and not if she commits adultery or fornication, but where she sustains the role of a prostitute. 2) Moreover, where a woman, having accepted money, has intercourse with only one or two persons, she is not considered to have openly prostituted herself. 3) Octavenus [a minor Roman jurist], however, says very properly that where a woman publicly prostitutes herself without doing so for money, she should be classed as a harlot. [Lex Julia is an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the Julian family. Most often it refers to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 B.C., or to a law from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar]

4) The law brands with infamy [not just a bad reputation but a legal state which removed certain legal protections] not only a woman who practices prostitution, but also one who has formerly done so, even though she has ceased to act in this manner; for the disgrace is not removed even if the practice is subsequently discontinued. 5) A woman is not to be excused who leads a vicious life under the pretext of poverty. 6) The occupation of a pander is not less disgraceful than the practice of prostitution. 7) We designate those women as procuresses who prostitute other women for money.... 9) Where one woman conducts a tavern, and keeps others in it who prostitute themselves, as many are accustomed to do under the pretext of a employing women for the service of the house; it must be said that they are included in the class of procuresses.”

Where Roman and Byzantine Prostitutes Worked

In the Streets: Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “Byzantine erotic epigrams, notably those of Agathias Scholasticus in the sixth century, generally describe encounters with prostitutes in the street. The winding, dark alleyways of the Old City of Jerusalem were particularly appropriate for soliciting by scortae erraticae or ambulatrices. These lurked under the high arches which bridged the streets of the Holy City and walked up and down the cardo maximus. In the small towns of Roman and Byzantine Palestine, however, it seems that the squares (not the streets) were the favourite hunting-grounds of prostitutes. Rabbi Judah observed: "'How fine are the works of this people [the Romans] ! They have made streets, they have built bridges, they have erected baths !'. Rabbi Yose was silent. Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai answered and said, 'All what they made, they made for themselves; they built market-places, to set harlots in them; baths to rejuvenate themselves; bridges to levy tolls for them'" (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 33b). [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

fresco from a Pompeii ristorante At Home: “Some harlots worked at home, either on their own account, such as Mary the Egyptian whose Life was written down in the sixth century by Sophronios, the last Patriarch of Jerusalem before the Arab Conquest, or for a pimp. On the evidence of the legislation of Emperor Justinian in the mid-sixth century, in particular Novella 14 of 535, it is clear that providing housing was part of the deal which the pimps of Constantinople struck with the fathers of the young peasant girls whom they bought in the capital's hinterland. Housing did not necessarily mean a house, and was frequently only a shack, hut or room. Byzantine prostitutes were relegated to 'red light districts' in the same way that the prostitutes of Rome lived and worked predominantly in Subura and near the Circus Maximus, thus to the north and south of the Forum. In the late sixth-century Life of John the Almsgiver, Patriarch of Alexandria, Leontios of Neapolis describes a monk coming to Tyre on some errand. As he passed through 'the place', he was accosted by a prostitute who cried out: 'Save me, Father, like Christ saved the harlot', this referring to Luke 7:37. These districts were generally the most destitute areas in town. The Babylonian Talmud relates how Rabbi Hanina and Rabbi Hoshaia, both poor cobblers in the Land of Israel, dwelt in a street of harlots for whom they made shoes. The prostitutes were so impressed by these rabbis' chastity (for they would not even lift their eyes to look at the girls) that they took to swearing 'by the life of the holy rabbis of Eretz Yisrael'! ~

In Tavernae: “In city inns (tavernae) as well as in the staging posts for change of mounts (mutationes) or overnight stay (mansiones) along the official Roman road network (the cursus publicus), all the needs of travellers were catered for by the barmaids. They served them wine, danced for them and often led them upstairs to the rooms on the upper floor. In fact, according to the Codex Justinianus, a barmaid could not be prosecuted for adultery, since it was presumed that she was anyway a prostitute. In order to prevent Christian travellers from falling prey to sexual dangers of this sort, ecclesiastical canons forbade the clergy to enter those establishments. Soon, therefore, ecclesiastical resthouses (xenodochia) and inns specifically for pilgrims (pandocheia) run by members of the clergy, sprang up along the main pilgrim routes. ~

