Home | Category: Literature and Drama

ANCIENT GREEK COMEDIES

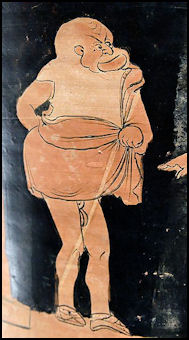

actor as donkey, 5th century BC While tragedies told tales of unapproachable gods and noble heroes, comedies made fun of people from everyday life. Aristotle called comedy an "imitation of men worse than average...that excite laughter...without causing pain."

In the comedies chorus members sometimes dressed like clouds or wasps. The chorus generally did not interact with the actors but they sometimes taunted them, made lewd gestures directed at them and made jokes at their expense. Satyr plays burlesqued well known legends and often depicted major characters in gross and obscene manner. The chorus members were dressed like satyrs and responded to the orders of their fat drunken leader, Silenus. Comic playwrights had the most fun on the Day of Misrule, a holiday when nothing was sacred. Arcane philosophers were satirized, sexual morality was mocked, and even the gods were objects of ridicule.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Unlike the Greek tragedy, the comic performances produced in Athens during the fifth century B.C., the so-called Old Comedy, ridiculed mythology and prominent members of Athenian society. There seems to have been no limit to speech or action in the comic exploitation of sex and other bodily functions. Terracotta figurines and vase paintings dated around and after the time of Aristophanes (?460/50–ca. 387 B.C.) show comic actors wearing grotesque masks and tights with padding on the rump and belly, as well as a leather phallus. [Source: Colette Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DRAMA IN ANCIENT GREECE: ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, TYPES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THEATERS IN ANCIENT GREECE: STRUCTURES, STAGES, SETS, MACHINES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK THEATER PERFORMANCES: CONTESTS, ACTORS, MASKS, COSTUMES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDIES: PLOTS, TYPES, STRUCTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

GREAT ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY PLAYWRIGHTS: AESCHYLUS, SOPHOCLES AND EURIPIDES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Classical Comedy” by Aristophanes, Menander, et al. (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Comedies” (Penguin Classics) by Terence and Betty Radice (1976) Amazon.com;

“Aristophanic Comedy” by K. J. J. Dover (1972) Amazon.com;

“The Greek and Roman Stage” by David Taylor (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greek Theater” by Mary Louise Hart (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theater” by Graham Ley Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre” by Marianne McDonald and Michael Walton (2011) Amazon.com;

“Theater of the People: Spectators and Society in Ancient Athens”

by David Kawalko Roselli (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies” (Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents) by Peter Wilson (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama (Blackwell) by Ian C. Storey and Arlene Allan (2013) Amazon.com;

“Guide To Greek Theatre And Drama (Plays and Playwrights)” by Kenneth McLeish and Trevor R. Griffiths (2003) Amazon.com;

“Theatre in Ancient Greek Society” by J. R. Green (1996) Amazon.com;

“Looking at Greek Drama: Origins, Contexts and Afterlives of Ancient Plays and Playwrights” by David Stuttard (2024) Amazon.com;

“Nothing to Do with Dionysos? Athenian Drama in Its Social Context” by John J. Winkler and Froma I. Zeitlin (1990) Amazon.com;

“Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy” by Simon Goldhill and Robin Osborne (1999) Amazon.com;

Aristophanes: “Lysistrata and Other Plays” (Penguin Classics) by Aristophanes Amazon.com;

“Aristophanes: Frogs and Other Plays” by Aristophanes and Stephen Halliwell (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Birds and Other Plays” (Penguin Classics) by Aristophanes, David Barrett, et al. (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Clouds” by Aristophanes Amazon.com;

Appreciating Ancient Greek Comedy

Greek comedy is often difficult for us to fully appreciate based as it was on local events and incidents familiar primarily to the community. References that might have had Athenians rolling in the aisles leave most of us with a quizzical look. The stereotypes though are known to us- the crafty slave, the greedy entrepreneur, the lusty sailor, etc. Aristophanes, author of The Birds, The Frogs and The Clouds was from the Old Comedy Period (c.450 B.C.) and the titles of his plays reflect costumes that would have been worn by the chorus. No one escaped the acerbic wit of Aristophanes, especially politicians and philosophers, and there is little doubt that in modern times he would be charged with slander and libel. Even in those liberal times he did not always escape unscathed; his attacks on Athens while it was at war with Sparta provoked considerable anger. [Source: Canadian Museum of History]

In the second half of the fourth century B.C., the so-called New Comedy of Menander (?344/43–292/91 B.C.) and his contemporaries gave fresh interpretations to familiar material. Menander is the only representative of the New Comedy Period (c. 350 B.C.) with any surviving works to his credit. He can be considered as one of the major founders of modern comedy. He wrote more than 100 plays but only one complete play survives. In many ways comedy became simpler and tamer, with very little obscenity. The grotesque padding and phallus of Old Comedy were abandoned in favor of more naturalistic costumes that reflected the playwrights' new style. Subtle differentiation of masks worn by the actors paralleled the finer delineation of character in the texts of New Comedy, which dealt with private and family life, social tensions, and the triumph of love in a variety of contexts.

