Home | Category: Themes, Archaeology and Prehistory

ERUPTION OF VESUVIUS IN A.D. 79

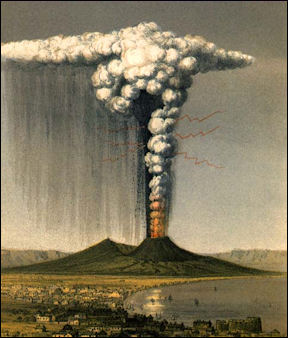

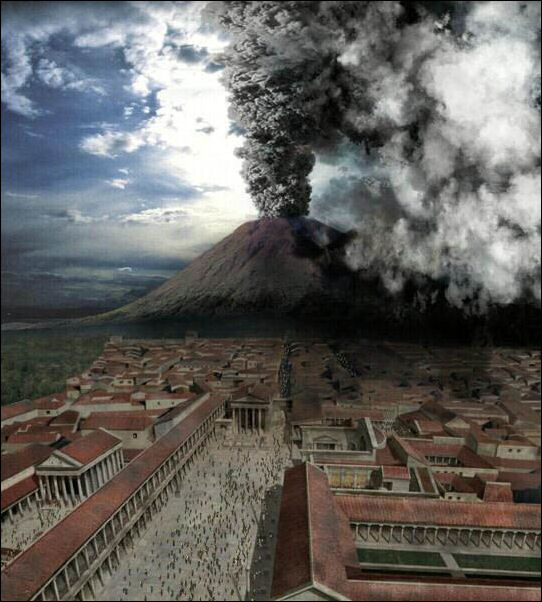

ash deposits from AD 79 eruption At about 1:00pm on August 24 (or late October), A.D. 79 Vesuvius exploded like a powerful nuclear weapon. After about a half an hour volcanic debris started to cover Pompeii. For 11 hours the volcano thrust a column of pumice, ash and fumes 33 kilometers (20½ miles) into the stratosphere at a rate of 1.5 million tons per second, turning day into night and releasing more thermal energy than 100,000 Hiroshima atomic bombs. Warning signs before the eruption included an earthquake a few weeks before and wells mysteriously going dry. There was no lava, the eruption was too violent for that.

As the column of ash and cinders cooled it began to spread horizontally and drift with the wind. As it cooled further solid particles began raining down. Pompeii and the ancient city of Stabiae were buried under the volcanic debris while Heracuelum succumbed to fiery avalanches of gas and volcanic debris. The event is sometimes called the pliny eruption because it was described by great Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, who died in the eruption, and his nephew Pliny the Younger, who was 30 kilometers away in Misenum.

There were 15 earthquakes before Mt. Vesuvius erupted and covered Pompeii. Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “It was on the afternoon of August 24, A.D. 79, that people living around long-dormant Mount Vesuvius watched in awe as flames shot suddenly from the 4,000-foot volcano, followed by a huge black cloud. “It rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches, I imagine because it was thrust upwards by the first blast and then left unsupported as the pressure subsided,” wrote Pliny the Younger. “Sometimes it looked white, sometimes blotched and dirty, according to the amount of soil and ashes it carried with it.”[Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, July 2015 ~|~]

“Volcanologists estimate that the eruptive column was expelled from the cone with such force that it rose as high as 20 miles. Soon a rain of soft pumice, or lapilli, and ash began falling over the countryside. That evening, Pliny observed, “on Mount Vesuvius broad sheets of fire and leaping flames blazed at several points, their bright glare emphasized by the darkness of night.”Many people fled as soon as they saw the eruption. But the lapilli gathered deadly force, the weight collapsing roofs and crushing stragglers as they sought protection beneath staircases and under beds. Others choked to death on thickening ash and noxious clouds of sulfurous gas.In Herculaneum, a coastal resort town about one-third Pompeii’s size, located on the western flank of Vesuvius, those who elected to stay behind met a different fate. Shortly after midnight on August 25, the eruption column collapsed, and a turbulent, superheated flood of hot gases and molten rock—a pyroclastic surge—rolled down the slopes of Vesuvius, instantly killing everyone in its path.~|~

