Home | Category: Literature and Drama

FAMOUS ANCIENT GREEK PLAYWRIGHTS

Greece's most famous dramatists — Aeschylus (525-426 B.C.), Sophocles (496-406 B.C.), Aristophanes (450-357 B.C.) and Euripides (485-406 B.C.) — are associated with the Golden Age of Greece. They were based in Athens and competed frequently in the drama contests. Aeschylus won the prize thirteen times and Sophocles won it 20 times, defeating Aeschylus once and losing to Euripides on another occasion. Teachers and scholars of drama often talk about the four greatest playwrights of all time with three being Greek — Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides — with only Shakespeare allowed to join them. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Marco Merola wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Going to the theater was an essential part of ancient Greek civic and religious life. Plays such as the tragedies of Aeschylus and Euripides, the comedies of Aristophanes and Menander, and likely numerous other works that have not survived, were regularly staged at religious festivals. Masked actors and a chorus whose role was to comment on the play’s action in song, dance, and verse entertained festivalgoers and paid honor to the gods. “Since the very beginning of Greek civilization, a theater was always a religious building housed in a sanctuary,” says archaeologist Luigi Maria Caliò of the University of Catania. “In the Greek world, everything was related to holiness, and theaters were built in sacred areas.” [Source: Marco Merola, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019]

Little is known about the lives of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Based on the content of their plays, some scholars have suggested that Sophocles and Euripides were gay. Of the 92 plays written by Euripides only 18 remain, and of the 122 by Sophocles and 82 by Aeschylus only seven from each playwright are with us today. No works exist by Agathon, described as most innovative Greek playwright and the only one who didn't adapt well known stories.μ

RELATED ARTICLES:

DRAMA IN ANCIENT GREECE: ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, TYPES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THEATERS IN ANCIENT GREECE: STRUCTURES, STAGES, SETS, MACHINES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK THEATER PERFORMANCES: CONTESTS, ACTORS, MASKS, COSTUMES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDIES: PLOTS, TYPES, STRUCTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

ARISTOPHANES AND ANCIENT GREEK COMEDIES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Greek Tragedy” (Penguin Classics) by Aeschylus, Euripides, Sophocles, Shomit Dutta Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy” by P. E. Easterling Amazon.com;

“Greek Tragedy (Routledge Classics) by H.D.F. Kitto and Edith Hall

Amazon.com;

“Poetics” (Penguin Classics) by Aristotle Amazon.com;

“A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theater” by Graham Ley Amazon.com;

“Guide To Greek Theatre And Drama (Plays and Playwrights)” by Kenneth McLeish and Trevor R. Griffiths (2003) Amazon.com;

“Theatre in Ancient Greek Society” by J. R. Green (1996) Amazon.com;

“Looking at Greek Drama: Origins, Contexts and Afterlives of Ancient Plays and Playwrights” by David Stuttard (2024) Amazon.com;

“Costume in Greek Tragedy” by Rosie Wyles (2011) Amazon.com;

“Nothing to Do with Dionysos? Athenian Drama in Its Social Context” by John J. Winkler and Froma I. Zeitlin (1990) Amazon.com;

“Performance Culture and Athenian Democracy” by Simon Goldhill and Robin Osborne (1999) Amazon.com;

Aeschylus: “Prometheus Bound and Other Plays: Prometheus Bound, The Suppliants, Seven Against Thebes, The Persians (Penguin Classics) by Philip Vellacott and Aeschylus (1961) Amazon.com;

“The Oresteia: Agamemnon; The Libation Bearers; The Eumenides” by Aeschylus, Robert Fagles, et al. (1984) Amazon.com;

Euripides: “The Bacchae and Other Plays (Penguin Classics) by Euripides Amazon.com;

“Medea and Other Plays” (Penguin Classics) by Euripides and Philip Vellacott (1963) Amazon.com;

“The Trojan Women and Other Plays (Oxford World's Classics) Reissue Edition” by Euripides (1928) Amazon.com;

“Three Plays: Alcestis / Hippolytus / Iphigenia in Taurus” by Euripides and Philip Vellacott (1995) Amazon.com;

Sophocles: “The Oedipus Cycle: Oedipus Rex, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone”

by Sophocles, Dudley Fitts, et al. (2002) Amazon.com;

“Electra and Other Plays (Penguin Classics) by Sophocles, David Raeburn, et al. (2008) Amazon.com;

