Home | Category: Religion / Religion and Gods

DIONYSUS CULT

Because his half-breed status made his position at Olympus tenuous, Dionysus did everything he could to make his mortal brethren happy. He gave them rain, male semen, the sap of plants and "the lubricant and stimulant of dance and song" — wine.

Because his half-breed status made his position at Olympus tenuous, Dionysus did everything he could to make his mortal brethren happy. He gave them rain, male semen, the sap of plants and "the lubricant and stimulant of dance and song" — wine.

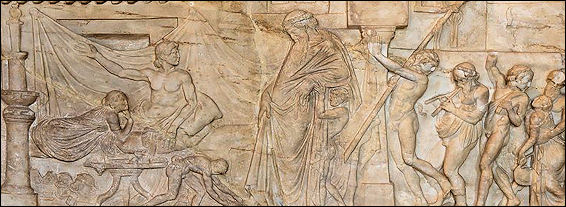

David Hernández de la Fuente wrote in National Geographic History: Worship of Dionysus was not uniform in the classic world. Some of it was public and organized, while other rituals were mysterious and carried out in secret. Many Greeks showed their reverence for Dionysus through festivals; in Rome, where he was called Bacchus, these became the Bacchanalia — wild rituals celebrated at night in forests and mountains. The maenads would enter a delirious state of ecstasy, then — inspired by the personification of Dionysus in the form of a priest — dance wildly before setting out on a hunt. [Source: David Hernández de la Fuente, National Geographic History, May 25, 2022]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Dionysus: Myth and Cult” by Walter F. Otto (1995) Amazon.com;

“God Who Comes, Dionysian Mysteries Reclaimed: Ancient Rituals, Cultural Conflicts, and Their Impact on Modern Religious Practices” (2003) by Rosemarie Taylor-Perry Amazon.com;

“The Greeks and the Irrational” by E. R. Dodds (1951) Amazon.com;

“Dionysos: Exciter to Frenzy: a Study of the God Dionysos: History, Myth and Lore” by Vikki Bramshaw Amazon.com;

“The Bacchae and Other Plays (Penguin Classics) by Euripides Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Cults: A Guide” by Jennifer Larson Amazon.com;

“The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece” by Marguerite Mary Rigoglioso (2011) Amazon.com;

“Greek Heroine Cults” by Jennifer Larson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore” by Jennifer Larson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece” by Philippe Borgeaud (1988) Amazon.com;

“Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (2023) Amazon.com;

“Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus” by Dignas (2008) Amazon.com;

“Savage Energies: Lessons of Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece” by Walter Burkert (2001) Amazon.com;

“Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion” by Matthew Dillon (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Miasma: Pollution and Purification in Early Greek Religion” by Robert Parker (1983) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greek Religion” by Daniel Ogden (2007) Amazon.com;

“A History of Greek Religion” by Martin P. Nilsson (1925) Amazon.com;

Dionysus

Dionysus (Bacchus to Romans) was the god of drama, dance, music, fertility and wine. He was the only god to be born twice and the only one with a mortal parent. Because of his association with drinking, partying, festivals and having a good time it is not surprising that he was one of the most popular gods. Dionysus often traveled is disguise. He was known for appearing and reappearing quickly. When he wanted to make a show he arrived with a procession of nymphs and satyrs.

Marianne Bonz wrote for PBS’s Frontline: “Although not one of the original Olympians, the cult of Dionysus was very old and was celebrated throughout the Greek world and beyond. As the god of the vine and of the pleasures of its cultivation, his cult became associated with that of Demeter at an early time. As with Demeter, his devotees ranged the entire spectrum of the social scale. Likewise, his cultic observance ranged from dignified ceremonies and parades to orgiastic celebrations and festivals. [Source: Marianne Bonz, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Later Rome, fearing that these festivals would lead to civil unrest, attempted to suppress his cult, but it met with very little success. Although the Romans could not curtail the immense popularity of Dionysus, the god's appearance and the legends surrounding his worship did change dramatically over time.

“Even though fairly early in his history Dionysus's appearance changed from that of a mature, bearded man of a decidedly rustic quality to a long-haired and somewhat effeminate adolescent with exotic attributes, throughout most of his history his essential character remained that of a charming rogue. He was depicted as the god who brought the joys and ecstasies of the vine, as well as the fruits of civilization, and not only to Greece but also to far-away India and Egypt. But Dionysus also could reduce even people of consequence to madness, if they crossed him.

See Separate Article: DIONYSUS europe.factsanddetails.com

Dionysos Mystery Cults

Dionysus by Caravaggio David Hernández de la Fuente wrote in National Geographic History: Dionysus was also worshipped through a series of secret rituals known today as the Dionysian Mysteries. These are thought to have evolved from an unknown cult that spread throughout the Mediterranean region alongside the dissemination of wine (though it’s possible that mead was the original sacrament).[Source: David Hernández de la Fuente, National Geographic History, May 25, 2022]

As the patron of the Dionysian Mysteries — secret rites to which only initiates were admitted, such as those performed in honor of Demeter, goddess of agriculture, and later, of Isis (originally from Egypt) and Mithras (originally from Iran) — Dionysus was a disruptive deity, entering civilization and throwing out the established order. When he arrived, liberation and transgression had their turn.