“Pliny the Younger observed the suffocating ash that had engulfed Pompeii as it swept across the bay toward Misenum on the morning of August 25. “The cloud sank down to earth and covered the sea; it had already blotted out Capri and hidden the promontory of Misenum from sight. Then my mother implored, entreated and commanded me to escape as best I could....I refused to save myself without her and grasping her hand forced her to quicken her pace....I looked round; a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood.” Mother and son joined a crowd of wailing, shrieking and shouting refugees who fled from the city. “At last the darkness thinned and dispersed into smoke or cloud; then there was genuine daylight....We returned to Misenum...and spent an anxious night alternating between hope and fear.” Mother and son both survived. But the area around Vesuvius was now a wasteland, and Herculaneum and Pompeii lay entombed beneath a congealing layer of volcanic material.... Doomed by proximity to Vesuvius, the two cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were entombed within a day. Accounts at the time documented the spread of the ash cloud beyond Rome, as far as Egypt and Syria. ~|~

RELATED ARTICLES:

VESUVIUS: HISTORY, GEOLOGY, DANGERS, ERUPTIONS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POMPEII: HISTORY, BUILDINGS, INTERESTING SITES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HOUSES AND VILLAS AT POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com ;

PAINTINGS FROM POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com

POMPEII ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

POMPEII VICTIMS: THEIR LIVES, CASTS, DEATHS AND DNA europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM VICTIMS: THEIR LIVES, DEATHS AND VAPORIZATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, BUILDINGS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM SCROLLS: HISTORY AND EFFORTS TO UNWRAP THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

READING THE HERCULANEUM PAPYRI: VIRTUAL UNWRAPPING, SYNCHROTRONS AND AI europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Vesuvius: A Biography” by Alwyn Scarth (2009) Amazon.com;

“Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei, and Campanian Volcanism” by Benedetto De Vivo, Harvey E. Belkin, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Neapolitan Volcanoes: A Trip Around Vesuvius, Campi Flegrei and Ischia” (GeoGuide)

by Stefano Carlino (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Eruption of Vesuvius in 1872: Unveiling the Catastrophic Fury of Mount Vesuvius”

by Luigi Palmieri and Robert Mallet (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pliny and the Eruption of Vesuvius” by Pedar W. Foss Amazon.com;

“The Letters of the Younger Pliny (Penguin Classics) by Pliny the Younger and Betty Radice (1963) Amazon.com;

“Ghosts of Vesuvius: A New Look at the Last Days of Pompeii, How Towers Fall, and Other Strange Connections” by Charles R Pellegrino (2005) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: The History, Life and Art of the Buried City” by Marisa Ranieri Panetta (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pompeii”, Illustrated, by Joanne Berry (2007) Amazon.com;

“Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Paul Roberts Amazon.com;

"Pompeii's Living Statues: Ancient Roman Lives Stolen from Death” by Eugene Dwyer | (2010) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Fires of Vesuvius: Pompeii Lost and Found” by Mary Beard (2010) Amazon.com;

“Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum” by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (1996) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii: An Archaeological Guide by Paul Wilkinson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii” by Robert Harris (2003), Novel Amazon.com

“Inside Pompeii”, a photographic tour, by Luigi Spina (2023) Amazon.com;

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

“Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Alison E. Cooley (2013) Amazon.com;

“Herculaneum: Italy's Buried Treasure” by Joseph Deiss (1989) Amazon.com;

“The Library of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by David Sider (2005) Amazon.com;

“Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum” by Kenneth Lapatin (2019) Amazon.com;

Effect of the Eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79 on Pompeii

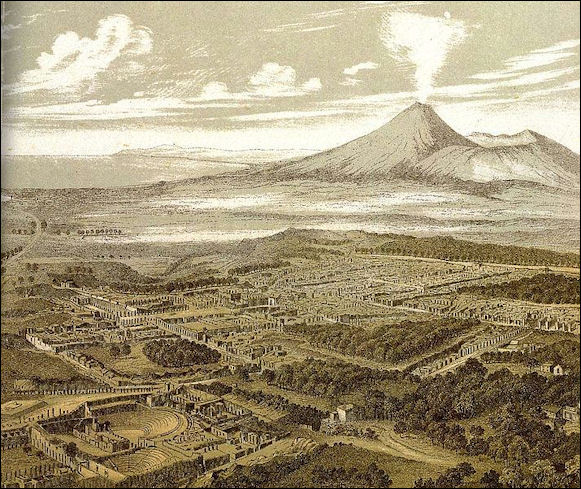

Vesuvius in 1822 Pompeii's fate of being downwind from Vesuvius on that day had more to do than anything else with it being buried by ash. Ash and pumice fell on Pompeii at a rate of six inches an hour. This in itself wasn't enough to kill anyone at first, but mixed in were bowling-ball-size volcanic bombs that were. After four hours roofs began to collapse from the weight of the ash and after 17 hours over 9 feet of ash had fallen.