Actress-Courtesans and Byzantine Empress Theodora

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “The scenicae were involved in a craft aimed primarily at theatre-goers. It has been described as a 'closed craft', since daughters took over from their mothers. The classic example is that of the mother of the future Empress Theodora who put her three young daughters to work on the stage of licentious plays. The poet Horace described in his Satires (1.2.1) Syrian girls (whose name ambubaiae probably derived from the Syrian word for flute, abbut or ambut) livening up banquets by dancing lasciviously with castanets and accompanied by the sound of flutes. Suetonius simply equated these with prostitutes (Ner. 27). That is why Jacob, Bishop of Serûgh (451-521) in Mesopotamia warned in his Third Homily on the Spectacles of the Theatre against dancing, 'mother of all lasciviousness' which 'incites by licentious gestures to commit odious acts'. A sixth-century mosaic in Madaba in Transjordan depicts a castanet-snapping dancer dressed in transparent muslin next to a satyr who is clearly sexually-roused. [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

Theodora

“According to Bishop John of Ephesus' fifth-century Lives of the Eastern Saints, Emperor Justinian's consort was known to Syrian monks as 'Theodora who came from the brothel'. Her career proves that Byzantine courtesans like the Ancient Greek hetairai could aspire to influential roles in high political spheres. Long before her puberty, Theodora worked in a Constantinopolitan brothel where, according to the court-historian Procopius of Caesarea's Secret History, she was hired at a cheap rate by slaves as all she could do then was to act the part of a 'male prostitute'. As soon as she became sexually mature, she went on stage, but as she could play neither flute nor harp, nor even dance, she became a common courtesan. ~

“Once she had been promoted to the rank of actress, she stripped in front of the audience and lay down on the stage. Slaves emptied buckets of grain into her private parts which geese would peck at. She frequented banquets assiduously, offering herself to all and sundry, including servants. She followed to Libya a lover who had been appointed Governor of Pentapolis. Soon, however, he threw her out, and she applied her talents in Alexandria and subsequently all over the East. Upon her return to Constantinople, she bewitched Justinian who was then still only the heir to the imperial throne. He elevated his mistress to Patrician rank. Upon the death of the Empress, his aunt and the wife of Justin II (who would never have allowed a courtesan at court), Justinian forced his uncle Justin II to abrogate the law which forbade senators to marry courtesans. Soon, he became co-emperor with his uncle and at the latter's death, as sole emperor, immediately associated his wife to the throne (Anecd. 9.1-10).” ~

Poor Prostitutes in Ancient Rome and Byzantium

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “Only a few courtesans could climb the social ladder in this phenomenal way. Most prostitutes who worked in brothels and tavernae and are described as pornai, were slaves or illiterate peasant girls like Mary the Egyptian who later became a holy hermit in the Judaean desert. Because neither hetairai nor pornai had any legal status, and since hetairai were also slaves belonging to a pimp or to a go-between, the distinction between courtesans and pornai was based entirely on their different financial worth. This aspect of the trade was inherent in the Latin name meretrix for prostitute, meaning 'she who makes money from her body'. [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

“Three types of prices should be taken into consideration: the price for buying, the price for redeeming and the price for hiring. The peasants of the Constantinopolitan hinterland sold their daughters to pimps for a few gold coins (solidi). Thereafter, clothes, shoes and a daily food-ration would be these miserable girls' only 'salary'. To redeem a young prostitute in Constantinople under the reign of Justinian was cheap (Novell. 39.2). It cost 5 solidi, thus only a little more than the amount needed to buy a camel (41/3 solidi) and a little less than for a she-ass (51/3 solidi) or a slave-boy (6 solidi) in Southern Palestine at the end of the sixth century or in the early seventh century. That women could be degraded to the extent of being ranked with beasts of burden tells us much about Byzantine society. ~

