Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

ROME AS AN ANCIENT IMPERIAL CAPITAL

Rome was surrounded the Aurelian Wall, which reached a length of 18.8 kilometers (11.7 miles) and enclosed an area of about about 14 square kilometers. Like all the Greek and Latin cities of antiquity, ancient Rome, from the dawn of her legend to the end of her history, had always consisted of two inseparable elements, a sharply defined urban agglomeration (Urbs Roma) and the rural territory attached to it (Ager Romanus). The Ager Romanus extended to the boundaries of the adjacent cities, which had preserved their municipal individuality in spite of political annexation; Lavinium, Ostia, Fregenae, Veii, Fidenae, Ficulea, Gabii, Tibur, and Bovillae. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The Urbs proper was the home of the gods and their sanctuaries, of the king, and later of the magistrates who were heirs to his dismembered power, of the Senate and the comitia who, in co-operation first with the king and later with the magistrates, governed the City-State. Thus in its origins the city represented something greater and different from a more or less closely packed aggregate of dwelling houses : it was a templum solemnly dedicated according to rites prescribed by the discipline of the augurs, its precincts strictly defined by the furrow which the Latin founder, dutifully obeying the prescriptions of Etrurian ritual, had carved round it with a plough drawn by a bull and cow of dazzling white.

The geographer Strabo (64 B.C.- A.D. 21) wrote in “Geography”, V.iii (A.D. c. 20) in the Age of Agustus: “Roman prudence was more particularly employed on matters which have received but little attention from the Greeks — such as paving their roads, constructing aqueducts, and sewers. In fact they have paved the roads, cut through hills, and filled up valleys, so that the merchandise may be conveyed by carriage from the ports. The sewers, arched over with hewn stones, are large enough in parts for actual hay wagons to pass through, while so plentiful is the supply of water from the aqueducts, that rivers may be said to flow through the city and the sewers, and almost every house is furnished with water pipes and copious fountains. [Source: Strabo (64/3 B.C.- A.D. c.21): “Geography”, V.iii A.D. c. 20, William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 232-237]

“We may remark that the ancients [of Republican times] bestowed little attention upon the beautifying of Rome. But their successors, and especially those of our own day, have at the same time embellished the city with numerous and splendid objects. Pompey, the Divine Caesar [i.e. Julius Caesar], and Augustus, with his children, friends, wife, and sister have surpassed all others in their zeal and munificence in these decorations. The greater number of these may be seen in the Campus Martius which to the beauties of nature adds those of art. The size of the plain is remarkable, allowing chariot races and the equestrian sports without hindrance, and multitudes [here] exercise themselves with ball games, in the Circus, and on the wrestling grounds. The structures that surround [the Campus], the greensward covered with herbage all the year around, the summit of the hills beyond the Tiber, extending from its banks with panoramic effect, present a spectacle which the eye abandons with regret.

“Near to this plain is another surrounded with columns, sacred groves, three theaters, an amphitheater, and superb temples, each close to the other, and so splendid that it would seem idle to describe the rest of the city after it. For this cause the Romans esteeming it the most sacred place, have erected funeral monuments there to the illustrious persons of either sex. The most remarkable of these is that called the "Mausoleum" [the tomb of Augustus] which consists of a mound of earth raised upon a high foundation of white marble, situated near the river, and covered on the top with evergreen shrubs. Upon the summit is a bronze statue of Augustus Caesar, and beneath the mound are the funeral urns of himself, his relatives, and his friends. Behind is a large grove containing charming promenades. In the center of the plain [the Campus Martius] is the spot where [the body of] this prince was reduced to ashes. It is surrounded by a double enclosure, one of marble, the other of iron, and planted within with poplars. If thence you proceed to visit the ancient Forum, which is equally filled with basilicas, porticoes, and temples, you will there behold the Capitol, the Palatine, and the noble works that adorn them, and the piazza of Livia [Augustus's Empress], each successive work causing you speedily to forget that which you have seen before. Such then is Rome!

“In Rome there is continual need of wood and stone for ceaseless building caused by the frequent falling down of houses, and on account of conflagrations and of sales which seem never to cease. These sales are a kind of voluntary falling-down of houses, each owner knocking down and rebuilding according to his individual taste. For these purposes the numerous quarries, forests, and rivers in the region which convey the materials, offer wonderful facilities.

“Augustus Caesar endeavored to avert from the city the dangers alluded to, and instituted a company of freedmen, who should be ready to lend their assistance in the ease of conflagration, while as a preventive against falling houses he decreed that all new buildings should not be carried to the same height as formerly, and those erected along the public ways should not exceed seventy feet in height. But these improvements must have ceased except for the facilities afforded to Rome by the quarries, the forests, and the ease of transport.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

BUILDINGS IN ANCIENT ROME CITY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CITIES, TOWNS AND URBAN LIFE IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ;

POMPEII europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HERCULANEUM europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Eternal City: A History of Rome in Maps”

by Jessica Maier (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City” (Two Volumes) by Andrea Carandini (2017) Amazon.com;

“City: A Story of Roman Planning and Construction” by David Macaulay (1983) Amazon.com;

“Early Rome to 290 BC: The Beginnings of the City and the Rise of the Republic” by Guy Bradley (2020) Amazon.com;

“Rome: The Center of Power, 500 B.C. to A.D. 200" by Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, translated by Peter Green Amazon.com;

“Ancient Rome in Fifty Monuments” by Paul Roberts Amazon.com;