“Sophocles II: Ajax, The Women of Trachis, Electra, Philoctetes, The Trackers” by . Sophocles, Mark Griffith, et al. (2013) Amazon.com;

Aeschylus

Aeschylus (525-456 B.C.) was the earliest of the three great Greek tragic dramatists (the others are Sophocles and Euripides). He introduced the second actor into the play. He is thought to have written 80-90 plays, of which 7 survive. They include “The Suppliants” (prob. 463 B.C.) And Oresteia trilogy (458 B.C.) Aeschylus (525-456 B.C.) was the earliest and, some say, the greatest dramatic poet. He introduced the Second Actor transforming, in effect, monologue into dialogue and he reduced the size of the chorus, moving from an unwieldy 50 to a more manageable and numerically-desirable 12. When he was asked to write his epitaph he chose not to mention his glorious writing career but instead pointed out his presence and his contribution at the defining Battle of Marathon. Several of his plays survive, such as: The Persians, Prometheus Bound and The Oresteia. [Source: Canadian Museum of History <|]

Aeschylus introduced the idea of tragedy, but he did not involve his characters in a conflict. Instead the main character in his plays was a solitary hero wrestling with himself or with destiny. In his early plays action centers around a chorus. In his later plays a tragic hero appears. Aeschylus is also "famous for his knottiness, his clotted images and riddling compound words."

Plays by Aeschylus

WEB MIT Classics Archive: Aeschylus classics.mit.edu

”The Suppliants” (probably 463 B.C.) Perseus Perseus.org

”The Suppliant Women” (467 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Oresteia (Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, Eumenides)” Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Oresteia Trilogy” (458 B.C.)

”Agamemnon” Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece: sourcebooks.fordham.edu

”The Choephori”

”Eumendides” Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece: sourcebooks.fordham.edu

”Prometheus Bound” (47 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Prometheus Bound”, trans E. B. Browning Wikisource en.wikisource.org

”The Seven Against Thebes” (467 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”The Persians” (472 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”The Persians” (472 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”The Persians” (472 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”The Persians” (472 B.C.), translated by C. A. E. Luschnig” Diotima Diotima

Many of Aeschylus’ plays were trilogies. The only one that remains, “The Oresteia,” consists of three parts: “Agamemnon” , “Choephori” and “Eumenides” set during the Trojan Wars. He also wrote “Persae” , a victory song connected with the defeat of the Persians, and “Prometheus Bound” , a classic retelling of the Prometheus myth. [Recommended Books: “The Oresteia” by Aeschylus, new translation by Ted Hughes (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999) and “The Oresteia” by Aeschylus, a brash and slangy translation by Anne Carson (Faber & Faber, 2009).

Sophocles

Sophocles (496-406 B.C.) was the second of the great tragic poets. He wrote over 100 plays, but only seven complete ones survive, including Oedipus the King and Antigone. Sophicles was a product of the Age of Pericles (they were close friends) and his career overlapped that of Aeschylus and Euripides. Aristotle considered him to be the best ever in his field. He introduced the Third Actor, an innovation which enlarged the scope and dramatic impact of the play. Sophocles developed more complex plots and introduced more characters and more philosophical themes. He is considered the most Greek of the Greek playwrights. His plays include “Oedipus” (see below), “Ajax” and “Electra” .

Sophocles was a general. He wrote his plays, some which deal with warfare, 2,500 years ago, during a century of war and plague in Greece. Many were performed as part of the spring City Dionysia, the dramatic festival of Athens at which the great tragedies and comedies of the age were performed for every citizen. The audiences for whom these plays were performed were undoubtedly composed of citizen-soldiers. Also, probably many of the the performers were were likely veterans or cadets. [Source: Jeff MacGregor, The Healing Power of Greek Tragedy”Smithsonian magazine, November 2017, “ smithsonianmag.com ]

Bryan Doerries is director and co-founder of the Brooklyn-based Theater of War Productions, which bills itself as “an innovative public health project that presents readings of ancient Greek plays, including Sophocles’ Ajax, as a catalyst for town hall discussions about the challenges faced by service men and women, veterans, their families, caregivers and communities.” “Seen through this lens,” he told Smithsonian magazine, “ancient Greek drama appears to have been an elaborate ritual aimed at helping combat veterans return to civilian life after deployments during a century that saw 80 years of war. Plays like Sophocles’ Ajax read like a textbook description of wounded warriors, struggling under the weight of psychological and physical injuries to maintain their dignity, identity and honor.”