An estimated 80 percent of Pompeii's resident probably survived by fleeing early. Those that stayed were probably able to survive the ashfall of the first day, if their roofs didn't collapse, by staying indoors and breathing through rags. But on second day, just as the ash was starting to let up and people began venturing outdoors, pyroclastic flows of superheated gas and ash surged through the city. These flows reached Pompeii on August 25. The first at 5:30am stopped just outside Pompeii's walls. The second one, an hour later, entered the city and probably asphyxiated most of its residents. The third and most devastating surge is the one that caused Pliny to flee Misenum. This one, which came three hours after the first, buried Pompeii and entombed its victims.

After that there were more pyroclastic surges as well as mud flows, but by that time everyone that was going to die was already dead, Hall wrote: “The pattern of its deposits, the swirl of its volcanic signature in layers thick and thin, has allowed volcanologists to conclude that Vesuvius unleashed at least six cycles of pyroclastic surge and flow in that single eruption’six bursts of searing winds followed by six rampaging rivers of mud — that destroyed everything within about nine miles of the volcano. The immediate cataclysm probably lasted less than 24 hours, but it turned an idyllic landscape into a monochromatic desert, uninhabitable for 300 years,”

Pompeii Earthquake of A.D. 62

According to Archaeology magazine: The emperor Nero is thought to have visited the southern Italian city of Pompeii in A.D. 64, perhaps spending a few nights in the enormous villa his wife, Poppaea, owned in the nearby town of Oplontis. Nero would have seen a city struggling to recover from a devastating earthquake two years earlier. “Pompeii was a city in crisis and flux,” says archaeologist Stephen Kay of the British School at Rome. The Pompeians labored to fix damaged roads, repaint walls whose frescoes had been ruined, rebuild their homes, revitalize the city’s infrastructure, repair its cemeteries, and construct what they were confident would be a new, earthquake-proof temple to their patron goddess, Venus. The Pompeians may not have known it, but the A.D. 62 earthquake had been a warning that the volcano looming over their city was waking up after 700 years of dormancy. [Source: Benjamin Leonard and Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2019]

The A.D. 62 earthquake was of a magnitude of between 5 and 6 and a maximum intensity of IX or X on the Mercalli scale. It severely damaged Pompeii and Herculaneum. Damage to some buildings was also reported from Naples and Nuceria The contemporary philosopher and dramatist Seneca the Younger wrote an account of the earthquake in the sixth book of his Naturales quaestiones, entitled De Terrae Motu (Concerning Earthquakes). He reported the death of a flock of 600 sheep that he attributed to the effects of poisonous gases. [Source Wikipedia]

The epicentre of the earthquake was close to the southern flank of Vesuvius. There is some uncertainty regarding the year of this earthquake. Seneca, who was writing soon after the event, describes the earthquake as occurring during the consulship of Gaius Memmius Regulus and Lucius Verginius Rufus, which would suggest the year was A.D. 63. In contrast Tacitus, who was writing some forty years later, describes it as occurring during the consulship of Publius Marius and Lucius Afinius Gallus, which indicates A.D. 62. The House of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus in Pompeii, later destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79, contained bas-reliefs showing damage to the city and its Temple of Jupiter during the earthquake of 62. The house's owner, Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, may have died during the earthquake.

New Date for the Vesuvius Eruption?

A charcoal inscription, uncovered in the late 2010s, caused scholars to reset the eruption date of Vesuvius from August to October, Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “One of the central mysteries of that fateful day, long accepted as August 24, has been the incongruity of certain finds, including corpses in cool-weather clothing. Over the centuries, some scholars have bent over backward to rationalize such anomalies, while others have voiced suspicions that the date must be incorrect.” Now there is a clear alternative. [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, September 2019]

“Scratched lightly, but legibly, on an unfinished wall of a house that was being refurbished when the volcano blew is a banal notation in charcoal: “in [d]ulsit pro masumis esurit[ions],” which roughly translates as “he binged on food.” While not listing a year, the graffito, likely scrawled by a builder, cites “XVI K Nov” — the 16th day before the first of November on the ancient calendar, or October 17 on the modern one. That’s nearly two months after August 24, the fatal eruption’s official date, which originated with a letter by Pliny the Younger, an eyewitness to the catastrophe, to the Roman historian Tacitus 25 years later and transcribed over the centuries by monks.