“Hadrian and the City of Rome” by Mary Taliaferro Boatwright Amazon.com;

“The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome” by J. Bert Lott (2004) Amazon.com

“The Ancient City” by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1864) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in the Roman City: Rome, Pompeii, and Ostia” by Gregory S. Aldrete (2009) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Rome: City Planning and Administration"

by O. F. Robinson Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy: Toilets, Sewers, and Water Systems”

by Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow (2018) Amazon.com;

“Public Toilets (Foricae) and Sanitation in the Ancient Roman World: Case Studies in Greece and North Africa” by Antonella Patricia Merletto (2023) Amazon.com;

“24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There” by Philip Matyszak (2017) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Pliny the Elder on the Layout of Rome

William Stearns Davis wrote:“The following short sketch of Rome, its streets, buildings, etc., is given us by a careful author, writing in the reign of Vespasian (69-79 A.D.). While the area of Rome was far inferior to various great modern capitals, probably the masses of the population were so compactly housed that the inhabitants in Pliny's time numbered well up to 1,500,000, although any estimates must be very uncertain.”

Pliny the Elder wrote in “Natural History” III.v.66-67: “Romulus left the city of Rome, if we are to believe those who state the very greatest number, with only three gates, and no more. When the Vespasians' were Emperors and Censors in the year of the building of the city, 826 [73 CE], the circumference of the walls which surrounded it was thirteen and two-fifths miles. Surrounding as it does the Seven Hills, the city is divided into fourteen districts, with 265 crossroads under the guardianship of the Lares [i.e., a little shrine to the Lares would stand at each crossing]. [Source: Pliny the Elder (23/4-79 A.D.), “The Grandeur of Rome”, from Natural History, III.v.66-67, NH XXXVI.xxiv.101-110, NH XXXVI.xxiv.121-123. (A.D. c. 75) , William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 179-181, 232-237]

“If a straight line is drawn from the mile column placed at the entrance of the Forum to each of the gates, which are at present thirty-seven in number — taking care to count only once the twelve double gates, and to omit the seven old ones, which no longer exist — the total result will be a straight line of twenty miles and 765 paces. But if we draw a straight line from the same mile column to the very last of the houses, including therein the Praetorian camp [in the suburbs] and follow throughout the line of the streets, the result will be something over seventy miles. Add to these calculations the height of the houses, and then a person may form a fair idea of this city, and surely he must confess that no other place in the world can vie with it in size.

“On the eastern side it is bounded by the mound (agger) of Tarquinius Superbus — a work of surpassing grandeur; for he raised it so high as to be on a level with the walls on the side on which the city lay most exposed to attack from the neighboring plains. On all the other sides it has been fortified either with lofty walls, or steep and precipitous hills; yet it has come to pass, that the buildings of Rome — increasing and extending beyond all bounds — have now united many outlying towns to it.

Model of the area around the Pantheon in ancient Rome

Pomerium — City Limits of Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome, the pomerium was a consecrated piece of land along the city walls, where it was forbidden to farm, live or build. Roman legend holds that Romulus, the city’s mythical founder, created the original pomerium in the eighth century B.C. around his fledgling settlement. The area was marked by sacred stones called "cippi." As the city grew, the pomerium was extended and new cippi were added to delineate it. The pomerium was a hallowed zone where activities were dictated by a strict set of rules. For example, no one could be buried within its limits. This symbolic barrier was the border between Rome proper — the urbs — and its outlying territory — the ager — and separated religious activities from civic and military life. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2022]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Breaking conventions inside the pomerium was considered a serious offense to the gods. No weapons were allowed there, although priests gave dispensations for the bodyguards of magistrates and soldiers taking part in one of the many "triumphs" granted by the Roman senate xxa name that meant "old men" and was a ruling assembly of hundreds of the wealthiest citizens — to military commander or emperor who'd won a victory. [Source Tom Metcalfe Live Science, August 23, 2022]

In particular, magistrates of the city — the officers elected for a year for various tasks, including the consuls who held the highest posts in the Roman Republic — were required to consult what were called the city auspices ("auspicia urbana") whenever they crossed the pomerium. This was a small ceremony by a priest, supposedly foretelling good or bad luck, which according to the superstition could be fatal to neglect. The Roman politician and author Cicero relates that in 163 B.C. the consul Tiberius Gracchus forgot to take the city auspices a second time after crossing the pomerium twice in the same day and that his failure led to the sudden death of an official who was collecting votes.

In July 2021, archaeologists announced they had discovered a cippie stone that dated from the age of Emperor Claudius in A.D. 49 and was found during excavations for a new sewage system under the recently restored mausoleum of Emperor Augustus, right off the central Via del Corso in Rome’s historic center. According to Archaeology magazine The six-foot-tall limestone block was found embedded in the ground where it had been placed almost 2,000 years ago and is one of only 10 of its kind ever discovered. The marker was one of dozens that were installed around the city to mark the pomerium.