The climatic scene of “Ajax” goes:

Death oh Death, come now and visit me —

But I shall miss the light of day and the

sacred fields of Salamis, where I played

as a boy, and great Athens,

and all of my

friends. I call out to you springs and rivers

fields and plains who nourished me during these

long years at Troy.

These are the last words you will hear Ajax speak.

The rest I shall say to those who listen

in the world below.

Ajax falls on his sword.

A few seconds later, his wife Tecmessa finds him and sets loose her terrible cry. That cry echoes down 2,500 years of history, out of the collective unconscious. Men and women and gods, war and fate, lightning and thunder and the universal in everyone.

Plays by Sophacles

WEB MIT Classics Archive: Sophocles classics.mit.edu

”Ajax” (440 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Antigone” (442 B.C.) Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece: sourcebooks.fordham.edu

See 2ND Study Guide”Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Antigone” Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Antigone” (442 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Antigone”, translation and notes by Wm. Blake Tyrrell and Larry J. Bennett Diotima Diotima . A much more modern translation, with extensive annotation.

”Ajax” Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Ajax”, translated by C. A. E. Luschnig Diotima Diotima

”Electra” (between 418-410 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Philoctetes” (409 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Oedipus the King: (430 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

See 2ND Study Guide” Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Oedipus at Colonus” (405 or 40 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Trachiniae (Women of Trachis)” (430 B.C.) Internet Archive Internet Archives

”Trachiniae:, translated by Robert M. Torrance, Internet Archive Internet Archives

Oedipus

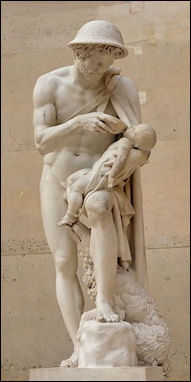

Oedipus Phorbas

Oedipus, the King of Thebes, is the most famous tragic Greek character. He killed his father and married his mother and solved the riddle of the sphinx , and gave Freud a name for one of his complexes. Sophocles wrote a trilogy that covers Oedipus and his children: “Oedipus the King,” “Oedipus of Colonus” and “Antigone”.

The Oedipus story begins with Oedipus's father, King Laius learning from an oracle that his son will kill him. He therefore has his newborn son's feet pierced and bound up and left on Mount Cithaeron to die of exposure. A shepherd finds the child, names him Oedipus, meaning swollen feet, and takes him to the King of Corinth, who rears him like a son. When Oedipus is told by an oracle that he will murder his father, he leaves Corinth, thinking its king is his father.

On his journey Oedipus comes across a charioteer, whose servant rudely orders Oedipus out of the way. Oedipus get angry and kills the servant and his msater, without realizing the master is his real father, Ling Laius. Around this time a terrible sphinx appears in Thebes and tells anyone who can not answer the riddle of the sphinx — What animals walks on all fours in the morning, two at noon and three at night? — will be devoured. Oedipus figures out he answer — man as a crawling baby, upright adult an old man with a cane. Afterwards the sphinx kills herself by leaping off a cliff.

As a reward Oedipus is made King of Thebes and marries his mother. Not long afterwards Oedipus learns the truth: he was killed his father and married his mother. Horrified, he puts out his eyes while his mother hangs herself with her veil. Oedipus becames an outcast but is cared for until his death by his sister Antigone. Antigone is presented as paragon of self sacrifice, which comes out more graphically in her own play.

Oedipus Rex

Oesdipus Rex, also known by its Greek title, Oedipus Tyrannus or Oedipus the King, is the first of Oedipus trilogy. ,It begins with Oedipus’s father Laius being left an orphaned minor by his father Labdacus Amphion and Zethus rule Thebes (Build the Cadmeia) and exile Laius. Laius goes to live in Elis (PISA) with King Pelops (son of Tantalus son of Zeus). He becomes very good friends with young Chrysippus, youngest child of King Pelops Laius and Chrysippus run away together (or Laius rapes Chrysippus). Pelops curses Laius. [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Laius returns to Thebes and becomes King. marries his cousin (?) Jocasta, but they are childless Laius goes to Delphi and intends to ask Apollo's advice; Apollo announces that Laius will have a child who will kill him. Laius and Jocasta have a baby son (Oedipus) whom they plan to kill. The royal shepherd is ordered to dispose of the child on Mt. Cithaeron. Instead he gives Oedipus to the royal Corinthian shepherd.