Massimo Osanna, Pompeii’s general director, is convinced that the notation was idly doodled a week before the blast. “This spectacular find finally allows us to date, with confidence, the disaster,” he says. “It reinforces other clues pointing to an autumn eruption: unripe pomegranates, heavy clothing found on bodies, wood-burning braziers in homes, shops selling chestnuts, wine from the harvest in sealed jars. When you reconstruct the daily life of this vanished community, two months of difference are important. We now have the lost piece of a jigsaw puzzle.”

Pliny the Elder and the Eruption of Vesuvius

While most people headed as quickly as they could away from Pompeii, the very curious Roman historian and naturalist Pliny the Elder headed straight for it. At the time of the eruption Pliny and his sister and his teenage nephew, Pliny the Younger, were in a villa overlooking the Roman port of Misenum across the Bay of Naples, 24 kilometers (15 miles) from Vesuvius and 32 kilometers (20 miles) away from Pompeii. Around midday, Elder Pliny’s sister told him something unusual was occurring : a strange cloud had appeared on the horizon. Pliny, who at the time commanded the imperial navy, half of which was based at Misenum, decided to take a closer look.

The elder Pliny considered the eruption a novelty and, taking a Roman fleet with him, sailed towards Pompeii on a scientific-expedition-come-rescue-mission. When he arrived in Stabiae, a coastal town 30 kilometers down the coast close to Vesuvius, he found the town in a state of panic. In the ensuing disaster, like almost everyone else, Pliny the Younger initially stayed behind and wrote an account of what happened, apparently pieced together from his own observations and the accounts of survivors. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, February 9, 2020]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Ironically, as classicist Daisy Dunn has written in her new book, The Shadow of Vesuvius, Pliny was something of an expert on volcanoes. For his Natural History he had written about Mount Etna, Mount Chimera in Lycia (Southern Turkey), as well as volcanoes in Persia, Ethiopia, and the Aeolian islands. He did not, however, write about Vesuvius here, which he elsewhere describes as a vineyard-covered mountain in a very pleasant green region. He had failed to pay attention to the geographer Strabo’s note that the rocks at the summit of Vesuvius looked as if they had been eaten out by fire. Perhaps it was this oversight and his famous curiosity that led him to the beaches of Stabiae and his death.

Pliny the Younger on the Pliny the Elder's Death

Pliny the Younger wrote that Pliny the Elder "had been out in the sun, and taken a cold bath" and "my mother drew his attention to a cloud of unusual size and appearance...It was not clear from which mountain the cloud was rising. Later we knew it was Vesuvius...My uncle's scholarly acumen saw at once it was important enough for a closer inspection and he ordered a boat to be made ready."

"He was entirely fearless...he hurried to the place everyone else was hastily leaving...Ashes were already falling, hotter and thicker as the ships drew near." His boat was bombarded with fiery ashfall and blocked with floating rafts of pumice but eventually he made it to Stabiae which was about the same distance from Pompeii as Pompeii was from Vesuvius.

To calm his friends Pliny told them "the broad sheets of fire and leaping flames" were "nothing but the bonfires left by peasants." Later, while his companions debated whether to stay in their house or flee, Pliny slept soundly through the first night of the eruption. When the houses starting shaking violently, they put pillows on their heads to protect themselves from falling rocks.”

To calm his friends Pliny told them "the broad sheets of fire and leaping flames" were "nothing but the bonfires left by peasants." Later, while his companions debated whether to stay in their house or flee, Pliny slept soundly through the first night of the eruption. When the houses starting shaking violently, they put pillows on their heads to protect themselves from falling rocks.”

Pliny the Elder died in the eruption of Vesuvius. He advised calm when the volcano began erupting and stayed in Pompeii even though he had enough warning to escape. He went outside the day after the initial eruption, on August 25, with a pillow tied to his head. Some think that Pliny the Elder died choked by ash after landing in the beach near Pompeii.

Pliny the Younger wrote that August 25, was "blacker and denser than any ordinary night." Violent waves made escape by sea impossible. Pliny grew tired and repeatedly asked for cold water. Then suddenly the "flames and smell of sulphur" drove his companions to flight. The elder Pliny collapsed, perhaps from a heart attack or from breathing in toxic fumes, and two days later his body was found on a beach at Stabiae "entire an uninjured...its postured that of sleeping, rather than a dead man."

