Home | Category: Literature and Drama

DRAMA IN ANCIENT GREECE

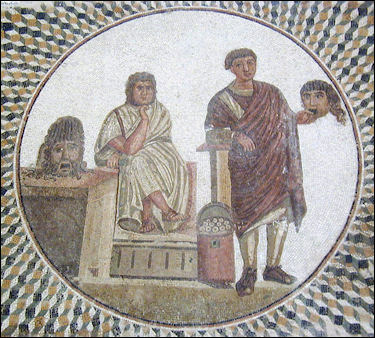

Roman mosaic of Greek drama The Greeks are regarded as the inventors of drama. The Egyptians produced simple plays about the pharaoh’s birth at his crowning and plays about resurrection at the pharaoh’s funeral. The Greeks produced complex dramas, with developed characters, themes and plots that are still present in drama today. With its elaborate masks and costumes and rigidly formalized music, Greek drama has been described as a cross between Japanese Noh theater and grand opera.

Greece tragic-comedy, Chinese opera and Indian Sanskrit Opera are the three oldest dramatic art forms in the world. The word “drama” is derived from Greek words meaning “to do” or “to act.” There have traditionally been two types of plays: 1) tragedies (plays with a tragic ending) and comedies (plays that are funny). Explaining why comedies exist is easy: people like to be entertained and amused. Understanding why tragedies exist is more difficult to grasp. Aristotle explains that at least part of the attraction is the purging effect of releasing emotion while watching a play.

Greek dramas never had more than three actors on stage at one time. Action in the plays was held to a minimum and violence occurred only offstage. Music was supplied by a flutist who led the chorus. The chorus ceremoniously entered and exited at the opening and closing of a play.

RELATED ARTICLES:

THEATERS IN ANCIENT GREECE: STRUCTURES, STAGES, SETS, MACHINES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK THEATER PERFORMANCES: CONTESTS, ACTORS, MASKS, COSTUMES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDIES: PLOTS, TYPES, STRUCTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

GREAT ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY PLAYWRIGHTS: AESCHYLUS, SOPHOCLES AND EURIPIDES europe.factsanddetails.com

ARISTOPHANES AND ANCIENT GREEK COMEDIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org

Origins of Ancient Greek Drama

Ironically, the early forms of the Greek dramatic arts, which puts so many of us to sleep, sprung up out orgiastic Dionysian rites. The first phase of the metamorphosis began in the 7th century B.C. when the frantic dances of the maenads evolved into choral songs called dithyrambs. Dithyrambs were performed by a "circular chorus" of 50 men and boys who sang and danced around an altar in the orchestra area of a theater.

Dionysus and an actor

Tribal choruses competed against one another in festivals sponsored by wealthy citizens. The first prize was a bull and a tripod dedicated to Dionysus, second prize was an amphora of wine, and third prize was a goat. At this point in time music, poetry and drama were essentially the same thing and the subjects of the poem-songs were the Greek myths and episodes from the “ Iliad” and “ Odyssey “. Fertility festivals started dying out around this time because the harvests and rains they promised to deliver failed to arrive. See Wild Dionysian Festivals Above [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Greek theatre had its origins in religious ritual. The god Dionysus, often associated in modern minds only with wine and revelry, was also an agrarian deity, with aspects reminiscent of the Egyptian god, Osiris. Like Osiris, he was twice-born, the second time from the thigh of Zeus, father of gods and men. Celebrations linked to planting and harvesting began in ancient times right on the floor where the grain would be separated from its stalk. It was an opportunity to exhibit the Greek love of dance and music, to give thanks for a bountiful harvest and perhaps to partake of the beverage with which Dionysus is most associated. Some of the nomenclature used in the theatre clearly had its origins on the threshing floor. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

Wild Dionysus Festivals

To pay their respect to Dionysus, the citizens of Athens, and other city-states, held a winter-time festival in which a large phallus was erected and displayed. After competitions were held to see who could empty their jug of wine the quickest, a procession from the sea to the city was held with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and maenads (nymphs), which were often paired together. At the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of iv and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The main purveyors of the Dionysus fertility cult "These drunken devotees of Dionysus," wrote Boorstin, "filled with their god, felt no pain or fatigue, for they possessed the powers of the god himself. And they enjoyed one another to the rhythm of drum and pipe. At the climax of their mad dances the maenads, with their bare hands would tear apart some little animal that they had nourished at their breast. Then, as Euripides observed, they would enjoy 'the banquet of raw flesh.' On some occasions, it was said, they tore apart a tender child as if it were a fawn'"μ