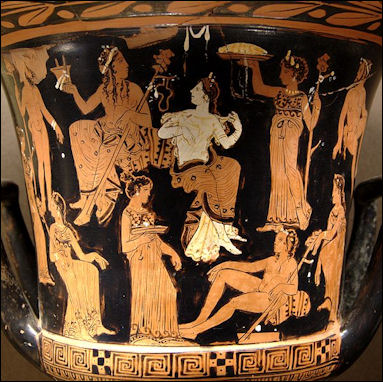

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “While at Eleusis and other sanctuary-based cults participation in the mysteries was a single transformative event, the initiates of the Bacchic mysteries met repeatedly. Bacchus was an epithet of the god Dionysos, possibly referring to the namesake branch carried by his initiates, who also wore headbands tied into a bow. In myth, Dionysos is followed by his thiasos, a retinue of satyrs and maenads who wear fawn skins, are crowned by wreaths of ivy or oak, and hold thyrsoi: giant fennel stalks covered with ivy and topped by pine cones, often wound with fillets. Bacchic thiasoi existed from at least the fifth century B.C. onward. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/] \^/

Practices of the Dionysos Mystery Cults

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: Dionysos Mystery Cults “were small voluntary organizations of worshippers, sponsored in Roman times by wealthy patrons. Secret activities, called teletai or orgia, took place in the mountains, where the Bacchoi engaged in ecstatic dancing, singing, revelry, and even eating raw meat (homophagia). The wine-induced Bacchic frenzy was seen as a temporary madness that transported them from civilization to wilderness, both literally and metaphorically [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/] \^/

“The followers of Dionysos derived many of their eschatological beliefs and ritual prescriptions from Orphic literature, a corpus of theogonic poems and hymns. The mythical Thracian poet Orpheus, the archetypical musician, theologian, and mystagogue, was credited with the introduction of the mysteries into the Greek world. According to myth, Orpheus' reclusion that followed his unsuccessful attempt to bring back his wife Eurydice from the Underworld or, alternatively, his invention of homosexuality brought about the tragic, violent death he suffered at the hands of Thracian women. \^/

“References by Herodotus and Euripides attest to the existence of certain Bacchic-Orphic beliefs and practices: itinerant religion specialists and purveyors of secret knowledge, called Orpheotelestai, performed the teletai, private rites for the remission of sins. For the Orphics, Dionysos was a savior god with redeeming qualities. He was the son of Zeus and Persephone and successor to his throne. When the Titans attacked and dismembered the baby Dionysos, Zeus in retaliation blazed the perpetrators with his thunderbolt. From the Titans' ashes the human race was born, burdened by the horrific inheritance of an "original sin." Similarly to the Pythagoreans, the Orphics did not consume meat and were not to be buried in woolen garments. Archaeological finds from southern Italy, northern Greece, the Pontic area, and Crete provide important evidence for the Bacchic-Orphic mysteries: to ensure personal salvation and eternal bliss in the afterlife, objects such as the famed Derveni papyrus, inscribed bone plaques and gold leaves (lamellae), or gilded mouth-pieces were buried with the initiates.” \^/

Dionysian Festivals

dancing maenad In return for all Dionysus provided, the Greeks held winter-time festivals in Athens in which large phalluses were erected and displayed, and competitions were held to see which Greek could chug his or her jug of wine the quickest. Processions with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and nymphs were staged, and at the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

The text believed to be from funeral of an Dionysus cult initiate read: “I am a son of Earth and Starry Sky; but I am desiccated with thirst and am perishing, therefore give me quickly cool water flowing from the lake of recollection.” The “long, cared way which also other...Dionysus followers gloriously walk” is “the holy meadow, for which the initiate is not liable for penalty” or “shall be a god instead of a mortal.”

Annual Dionysiac festivals included the night celebrations in some parts of Greece, but especially on the Cithaeron and Parnassus, on the Islands, and in Asia Minor in which only women, both married and unmarried, took part. The wild and orgiastic character of these Dionysia originated in Thrace, but spread very quickly, and found much favor among the women, who were inclined to this kind of ecstatic worship. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

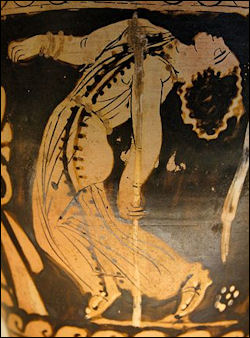

These festivals fell in the middle of winter, about the time of the shortest day; the women dressed for the purpose in Bacchic costume, threw deer-skins over their shoulders, let their hair fly loose, and took in their hands the thyrsus staff and tambourine, and thus wandered to the hills near their homes, and there performed all manner of mysterious ceremonies, sacrifices, dances, etc., amid the wildest merriment resulting from the juice of the grape, which was seldom allowed them. We can form some notion of the wild nature of the proceedings from the descriptions of the poets and artistic representations of Maenads; still, we must always remember that both poets and artists described not so much the customs of their own day as those of mythical or heroic periods, and permitted themselves many exaggerations which did not correspond to reality.