Aristotle (384-323 B.C.) wrote in “The Poetics”: “ In Comedy this is already apparent: for here the poet first constructs the plot on the lines of probability, and then inserts characteristic names- unlike the lampooners who write about particular individuals. But tragedians still keep to real names, the reason being that what is possible is credible: what has not happened we do not at once feel sure to be possible; but what has happened is manifestly possible: otherwise it would not have happened. Still there are even some tragedies in which there are only one or two well-known names, the rest being fictitious. In others, none are well known- as in Agathon's Antheus, where incidents and names alike are fictitious, and yet they give none the less pleasure. We must not, therefore, at all costs keep to the received legends, which are the usual subjects of Tragedy. Indeed, it would be absurd to attempt it; for even subjects that are known are known only to a few, and yet give pleasure to all. It clearly follows that the poet or 'maker' should be the maker of plots rather than of verses; since he is a poet because he imitates, and what he imitates are actions. And even if he chances to take a historical subject, he is none the less a poet; for there is no reason why some events that have actually happened should not conform to the law of the probable and possible, and in virtue of that quality in them he is their poet or maker.”

Elements of Ancient Greek Comedy

actor

The older comedy, of which Aristophanes is the chief representative, made use of chorus and dialogue in the same way as tragedy. Its subjects referred to actual life, and dealt with political, social, and literary questions, and others of universal interest, but in a fantastic manner, with the most eccentric masques and absurd contrivances, dealing out hits all round with the wildest licence, and sparing neither the common citizen nor the most powerful and exalted personages. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The part played by the chorus differed in many respects from that undertaken in tragedy; the comic chorus very often stepped entirely outside the action, and, as the mouthpiece of the poet, who used this opportunity to bring his political or other opinions before the public, to fight out personal quarrels, and, in general, to say whatever he pleased, it directed itself to the public; such are those comic choruses which bear the name Parabasis. The comic chorus was also adequately distinguished from the tragic, both in the difference of costume and in the number of its members; the latter were generally only twelve, and the former twice as many. Again, the dances and rhythmic movements of the comic choruses differed greatly from those of the tragic.

But even during the lifetime of Aristophanes, the transformation of the comedy began in its outer form as well as in its real nature. The outer change consisted in the abolition of the chorus, the expenditure of which the citizens were no longer willing to defray, and thus an excellent opportunity was lost of saying rough truths with a laughing face, and the way was paved for a gradual change of subject. The change was accomplished by the so-called newer Attic Comedy, which had no chorus, and, instead of political or social satire, took as its subject pictures from Athenian life, love intrigues, comic misunderstandings, etc., and, in fact, more closely resembled our modern comedies. Then the lyric element naturally vanished, which in the older comedy, as in tragedy, appeared not only in the chorus but also in the dramatic performance of the actors; the action was presented only by dialogue, and the musical element, which had formerly played a very important part in comedy, was confined to accompaniment of the recitation, and thus became entirely subordinate.

Ancient Greek Satire

The satyric drama is the one in which we can trace the fewest changes, but it had only a short existence. It was invented by Pratinas, a contemporary of Aeschylus, probably with the intention of compensating the public, who must have sadly missed the popular sports which had formerly enlivened the celebration of the Dionysia, and to satisfy their desire for coarser fare. At first the satyric drama seems to have preceded the tragedies, but this was soon changed. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

In the best period of the drama we never find satyric plays alone without tragedies preceding them; they were so essentially a part of the tragedy that we only hear of tragic writers as composers of satyric dramas. The best period of the satyric drama was the time of Pratinas and Aeschylus; Sophocles and Euripides, too, composed them — one by the latter has come down to us, the “Cyclops” — but at that time its best period was already over, since it no longer formed the necessary conclusion of a dramatic tetralogy.