One time the maenads got so involved in what they were doing they had to be rescued from a snow storm in which they were found dancing in clothes frozen solid. On another occasion a government official that forbade the worship of Dionysus was bewitched into dressing up like a maenad and enticed into one of their orgies. When the maenads discovered him, he was torn to pieces until only a severed head remained.μ

See Separate Article: DIONYSUS CULT: MAENADS, MYSTERIES, THEATER AND WILD FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

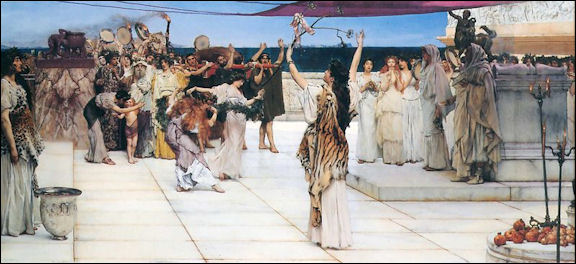

Lawrence Alma-Tadema's Vintage Festival

Dionysian Theater

David Hernández de la Fuente wrote in National Geographic History: In Hellenic culture, Dionysus embodied a symbol of communal cohesion and reconciliation, closely connected with the theater. Every March, the city of Athens would hold a festival known as the Great Dionysia (also called the City Dionysia). Dating as early as the sixth century B.C., this dramatic festival lasted as many as six days. On the first day, a procession would open the festival as a statue of Dionysus was borne to his theater. After the day’s performances, a bull would be sacrificed and a feast held. [Source: David Hernández de la Fuente, National Geographic History, May 25, 2022]

In the days that followed, ancient Greece’s playwrights would present their works — tragedies, comedies, and satyric drama — and compete for top honors. (According to tradition, tragedy was originally related to songs from the Dionysian feast of the tragos, goat, and oidos, song). Actors who gave the best performances would also be awarded prizes. Those taking first place would be given wreaths of ivy, in a nod to the patron god of wine.

The chorus of Euripides’ tragedy The Bacchae, written around 405 B.C., evokes the Dionysian mystery rites: "Blessed is he who, being fortunate and knowing the rites of the gods, keeps his life pure and has his soul initiated into the Bacchic revels, dancing in inspired frenzy over the mountains with holy purifications, and who, revering the mysteries of great mother Kybele, brandishing the thyrsos, garlanded with ivy, serves Dionysus."

Euripides describes the ecstasy that Dionysus unleashes among his retinue: "Go, Bacchae, go, Bacchae . . . sing of Dionysus, beneath the heavy beat of drums, celebrating in delight the god of delight with Phrygian shouts and cries, when the sweet-sounding sacred pipe sounds a sacred playful tune suited to the wanderers, to the mountain, to the mountain!”

Located at the foot of the Acropolis in Athens, the Theater of Dionysus was first erected between the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. After subsequent renovations, it was enlarged to seat as many as 17,000 spectators. Pergamon, an ancient city in Asia Minor that is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, built a massive theater with a capacity for 10,000 spectators. The seating is set into the hillside and faces a temple dedicated to Dionysus, god of the theater.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema's Dedication to Bacchus

Greek Plays at a Dionysian Festival

Greek plays were presented within the context of a Dionysian festival structured along the lines of athletic festivals held at Olympia, Nemea and Delphi, and were of a similar duration. Civic authorities were responsible for organizing the event and it was presided over by the priest of Dionysus. The play itself took place in the open air and, most often, at the base of a sloping hillside which provided each tier of seats with an unimpeded view. In earlier times plain, wooden benches were simply aligned in a semi-circular fashion surrounding the circular orchestra space, at the centre of which stood the altar of Dionysus. In later years, the theatre architecture became much more sophisticated culminating in structures such as the magnificent theatre of Epidaurus, whose acoustics (and those of other Greek theatres) was so much admired. Even a whisper on stage can be clearly heard in the highest row of seats. But it was not in the splendour of these stone theatres however that rapt audiences were first enthralled by the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, These theatres weren’t built until much later.