Pomerium and Field of Mars

The pomerium separated the area of domi (at home, at peace) and militiae (the area of warfare and the unlimited power of the war leader). According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: Rome included sectors outside the pomerial zone that were still part of the city: the Aventine Hill, which had been outside the city of the four regions (its incorporation into the city was attributed by tradition sometimes to Romulus and sometimes to Ancus Marcius), remained outside the pomerial zone until the time of Claudius (first century ce), even though it was surrounded by what was called "Servius's wall." [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005),Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The same extrapomerial status held true for the Field of Mars, which owed its name to the military exercises that were conducted on its esplanade. Yet here there occurs a further practice that lies at the root of Roman law. On this emplacement there was an altar consecrated to Mars from time immemorial. It is mentioned by the "royal" law of Numa in relation to the distribution of the spolia opima (spoils taken from an enemy's general slain by one's own army commander) and was completed later by the erection of a temple in 138 B.C. The assemblies of military centuries (comitia centuriata) were also held there. In addition, every five years the purification of the people (lustrum) was celebrated on the Field of Mars by the sacrifice of the suovetaurilia, the set of three victims — boar, ram, and bull — that had been paraded beforehand around the assembly of citizens.

The presence of the old Mars outside the pomerium (similarly, another temple of Mars, constructed in 338 B.C. to the south of Rome outside the Porta Capena, was also outside the pomerial zone) was in strict conformity with the distinction established between the imperium domi, the jurisdiction of civil power circumscribed by the pomerial zone, and the imperium militiae that could not show itself except outside this zone. This is why it was necessary to take other auspices when one wanted to go from one zone to another. If one failed to do so, every official act was nullified. This misfortune befell the father of the Gracchi, T. Sempronius Gracchus, during his presidency of the comitia centuriata. While going back and forth between the Senate and the Field of Mars, he forgot to take the military auspices again; as a result, the election of consuls that took place in the midst of the assemblies when he returned was rejected by the Senate (see Cicero, De divinatione 1.33 and 2.11). The delimitation of Roman sacral space by the pomerial line explains the distribution of the sanctuaries. Vesta, the goddess of the public hearth, could only be situated at the heart of the city within the pomerium, whereas a new arrival, such as Juno Regina, originating in Veii, was received, as an outsider, in a temple built on the Aventine (in 392 B.C.).

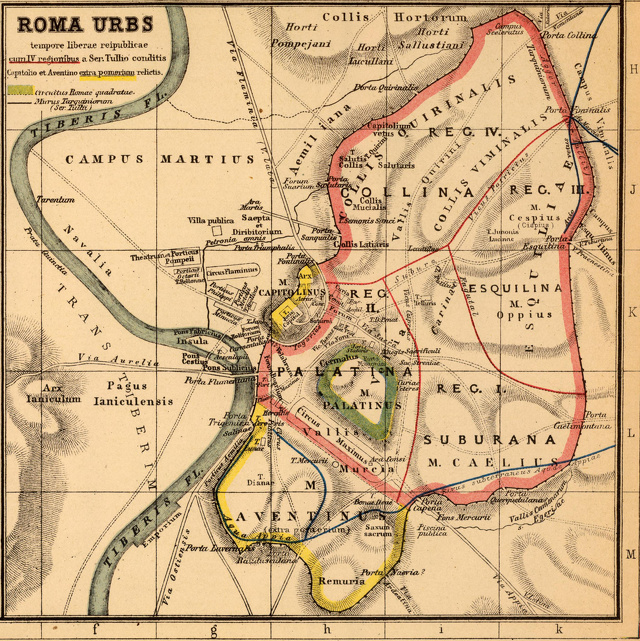

Map of Rome during the Roman Republic: the pomerium is marked in pink; the Capitoline and Aventine are extra pomerium, 'beyond the wall'; their boundaries are in yellow

Districts and Quarters of the City of Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome, the city, an equalitarian instinct had always tended to place the most stately dwellings and the humblest side by side.This brotherly feature of the living Rome helps us to reconstruct in imagination the Rome of the Caesars where high and low, patrician and plebeian, rubbed shoulders everywhere without coming into conflict. Haughty Pompey did not consider it beneath his dignity to remain faithful to the Carinae. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Before migrating for political and religious reasons info the precincts of the Regia, the most fastidicus of patricians, Julius Caesar, lived in the Subura. Later Maecenas planted his gardens in the most evilly reputed part of the Esquiline. About the same period the ultra-wealthy Asinius Pollio chose for his residence the plebeian Aventine, where Licinius Sura, vice emperor of the reign of Trajan, also elected to make his home. At the end of the first century A.D. the emperor Vespasian's nephew and a parasite poet like Martial were near neighbours on the slopes of the Quirinal, and at the end of the second century Commodus went to dwell in a gladiatorial school on the Caelian.

It is true that when they were laid waste by fire the various quarters of the city rose from their ashes more solid and more magnificent than before. Nevertheless, the incongruous juxtapositions which persist to this day were repeated with a minimum of change after each renovation, and every attempt to specialise the fourteen regions of the Urbs was foredoomed to failure. Hypersensitive people, anxious to escape the mob, were driven to move to a greater and greater distance, to take refuge on the fringes of the Campagna among the pines of the Pincian or the Janiculum, where they could find room for the parks of their suburban villas.

The common people, meanwhile, driven out of the center of the city by the presence of the court and the profusion of public buildings but nevertheless fettered to it by the business transacted there, overflowed by preference into the zones intermediate between the fora and the outskirts, the outside districts adjacent to the Republican Wall, which the reform of Augustus had with one stroke of the pen incorporated in the Urbs. The Regionaries record the number of insulac or apartment blocks in each region, and the number of vici or arteries serving the insulae; and separate averages may be obtained for the eight regions of the old city and the six regions of the new. The average for the older regions is 2,965 insulae with 17 vici and for the newer 3,429 insulac with 28 vici. We note that the largest number of insulae were massed in the new city; and that they attained the greatest size not in the old city where there were 174 insulae per vicus, but in the new where there were only 123 per vicus. The Regionaries also locate for us the Insula of Felicula, the giant sky-scraper in the ninth region, known as the region of the Circus Flaminius, in the very heart of the new city. Isolated soundings lead us to the same conclusion as do mass statistics: the successful experiments of imperial city planning caused the huge modern-style apartment blocks of ancient Rome to increase in. number and grow to immoderate size.