Still, satyric dramas retained their position on the stage until the second century, and, in fact, the Alexandrine poets made a fresh attempt to connect the satyric drama with tragedies in a tetralogy. We know very little about the subject of these later satyric dramas. The titles of Alexandrine plays that have come down to us show that at that time actual life was introduced, though the mythological subjects which had formed the sole basis of the ancient satyric drama were also used.

Costumes in Ancient Greek Comedies

We give here several examples of pictures from ancient comedy. In one image the stage has on its left side a scaffolding covered in with a roof, to which a staircase leads; on the floor of this erection lie a bundle of beds or carpets, a cap, and a litter. Chiron, whose name appears on the plate, is climbing up the staircase with difficulty, and bending down leaning on his rough knotty stick; a slave is pushing him up from behind, while Xanthias, standing on the top of the stairs, seizes hold of his head as though to draw him up. In the background we see two not specially attractive nymphs, of whom only the upper part is visible; these again are designated in the inscription; the youth on the right, in the himation, and without a mask, is not one of the actors. Possibly this is a representation of the sick Chiron seeking healing at a sanctuary of the nymphs. The costume and the tricots, as well as the grotesque masks, are worthy of notice.

One vase painting has not been satisfactorily explained. It is evident that Hercules is engaged in some love adventure, as is proved by the lion’s skin in which the actor, who is jesting with a girl, is dressed, and the club which rests beside him. The figure on the right probably represents an old woman; on the left is a man contemplating the scene. With the exception of the girl and the woman in the middle, the masks are extreme caricatures.

A Pompeian wall-painting, may be here compared, because it evidently imitates Greek prototypes, and the scene represented in the center belongs to the later comedy. The one actor with a curious head-dress and a spear seems to be a sort of Miles Gloriosus, the man in a reverential position speaking to him a parasite. The three youths who stand near wear no masks, and it is therefore doubtful whether they are to be regarded as part of the representation in the character, perhaps, of statists, who may have appeared without masks. Two old men to the right and left of the central scene, seated on a somewhat lower plane, and leaning on their knotty sticks, with serious official mien, are doubtless theatrical police, who had to keep order during the performance. It is not easy to say what place in the theatre they were supposed to occupy.

Aristophanes

We gain some information concerning the costume of the satyric drama from a very interesting vase painting, which cannot, however, for various reasons, be represented here, and which we propose, therefore, shortly to describe. This represents the personages taking part in a satyric drama before the commencement of the performance; a group in the center of the top row does not belong to the performers: this represents Dionysus resting on a couch with Ariadne, near him is a woman holding up a mask, probably a Muse, and the little Eros Himeros. To the right and left of this group, which must be regarded as the ideal scene, stand three actors, each holding his mask in his hand (the strings by which they were held are visible); next on the right is Hercules, who may be recognised by his lion’s skin, club, and quiver; near him is the “Papposilenus,” his whole body covered with skin, a panther’s skin thrown over his left arm, and holding a short staff; we do not know the name of the third actor on the left. The chorus of satyrs consists of eleven persons, of whom only one has as yet put on his mask. That one is practising a dance in preparation for the performance.

Most of the chorus are dressed alike with only a little covering of skin round their loins, and the short satyr’s tail; one of them, however, has a little garment of some material with a pattern, and another wears an embroidered dress with himation; he might be taken for an actor if his mask did not bear the satyric type like the rest, the pug nose and the pointed ears. In the middle of the lowest row two musicians are represented: a splendidly dressed flute player seated, in front of him stands a cithara player. Further to the left sits a young man holding a roll in his hand, another roll lies on the ground, a lyre is visible behind him. In spite of his striking youthfulness, this young man is probably the teacher of the chorus or the poet himself. The actors are bearded men, the chorus beardless youths. Two tripods close by probably suggest the prize to be competed for.

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (c.445-c.385 B.C.) was the greatest comic playwrights, writing in a rough style later known as "old comedy". He wrote 54 comedies, of which only 11 survived. They including “The Acharnians” (425 B.C.); “The Birds” 414 B.C.); “The Clouds” (423 B.C.), which pokes fun at Socrates; The Ecclesiazusae (Women in Politics); “The Frogs” (405 B.C.); “The Knights” (424 B.C.); Lysistrata 411 B.C.), about a sex strike; and Plutus (408 B.C.), his last play.

The comic plays of Aristophanes (450-357 B.C.) are the only Greek comedies that have survived. For the most part they featured stereotyped characters we are familiar with today: hen-pecked husbands, nagging wives, boastful soldiers and vain and conniving seductresses. Aristophanes often wrote about issues that affected ordinary Greeks — war, women rights, low pay and sex. He could be viciously sarcastic but often stood up for the rights of the poor.