Lucian De Salt wrote (c. A.D. 160): “The Bacchic dance is taken especially seriously in Ionia and Pontus, although it belongs to Satyric drama, and has so taken hold of people there that, in the festival time, they put aside everything else and sit the day through, watching corybants, satyrs, and shepherds; and people of the best lineage and foremost in every city dance, not in the least embarrassed but proud of it.....Each town or region celebrates the festivals of the gods with its own rites; thus, to Egyptian deities generally by lament, to the Hellenic for the most part by choruses, but to the non-Hellenic by the clangor of cymbalists, drummers, and flutists....At Delos not even the sacrifices are offered without dancing. Boy choruses assembled and, to the pipe and kithara, some moved about, singing, while the best performed a dance in accompaniment; and hymns written for such choirs are called dances-for-accompaniment."

In a letter to Aureleus Theon, expressing the business side of the festival, Aurelius Asclepiades wrote (c. A.D. 295): “I desire to hire from you Tisaïs, the dancing girl, and another, to dance for us at our festival of Bacchias, for fifteen days from the 13th Phaophi by the old calendar. You shall receive as pay 36 drachmai a day, and for the whole period 3 artabai of wheat, and 15 loaves; also, three donkeys to fetch them and take them back.”

Maenads at Wild Dionysus Festivals

Maenad with a thyrsus and a leopard and a snake rolled up over her head; from kylix dated to 490–480 BC

Maenads were often present at the Dionysus Festivals. They were often paired together. Some translate maenads as nymphs. The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of iv and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The main purveyors of the Dionysus fertility cult "These drunken devotees of Dionysus," wrote Boorstin, "filled with their god, felt no pain or fatigue, for they possessed the powers of the god himself. And they enjoyed one another to the rhythm of drum and pipe. At the climax of their mad dances the maenads, with their bare hands would tear apart some little animal that they had nourished at their breast. Then, as Euripides observed, they would enjoy 'the banquet of raw flesh.' On some occasions, it was said, they tore apart a tender child as if it were a fawn'"μ

One time the maenads got so involved in what they were doing they had to be rescued from a snow storm in which they were found dancing in clothes frozen solid. On another occasion a government official that forbade the worship of Dionysus was bewitched into dressing up like a maenad and enticed into one of their orgies. When the maenads discovered him, he was torn to pieces until only a severed head remained.μ

It is not totally clear whether the maenad dances were based purely on mythology and were acted out by festival goers or whether there were really episodes of mass hysteria, triggered perhaps by disease and pent up frustration by women living in a male-dominate society. On at least one occasion these dances were banned and an effort was made to chancel the energy into something else such as poetry reading contests.

Evidence of the maenads’ existence has been found in Greek inscriptions from various time periods. Apparently there really were groups of women who would reach such a state of delirium, under the influence of Dionysus’ priestly incarnation, that they were prepared to rip apart live animals and eat their raw flesh. [Source: David Hernández de la Fuente, National Geographic History, May 25, 2022]

Four Dionysus Festivals in Athens

The festivals of Dionysus had an important influence on life in Greece, as well as on its literature and art. There were four of these every year at Athens; in the month of Poseidon (February), the country Dionysia, called also “the lesser,” took place. Naturally this was a vine festival, as would result from the character of the god; but the common opinion, that it was to celebrate the vintage, is open to many objections, especially since the time of the feast seems too late for the vintage. It is more probable that the new wine was then tasted for the first time.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

This festival was not connected with any special place; country Dionysia were celebrated in every village, and not only in Attica, but everywhere in Greece where vines were cultivated, and it always bore the character of a cheerful national feast connected with fun and merry frolic. In the “Acharnians” of Aristophanes a peasant celebrates the festival alone with his family; it begins with prayer and a procession to the sacrifice, in which the daughter, as basket-bearer, carries the basket of offerings on her head; the slave with the Phallus, the symbol of fertility and the never extinct producing power of the earth, next follows; and the master of the house sings his merry phallic song, while his wife looks on at the procession from the roof of the house. What was done here on a small scale by a single family, we must assume was performed on a larger scale in the real ceremony by all the assembled villagers.