City Life in Ancient Rome City

Only people of consequence with well-lined purses could indulge in the luxury of such a domus. We know for instance that in Caesar's day Caelius paid for his annual rent of 30,000 sesterces ($1,200.00). In the humbler insulae the ground floor might be divided into booths and shops, the tabernae, which we can visualize the better because the skeletons of many have survived to this day in the Via Biberatica and at Ostia. Above the tabernae lowlier folk were herded. Each taberna opened straight onto the street by a large arched doorway extending its full width, with folding wooden leaves which were closed or drawn across the threshold every evening and firmly locked and bolted. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Each represented the storehouse of some merchant, the workshop of some artisan, or the counter and show-window of some retailer. But in the corner of each taberna there was nearly always a stair of five or six steps of stone or brick continued by a wooden ladder. The ladder led to a sloping loft, lit directly by one long oblong window pierced above the center of the doorway, which served as the lodging of the storekeeper, the caretakers of the shop, or the workshop hands. Whoever they might be, the tenants of tabernae had never more than this one room for themselves and their families: they worked, cooked, ate, and slept there, and were at least as crowded as the tenants of the upper floors. Perhaps on the whole they were even worse provided for. Certainly they frequently found genuine difficulty in meeting their obligations. To bring pressure to bear on a defaulter, the landlord might "shut up the tenant". that is, make a lien on his property to cover the amount due.'

There were, then, differences between the two types of apartment house which are known by the common name of insula, but almost all resulted from the primary distinction between those houses where the rez-de-chaussee formed a domus and those in which it was let out in tabrnae. The two types might be found side by side, and they obeyed the same rules in the internal arrangement and external appearance of their upper stories.

Crowded Ancient Rome

Even assessing the area of the Urbs at more than 2,000 hectares, the circuit of the Imperial City was too limited to accommodate 1,200,000 inhabitants, comfortably especially since every part of it could not be used for housing. We must subtract the numerous zones where public buildings, sanctuaries, basilicas, docks, baths, circuses, and theaters were in the hands of public authorities, who permitted only a handful of persons to live in them, such as porters, bonders, clerks, beadles, public slaves, or members of certain privileged corporations. We must exclude the capricious bed of the Tiber and the forty or so parks and gardens which stretched along the Esquiline, the Pincian, and both banks of the river; the Palatine Hill, which was reserved exclusively for the emperor's enjoyment; and finally the Campus Martius, whose temples, porticos, palaestrae, ustrinae, and tombs covered more than two hundred hectares, from most of which all human habitations were banished in deference to the gods. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Now we must remember that the ancient Romans had no access to the almost unlimited suburban space which overground and underground transport puts at the disposal of London, Paris, and New York. They were condemned to remain within closer territorial limits owing to a lack of technical skill which strictly limited the space at their command; and they were unable to increase the area of their city in proportion to the numerical increase of their population. They were driven to compensate for this lack of room by two contradictory expedients: narrow streets and tall houses.

Imperial Rome was continually forced to juxtapose her splendid monuments to an incoherent confusion of dwelling — houses at once pretentious and uncomfortable, fragile and inordinately large, separated by a network of gloomy, narrow alleys. When we try to reconstruct ancient Rome in our imagination, we are ever and again disconcerted by the contrast of modern spaciousness with primitive mediaeval simplicity, an anticipation of orderliness that is almost American with the confusion of an oriental labyrinth.

Streets in the Ancient City of Rome

If the disentangled the jumble of the Roman streets were laid end to end, they would have covered a distance of 60,000 passus, or approximately 89 kilometers according to the calculations and measurements carried out by the censors Vespasian and Titus in 73 A.D. When we consider the actual layout of Roman streets, we find them forming an inextricably tangled net, their disadvantages immensely aggravated by the vast height of the buildings which shut them in. Tacitus attributes the ease and speed with which the terrible fire of 64 A.D. spread through Rome to the anarchy of these confined streets, winding and twisting as if they had been drawn haphazard between the masses of giant insulae. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The streets always smacked of their ancient origin and maintained the old distinctions which had prevailed at the time of their rustic development: the semita which were tracks only for men on foot, the actus, which permitted the passage of only one cart at a time, and finally the viae proper, which permitted two carts to pass each other or to drive abreast. Among all the innumerable streets of Rome, only two inside the old Republican Wall could justly claim the name of via. They were the Via Sacra and the Via Nova, which respectively crossed and flanked the Forum, and the insignificance of these two thoroughfares remains a perpetual surprise. Between the gates of the innermost enclosure and the outskirts of the fourteen regions, not more than a score of others de erved the title : the roads which led out of Rome to Italy, the Via Appia, the Via Latina, the Via Ostiensis, the Via Labicana, etc. They varied in width from 4.80 to 6.50 meters, a proof that they had not been greatly enlarged since the day when the Twelve Tables had prescribed a maximum width of 4.80 meters.