The Royal Corinthian Shepherd takes the child back to the childless king and queen of Corinth (Polybus and Merope), who adopt him. At about the age of 18, at a dinner party, one of Oedipus' friends makes a rude remark about his not being a real Corinthian but only adopted. Oedipus is shocked and shamed, and goes off to Delphi to ask Apollo about the truth. Apollo tells Oedipus he is doomed to kill his father and sleep with his mother.

Oedipus kills his father (within hours, at The Three Ways). He Oedipus kills the Sphinx on the way from the Three Ways to Thebes Oedipus is received at Thebes as a national hero, and invited to marry the recently widowed queen Jocasta. Oedipus and Jocasta have four children: Eteocles and Polyneices, Antigone and Ismene.

As the first Oedipus play (Oedipus Rex) opens, there is sterility and a plague at Thebes; Oedipus sends to Delphi to ask Apollo what is wrong. Apollo sends a reply that they should find King Laius' murderer and then either kill him (retaliation, vengeance) or expel him from Theban territory. A messenger arrives from Corinth to announce that the King of Corinth is dead. Oedipus learns that he is not the son of the King of Corinth but a Theban. The Royal Theban Shepherd (who gave Oedipus to the Royal Corinthian Shepherd) is summoned and tells Oedipus who his parents really are. As this is happening, Jocasta runs off stage and hangs herself in her bedroom (like Phaedra). Oedipus runs after her, to kill her, but is too late. Shamed at his ancestry and predicament, he blinds himself.

Oedipus of Colunus

After consultation, it is decided to expel Oedipus from Thebes. His two sons Eteocles and Polyneices, agree, as does his brother-in-law (Uncle) Creon. Daughter Antigone goes with Oedipus. Oedipus comes to Colonus in Attica, to a Grove of the Furies. He is given hospitality by King Theseus. Apollo reveals to the Thebans that whoever possesses the person of Oedipus is fated to win a war at Thebes. Eteokles, king of Thebes, sends Uncle Creon to get Oedipus back. Polyneices, King-elect of Thebes (in exile in Argos), comes looking for Oedipus. [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Oedipus is given sanctuary at Colonus (a country district in Athens, about ten miles outside of town along the main road to Eleusis). At Colonus there is a Grove of the Furies, a shrine of Demeter, and a shrine of Poseidon. King Theseus, who happens to be coming to the shrine of Poseidon to sacrifice, personally intervenes when Uncle Creon tries to kidnap Oedipus. Oedipus curses his sons for their callousness and self-interest..Polyneices, who accepts the curse and the inevitability of his death, asks his sister Antigone (who is also his aunt) to be sure that he is given a proper burial. She takes an oath to do so. Thunder and portents are heard from the sky: Oedipus knows that it is his last moment on earth. Oedipus dies.

Antigone

It is decided that the brothers will share the throne of Thebes, alternating one year each. Eteocles goes first, and is supported by Uncle Creon. The elder brother Eteocles refuses to resign the kingship to Polyneices at the end of the first year of the Royal Condominium. A civil war breaks out, with Polyneices trying to recruit an army from Argos (Aeschylus, The Seven against Thebes). [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

The war at Thebes — the Seven Against Thebes — results in the self-sacrifice of Creon's son Menoecius; (b) the deaths in combat of both of Oedipus' sons. Antigone returns to Thebes to fulfill her oath and family obligations. But in the meantime Uncle Creon has been made tyrannos of Thebes (in some versions he is only Regent, for Eteocles' infant son Laodamas), and he issues an edict that he will punish with burial alive anyone who dares to bury the body of the traitor Polyneices (an act of hybris on his part, as well as taking an oath without realizing its consequences).

Protests come from the Theban elders and from Creon's own son Haemon. Antigone and Haemon (who were betrothed a long time before) fall in love. Antigone buries Polyneices, and is found out by Creon. Antigone is buried alive. Haemon hides in the cave ahead of time, intending to break out when the walling-in is done, and then to run away with Antigone and live happily ever after. Antigone has not been so informed, and therefore hangs herself as soon as she is put in the cave. When Haemon discovers this unhappy fact, he commits suicide too.