There were also other parts of the festival, especially the chorus, which stood round the altar during the sacrifice of the goat, and praised the god in speech and song, probably also in answering refrain; they sang the birth, sufferings, and death of Dionysus, and were the origin of the dithyramb as well as of the drama, since this latter, as is well known, owes its origin to the festivals of Dionysus. Often there were real dramatic representations at the lesser Dionysia; it was especially the custom for strolling actors on these occasions to perform before the country people old plays, which had been already represented in the towns. Among the other entertainments, along with the festive processions, choruses, and banquets, one is especially worthy of mention. This was a game in which the young people of the village hopped about on greased wine skins, and tried to push each other down, while the falls were greeted with laughter by the bystanders; those who succeeded in retaining their place received prizes. This entertainment, which may be set on a par with our own running in sacks, was customary, too, at other festivals of Dionysus.

The second Athenian festival of Dionysus was peculiar to Athens, but was probably only one of the country Dionysia transferred to the town; it was called Lenaea, after the place where it was usually held, the Lenaeon, in the suburb Limnae, and was held in the month of Gamelion (January). The name suggests a feast of wine-presses, which does not coincide with the time of the celebration; many attempts have been made to explain this difficulty, but without result. The festival, or at any rate a special part of it, bore the name Ambrosia, probably because they drank a great deal of the new wine to which they assigned this divine name; and, in fact, plentiful drinking was a characteristic of all the festivals of the wine god. A great banquet accompanied the festivities, for which the State provided everything, and there was also a solemn procession into the town, in which many people drove, amid jest and frolic, so that the “jokes from the car” became proverbial. In the Lenaeon, to which the procession first marched with the sacrificial animals, solemn dithyrambs were sung in competition, and the prize was a wreath of ivy; there were also dramatic representations, at which both old and new pieces were performed.

The third festival of Dionysus was the Anthesteria, in the month Anthesterion (February), which lasted three days, and was even more distinctly associated with the tasting of the new wine than the Lenaea. The first day of the festival bore the distinctive name of “Cask-opening” (πιθοιγία). It was essentially a family festival. The casks, with the new wine which was to be used next day for the banquet, were brought in by the servants and opened; the wine was drawn off into amphoras or other vessels, and naturally many a draught was drunk, and in particular the slaves had their share. For the Athenians, who always treated their slaves well, did not grudge them their fair share on this festive occasion, and when they offered their sacrifices at the Cask-opening, and helped to draw off the wine, they probably themselves filled a jar for their servants and workmen with the new gift of Bacchus. All other work ceased for this day and the next, and the children, too, had holidays. The old image of Dionysus, which was to make its solemn entry into the town in the procession of the following day, was also brought on this first day from its temple in the Nemaeon to a chapel in the outer Kerameikos.

Feast of Pitchers

But this festival was only a preparation for the principal day, called “The Feast of Pitchers,” which began at sunset — the time when all festivals commenced — with a great procession. Those who took part in it appeared wreathed and bearing torches (for the procession did not take place till dark) in the outer Kerameikos; children, too, except those under three years, took part in it, probably accompanied by their mothers, or in carriages, for many participants drove; and here, as in the country Dionysia, it was the custom to mock the passers-by from the carriage. In fact, this part of the festival bore the character of a merry carnival; many people appeared in costume as Horae, Nymphs, Bacchantes, etc., and crowded gaily around the triumphant car on which the statue of Dionysos-Eleutheros, which had been fetched from its temple on the previous day, was conducted to the town. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

On the way religious rites were observed at various places sanctified by legend. At one place the Basilinna, that is, the wife of the Archon Basileus, had to sit on the car next the statue of Dionysus, for on this day she was the bride of the god, and thus, on her wedding-car, she entered the Lenaeon, where a mystic sacrifice was offered for the welfare of the State in the innermost part of the temple, by the Basilinna, together with the fourteen ladies of honour appointed for this purpose by the Archo. These took a solemn oath to the queen before the ceremony took place, and in so doing followed an ancient formula inscribed on stone columns in the temple. After the sacrifice, with which other secret ceremonies were connected, followed the symbolical marriage of the Basilinna and Dionysus. While these sacred ceremonies, to which but few were admitted, were taking place in the interior of the temple, the other celebrants enjoyed themselves in different ways. On the next day the actual Pitcher Feast took place — the great banquet, with the drinking contest, that followed it. At this great public feast the Archon-Basileus was superintendent of the festival, but the State defrayed the expenses, originally, probably, in kind, but afterwards in such a way that each citizen received a fixed sum of money, and with this supplied his food and also the can of pure wine which stood in front of everyone, and gave its name to this day. Both the banquet and the drinking contest were probably held in the theatre in the Lenaeon, where the chief priest of Dionysus had to provide cushions, tables, and other conveniences. A proclamation by the herald, in ancient style, introduced the most interesting event — the drinking contest. At a signal given by a trumpet, all who took part in it set their pitchers to their mouths, and the judges allotted the victory to him who first emptied his; the prize consisted in a skin of wine, cakes, or something of the kind. Besides this public banquet there were also private hospitalities, provided by those who preferred to celebrate the day by themselves in the circle of a few intimate friends, and here, too, much drinking went on; the Sophists, in particular, who received their honorarium and presents on this day, were in the habit of inviting their acquaintances to a feast. Thus things went on merrily till the beginning of the night; then each guest took his pitcher and the wreath of fresh flowers which he had worn at the feast to the sanctuary of Dionysos-Eleutheros, that was divided off with a rope, and here the wreaths were handed to the priestess, and the remains in the pitcher poured out as a libation to the god.