The Greater Dionysia festival in Athens, took place in March to celebrate the end of winter and the beginning of spring. There were several other festivals of Dionysus throughout the year. During the Athens festival four days of plays were presented, each with no breaks or intermissions. The first day was devoted to comedies submitted by five different playwrights; the next three days to tragedies- with a daily satyr play thrown in for light relief. The winners got prizes- a plain ivy wreath- as well as undisclosed honoraria. |

Seating was on a first-come, first-serve basis, although there was a centre row block of seats reserved for V.I.P’s, including the priests of Dionysus. In the early days admission was free. Later on, there was an admission charge (and some bronze tickets have survived), although that was waived for the poor. There were some large theatres capable of accommodating 15,000 or so spectators but most theatres were considerably smaller than that. Lines were delivered on stage, in the orchestra area, although most action (murders and such) took place off-stage, out of sight of the audience. There were very few props, scenery or backdrops; audiences were expected to use their imagination. |

Development of Ancient Greek Drama

The development of drama took place on two fronts. First was the introduction of an audience. At a Dionysus festival most everyone was a participant in the events. A choral music festival, in contrast, was entertainment, with large numbers of people watching the events and not dancing or singing themselves. The next important step was the introduction of "actors" — people who stepped out of the chorus, bringing the singing to a halt, and acting out a skit.

This dramatic innovation paved the way for Sophocles, Shakespeare, Rogers and Hammerstein, and Steven Spielberg. It enabled the audience too look upon actors and believe, for moments at a time, that they were different individuals than the people they really were, and they were acting out events that could be taking place in a different time. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Some scholars credit the success and influence of Greek drama to “ The Capture of Miletus” , a forgotten play by a forgotten playwright named Phyrnichus that was produced for the Dionysian festival in 492 B.C. The play was about a famous battle between Greeks and Persians lost by the Greeks that took place two year earlier. The play made audiences so depressed that laws were passed forbidding plays based on real life events. With a few exceptions, dramas after that were largely based on a rich supply of myths and famous stories.

Plutarch wrote in “The Life of Solon”, 29 (A.D. 110): “Thespis, at this time [c. 560 B.C.], beginning to act tragedies, and the thing, because it was new, taking very much with the multitude, though it was not yet made a matter of competition, Solon, being by nature fond of hearing and learning something new, and now, in his old age, living idly, and enjoying himself, indeed, with music and with wine, went to see Thespis himself, as the ancient custom was, act: and after the play was done, he addressed him, and asked him if he was not ashamed to tell so many lies before such a number of people; and Thespis replying that it was no harm to say or do so in play, Solon vehemently struck his staff against the ground: "Ah," said he, "if we honor and commend such play as this, we shall find it some day in our business."” [Source: Plutarch, “Plutarch's Lives,” (The "Dryden Plutarch"), (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1910)]

Demosthenes wrote in “Against Midias”, '21.16-18 (c. 360 B.C.): “The sacred apparel — for all apparel provided for use at a festival I regard as being sacred until after it has been used — and the golden crowns, which I ordered for the decoration of the chorus, he plotted to destroy, men of Athens, by a nocturnal raid on the premises of my goldsmith. But not content with this, men of Athens, he actually corrupted the trainer of my chorus; and if Telephanes, the flute-player, had not proved the staunchest friend to me, if he had not seen through the fellow's game and sent him about his business, if he had not felt it his duty to train the chorus and weld them into shape himself, we could not have taken part in the competition, Athenians; the chorus would have come in untrained and we should have been covered with ignominy....he bribed the crowned Archon himself; he banded the choristers against me; he bawled and threatened, standing beside the umpires as they took the oath, he blocked the gangways from the wings.” [Source: Demosthenes, “The Orations of Demosthenes Against Leptines, Midias, Androtion, and Aristocrates,” Charles Rann Kennedy, trans., (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1889)]

Aristotle wrote in “Poetics,” 1449b (340 B.C.): “Indeed it is only quite late in its history that the archon granted a chorus for a comic poet; before that they were volunteers. Comedy had already taken certain forms before there is any mention of those who are called its poets. Who introduced masks or prologues, the number of actors, and so on, is not known. Plot-making originally came from Sicily, and of the Athenian poets Crates was the first to give up the lampooning form and to generalize his dialogue and plots. Epic poetry agreed with tragedy only in so far as it was a metrical representation of heroic action...And then as regards length, tragedy tends to fall within a single revolution of the sun...although originally the practice was the same in tragedy as in epic poetry. Consequently, any one who knows about tragedy, good and bad, knows about epics too, since tragedy has all the elements of epic poetry, though the elements of tragedy are not all present in the epic. Tragedy is, then, a representation of an action that is heroic and complete and of a certain magnitude--by means of language enriched with all kinds of ornament, each used separately in the different parts of the play: it represents men in action and does not use narrative, and through pity and fear it effects relief to these and similar emotions.” [Source: Aristotle, “The Poetics of Aristotle,” 4th Ed., Samuel Henry Butcher, trans., (London: Macmillan, 1917)]