King Creon has a sudden change in heart and orders Antigone released. But he finds her dead, and his son too. A messenger tells Queen Eurydice (Creon's wife) that her son is dead. She curses Creon, goes into the Royal Marriage chamber, and hangs herself. Theseus invades Thebes and forces Creon to allow the burial of the various Argive dead. Creon's daughter Megara marries the son of Alcmene and Amphitryon (really of Zeus) Herakles. Creon is assassinated by L ykos the Younger, a descendant of the Lykos of Thebes who was the successor in the kingship immediately after Labdacus. Lykos was killed by Herakles. Laodamas ruled Thebes until it was destroyed by the Epigonoi. Creon's son Lycomedes served in the Trojan War.

Climax of Antigone

Antigone and Oedipus

The climatic scene from “Antigone” goes:

CREON

Tell me — and be careful with your words —

were you aware of my proclamation forbidding

the body to be buried?

ANTIGONE

Yes. I knew it was a crime.

CREON

And you still dared to break the law.

ANTIGONE

I didn’t know your laws were more powerful than

divine laws, Creon. Did Zeus make a proclamation,

too? I wasn’t about to break an unwritten rule of

the gods on account of one man’s whim. Of course,

I knew I would some day die. And if that day is

today, then I count myself lucky. It is better to die

an early death than live a long life surrounded by

evil men. So don’t expect me to get upset when you

sentence me to death. If I had allowed my own brother

to remain unburied, then you might see me grieving.

What’s wrong? You seem puzzled. Perhaps you think

I’ve rushed to action without considering the

consequences? Well, maybe it’s you who has rushed to

action. Either way, the question remains: Do you have the guts

to follow through?

CREON

I see you’ve inherited your father’s charm.

Citizens, I say that she is a man and I am not,

if she gets away with breaking the law and boasting

about her crime. I don’t care if she’s my niece, she

and her sister will both be put to death, for

I hold her sister equally responsible for planning

this burial. Call her. She’s right inside. I just saw

Creon orders Antigone put to death, walling her up in a small cave where she eventually commits suicide. As does Creon’s own son, betrothed to marry her. Then Creon’s wife, when she learns of her son’s death. It is a chain of tragedies forged by Creon’s own stubbornness. [Source: Jeff MacGregor, Smithsonian magazine, November 2017]

Euripides

Euripides (c.485-406 B.C.) was a younger contemporary of Sophocles, and third of the great tragic playwrights. He introduced deus ex machina as a plot device. According to the Euripides was a prolific playwright crafting 92 plays of which seventeen survive including Medea, The Trojan Women and The Children of Herakles. He found the chorus to be a distraction and minimized its role. He also introduced a new element ( the prologue) which provided the audience with a preview of what is about to happen. Success came to Euripides late in life and that may have made him somewhat introspective and antisocial. [Source: Canadian Museum of History ]

Euripides

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “Euripides (480-406 B.C.), the great Greek dramatic poet, was born in 480 B.C., on the very day, according to the legend, of the Greek victory at Salamis, where his Athenian parents had taken refuge; and a whimsical fancy has even suggested that his name-son of Euripus-was meant to commemorate the first check of the Persian fleet at Artemisium. His father Mnesarchus was at least able to give him a liberal education; it was a favourite taunt with the comic poets that his mother Clito had been a herbseller.... At first he was intended, we are told, for the profession of an athlete,- a calling of which he has recorded his opinion with something like the courage of Xenophanes. He seems also to have essayed painting; but at fiveandtwenty he brought out his first play, the Peliodes, and thenceforth he was a tragic poet. At thirty-nine he gained the first prize, and in his career of about fifty years he gained it only five times in all [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“Throughout life he had to compete with Sophocles, and with other poets who represented tragedy of the type consecrated by tradition. The hostile criticism of Aristophanes was witty; and, moreover, it was true, granting the premise from which Aristophanes starts, that the tragedy of Aeschylus and Sophocles is the only right model. Its unfairness, often extreme, consists in ignoring the changing conditions of public feeling and taste...The infidelity of two wives in succession is alleged to explain the poet's tone in reference to the majority of their sex, and to complete the picture of an uneasy private life. He appears to have been repelled by the Athenian democracy, as it tended to become less the rule of the people than of the mob. Thoroughly the son of his day in intellectual matters, he shrank from the coarser aspects of its political and social life. His best word is for the small farmer, who does not often come to town, or soil his rustic honesty by contact with the crowd of the marketplace.”