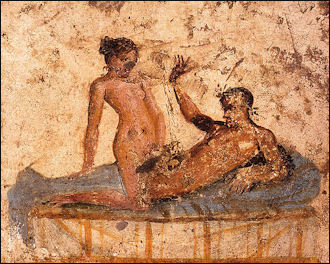

from a Pompeii brothel “In Rome and Pompeii, the services of a 'plebeia Venus' cost generally two asses - no more than a loaf of bread or two cups of wine at the counter of a taverna. Whereas the most vulgar kind of prostitute would only cost 1 as (Martial claimed in Epig. 1.103.10: 'You buy boiled chick peas for 1 as and you also make love for 1 as'), R. Duncan-Jones notes that the Pompeian charge could be as high as 16 asses or 4 sestercii.[8] In early seventh-century Alexandria, the average rate for hiring a prostitute is provided by the Life of John the Almsgiver. As a simple worker, the monk Vitalius earned daily 1 keration (which was worth 72 folleis) of which the smallest part (1 follis) enabled him to eat hot beans. With the remaining 71 folleis, he paid for the services of a prostitute which being a saint, he naturally did not use, for his aim was to convert them to a Christian life. ~

“Lack of clients over several days meant poverty and hunger. Thus a harlot in Emesa, modern Homs in central Syria, had only tasted water for three days running, to which St Symeon Salos remedied by bringing her cooked food, loaves of bread and a pitcher of wine. On days when she earned a lot, Mary the Egyptian prostitute in Alexandria ate fish, drank wine excessively and sang dissolute songs presumably during banquets. In denouncing the Byzantine courtesans' obscene lust for gold, the sixth-century rhetor Agathias Scholasticus echoed the authors of the fourth-century B.C. Athenian Middle Comedy. In particular, the poet Alexis claimed that 'Above all, they [the prostitutes] are concerned with earning money'.[9] Sometimes a prostitute's jewellery was her sole wealth. When in 539, the citizens of Edessa, modern Urfa in south-eastern Turkey, decided to redeem their fellow-citizens who were held prisoners by the Persians, the prostitutes (who did not have enough cash) handed over their jewels (Procop. De Bell. Pers. 2.13.4).” ~

Brothels in Pompeii

There were at least 25 brothels in Pompeii.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Excavations at Pompeii uncovered a number of brothels, the most famous of which — the Lupanare (wolf’s den) — was built specifically for this purpose. This wasn’t the case with all ancient brothels which, as Professor Sarah Bond has written in Trade and Taboo, could set up shop in inns, taverns and even mills. The Lupanare contained ten rooms, each of which was furnished with a stone bed and mattress that were separated from an antechamber by a curtain. [Source:Candida Moss, Daily Beast, 2017]

Ben Gazur wrote in Listverse: In most societies, prostitution has been, if not illegal, then at least looked on as something deeply shameful. For the Romans, this was not the case. The Lupinar in the ruins of Pompeii gives us a peek into the world of the Roman brothel. Instead of hidden away in a dank alley, it proudly asserts the sort of business one could do inside. Graffiti tells people what to expect from the various women on offer. Once inside, several graphic images help those with less imagination or the illiterate understand just what they were buying.[Source Ben Gazur, Listverse, January 7, 2017]

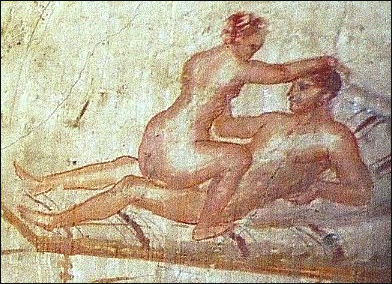

Some places looked like they should have been brothels but weren't. The he House of the Vetti (on V. della Fortuna) is one of the most popular villas at Pompeii. The Ixon Room in the villa looks like a small art gallery. There are delightful murals with cherubs performing tasks like forging, goldsmithing and making weapons. The biggest draw are the erotic frescoes and statues. A fresco beside the entrance to the villa shows the god of fertility Priapus, whose penis is so large it is held up by a string. Off in a side room to the right of the Priapus entrance is statue of Priapus with his penis erect and erotic frescoes of couples having sexual intercourse sitting down and in other positions. In Roman times, rooms with erotic art were generally only for men and their concubines.