Feast of Pots

The third day was called the “Feast of Pots”, from a sacrifice offered to Hermes Chthonios and the spirits of the dead, and here they observed the traditional custom of first sacrificing to those who had perished in the Flood of Deucalion. At these sacrifices, pots containing a number of vegetable substances cooked together, played an important part, and these dishes also constituted the meal of this day, on which no flesh was eaten. The ladies of honour also offered sacrifices to Dionysus at sixteen specially erected altars, and there were probably other ceremonies connected with this; in fact, this third day of the “Anthesteria,” with its serious ceremonial, formed a strong contrast to the merriment of the previous days, and suggests a similar contrast between our Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

But even on the “Day of Pots” there was no lack of amusements for the people; sacred choruses were conducted by the poets, but it does not seem that any regular dramas were performed. Possibly dramatic contests had been the custom in earlier times, or else only such competitions were allowed as determined the admission of the poets and actors, who won the prize on this occasion, to competition at the greater Dionysia. The chief festival of Dionysus in Attica was the greater, or city Dionysia, in Elaphebolion (March), which lasted at least five days, and perhaps even longer, and whose chief importance consisted in the plays acted during these days. The first solemn ceremony of the greater Dionysia was in honor of Aesculapius, to whom a public sacrifice was brought. Here, too, there was a procession, in which the statue of Dionysos-Eleutheros was carried; whether it was the old wooden image which was carried at the Lenaea, or the new statue by Alcamenes, is uncertain, but the latter was of gold and ivory, and, therefore, not easily portable; in any case the statue was fetched from the sanctuary at Lenaea, and carried by torchlight to the theatre of Dionysus, where it was set up in the orchestra. On the following day came the procession, in which the sacrificial animals, as well as the presents sent by allies, probably appeared. The procession stopped in the market place, and a cyclical chorus performed a dance round the altar to the Delphic gods who stood there. When they passed on they seem to have fetched away the Dionysus statue from the theatre, and carried it once more in a festive procession to the sanctuary in the Lenaeon.

This procession was followed by sacrificial banquets, and on the other days plentiful feasting was also a part of the celebration. The following days were chiefly occupied by the performances, which seem to have followed in some such order as this: First of all, lyric choruses; both men and boys entered, and the expenses, which were heavy, were defrayed by citizens acting as choragi. Perhaps this day was concluded by a “Comus,” as public processions of this kind often followed common banquets, and since it was the god of wine who was specially to be honored, it was, no doubt, very splendidly equipped. The next days were occupied with representations of tragic tetralogies and comedies; it is not certain whether these lasted two or more days, but it is probable that they continued for three days, and that on each of these a tetralogy was performed in the morning and a comedy in the afternoon. On the evening of the third day of the performances, which concluded the whole festival, the prizes were distributed; in these musical contests they consisted of bulls and tripods. These last were often set up in a public street on a high pedestal by the victors, and hence it acquired the name “Street of Tripods.”

Poussin's Bacchanal

Did Bacchus Cults Really Carry Out Ritual Murder

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: According to the Roman historian Livy (who wrote a century and a half after the events), sex and alcohol were just the gateway drugs. The Bacchants, he charged, had brought to Rome a whole host of more serious crimes. Livy’s soap opera-style story of the discovery of their true nature and the subsequent investigation describes how at celebrations, after everyone had had their fill of wine and bawdy conversations, people would indulge in every kind of pleasure depending on where their interests lay. Gay sex between men is prominently mentioned in these descriptions, but Livy wasn’t talking just about the orgies. “From the same place, too,” he writes, “proceeded poison and secret murders, so that in some cases, not even the bodies could be found for burial. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, June 8, 2019]

Many of their audacious deeds were brought about by treachery, but most of them by force; it served to conceal the violence, that, on account of the loud shouting, and the noise of drums and cymbals, none of the cries uttered by the persons suffering violence or murder could be heard abroad.” The music, he says, which could be heard throughout Rome in the evenings was intended to drown out the noise of people being murdered.

Livy goes on to tell us a story at the end of which a former Bacchant describes the secret mysteries of Bacchus to the consul of Rome. Apparently men who would not submit to sexual congress with other men were sacrificed to the gods, and the cult initiated people only under the age of 20 in order to win converts who were still young and impressionable. Comparatively pedestrian crimes like perjury and forging wills were also being committed. When these crimes were discovered the Roman senate agreed, without debate, to take action: many practitioners were killed or imprisoned, places of worship were destroyed, and a decree was leveled against the cult of Bacchus. This decree, passed in 186 and known as the senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus, restricted gatherings to a mere handful of attendees who could meet only with a special license. Apparently many members committed suicide to avoid punishment.