Pliny the Younger and the Eruption of Vesuvius

Meanwhile, Pliny the Younger, who was a safe enough distance away in Minsenum, was interrupted from his studies by a "fearful black cloud” that “was rent by forked and quivering bursts of flame." The cloud moved across the bay "and parted to reveal great tongues of fire like flashes of lightning magnified in size...We also saw the sea sucked away and apparently forced back by the earthquake.” He described the initial cloud as being of “unusual size and appearance.” He said it reminded him of an umbrella pine tree “for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches.”

Pliny the Younger fled along with most of the other terrified residents of Misenum. As the cloud descended," many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into darkness for evermore."

"You could hear the shrieks of women and wailing of infants, and the shouting of men: some were calling for their parents, others their children and wives...There were people, too, who added to the real perils by inventing factious dangers: some reported that a part of Misenum had collapsed or another part was on fire."

"The flames remained a distance off; then darkness came on once more and the ashes began to fall again, this time in heavy showers. We rose from time to time and shook them off, otherwise we should have been buried and crushed beneath the weight.” When the cloud eventually lifted “everything changed, buried deep in ashes like snowdrifts."

Pliny the Younger’s Letter 6.16 on the Vesuvius Eruption

Pliny the Younger (A.D. 61- 113) recorded the events he witnessed from Misenum on the northern arm of the Bay of Naples, about 30 kilometers (19 miles) west of Vesuvius. He wrote to to Cornelius Tacitus in Letter 6.16:“Thank you for asking me to send you a description of my uncle's death so that you can leave an accurate account of it for posterity 1....“My uncle was stationed at Misenum, in active command of the fleet. 2 On 24 August, in the early afternoon, my mother drew his attention to a cloud of unusual size and appearance. He had been out in the sun, had taken a cold bath, and lunched while lying down, and was then working at his books. He called for his shoes and climbed up to a place which would give him the best view of the phenomenon. It was not clear at that distance from which mountain the cloud was rising (it was afterwards known to be Vesuvius); its general appearance can be best expressed as being like an umbrella pine 3, for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches, I imagine because it was thrust upwards by the first blast and then left unsupported as the pressure subsided, or else it was borne down by its own weight so that it spread out and gradually dispersed.

Vesuvius and Pompeii

Sometimes it looked white, sometimes blotched and dirty, according to the amount of soil and ashes it carried with it. My uncle's scholarly acumen 4 saw at once that it was important enough for a closer inspection, and he ordered a boat to be made ready, telling me I could come with him if I wished. I replied that I preferred to go on with my studies, and as it happened he had himself given me some writing to do. [1. Tacitus' description of the eruption of Vesuvius and the death of Pliny the Elder would have been in the part of his Histories that does not survive; remember his narrative breaks off in 70 CE, some years before the volcanic disaster. 2. Pliny the Elder was praefectus classi, praefect of the fleet, appointed by the emperor and holding imperium. 3. A particular kind of pine tree known in the Mediterranean, shaped in outline like an umbrella (hence the name); we would call this a "mushroom cloud". 4. As the author of the encyclopedic Natural History, Pliny would naturally have been interested in this unusual phenomenon] [Source: Pliny the Younger (A.D. 61- 113). Letters 6.16 and 6.20, From Penguin translation by Betty Radice]

“As he was leaving the house, he was handed a message from Rectina, wife of Tascius whose house was at the foot of the mountain, so that escape was impossible except by boat. She was terrified by the danger threatening her and implored him to rescue her from her fate. He changed his plans, and what he had begun in a spirit of inquiry he completed as a hero. He gave orders for the warships 5 to be launched and went on board himself with the intention of bringing help to many more people besides Rectina, for this lovely stretch of coast was thickly populated. He hurried to the place which everyone else was hastily leaving, steering his course straight for the danger zone. He was entirely fearless, describing each new movement and phase of the portent to be noted down exactly as he observed them. Ashes were already falling, hotter and thicker as the ships drew near, followed by bits of pumice and blackened stones, charred and cracked by the flames: then suddenly they were in shallow water, and the shore was blocked by the debris from the mountain. For a moment my uncle wondered whether to turn back, but when the helmsman advised this he refused, telling him that Fortune stood by the courageous 6 and they must make for Pomponianus at Stabiae. He was cut off there by the breadth of the bay (for the shore gradually curves round a basin filled by the sea) so that he was not as yet in danger, though it was clear that this would come nearer as it spread. Pomponianus had therefore already put his belongings on board ship, intending to escape if the contrary wind fell.