Types of Greek Drama

We must next consider the plays which had to be performed here. On the old Greek stage there were three kinds of drama — tragedies, comedies, and satyric dramas. The comedies were acted singly, and each constituted a complete whole; but tragedy, as it developed out of the Dionysus legend and the division of the action into three connected therewith, was so constructed that a large circle of myth was treated in three separate tragedies, whose contents were connected, but which were structurally complete in themselves, and these were called a Trilogy. But about the same time the curious custom originated of following up these three serious pieces, with their deeply pathetic contents, by a merry satyric drama by the same author, — a wild farce, in which a chorus of satyrs was introduced in connection with some mythical action, which of course, only appeared in travesty; and this combination of four dramas was called a Tetralogy. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Unfortunately no tetralogy has come down complete to us; the trilogy of Aeschylus alone, which deals with the story of Orestes, gives us some notion of the mode in which the tragic poets arranged their material in the form of a trilogy. The first part, “Agamemnon,” represents the murder of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra and Aegisthus; the second, the “Choephorae,” the vengeance taken by Orestes on the murderers; the third, the “Eumenides,” the absolution for the murder of his mother by the Areopagus.

The tragic poets did not very long abide by the custom of presenting complete tetralogies at the Dionysia, in which the trilogy presented one connected subject. It attained its complete development under Aeschylus, but Sophocles already began to depart from it, and in the tetralogies with which he and Euripides competed, the internal connection between the tragedies was wanting. In later times it was customary for tragedies complete in themselves to be acted singly, so that the poets competed with drama against drama; still, the inscriptions show us that even in the fourth century tetralogies were acted, though they may not have been connected. Each of these three kinds of drama underwent several changes during the course of Greek literature.

Politics and Drama in Ancient Greece

Mary Beard wrote in the New Statesman, “In ancient Athens, politics and theatre went hand in hand. Art, literature and drama blended easily with Athenian imperialism and with the version of "democracy" that underpinned it. Sophocles - the 5th-century BC playwright whose tragedy Oedipus the King was part of the inspiration for Freud's "Oedipus complex" - is a nice example of how the blend worked.[Source: Mary Beard, New Statesman, October 14, 2010]

Mary Beard wrote in the New Statesman, “In ancient Athens, politics and theatre went hand in hand. Art, literature and drama blended easily with Athenian imperialism and with the version of "democracy" that underpinned it. Sophocles - the 5th-century BC playwright whose tragedy Oedipus the King was part of the inspiration for Freud's "Oedipus complex" - is a nice example of how the blend worked.[Source: Mary Beard, New Statesman, October 14, 2010]

In 440BC, a few months after his Antigone won first prize at the Athenian drama festival, Sophocles served as one of the commanding officers of an Athenian task force that sailed off to put down a rebellion on the island of Samos. The inhabitants had decided to break away from Athens's empire - the network of Athenian satellite states spread all over the eastern Mediterranean - and they had to be brought back into the fold. The irony was that a few decades earlier, Athens had led Greece to victory against a vast Persian invasion; now, the Athenians had imposed their own tight control over their former allies (which may have left some wondering whether conquest by the Persians might have been the better option). More equal than others

The people of Samos got off lightly. They were brought back by force into "alliance" (as the euphemism was) with Athens but there was no mass enslavement, no massacre of the male population, no occupying garrison permanently stationed there, no confiscation of land, such as we find elsewhere in the Athenian orbit. The penalty paid by the Samians was modest - an imposed democracy, the removal of the island's independent naval deterrent and vast sums to pay in financial compensation over years to come.

All the same, it is hard to think that one month Sophocles was putting the finishing touches to his great Antigone - a play about ethical conflicts between the individual conscience and the dictates of the state - and the next month he was sailing off to force the Samians to toe the Athenian line once again. Yet, oddly, at the time, there was a common story that he was elected to his military command because of the popular success of Antigone, that celebration of individual liberty. Stage of empire

Or maybe it is not so odd. True, the great tragedies that were acted on the Athenian stage debated all kinds of moral and ethical issues, from incest and matricide to the workings of the divine will. But the festival at which those plays were first performed was one of the most jingoistic moments of Athenian culture - and became increasingly so over the second half of the 5th century, during the period of Sophocles's lifetime. The plays may have debated the rights and wrongs of the exercise of power, but the rituals that went on just before the performances showed no hesitation whatsoever about Athenian control in the world. The most dramatic of these was the presentation of the tribute in cash from Athens's subject states to the Athenian authorities - deposited, it seems, directly on to the theatre stage. This spectacle, however, was followed by a parade that would have fitted easily into the public ceremonials of Soviet Russia: war orphans, those whose fathers had died fighting for the Athenian empire, were trooped across the stage.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024