Brothels in Palestine

Excavations of an ancient sewer under a Roman bathhouse in Ashkleon in present-day Israel revealed the remains of more than 100 infants thought be unwanted children from the brothel. They infants had been thrown into a gutter along with animal bones, pottery shards and a few coins and are thought to have been unwanted because of the way they were disposed. DNA tests revealed that 74 percent of the victims were male. Usually unwanted children were girls.

so-called brothel at Pompeii

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “A Byzantine brothel has recently been unearthed in the course of excavations at Bet She'an, ancient Scythopolis, capital of Palaestina Prima.[6] At the heart of this thriving metropolis, a Roman odeon founded in the second half of the second century was partly destroyed in the sixth century. Byzantine Baths adjoined it to the west. To the south-west, the second row of shops of the western portico of the impressive Street of Palladius was also dismantled to make way for a semi-circular exedra (13x15m). Each half of the exedra comprised six trapezoidal rooms with front doors. Some of these rooms also opened onto a corridor or a hall at the back of the building. In one room, a staircase led to an upper storey. Some rooms had niches with grooves for wooden shelves. The apses at both ends of the exedra and in the centre of the semi-circle, as well as the façades of the rooms were revetted with marble plaques, most of which are now lost, there only remaining holes for the nails which held these plaques in position. The inner faces of the walls of these rooms exhibited two coats of crude white plaster. [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

“The floor of most of these rooms was paved with mosaics depicting geometric motifs enclosing poems in Greek, animals and plants, and lastly, in an emblema, a magnificent Tyche crowned by the walls of Scythopolis and holding a cornucopia. The mosaic pavements of some rooms had been subsequently replaced by bricks or a layer of crushed lime. Traces of crude repairs in the mosaics and the insertion of benches in other rooms indicated that the building had undergone various stages of construction. A semi-circular courtyard (21x30m) stretched in front of the twelve rooms. Towards the street, it was closed off by a set of rooms which incorporated the shops previously at the northern end of the portico of the Street of Palladius, whilst putting them to a different use. This row of rooms which was probably interrupted by the main entrance into the complex, opened onto a portico with an opus sectile floor of black and white marble. Two steps running for the entire length of the portico enabled access from the street. The portico and the rooms had a tiled roof. The exedra was demolished at the end of the sixth century or in the early seventh century. ~

“The cabins of the Bet She'an exedra are reminiscent of the cells of the Pompeii lupanarium which consisted of ground floor rooms, each equipped with a stone bed and a bolster. An external staircase provided access to the first floor balcony onto which opened five more spacious rooms. At Bet She'an, the back doors of some rooms on the ground floor enabled clients who were keen to remain anonymous, to enter an abode of lust without being seen from the main street and thus to surreptitiously satisfy their sexual fantasies. ~

“The portico where the girls strolled in the hope of attracting passers-by from the Street of Palladius, as well as the neighbouring Byzantine Baths were part of a fascinating network: soliciting at the Baths, in the portico and in the exedra courtyard, followed by sex in the cabins; and at the back of the building, an entrance-and-exit system for supposedly 'respectable clients'.” ~

Prostitution and Baths in Ancient Rome and Byzantium

bath frigidarium

Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “Famous courtesans and common harlots, all met in the public Baths which were already frequented in the Roman period by prostitutes of both sexes. Some of these baths were strictly for prostitutes and respectable ladies were not to be seen near them (Mart. Epigr. 3.93). Men went there not to bathe, but to entertain their mistresses as in sixteenth-century Italian bagnios. The fourth-to-sixth-century Baths uncovered in Ashqelon in 1986 by the Harvard-Chicago Expedition appear to have been of that type. The excavator's hypothesis is supported both by a Greek exhortation to 'Enter and enjoy...' which is identical to an inscription found in a Byzantine bordello in Ephesus, and by a gruesome discovery.[10] [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