This wind was of course full in my uncle's favour, and he was able to bring his ship in. 7 He embraced his terrified friend, cheered and encouraged him, and thinking he could calm his fears by showing his own composure, gave orders that he was to be carried to the bathroom. After his bath he lay down and dined 8; he was quite cheerful, or at any rate he pretended he was, which was no less courageous. [5. Pliny originally was going to head toward Vesuvius in a small light galley; after receiving the note, he ordered out the larger quadriremes, as they were much larger and better able to take numbers of people to safety. 6. Variations on this idiomatic saying, "Fortune favors the brave," can be found in a number of Roman authors. 7. So at first, apparently, wind is blowing toward the mountain, allowing Pliny's sails to push the boats toward the shore, but making it difficult to launch sailboats in flight from Pompeii and/or Herculaneum. The wind would later shift, according to the debris pattern preserved archaeologically. 8. Romans reclined on couches to dine formally.]

“Meanwhile on Mount Vesuvius broad sheets of fire and leaping flames blazed at several points, their bright glare emphasized by the darkness of night. My uncle tried to allay the fears of his companions by repeatedly declaring that these were nothing but bonfires left by the peasants in their terror, or else empty houses on fire in the districts they had abandoned. Then he went to rest and certainly slept, for as he was a stout man his breathing was rather loud and heavy and could be heard by people coming and going outside his door. By this time the courtyard giving access to his room was full of ashes mixed with pumice-stones, so that its level had risen, and if he had stayed in the room any longer he would never have got out. He was wakened, came out and joined Pomponianus and the rest of the household who had sat up all night. They debated whether to stay indoors or take their chance in the open, for the buildings were now shaking with violent shocks, and seemed to be swaying to and fro, as if they were torn from their foundations. Outside on the other hand, there was the danger of falling pumice-stones, even though these were light and porous; however, after comparing the risks they chose the latter. In my uncle's case one reason outweighed the other, but for the others it was a choice of fears. As a protection against falling objects they put pillows on their heads tied down with cloths.

from the Discovery Channel TV show Last Day of Pompeii

“Elsewhere there was daylight by this time, but they were still in darkness, blacker and denser than any ordinary night, which they relieved by lighting torches and various kinds of lamp. My uncle decided to go down to the shore and investigate on the spot the possibility of any escape by sea, but he found the waves still wild and dangerous. A sheet was spread on the ground for him to lie down, and he repeatedly asked for cold water to drink. Then the flames and smell of sulphur which gave warning of the approaching fire drove the others to take flight and roused him to stand up. He stood leaning on two slaves and then suddenly collapsed, I imagine because the dense fumes choked his breathing by blocking his windpipe which was constitutionally weak and narrow and often inflamed. When daylight returned on the 26th—two days after the last day he had seen—his body was found intact and uninjured, still fully clothed and looking more like sleep than death.”

Pliny the Younger’s Letter 6.20 on the Vesuvius Eruption

Pliny the Younger (A.D. 61- 113) wrote to to Cornelius Tacitus in Letter 6.20: “So the letter which you asked me to write on my uncle's death has made you eager to hear about the terrors and hazards I had to face when left at Misenum, for I broke off at the beginning of this part of my story. "Though my mind shrinks from remembering…I will begin. After my uncle's departure I spent the rest of the day with my books, as this was my reason for staying behind. Then I took a bath, dined, and then dozed fitfully for a while. For several days past there had been earth tremors which were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania: but that night the shocks were so violent that everything felt as if it were not only shaken but overturned. My mother hurried into my room and found me already getting up to wake her if she were still asleep. [Source: Pliny the Younger (A.D. 61- 113). Letters 6.16 and 6.20, From Penguin translation by Betty Radice]

“By now it was dawn, but the light was still dim and faint. The buildings round us were already tottering, and the open space we were in was too small for us not to be in real and imminent danger if the house collapsed. This finally decided us to leave the town. We were followed by a panic-stricken mob of people wanting to act on someone else’s decision in preference to their own (a point in which fear looks like prudence), who hurried us on our way by pressing hard behind in a dense crowd. Once beyond the buildings we stopped, and there we had some extraordinary experiences which thoroughly alarmed us. The carriages we had ordered to be brought out began to run in different directions though the ground was quite level, and would not remain stationary even when wedged with stones. We also saw the sea sucked away and apparently forced back by the earthquake: at any rate it receded from the shore so that quantities of sea creatures were left stranded on dry sand. On the landward side a fearful black cloud was rent by forked and quivering bursts of flame, and parted to reveal great tongues of fire, like flashes of lightning magnified in size.