On the Day of Misrule, Aristophanes went as far as belittling Cleon the Terrible while he was still alive. This ruler was known as "the most violent man in Athens" with a "frown that made people vomit with fear." In one play Cleon was portrayed as a slave who brought trouble to his household. As a punishment he was forced to sell donkey sausages and dog meat on the streets while prostitutes hurled insults and dirty bath water at him. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Aristophanes hold the record for longest word ever used in the history of literature — Lopadotemach- oseelachogaleokranioleipsanodrimhypotrimmatosilphioparaomelitokatakenchymenokichlepikossyphophat- toperisteralektryonoptekephalliokigklopeleiolagoiosiraiobaphetraganopterygon. The word appeared in the comedy “Eccalziazusae” and had 182 letters. It meant a dish made with 17 sweet and sour ingredients, including brains, mullet, vinegar, bone marrow, honey, pickled vegetables and ouzo. [Source: People’s Almanac]

Plays by Aristophanes

comedic slave actor WEB MIT Classics Archive: Aristophanes classics.mit.edu

See 2ND Old Comedy Study Guide” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Acharnians” (425 B.C.) “ Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Acharnians” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Birds” (414 B.C.) Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Birds” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Clouds” (423 B.C.) “ Internet Archive Web.archive.org . Pokes fun at Socrates.

See 2ND Study Guide” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Clouds” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Ecclesiazusae” (Women in Politics) Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Frogs” (405 B.C.) Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Frogs” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Knights” 424 B.C.) “ Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Knights” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Lysistrata” 411 B.C.) “ Internet Archive Web.archive.org , about a sex strike.

See 2ND Study Guide” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Lysistrata” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Peace” (421 B.C.) “ Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Peace” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Plutus” (382 B.C.) (his last play) “ Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Thesmophorizusae” (411 B.C.) “Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Wasps” 422 B.C.) Internet Archive Web.archive.org

Aristophanes’s Satire, Women and Sex

Aristophanes plays often poked fun of his contemporaries. His most successful play, both then and now — “Frogs” — ridiculed Sophocles and Euripides, only a year after they died, with characters dressed in frog costumes. “The Wasps” satirized the Athenian legal system by portraying juries and lawyers as raking in money by prolonging trials. “The Clouds” ridiculed the Sophists for practicing "Thinkery," a philosophy in which the "Worse Cause appeared the Better." Once he was denied a drama prize for making too much fun of Solon. Aristophanes’s other plays are “Birds” , “Knights” , “Lysieria” and “Ecclesiazususae” .

The comedy “Lysistrata” features a heroine who tries to bring the war to an end by leading a sex strike. There is reason to believe that Lysistrata herself is drawn in part from a contemporary historical figure, Lysimache, the priestess of Athena Polias on the Acropolis.

Homosexuality popped in some of his plays. Relationships between older men and teenage boys was believed to be common. In “ Clouds” Aristophanes wrote: "How to be modest, sitting so as not to expose his crotch, smoothing out the sand when he arose so that the impress of his buttocks would not be visible, and how to be strong...The emphasis was on beauty...A beautiful boy is a good boy. Education is bound up with male love, an idea that is part of the pro-Spartan ideology of Athens...A youth who is inspired by his love of an older male will attempt to emulate him, the heart of educational experience. The older male in his desire of the beauty of the youth will do whatever he can improve it."

In Aristophanes's “ The Birds” , one older man says to another with disgust: "Well, this is a fine state of affairs, you demanded desperado! You meet my son just as he comes out of the gymnasium, all rise from the bath, and don't kiss him, you don't say a word to him, you don't hug him, you don't feel his balls! And you're supposed to be a friend of ours!"

Aristophanes’ Depiction of Socrates in the Clouds

Socrates in a basket

According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Aristophanes’ play “”The Clouds” depicts the tribulations of Strepsiades, an elderly Athenian citizen with significant debts. Deciding that the best way to discharge his debts is to defeat his creditors in court, he attends The Thinkery, an institute of higher education headed up by the sophist Socrates. When he fails to learn the art of speaking in The Thinkery, Strepsiades persuades his initially reluctant son, Pheidippides, to accompany him. Here they encounter two associates of Socrates, the Stronger and the Weaker Arguments, who represent lives of justice and self-discipline and injustice and self-indulgence respectively.