“The bones of nearly 100 infants were crammed in a sewer under the bathhouse, with a gutter running along its well-plastered bottom. The sewer had been clogged with refuse sometime in the sixth century. Mixed with domestic rubbish - potsherds, animal bones, murex shells and coins - the infant bones were for the most part intact. Infant bones are fragile and tend to fragment when disturbed or moved for secondary burial. The good condition of the Ashqelon infant bones indicates that the infants had been thrown into the drain soon after death with their soft tissues still intact. The examination of these bones by the Expedition's osteologist, Professor Patricia Smith of the Hadassah Medical School - Hebrew University of Jerusalem, revealed that all the infants were approximately of the same size and had the same degree of dental development. Neonatal lines in the teeth of babies prove the latters' survival for longer than three days after birth. The absence of neonatal lines in the teeth of the Ashqelon babies reinforces the hypothesis of death at birth. ~

“Whilst it is conceivable that the infants found in the drain were stillborn, their number, age and condition strongly suggest that they were killed and thrown into the drain immediately after birth. Thus, the prostitutes of Ashqelon used the Baths not only for hooking clients but also for surreptitiously disposing of unwanted births in the din of the crowded bathing halls. It is plausible that the monks and rabbis were aware of this and that this (and not only the fear of temptation) was their main reason for equating baths with lust. ~

bath tepidarium

“In the eyes of the pious Jews of Byzantine Palestine, any public bathhouse which was not used for ritual purification (mikveh) was tainted with idolatry, not only because it belonged to Gentiles, but also because a statue of Venus stood at the entrance of many bathhouses. The statue of Venus greeting the users of the Baths of Aphrodite at Ptolemais-'Akko which the Jewish Patriarch Gamaliel II regularly frequented, was invoked by Proclus the Philosopher to accuse Gamaliel of idolatry. The Patriarch succeeded in clearing himself of this charge by demonstrating that the statue of Aphrodite simply adorned the Baths and in no sense was an idol (Mishna, Abodah Zarah 3.4). ~

“Nevertheless, Venus which Lucretius (4.1071) had dubbed Volgivaga - 'the street walker' - was the patron of prostitutes who celebrated her feast on 23 April late into the Byzantine period. This, too, must explain the intense hostility of some rabbis towards the public baths of the Gentiles over which the goddess ruled both in marmore and in corpore. Since Biblical times, lust had always been intimately associated with the idolatrous worship of the ashera - a crude representation of the Babylonian goddess of fertility Ishtar who had become the Canaanite, Sidonian and Philistine Astarte and the Syrian Atargatis (1 Kgs 14.15) - as well as with the green tree under which an idol was placed (1 Kgs 14.23; Ez 6.13). Had the prophet Jeremiah (2.20) not accused Jerusalem of prostituting herself: 'Yea, upon every high hill / and under every green tree, / you bowed down as a harlot'?” ~

Sources of Prostitutes in Ancient Rome and Byzantium

It is believed that some prostitutes unwanted girls legally abandoned by their parents at infancy (See Roman Infanticide). Claudine Dauphin of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Paris wrote: “According to Apollodoros' Against Neaira, Greek hetairai predominantly bought young female slaves or adopted new-born girls who had been exposed. They educated them in the prostitutes' trade and confined them to the brothels until these girls were old enough to ply their trade themselves and support their adopted mothers in their old age.” [Source: “Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land” by Claudine Dauphin, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Classics Ireland ,University College Dublin, Ireland, 1996 Volume 3 ~]

On why more boys were killed at the bath-brothel in Askelon, Dauphin wrote: “Consequently, in a society of prostitutes, would Petersen's 'natural' selection not have been reversed? Baby girls would have been kept alive and brought up in brothels so that eventually they would be able to pick up the trade from their mothers when the latters' attraction had faded. It would not have been possible to raise baby boys in the same way.

“Tainted by the sins of lust, of sexual enjoyment and murder, Byzantine prostitutes, were never 'branded', unlike the Roman prostitutes who by law had to look different from respectable young women and matrons and were therefore made to wear the toga which was strictly for men (Hor. Sat. 1.2.63); unlike, too the mediaeval harlots of Western Europe who are consistently depicted wearing striped dresses, stripes being the iconographic attribute of 'outlaws' such as lepers and heretics. Descriptions of the physical aspect of Byzantine prostitutes are at best vague, such as 'dressed like a mistress' in Midrash Genesis Rabbah (23.2). We can only imagine their appearance from fragmentary evidence, such as blue faience beaded fish-net dresses worn by prostitutes in Ancient Egypt.” ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024