“At this point my uncle’s friend from Spain spoke up still more urgently: "If your brother, if your uncle is still alive, he will want you both to be saved; if he is dead, he would want you to survive him—why put off your escape?" We replied that we would not think of considering our own safety as long as we were uncertain of his. Without waiting any longer, our friend rushed off and hurried out of danger as fast as he could.

“Soon afterwards the cloud sank down to earth and covered the sea; it had already blotted out Capri and hidden the promontory of Misenum from sight. Then my mother implored, entreated and commanded me to escape the best I could—a young man might escape, whereas she was old and slow and could die in peace as long as she had not been the cause of my death too. I refused to save myself without her, and grasping her hand forced her to quicken her pace. She gave in reluctantly, blaming herself for delaying me. Ashes were already falling, not as yet very thickly. I looked round: a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood. "Let us leave the road while we can still see," I said, "or we shall be knocked down and trampled underfoot in the dark by the crowd behind." We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room. You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore. There were people, too, who added to the real perils by inventing fictitious dangers: some reported that part of Misenum had collapsed or another part was on fire, and though their tales were false they found others to believe them. A gleam of light returned, but we took this to be a warning of the approaching flames rather than daylight. However, the flames remained some distance off; then darkness came on once more and ashes began to fall again, this time in heavy showers. We rose from time to time and shook them off, otherwise we should have been buried and crushed beneath their weight. I could boast that not a groan or cry of fear escaped me in these perils, had I not derived some poor consolation in my mortal lot from the belief that the whole world was dying with me and I with it.

“Soon afterwards the cloud sank down to earth and covered the sea; it had already blotted out Capri and hidden the promontory of Misenum from sight. Then my mother implored, entreated and commanded me to escape the best I could—a young man might escape, whereas she was old and slow and could die in peace as long as she had not been the cause of my death too. I refused to save myself without her, and grasping her hand forced her to quicken her pace. She gave in reluctantly, blaming herself for delaying me. Ashes were already falling, not as yet very thickly. I looked round: a dense black cloud was coming up behind us, spreading over the earth like a flood. "Let us leave the road while we can still see," I said, "or we shall be knocked down and trampled underfoot in the dark by the crowd behind." We had scarcely sat down to rest when darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night, but as if the lamp had been put out in a closed room. You could hear the shrieks of women, the wailing of infants, and the shouting of men; some were calling their parents, others their children or their wives, trying to recognize them by their voices. People bewailed their own fate or that of their relatives, and there were some who prayed for death in their terror of dying. Many besought the aid of the gods, but still more imagined there were no gods left, and that the universe was plunged into eternal darkness for evermore. There were people, too, who added to the real perils by inventing fictitious dangers: some reported that part of Misenum had collapsed or another part was on fire, and though their tales were false they found others to believe them. A gleam of light returned, but we took this to be a warning of the approaching flames rather than daylight. However, the flames remained some distance off; then darkness came on once more and ashes began to fall again, this time in heavy showers. We rose from time to time and shook them off, otherwise we should have been buried and crushed beneath their weight. I could boast that not a groan or cry of fear escaped me in these perils, had I not derived some poor consolation in my mortal lot from the belief that the whole world was dying with me and I with it.

“At last the darkness thinned and dispersed into smoke or cloud; then there was genuine daylight, and the sun actually shone out, but yellowish as it is during an eclipse. We were terrified to see everything changed, buried deep in ashes like snowdrifts. We returned to Misenum where we attended to our physical needs as best we could, and then spent an anxious night alternating between hope and fear. Fear predominated, for the earthquakes went on, and several hysterical individuals made their own and other people’s calamities seem ludicrous in comparison with their frightful predictions. But even then, in spite of the dangers we had been through, and were still expecting, my mother and I had still no intention of leaving until we had news of my uncle.”