On the basis of a popular vote, the Weaker Argument prevails and leads Pheidippides into The Thinkery for an education in how to make the weaker argument defeat the stronger. Strepsiades later revisits The Thinkery and finds that Socrates has turned his son into a pale and useless intellectual. When Pheidippides graduates, he subsequently prevails not only over Strepsiades’ creditors, but also beats his father and offers a persuasive rhetorical justification for the act. As Pheidippides prepares to beat his mother, Strepsiades’ indignation motivates him to lead a violent mob attack on The Thinkery. [Source: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP) ]

“Aristophanes’ depiction of Socrates the sophist is revealing on at least three levels. In the first instance, it demonstrates that the distinction between Socrates and his sophistic counterparts was far from clear to their contemporaries. Although Socrates did not charge fees and frequently asserted that all he knew was that he was ignorant of most matters, his association with the sophists reflects both the indeterminacy of the term sophist and the difficulty, at least for the everyday Athenian citizen, of distinguishing his methods from theirs. Secondly, Aristophanes’ depiction suggests that the sophistic education reflected a decline from the heroic Athens of earlier generations. Thirdly, the attribution to the sophists of intellectual deviousness and moral dubiousness predates Plato and Aristotle.”

Socrates Dialogue from the Clouds

Aristophanes wrote in “The Clouds”:

Strepsiades: Who is this man suspended up in a basket?

Disciple: That's himself.

Strepsiades: Who's himself?

Disciple: Socrates.

Strepsiades: Socrates! Oh! I pray you, call him right loudly for me.

Disciple: Call him yourself; I have no time to waste. (He departs. The machine swings in Socrates in a basket.)

Strepsiades: Socrates! my little Socrates!

Socrates (loftily): Mortal, what do you want with me?

Strepsiades: First, what are you doing up there? Tell me, I beseech you.

Socrates (pompously): I am traversing the air and contemplating the sun.

Strepsiades: Thus it's not on the solid ground, but from the height of this basket, that you slight the gods, if indeed....

Socrates: I have to suspend my brain and mingle the subtle essence of my mind with this air, which is of the like nature, in order clearly to penetrate the things of heaven. I should have discovered nothing, had I remained on the ground to consider from below the things that are above; for the earth by its force attracts the sap of the mind to itself. It's just the same with the watercress.

Strepsiades: What? Does the mind attract the sap of the watercress? Ah! my dear little Socrates, come down to me! I have come to ask you for lessons.

Socrates (descending): And for what lessons?

Strepsiades: I want to learn how to speak. I have borrowed money, and my merciless creditors do not leave me a moment's peace; all my goods are at stake.

Socrates: And how was it you did not see that you were getting so much into debt?

Strepsiades: My ruin has been the madness for horses, a most rapacious evil; but teach me one of your two methods of reasoning, the one whose object is not to repay anything, and, may the gods bear witness, that I am ready to pay any fee you may name.

Socrates: By which gods will you swear? To begin with, the gods are not a coin current with us.

Strepsiades: But what do you swear by then? By the iron money of Byzantium?

Socrates: Do you really wish to know the truth of celestial matters?

Strepsiades: Why, yes, if it's possible.

Socrates: ....and to converse with the clouds, who are our genii?

Strepsiades: Without a doubt.

Socrates: Then be seated on this sacred couch.

Strepsiades (sitting down): I am seated.

Socrates: Now take this chaplet.

Strepsiades: Why a chaplet? Alas! Socrates, would you sacrifice me, like Athamas?

Socrates: No, these are the rites of initiation.

Strepsiades: And what is it I am to gain?

Socrates (pouring flour on Strepsiades): You will become a thorough rattle-pate, a hardened old stager, the fine flour of the talkers....But come, keep quiet.

Strepsiades: By Zeus! That's no lie! Soon I shall be nothing but wheat-flour, if you powder me in that fashion.

Socrates: Silence, old man, give heed to the prayers. (In an hierophantic tone) Oh! most mighty king, the boundless air, that keepest the earth suspended in space, thou bright Aether and ye venerable goddesses, the Clouds, who carry in your loins the thunder and the lightning, arise, ye sovereign powers and manifest yourselves in the celestial spheres to the eyes of your sage.

Strepsiades: Not yet! Wait a bit, till I fold my mantle double, so as not to get wet. And to think that I did not even bring my traveling cap! What a misfortune!

Socrates (ignoring this)

“Come, oh! Clouds, whom I adore, come and show yourselves to this man, whether you be resting on the sacred summits of Olympus, crowned with hoar-frost, or tarrying in the gardens of Ocean, your father, forming sacred choruses with the Nymphs; whether you be gathering the waves of the Nile in golden vases or dwelling in the Maeotic marsh or on the snowy rocks of Mimas, hearken to my prayer and accept my offering. May these sacrifices be pleasing to you.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024