The crimes of the Bacchants seem a great deal like improbable slander. The idea of ritual murders taking place regularly in Rome is shocking but it doesn’t seem particularly believable. Surely those who were murdered would be missed? Given that most of the accusations seem to be sensationalized we have to ask, what went wrong for the Bacchants? Why were the Romans troubled by their existence and why did they suddenly decide to take unprecedented steps to suppress the cult after centuries of happily tolerating them?

At least part of the problem for historians studying this question is that Livy is writing long after the events and with his own agenda in mind. Part of Livy’s motivation appears to have been a xenophobic fear about foreign corruption. As Timothy Luckritz Marquis has argued in Transient Apostle, those who wrote about Dionysiac rituals emphasized the “foreignness” and “Easternness” of the religion. For Livy, who believed that foreign influences had infected and morally corrupted the otherwise pristine Roman Republic, the cult of Bacchus was a prime example of the dangers of foreign influences. Among other concerns, Livy worries that men initiated into the cult of Bacchus would grow “soft” and unfit for military service. This is a theme for Livy throughout his history; foreign luxuries corrupt and undermine the moral fabric of society.

For those in the senate who actually outlawed the cult, there may have been other motivations. It was not just the cult of Bacchus’s chaotic nature, but also its sophisticated organizational structures, that made it worrisome to the authorities. The Bacchants had a common fund, multiple administrative ranks, several meeting places, and swore oaths of allegiance. A well-organized independent organization like this made the authorities uneasy. To be sure there were other kinds of organizations that served as vehicles for religious practice, but unlike, say, a group of artisans or merchants, the cult of Bacchus drew indiscriminately from every strata of society and walk of life. A nationwide foreign organization that held regular meetings (apparently five a month) and could subvert public morality was inherently threatening.

A number of prominent classicists describe the investigation into (and subsequent legislation restricting) the cult of Bacchus as something of a set-up. It was an example of realpolitik in which the Bacchants were used to make a statement to rivals in the region. As distinguished classicist Erich Gruen has written “it was a staged operation” in which the senate attempted to “claim new prerogatives in the judicial sphere, in the regulation of worship, and in the extension of authority in Italy.” In other words, Roman authorities knew the basic character of the cult of Bacchus long before they decided to ‘investigate’ them on exaggerated charges. To be sure they were protecting their society from decay, corruption, and immorality but they were also using the Bacchants to assert and extend their power. Targeting small religious groups as a display of power can help solidify a government’s authority and power.

Livy’s Account of Bacchus Cult Murder and the Crackdown on the Cult

Describing the Senatusconsultum de Bacchanalibus in Italy, Livy wrote in “History of Rome”, Book 39. 8-19 (186 B.C.): "During the following year, the consuls Spurius Postumius Albinus and Quintus Marcius Philippus were diverted from the army and the administration of wars and provinces to the suppression of an internal conspiracy.... A lowborn Greek came first into Etruria [Tuscany], a man who was possessed of none of the numerous arts which [the Greeks] have introduced among us for the cultivation of mind and body. He was a mere sacrificer and a fortuneteller–not even one of those who imbue men’s minds with error by preaching their creed in public and professing their business openly; instead he was a hierophant of secret nocturnal rites. At first these were divulged to only a few. Then they began to spread widely among men, and women. To the religious content were added the pleasures of wine and feasting–to attract a greater number. [Source: (Livy History of Rome Book 39. 8-19: 186 B.C., John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

“When they were heated with wine and all sense of modesty had been extinguished by the darkness of night and the commingling of males with females, tender youths with elders, then debaucheries of every kind commenced. Each had pleasures at hand to satisfy the lust to which he was most inclined. Nor was the vice confined to the promiscuous intercourse of free men and women! False witnesses and evidence, forged seals and wills, all issued from this same workshop. Also, poisonings and murders of kin, so that sometimes the bodies could not even be found for burial. Much was ventured by guile, more by violence, which was kept secret, because the cries of those calling for help amid the debauchery and murder could not be heard through the howling and the crash of drums and cymbals.