The majority of the other thoroughfares, the real streets, or vici, scarcely attained this last figure and many fell far below it, being simple passages (angiportus) or tracks (semitae) which had to be at least 2.9 meters wide to allow for projecting balconies. Their narrowness was all the more inconvenient in that they constantly zigzagged and on the Seven Hills rose and fell steeply hence the name of clivi which many of them, like the Clivus Capitolinus, the Clivus Argentarius, bore of good right. They were daily defiled by the filth and refuse of the neighbouring houses, and were neither so well kept as Caesar had decreed in his law, nor always furnished with the foot-paths and paving that he had also prescribed.

Caesar's celebrated text, graven on the bronze tablet of Heraclea, is worth rereading. In comminatory words he commands the landlords whose buildings face on a public street to clean in front of the doors and walls, and orders the aediles in each quarter to make good any omission by getting the work done through a contractor for forced labour, appointed in the usual manner of state contractors, at a fee fixed by preliminary bidding, which the delinquent will be obliged forthwith to pay. The slightest delay in payment is to be visited by exaction of a double fee. The command is imperative, the punishment merciless. But ingenious as was the machinery for carrying it out, this procedure involved a delay of ten days at least which must have usually defeated its purpose, and it cannot be denied that gangs of sturdy sweepers and cleaners directly recruited and employed by the aediles would have disposed of the business more promptly and more satisfactorily. We have, however, no indication that this was ever done, and the idea that in this case the State should have taken the authority and responsibility off the shoulders of the private individual could not possibly have entered the head of any Roman, though he were gifted with the genius of a Julius Caesar.

If the streets of Imperial Rome had been as generally paved as they suppose, the Flavian praetor of whom Martial writes would not have been obliged to "walk right through the mud" in using them nor would Juvenal in his turn have had his legs caked with mud. As for foot-paths, it is impossible that they lined the streets, which were becoming completely submerged under the rising tide of outspread merchandise until Domitian intervened with an edict forbidding the display of wares on the street. His edict is commemorated in the epigram: "Thanks to you, Germanicus, no pillar is now girt with chained flagons,... nor does the grimy cook-shop monopolise the public way. Barber, tavern-keeper, cook, and butcher keep within their own threshold. Now Rome exists, which so recently was one vast shop."

At night when there was no moon its streets were plunged in impenetrable darkness. No oil lamps lighted them, no candles were affixed to the walls; no lanterns were hung over the lintel of the doors, save on festive occasions. In normal times night fell over the city like the shadow of a great danger, diffused, sinister, and menacing. Everyone fled to his home, shut himself in, and barricaded the entrance. The shops fell silent, safety chains were drawn across behind the leaves of the doors; the shutters of the flats were closed and the pots of flowers withdrawn from the windows they had adorned. If the rich had to sally forth, they were accompanied by slaves who carried torches to light and protect them on their way. Other folk placed no undue reliance on the night watchmen (sebaciarii), squads of whom, torch in hand, patrolled the sector too vast to be completely guarded.

Juvenal sighs that to go out to supper without having made your will was to expose yourself to the reproach of carelessness; and if his satire goes too far in contending that the Rome of his day was more dangerous than the forest of Gallinaria or the Pontine marshes, we need only to turn the leaves of the Digest and note the passages which render liable to prosecution by the praefectus vigilum the murderers (sicarii), the housebreakers (effractores), the footpads of every kind (raptores) who abounded in the city, in order to admit that "many misadventures were to be feared" in her pitch-dark vici, where in Sulla's day Roscius of Ameria met his death.

Water Supply and Aqueducts in Rome and Roman Cities

The site of Rome itself was well supplied with water. Springs were abundant, and wells could be sunk to find water at no great depth. Rain water was collected in cisterns, and the water from the Tiber was used. But these sources came to be inadequate, and in 312 B.C. the first of the great aqueducts (aquae) was built by the famous censor, Appius Claudius, and named for him the Aqua Appia. It was eleven miles long, of which all but three hundred feet was underground. This and the Anio Vetus, built forty years later, supplied the lower levels of the city. The first high-level aqueduct, the Marcia, was built by Quintus Marcius Rex, to bring water to the top of the Capitoline Hill, in 140 B.C. Its water was and still is particularly cold and good. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

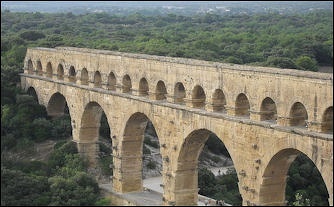

Roman aqueduct

“The Tepula, named from the temperature of its waters, and completed in 125 B.C., was the last built during the Republic. Under Augustus three more were built, the Julia and the Virgo by Agrippa, and the Alsietina by Augustus, for his naumachia. The Claudia, whose ruined arches are still a magnificent sight near Rome, and the Anio Novus were begun by Caligula and finished by Claudius. The Traiana was built by Trajan in 109 A.D., and the last, the Alexandrina, by Alexander Severus. Eleven aqueducts then served ancient Rome. Modern Rome is considered unusually well supplied with water from four, using the sources and occasionally the channels of as many of the ancient ones. The Virgo, now Acqua Vergine, was first restored by Pius V in 1570. The springs of the Alexandrina supply the Acqua Felice, built in 1585. The Aqua Traiana was restored as the Acqua Paola in 1611. The famous Marcia was reconstructed in 1870 as the Acqua Pia, or Marcia-Pia.