“About 409 B.C. Euripides left Athens for Pella, on the invitation of King Archelaus, to the Macedonian court, where Greeks of distinction were always welcome. In his “Archelaus” Euripides celebrated that legendary son of Temenus, and head of the Temenid dynasty, who had founded Aegae; and in one of the meagre fragments he evidently alludes to the beneficent energy of his royal host in opening up the wild land of the North. It was at Pella, too, that Euripides composed or completed, and perhaps produced, the Bacchae. Jealous courtiers, we are told, contrived to have him attacked and killed by savage dogs.

Plays by Euripides

WEB MIT Classics Archive: Euripides classics.mit.edu

“2ND 11th Britannica: Euripides”Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece: sourcebooks.fordham.edu

“Alcestis” translated by C. A. E. Luschnig Diotima Diotima

“Andromache

“Bacchae” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“The Bacchae” Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece: sourcebooks.fordham.edu won trilogy competition, posthumously (405 B.C.)

“The Cyclops”

“Electra” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Hecuba”

“Helen”, a modern actable translation by Andrew Wilson, Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Herakles” (Hercules Furens) Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Herakleidae” (Children of Herkales) Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Hippolytus” Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece: sourcebooks.fordham.edu won trilogy competition in 428 B.C.).

“Hippolytus” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Ion” translated by C. A. E. Luschnig” Diotima Diotima

“Iphigenia” at Aulis won trilogy competition, posthumously (405 B.C.)

“Iphigenia In Tauris”

“Medea”, translated by C. A. E. Luschnig Diotima Diotima ”

"Medea” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

See 2ND Study Guide” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Orestes” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

“Orestes”, a modern actable translation by Andrew Wilson Classics Pages users.globalnet.co.uk

“The Phoenissae”, a modern actable translation by Andrew Wilson at Classics Pages users.globalnet.co.uk

“Rhesus”

“The Suppliants”

“Trojan Women”, translated by C. A. E. Luschnig Diotima Diotima

“Women of Troy” Internet Archive Web.archive.org

Features of Euripides’s Plays

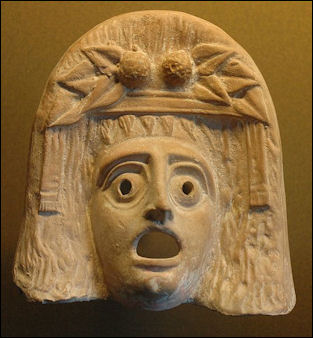

Dionysos mask Euripides had even more characters than Sophocles and focused on more human issues. He won less drama prizes than Sophocles and Aeschylus in part because his works were so emotional and disturbing. He invented a pulley and crane system that lowered and raised the gods in and out of the action. Once the crane was used to portray Socrates as being so lost in thought he was floating in the air.

Euripides wrote “The Women of Troy” , “Hippolytus” , “Iphigenia ay Aulis” , “The Bachae, Medea “ and “Hecuba” . One of the surprising things about them is how relevant they remain in their commentary on war and the human condition even though they were written more than 2,400 years ago. Nearly all of his works were written during the tragic 27-year-long Peloponnesian War and themes of many his plays deal with tragic lessons he learned from the conflict.

The Times of London theater critic Benedict Nightingale wrote: “Want to know about the limitations of reason as they’re being painfully demonstrated by nationalist demagogs, feral children, crazed cults, suicide bombers and assorted other fanatics? Try... “The Bachae” ...When Euripides writes of war, usually taking Troy as a paradigm, his scepticism, scorn for politicians and horrified mistrust of the human animal reality hits home...”The Trojan Women” , a long howl of grief...may be the greatest of all anti-war plays.”

Many of Euripedes works feature scheming and cruel women. Medea kills her husbands and their children to avenge an infidelity. Hecuba blinds a king and murders his children to avenge the death of her own child.

Dionysius in the Bacchae by Euripides

Euripides wrote in “The Bacchae,” 677-775: The Messenger said: “The herds of grazing cattle were just climbing up the hill, at the time when the sun sends forth its rays, warming the earth. I saw three companies of dancing women, one of which Autonoe led, the second your mother Agave, and the third Ino. All were asleep, their bodies relaxed, some resting their backs against pine foliage, others laying their heads at random on the oak leaves, modestly, not as you say drunk with the goblet and the sound of the flute, hunting out Aphrodite through the woods in solitude. [Source: Euripides. “The Tragedies of Euripides,” translated by T. A. Buckley. Bacchae. London. Henry G. Bohn. 1850.