“This pestilential evil spread from Etruria [Tuscany] to Rome like a contagious disease. At first, the size of the city, with room and tolerance for such evils, concealed it. But information at length reached the Consul Postumus.... Postumus laid the matter before the Senate, setting forth everything in detail-first the information he had received; and then, the results of his own investigations. The Senators were seized by a panic of fear, both for the public safety (lest these secret conspiracies and nocturnal gatherings contain some hidden harm or danger) and for themselves individually (lest some relatives be involved in this vice). They decreed a vote of thanks to the Consul for having investigated the matter so diligently and without creating any public disturbance. Then they commissioned the consuls to conduct a special inquiry into the Bacchanalia and nocturnal rites. They directed them to see to it that Aebutius and Faecenia suffer no harm for the evidence they had given, and to offer rewards to induce other informers to come forward; the priests of these rites, whether men or women, were to be sought out not only in Rome but in every forum and conciliabulum, so that they might ‘be at the disposal of’ the consuls. Edicts were to be published in the City of Rome and throughout Italy, ordering that none who had been initiated into the Bacchic rites should be minded to gather or come together for the celebration of these rites, or to perform any such ritual. And above all, an inquiry was to be conducted regarding those persons who had gathered together or conspired to promote debauchery or crime.

“These were the measures decreed by the Senate. The consuls ordered the Curule Aediles to search out all the priests of this cult, apprehend them, and keep them under house arrest for the inquiry; the Plebeian Aediles were to see that no rites were performed in secret. The Three Commissioners (Tresviri Capitales) were instructed to post watches throughout the City, to see to it that no nocturnal gatherings took place and to take precautions against fires. And to assist them, five men were assigned on each side of the Tiber, each to take responsibility for the buildings in his own district....

“The Consuls then ordered the Decrees of the Senate to be read [in the Assembly] and they announced a reward to be paid to anyone who brought a person before them, or, in the absence of the person, reported his name. If anyone took flight after being named, the Consuls would fix a day for him to answer the charge, and on that day, if he failed to answer when called, he would be condemned in absentia. If any person were named who was beyond the confines of Italy at the time, they would set a more flexible date, in the event that he should wish to come to Rome and plead his case. Next, they ordered by edict that no person be minded to sell or buy anything for the purpose of flight; that no one harbor, conceal, or in any way assist fugitives.... Guards were posted at the gates, and during the night following the disclosure of the affair in the Assembly, many who tried to escape were arrested by the Tresviri Capitales and brought back. Many names were reported, and some of these, women as well as men, committed suicide. It was said that more than 7,000 men and women were implicated in the conspiracy.”

“Next the Consuls were given the task of destroying all places of Bacchic worship, first at Rome, and then throughout the length and bradth of Italy–except where there was an ancient altar or a sacred image. For the future, the Senate decreed that there should be NO Bacchic rites in Rome or in Italy. If any person considered such worship a necessary observance, that he could not neglect without fear of committing sacrilege, then he was to make a declaration before the Praetor Urbanus, and the Praetor would consult the Senate. IF permission were granted by the Senate (with at least one hundred senators present), he might perform that rite–provided that no more than five persons took part in the ritual, and that they had no common fund and no master or priest...."”

See “The Senatus Consultum de Bacchanalibus, 186 B.C.” by “Livy, History of Rome, Book XXXIX, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu

Bacchanal

Dionysian Theater

David Hernández de la Fuente wrote in National Geographic History: In Hellenic culture, Dionysus embodied a symbol of communal cohesion and reconciliation, closely connected with the theater. Every March, the city of Athens would hold a festival known as the Great Dionysia (also called the City Dionysia). Dating as early as the sixth century B.C., this dramatic festival lasted as many as six days. On the first day, a procession would open the festival as a statue of Dionysus was borne to his theater. After the day’s performances, a bull would be sacrificed and a feast held. [Source: David Hernández de la Fuente, National Geographic History, May 25, 2022]

In the days that followed, ancient Greece’s playwrights would present their works — tragedies, comedies, and satyric drama — and compete for top honors. (According to tradition, tragedy was originally related to songs from the Dionysian feast of the tragos, goat, and oidos, song). Actors who gave the best performances would also be awarded prizes. Those taking first place would be given wreaths of ivy, in a nod to the patron god of wine.

The chorus of Euripides’ tragedy The Bacchae, written around 405 B.C., evokes the Dionysian mystery rites: "Blessed is he who, being fortunate and knowing the rites of the gods, keeps his life pure and has his soul initiated into the Bacchic revels, dancing in inspired frenzy over the mountains with holy purifications, and who, revering the mysteries of great mother Kybele, brandishing the thyrsos, garlanded with ivy, serves Dionysus."

Euripides describes the ecstasy that Dionysus unleashes among his retinue: "Go, Bacchae, go, Bacchae . . . sing of Dionysus, beneath the heavy beat of drums, celebrating in delight the god of delight with Phrygian shouts and cries, when the sweet-sounding sacred pipe sounds a sacred playful tune suited to the wanderers, to the mountain, to the mountain!”

Located at the foot of the Acropolis in Athens, the Theater of Dionysus was first erected between the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. After subsequent renovations, it was enlarged to seat as many as 17,000 spectators. Pergamon, an ancient city in Asia Minor that is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, built a massive theater with a capacity for 10,000 spectators. The seating is set into the hillside and faces a temple dedicated to Dionysus, god of the theater.