“The channels of the aqueducts were generally built of masonry, for lack of sufficiently strong pipes. Cast-iron pipes the Romans did not have, lead was rarely used for large pipes, and bronze would have been too expensive. Because of this lack, and not because they did not understand the principle of the siphon, high pressure aqueducts were less commonly constructed. To avoid high pressure, the aqueducts that supplied Rome with water, and many others, were built at a very easy slope and frequently carried around hills and valleys, though tunnels and bridges were sometimes used to save distance. The great arches, so impressive in their ruins, were used for comparatively short distances, as most of the channels were underground. |+|

“In the cities the water was carried into distributing reservoirs (castella), from which ran the street mains. Lead pipes (fistulae) carried the water into the houses. These pipes were made of strips of sheet lead with the edges folded together and welded at the joining, thus being pear-shaped rather than round. As these pipes were stamped with the name of the owner and user, the finding of many at Rome in our own time has made it possible to locate the sites of the residences of many distinguished Romans. In Pompeii these pipes can be seen easily now, for in that mild climate they were often laid on the ground close to the house, not buried as in most parts of this country. The poor must have carried the water that they used from the public fountains that were placed at frequent intervals in the streets, where the water ran constantly for all comers.” |+|

Pliny the Elder on the Sewers and Aqueducts of Rome

Pliny the Elder wrote in “Natural History” History XXXVI.xxiv.101-110: ““Frequently praise is given to the great sewer system of Rome. There are seven "rivers" made to flow, by artificial channels, beneath the city. Rushing onward like so many impetuous torrents, they are compelled to carry off and sweep away all the sewerage; and swollen as they are by the vast accession of the rain water, they reverberate against the sides and bottoms of their channels. Occasionally too the Tiber, overflowing, is thrown backward in its course, and discharges itself by these outlets. Obstinate is the struggle that ensues between the meeting tides, but so firm and solid is the masonry that it is able to offer an effectual resistance. Enormous as are the accumulations that are carried along above, the work of the channels never gives way. Houses falling spontaneously to ruins, or leveled with the ground by conflagrations are continually battering against them; now and then the ground is shaken by earthquakes, and yet — built as they were in the days of Tarquinius Priscus, seven hundred years ago — these constructions have survived, all but unharmed.” [Source: Pliny the Elder (23/4-79 A.D.), “The Grandeur of Rome”, from Natural History, III.v.66-67, NH XXXVI.xxiv.101-110, NH XXXVI.xxiv.121-123. (A.D. c. 75) , William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 179-181, 232-237]

lead pipes

Pliny the Elder wrote in “Natural History” XXXVI.xxiv.121-123: “But let us now turn our attention to some marvels that, if justly appreciated, may be pronounced to remain unsurpassed. Quintus Marcius Rex [praetor in 144 B.C.] upon being commanded by the Senate to repair the Appian Aqueduct and that of the Anio, constructed during his praetorship a new aqueduct that bore his name, and was brought hither by a channel pierced through the very sides of mountains. Agrippa, during his aedileship, united the Marcian and the Virgin Aqueducts and repaired and strengthened the channels of others. He also formed 700 wells, in addition to 500 fountains, and 130 reservoirs, many of them magnificently adorned. Upon these works too he erected 300 statues of marble or bronze, and 400 marble columns, and all this in the space of a single year! In the work which he has written in commemoration of his aedileship, he also informs us that public games were celebrated for the space of fifty-seven days and 170 gratuitous bathing places were opened to the public. The number of these at Rome has vastly increased since his time.

“The preceding aqueducts, however, have all been surpassed by the costly work which has more recently been completed by the Emperors Gaius [Caligula] and Claudius. Under these princes the Curtian and the Caerulean Waters with the "New Anio" were brought a distance of forty miles, and at so high a level that all the hills — whereon Rome is built — were supplied with water. The sum expended on these works was 350,000,000 sesterces. If we take into account the abundant supply of water to the public, for baths, ponds, canals, household purposes, gardens, places in the suburbs and country houses, and then reflect upon the distances that are traversed from the sources on the hills, the arches that have been constructed, the mountains pierced, the valleys leveled, we must perforce admit that there is nothing more worthy of our admiration throughout the whole universe.”

Juvenal Complains About All the Foreigners in Rome

Like most Roman satirists, Juvenal wrote in from a conservative viewpoint. His Third Satire is an aggressive attack on the internationalization of the city Rome. Juvenal wrote in Satire III: On the City of Rome (A.D. c. 118): ““Since at Rome there is no place for honest pursuits, no profit to be got by honest toil — my fortune is less to-day than it was yesterday, and to-morrow must again make that little less — we purpose emigrating to the spot where Daedalus put off his wearied wings, while my grey hairs are still but few, my old age green and erect; while something yet remains for Lachesis to spin, and I can bear myself on my own legs, without a staff to support my right hand. Let us leave our native land. There let Arturius and Catulus live. Let those continue in it who turn black to white; for whom it is an easy matter to get contracts for building temples, clearing rivers, constructing harbors, cleansing the sewers, the furnishing of funerals, and under the mistress-spear set up the slave to sale. [Source: “The Satires of Juvenal, Persius, Sulpicia and Lucilius,” translated by Rev. Lewis Evans (London: Bell & Daldy, 1869), pp. 15-27]