Archaeological Areas of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata

According to UNESCO: “When Vesuvius erupted on 24 August A.D. 79, it engulfed the two flourishing Roman towns of Pompei and Herculaneum, as well as the many wealthy villas in the area. These have been progressively excavated and made accessible to the public since the mid-18th century. The vast expanse of the commercial town of Pompei contrasts with the smaller but better-preserved remains of the holiday resort of Herculaneum, while the superb wall paintings of the Villa Oplontis at Torre Annunziata give a vivid impression of the opulent lifestyle enjoyed by the wealthier citizens of the Early Roman Empire. [Source: UNESCO World Heritage Site website =]

“Herculaneum was rediscovered in 1738 and Pompeii in 1748. By the mid-eighteenth century, when scholars made the journey to Naples and reported on the findings, the imagination of Europe was ignited. Suddenly, the classical world was in vogue. Philosophy, art, architecture, literature, and even fashion drew upon the discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum for inspiration; the Neoclassical movement was under way.

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine:“Since 1748, when a team of Royal Engineers dispatched by the King of Naples began the first systematic excavation of the ruins, archaeologists, scholars and ordinary tourists have crowded Pompeii’s cobblestone streets for glimpses of quotidian Roman life cut off in medias res, when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius suffocated and crushed thousands of unlucky souls. From the amphitheater where gladiators engaged in lethal combat, to the brothel decorated with frescoes of couples in erotic poses, Pompeii offers unparalleled glimpses of a distant time. “Many disasters have befallen the world, but few have brought posterity so much joy,” Goethe wrote after touring Pompeii in the 1780s.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian Magazine, July 2015 ~|~]

Pompeii Victim Died from Earthquakes, Not Just Volcanic Ash

Victims who died in Pompeii after the A.D. 79 Vesuvius eruption may have been killed by a simultaneous earthquake, according to research published in July 2024. AFP reported: Scholars have debated for decades whether seismic activity occurred during the eruption of Vesuvius ago, and not just before it, as reported by Pliny the Younger. [Source AFP, July 19, 2024]

The article published in the academic journal "Frontiers in Earth Science" takes a new look at the disaster, arguing that one or more concurrent earthquakes were "a contributing cause of building collapse and death of the inhabitants". "Our conclusions suggest that the effects of the collapse of buildings triggered by syn-eruptive seismicity (seismic activity at the time of an eruption) should be regarded as an additional cause of death in the ancient Pompeii," it said.

In May 2023, archaeologists uncovered the skeletons of two men who appeared to have been killed not by heat and clouds of fiery gas and ash but from trauma due to collapsed walls — providing precious new data. One of the victims was discovered with his left hand raised, as if to protect his head. "It is worth noting that such traumas are analogous to those of individuals involved in modern earthquakes," wrote the authors, who determined that the collapsed walls were not due to falling stones and debris but to seismic activity. "In a broader view that takes into account the whole city, we consider, as a working hypothesis, that the casualties caused by seismically triggered building failures may not be limited to the two individuals," the authors wrote.

Did A Man Really Discover Pliny the Elder’s Skull?

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: “In the early 1900s, an intrepid engineer named Gennaro Matrone discovered a cluster of seventy-three skeletons during a private excavation in Stabiae. One of these skeletons was set apart from the others and was found wearing a heavy gold chain, three rings, and small collection of bracelets. It was discovered still clutching an ornately decorated sword. Matrone claimed that he might have discovered the remains of Pliny the Elder. At the time, however, scholars were skeptical about the discovery and outright ridiculed Matrone. The engineer ended up selling the jewelry and burying most of the human remains but kept a portion of ‘Pliny’ and eventually bequeathed them to a museum. Now, new DNA analysis of the parts of the skeleton Matrone kept (the skull, jawbone, and sword) reveals that he might have been right after all.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, February 9, 2020]

After gathering figurative dust at the fabulous Museo Storico Nazionale dell'Arte Sanitaria (National Historic Museum of Healthcare Art) in Rome, the skull and jawbone were recently re-examined by anthropologists. The results, which were presented last month in Rome and reported on in La Stampa and Livescience, show that the skull (though not the jaw) might plausibly have come from Pliny.

Analysis of ash that had adhered to the surface of the skull proved that the individual had died during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Further examination of the skull revealed that it came from someone aged between 48 and 65. The jawbone, however, came from someone much younger. Luciano Fattore, a freelance anthropologist who worked on the project, speculated to Livescience that perhaps Matrone had found the jawbone near to the skull and assumed that they came from the same person.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024