See Separate Article: DRAMA IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Dionysius in the Bacchae by Euripides

Euripides wrote in “The Bacchae,” 677-775: The Messenger said: “The herds of grazing cattle were just climbing up the hill, at the time when the sun sends forth its rays, warming the earth. I saw three companies of dancing women, one of which Autonoe led, the second your mother Agave, and the third Ino. All were asleep, their bodies relaxed, some resting their backs against pine foliage, others laying their heads at random on the oak leaves, modestly, not as you say drunk with the goblet and the sound of the flute, hunting out Aphrodite through the woods in solitude. [Source: Euripides. “The Tragedies of Euripides,” translated by T. A. Buckley. Bacchae. London. Henry G. Bohn. 1850.

“Your mother raised a cry, standing up in the midst of the Bacchae, to wake their bodies from sleep, when she heard the lowing of the horned cattle. And they, casting off refreshing sleep from their eyes, sprang upright, a marvel of orderliness to behold, old, young, and still unmarried virgins. First they let their hair loose over their shoulders, and secured their fawn-skins, as many of them as had released the fastenings of their knots, girding the dappled hides with serpents licking their jaws. And some, holding in their arms a gazelle or wild wolf-pup, gave them white milk, as many as had abandoned their new-born infants and had their breasts still swollen. They put on garlands of ivy, and oak, and flowering yew. One took her thyrsos and struck it against a rock, from which a dewy stream of water sprang forth. Another let her thyrsos strike the ground, and there the god sent forth a fountain of wine. All who desired the white drink scratched the earth with the tips of their fingers and obtained streams of milk; and a sweet flow of honey dripped from their ivy thyrsoi; so that, had you been present and seen this, you would have approached with prayers the god whom you now blame.

Dionysos

“We herdsmen and shepherds gathered in order to debate with one another concerning what strange and amazing things they were doing. Some one, a wanderer about the city and practised in speaking, said to us all: “You who inhabit the holy plains of the mountains, do you wish to hunt Pentheus' mother Agave out from the Bacchic revelry and do the king a favor?” We thought he spoke well, and lay down in ambush, hiding ourselves in the foliage of bushes. They, at the appointed hour, began to wave the thyrsos in their revelries, calling on Iacchus, the son of Zeus, Bromius, with united voice. The whole mountain revelled along with them and the beasts, and nothing was unmoved by their running.

“Agave happened to be leaping near me, and I sprang forth, wanting to snatch her, abandoning the ambush where I had hidden myself. But she cried out: “O my fleet hounds, we are hunted by these men; but follow me! follow armed with your thyrsoi in your hands!” We fled and escaped from being torn apart by the Bacchae, but they, with unarmed hands, sprang on the heifers browsing the grass. and you might see one rending asunder a fatted lowing calf, while others tore apart cows. You might see ribs or cloven hooves tossed here and there; caught in the trees they dripped, dabbled in gore. Bulls who before were fierce, and showed their fury with their horns, stumbled to the ground, dragged down by countless young hands. The garment of flesh was torn apart faster then you could blink your royal eyes. And like birds raised in their course, they proceeded along the level plains, which by the streams of the Asopus produce the bountiful Theban crop. And falling like soldiers upon Hysiae and Erythrae, towns situated below the rock of Kithairon, they turned everything upside down. They were snatching children from their homes; and whatever they put on their shoulders, whether bronze or iron, was not held on by bonds, nor did it fall to the ground. They carried fire on their locks, but it did not burn them. Some people in rage took up arms, being plundered by the Bacchae, and the sight of this was terrible to behold, lord. For their pointed spears drew no blood, but the women, hurling the thyrsoi from their hands, kept wounding them and turned them to flight—women did this to men, not without the help of some god. And they returned where they had come from, to the very fountains which the god had sent forth for them, and washed off the blood, and snakes cleaned the drops from the women's cheeks with their tongues.

“Receive this god then, whoever he is, into this city, master. For he is great in other respects, and they say this too of him, as I hear, that he gives to mortals the vine that puts an end to grief. Without wine there is no longer Aphrodite or any other pleasant thing for men. I fear to speak freely to the king, but I will speak nevertheless: Dionysus is inferior to none of the gods.”

Pentheus said: “Already like fire does this insolence of the Bacchae blaze up, a great reproach for the Hellenes. But we must not hesitate. Go to the Electran gates, bid all the shield-bearers and riders of swift-footed horses to assemble, as well as all who brandish the light shield and pluck bowstrings with their hands, so that we can make an assault against the Bacchae. For it is indeed too much if we suffer what we are suffering at the hands of women.”

Dionysus said: “Pentheus, though you hear my words, you obey not at all. Though I suffer ill at your hands, still I say that it is not right for you to raise arms against a god, but to remain calm. Bromius will not allow you to remove the Bacchae from the joyful mountains.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum. The human sacrifice images are from The Guardian

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024