“It is that the city is become Greek, Quirites, that I cannot tolerate; and yet how small the proportion even of the dregs of Greece! Syrian Orontes has long since flowed into the Tiber, and brought with it its language, morals, and the crooked harps with the flute-player, and its national tambourines, and girls made to stand for hire at the Circus. Go thither, you who fancy a barbarian harlot with embroidered turban. That rustic of yours, Quirinus, takes his Greek supper-cloak, and wears Greek prizes on his neck besmeared with Ceroma. One forsaking steep Sicyon, another Amydon, a third from Andros, another from Samos, another again from Tralles, or Alabanda, swarm to Esquiliae, and the hill called from its osiers, destined to be the very vitals, and future lords of great houses. These have a quick wit, desperate impudence, a ready speech, more rapidly fluent even than Isaeus. Tell me what you fancy he is? He has brought with him whatever character you wish — grammarian rhetorician, geometer, painter, trainer, soothsayer, ropedancer, physician, wizard — he knows everything. Bid the hungry Greekling go to heaven! He'll go. In short, it was neither Moor, nor Sarmatian, nor Thracian, that took wings, but one born in the heart of Athens. Shall I not shun these men's purple robes? Shall this fellow take precedence of me in signing his name, and recline pillowed on a more honorable couch than I, though imported to Rome by the same wind that brought the plums and figs? Does it then go so utterly for nothing, that my infancy inhaled the air of Aventine, nourished on the Sabine berry? Why add that this nation, most deeply versed in flattery, praises the conversation of an ignorant, the face of a hideously ugly friend, and compares some weak fellow's crane-like neck to the brawny shoulders of Hercules, holding Antaeus far from his mother Earth: and is in raptures at the squeaking voice, not a whit superior in sound to that of the cock as he bites the hen.

Gauls in Rome

“Besides, there is nothing that is held sacred by these fellows, or that is safe from their lust. Neither the mistress of the house, nor your virgin daughter, nor her suitor, unbearded as yet, nor your son, heretofore chaste. If none of these are to be found, he assails his friend's grandmother. They aim at learning the secrets of the house, and from that knowledge be feared. And since we have begun to make mention of the Greeks, pass on to their schools of philosophy, and hear the foul crime of the more dignified cloak. It was a Stoic that killed Bareas--the informer, his personal friend--the old man, his own pupil--bred on that shore on which the pinion of the Gorgonean horse lighted. There is no room for any Roman here, where some Protogenes, or Diphilus, or Erimanthus reigns supreme; who, with the common vice of his race, never shares a friend, but engrosses him entirely to himself. In exact proportion to the sum of money a man keeps in his chest, is the credit given to his oath. Though you were to swear by all the altars of the Samothracian and our own gods, the poor man is believed to despise the thunder-bolts and the gods, even with the sanction of the gods themselves. Why add that this same poor man furnishes material and grounds for ridicule to all, if his cloak is dirty and torn, if his toga is a little soiled, and one shoe gapes with its upper leather burst; or if more than one patch displays the coarse fresh darning thread, where a rent has been sewn up. Poverty, bitter though it be, has no sharper pang than this, that it makes men ridiculous. "Let him retire, if he has any shame left, and quit the cushions of the knights, that has not the income required by the law, and let these seats be taken by the sons of pimps, in whatever brothel born! Here let the son of the sleek crier applaud among the spruce youths of the gladiator, and the scions of the fencing-school.

“Who was ever allowed at Rome to become a son-in-law if his estate was inferior, and not a match for the portion of the young lady? What poor man's name appears in any will? When is he summoned to a consultation even by an aedile ? All Quirites that are poor, ought long ago to have emigrated in a body. Difficult indeed is it for those to emerge from obscurity whose noble qualities are cramped by narrow means at home; but at Rome, for men like these, the attempt is still more hopeless; it is only at an exorbitant price they can get a wretched lodging, keep for their servants, and a frugal meal. A man is ashamed here to dine off pottery ware, which, were he suddenly transported to the Marsi and a Sabine board, contented there with a coarse bowl of blue earthenware, he would no longer deem discreditable. Here, in Rome, the splendor of dress is carried beyond men's means; here, something more than is enough, is taken occasionally from another's chest. In this fault all participate. Here we all live with a poverty that apes our betters. Why should I detain you? Everything at Rome is coupled with high price. What have you to give, that you may occasionally pay your respects to Cossus? that Veiento may give you a passing glance, though without deigning to open his mouth? One shaves the beard, another deposits the hair of a favorite; the house is full of venal cakes.

Juvenal on the Dangers in Rome

“I must live in a place, where there are no fires, no nightly alarms. Already is Ucalegon shouting for water! already is he removing his chattels: the third story in the house you live in is already in a blaze. Yet you are unconscious! For if the alarm begin from the bottom of the stairs, he will be the last to be burnt whom a single tile protects from the rain, where the tame pigeons lay their eggs. Codrus had a bed too small for his Procula, six little jugs the ornament of his sideboard, and a little can besides beneath it, and a Chiron reclining under the same marble; and a chest now grown old in the service contained his Greek books, and mice gnawed poems of divine inspiration. Codrus possessed nothing at all; who denies the fact? and yet all that little nothing that he had, he lost. But the climax that crowns his misery is the fact, that though he is stark naked and begging for a few scraps, no one will lend a hand to help him to bed and board. But, if the great mansion of Asturius has fallen, the matrons appear in weeds, the senators in mourning robes, the praetor adjourns the courts. Then it is we groan for the accidents of the city; then we loathe the very name of fire. The fire is still raging, and already there runs up to him one who offers to present him with marble, and contribute towards the rebuilding. Another will present him with naked statues of Parian marble, another with a chef-d'oeuvre of Euphranor or Polycletus. Some lady will contribute some ancient ornaments of gods taken in our Asiatic victories; another, books and cases and a bust of Minerva; another, a whole bushel of silver. Persicus, the most splendid of childless men, replaces all he has lost by things more numerous and more valuable, and might with reason be suspected of having himself set his own house on fire. [Source: “The Satires of Juvenal, Persius, Sulpicia and Lucilius,” translated by Rev. Lewis Evans (London: Bell & Daldy, 1869), pp. 15-27]