“Your mother raised a cry, standing up in the midst of the Bacchae, to wake their bodies from sleep, when she heard the lowing of the horned cattle. And they, casting off refreshing sleep from their eyes, sprang upright, a marvel of orderliness to behold, old, young, and still unmarried virgins. First they let their hair loose over their shoulders, and secured their fawn-skins, as many of them as had released the fastenings of their knots, girding the dappled hides with serpents licking their jaws. And some, holding in their arms a gazelle or wild wolf-pup, gave them white milk, as many as had abandoned their new-born infants and had their breasts still swollen. They put on garlands of ivy, and oak, and flowering yew. One took her thyrsos and struck it against a rock, from which a dewy stream of water sprang forth. Another let her thyrsos strike the ground, and there the god sent forth a fountain of wine. All who desired the white drink scratched the earth with the tips of their fingers and obtained streams of milk; and a sweet flow of honey dripped from their ivy thyrsoi; so that, had you been present and seen this, you would have approached with prayers the god whom you now blame.

“We herdsmen and shepherds gathered in order to debate with one another concerning what strange and amazing things they were doing. Some one, a wanderer about the city and practised in speaking, said to us all: “You who inhabit the holy plains of the mountains, do you wish to hunt Pentheus' mother Agave out from the Bacchic revelry and do the king a favor?” We thought he spoke well, and lay down in ambush, hiding ourselves in the foliage of bushes. They, at the appointed hour, began to wave the thyrsos in their revelries, calling on Iacchus, the son of Zeus, Bromius, with united voice. The whole mountain revelled along with them and the beasts, and nothing was unmoved by their running.

“Agave happened to be leaping near me, and I sprang forth, wanting to snatch her, abandoning the ambush where I had hidden myself. But she cried out: “O my fleet hounds, we are hunted by these men; but follow me! follow armed with your thyrsoi in your hands!” We fled and escaped from being torn apart by the Bacchae, but they, with unarmed hands, sprang on the heifers browsing the grass. and you might see one rending asunder a fatted lowing calf, while others tore apart cows. You might see ribs or cloven hooves tossed here and there; caught in the trees they dripped, dabbled in gore. Bulls who before were fierce, and showed their fury with their horns, stumbled to the ground, dragged down by countless young hands. The garment of flesh was torn apart faster then you could blink your royal eyes. And like birds raised in their course, they proceeded along the level plains, which by the streams of the Asopus produce the bountiful Theban crop. And falling like soldiers upon Hysiae and Erythrae, towns situated below the rock of Kithairon, they turned everything upside down. They were snatching children from their homes; and whatever they put on their shoulders, whether bronze or iron, was not held on by bonds, nor did it fall to the ground. They carried fire on their locks, but it did not burn them. Some people in rage took up arms, being plundered by the Bacchae, and the sight of this was terrible to behold, lord. For their pointed spears drew no blood, but the women, hurling the thyrsoi from their hands, kept wounding them and turned them to flight—women did this to men, not without the help of some god. And they returned where they had come from, to the very fountains which the god had sent forth for them, and washed off the blood, and snakes cleaned the drops from the women's cheeks with their tongues.

“Receive this god then, whoever he is, into this city, master. For he is great in other respects, and they say this too of him, as I hear, that he gives to mortals the vine that puts an end to grief. Without wine there is no longer Aphrodite or any other pleasant thing for men. I fear to speak freely to the king, but I will speak nevertheless: Dionysus is inferior to none of the gods.”

Pentheus said: “Already like fire does this insolence of the Bacchae blaze up, a great reproach for the Hellenes. But we must not hesitate. Go to the Electran gates, bid all the shield-bearers and riders of swift-footed horses to assemble, as well as all who brandish the light shield and pluck bowstrings with their hands, so that we can make an assault against the Bacchae. For it is indeed too much if we suffer what we are suffering at the hands of women.”

Dionysus said: “Pentheus, though you hear my words, you obey not at all. Though I suffer ill at your hands, still I say that it is not right for you to raise arms against a god, but to remain calm. Bromius will not allow you to remove the Bacchae from the joyful mountains.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024