“If you can tear yourself away from the games in the circus, you can buy a capital house at Sora, or Fabrateria, or Frusino, for the price at which you are now hiring your dark hole for one year. There you will have your little garden, a well so shallow as to require no rope and bucket, whence with easy draft you may water your sprouting plants. Live there, enamored of the pitch-fork, and the dresser of your trim garden, from which you could supply a feast to a hundred Pythagoreans. It is something to be able in any spot, in any retreat whatever, to have made oneself proprietor even of a single lizard. Here full many a patient dies from want of sleep; but that exhaustion is produced by the undigested food that loads the fevered stomach. For what lodging-houses allow of sleep? None but the very wealthy can sleep at Rome. Hence is the source of the disease. The passing of wagons in the narrow curves of the streets, and the mutual reviles of the team drivers brought to a standstill, would banish sleep even from Drusus and sea-calves. If duty calls him, the rich man will be borne through the yielding crowd, and pass rapidly over their heads on the shoulders of his tall Liburnian, and, as he goes, will read or write, or even sleep inside his litter, for his sedan with windows closed entices sleep. And still he will arrive before us. In front of us, as we hurry on, a tide of human beings stops the way; the mass that follows behind presses on our loins in dense concourse; one man pokes me with his elbow, another with a hard pole; one knocks a beam against my head, another a ten-gallon cask. My legs are coated thick with mud; then, anon, I am trampled upon by great heels all round me, and the hob-nail of the soldier's caliga remains imprinted on my toe.

“Tunics that have been patched together are torn asunder again. Presently, as the tug approaches, the long fir-tree quivers, other wagons are conveying pine-trees; they totter from their height, and threaten ruin to the crowd. For if that wain, that is transporting blocks of Ligustican stone, is upset, and pours its mountain-load upon the masses below, what is there left of their bodies? Who can find their limbs or bones? Every single carcass of the mob is crushed to minute atoms as impalpable as their souls. While, all this while, the family at home, in happy ignorance of their master's fate, are washing up the dishes, and blowing up the fire with their mouths, and making a clatter with the well-oiled strigils, and arranging the bathing towels with the full oil-flask. Such are the various occupations of the bustling slaves.

“Now revert to other perils of the night distinct from these. What a height it is from the lofty roofs, from which a potsherd tumbles on your brains. How often cracked and chipped earthenware falls from the windows! with what a weight they dint and damage the flint-pavement where they strike it! You may well be accounted remiss and improvident against unforeseen accident, if you go out to supper without having made your will. It is clear that there are just so many chances of death, as there are open windows where the inmates are awake inside, as you pass by. Pray, therefore, and bear about with you this miserable wish, that they may be contented with throwing down only what the broad basins have held. One that is drunk, and quarrelsome in his cups, if he has chanced to give no one a beating, suffers the penalty by loss of sleep; he passes such a night as Achilles bewailing the loss of his friend; lies now on his face, then again on his back. Under other circumstances, he cannot sleep.

“In some persons, sleep is the result of quarrels; but though daring from his years, and flushed with unmixed wine, he cautiously avoids him whom a scarlet cloak, and a very long train of attendants, with plenty of flambeaux and a bronzed candelabrum, warns him to steer clear of. He stands right in front of you, and bids you stand! Obey you must. For what can you do, when he that gives the command is mad with drink, and at the same time stronger than you! "Where do you come from?" he thunders out: "With whose vinegar and beans are you blown out? What cobbler has been feasting on chopped leek or boiled sheep's head with you? Don't you answer? Speak, or be kicked! Say where do you hang out? In what Jew's begging-stand shall I look for you?" Whether you attempt to say a word or retire in silence, is all one; they beat you just the same, and then, in a passion, force you to give bail to answer for the assault. This is a poor man's liberty ! When thrashed he humbly begs, and pummeled with fisticuffs supplicates to be allowed to quit the spot with a few teeth left in his head.

“Nor is this yet all that you have to fear, for there will not be wanting one to rob you, when all the houses are shut up, and all the fastenings of the shops chained, are fixed and silent. Sometimes too a footpad does your business with his knife, whenever the Pontine marshes and the Gallinarian wood are kept safe by an armed guard. Consequently they all flock thence to Rome as to a great preserve. What forge or anvil is not weighed down with chains? The greatest amount of iron used is employed in forging fetters; so that you may well fear that enough may not be left for plowshares, and that mattocks and hoes may run short. Well may you call our great-grandsires happy, and the ages blest in which they lived, which, under kings and tribunes long ago, saw Rome contented with a single jail.

“To these I could subjoin other reasons for leaving Rome, and more numerous than these; but my cattle summon me to be moving, and the sun is getting low. I must go. For long ago the muleteer gave me a hint by shaking his whip. Farewell then, and forget me not! and whenever Rome shall restore you to your native Aquinum, eager to refresh your strength, then you may tear me away too from Cumae to Helvine Ceres, and your patron deity Diana. Then, equipped with my caliga, I will visit your chilly regions, to help you in your satires — unless they scorn my poor assistance.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024