Home | Category: Art and Architecture / Literature and Drama

THEATER IN ANCIENT GREECE

There are 150 ancient theaters scattered around Greece and other places that date the ancient Greek period in Asia Minor (Turkey), Italy and around the Black Sea. Most have curved rows of concentric seats. In back of the orchestra was a hall-like building with changing rooms and support for the scenery. The fact that every Greek city of any size had a theater and sometimes more than one (Attica had several) is an indication of their importance to the community.

The theater offered an experience which brought together elements of myth, ritual, religion, dance, music and literature. It provided a forum for the exchange of ideas, an opportunity to escape from the sometimes harsh realities of everyday life and an occasion to see and be seen. It also had some of the hallmarks of an endurance contest since someone who attended a full festival of plays, and many did, listened to perhaps 20,000 lines of poetry while seated on hard wooden or stone benches. [Source: Canadian Museum of History

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Our interest in the theater connects us intimately with the ancient Greeks and Romans.Nearly every Greek and Roman city of note had an open-air theater, the seats arranged in tiers with a lovely view of the surrounding landscape. Here the Greeks sat and watched the plays first of Aeschylus, Sophokles, Euripides, and Aristophanes, and of Menander and the later playwrights.” [Source: Colette Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org]

Greek drama, both tragedy and comedy, grew of out of Dionysiac festivals, which could be quite wild. One consequence of theatrical performances held only at certain festive seasons of the year was that the structure of the theaters, and especially the place for the spectators, had to be quite large. As performances only took place a few times in the year, and not only the whole population of the town and neighbourhood, but even many strangers from a distance, collected together for them, the space for the audience had to be so large that many thousands, even tens of thousands, might have room there, and it must also be built in such a way that the performance could be conveniently seen from every place. These remarks refer in particular to Athens, with whose theatrical arrangements we are best acquainted, and which, moreover, was the model for most of the others. In the first place, it was impossible to have a covered space; covered theaters — concert-hall, as they were called — were destined, not for dramatic, but for musical performances; secondly, the performances took place by daylight, in consequence of which much of the illusion was lost. Again, the great size of the structure and the considerable distance of most of the seats from the actors necessitated certain peculiarities in the costume of these latter which we must discuss later on. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DRAMA IN ANCIENT GREECE: ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, TYPES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK THEATER PERFORMANCES: CONTESTS, ACTORS, MASKS, COSTUMES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDIES: PLOTS, TYPES, STRUCTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

GREAT ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY PLAYWRIGHTS: AESCHYLUS, SOPHOCLES AND EURIPIDES europe.factsanddetails.com

ARISTOPHANES AND ANCIENT GREEK COMEDIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Greek and Roman Stage” by David Taylor (1999) Amazon.com;

“Theatre and Playhouse: An Illustrated Survey of Theatre Buildings from Ancient Greece to the Present Day” by Richard Leacroft and Helen Leacroft (1985) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Greek Theater” by Mary Louise Hart (2010) Amazon.com;

“A Short Introduction to the Ancient Greek Theater” by Graham Ley Amazon.com;

“Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily” by Kathryn G. Bosher, Edith Hall, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre” by Marianne McDonald and Michael Walton (2011) Amazon.com;

“Theater of the People: Spectators and Society in Ancient Athens”

by David Kawalko Roselli (2011) Amazon.com;

“Costume in Greek Tragedy” by Rosie Wyles (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies” (Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents) by Peter Wilson (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Guide to Ancient Greek Drama (Blackwell) by Ian C. Storey and Arlene Allan (2013) Amazon.com;

“Greek Architecture” (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art)

by A. W. Lawrence (1996) Amazon.com;

“Greek and Roman Architecture” Gene Waddell (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture (Oxford Handbooks)

by Clemente Marconi (2018) Amazon.com;

Origin of Ancient Greek Theaters

Marco Merola wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Going to the theater was an essential part of ancient Greek civic and religious life. Plays such as the tragedies of Aeschylus and Euripides, the comedies of Aristophanes and Menander, and likely numerous other works that have not survived, were regularly staged at religious festivals. Masked actors and a chorus whose role was to comment on the play’s action in song, dance, and verse entertained festivalgoers and paid honor to the gods. “Since the very beginning of Greek civilization, a theater was always a religious building housed in a sanctuary,” says archaeologist Luigi Maria Caliò of the University of Catania. “In the Greek world, everything was related to holiness, and theaters were built in sacred areas.” [Source: Marco Merola, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019]

“At first, theaters were likely just open areas or hillsides with no cavea, or tiered seating area. From about the sixth to the fourth centuries B.C., says Caliò, Greek theaters were built of wood. Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus and Electra, for example, were performed in wooden theaters. Beginning in the fourth century B.C., theaters were often built in stone. “When theaters were monumentalized, they became a crucial part of cities around the Greek world,” Caliò says. Though nearly all traces of the wooden structures have been lost, remains of ancient Greek stone theaters still stand from Italy to the Black Sea, at sites such as Epidaurus in the Greek Peloponnese, the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, and Taormina in Sicily. As one of the most important cities in the ancient Mediterranean during the classical era and home to one of its grandest sanctuaries, Akragas (now Agrigento), on Sicily’s southern coast, must have had a theater as well. But no ancient sources mention one there and, until recently, no archaeological evidence of such a structure had ever been found.

The memory of the origin of the drama from choruses, to which in the course of time was added dramatic action, was preserved in a separation between the performers who presented the action and the chorus who only accompanied it — a separation which only gradually disappeared at a time when means were insufficient for defraying the considerable expenses of equipping a chorus. This distinction between actors and chorus was not only observed in the composition of the drama, but also in locality; the chorus, who not only sang, but also danced and marched, required a very large space for their evolutions, while the actors, whose number was very small, could do with less. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Ancient Greek Theaters

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The Greek theater consisted essentially of the orchestra, the flat dancing floor of the chorus, and the theatron, the actual structure of the theater building. Since theaters in antiquity were frequently modified and rebuilt, the surviving remains offer little clear evidence of the nature of the theatrical space available to the Classical dramatists in the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. There is no physical evidence for a circular orchestra earlier than that of the great theater at Epidauros dated to around 330 B.C.” [Source: Colette Hemingway, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org]

“Most likely, the audience in fifth-century B.C. Athens was seated close to the stage in a rectilinear arrangement, such as appears at the well-preserved theater at Thorikos in Attica. During this early period in Greek drama, the stage and most probably the skene (stage building) were made of wood. Vase paintings depicting Greek comedy from the late fifth and early fourth centuries B.C. suggest that the stage stood about a meter high with a flight of steps in the center. The actors entered from either side and from a central door in the skene, which also housed the ekkyklema, a wheeled platform with sets of scenes. A mechane, or crane, located at the right end of the stage, was used to hoist gods and heroes through the air onto the stage. Greek dramatists surely made the most of the extreme contrasts between the gods up high and the actors on stage, and between the dark interior of the stage building and the bright daylight.” \^/

At the 8000-seat marble amphitheater in Aphrodisias in Asia Minor, audiences watched masked and robed actors perform dramas about conspiring slaves and two-timing wives. When the show was over the audience was discouraged out of a gate called the vomitorium .

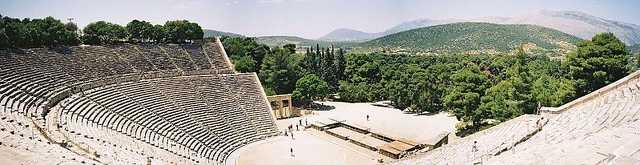

The Epidaurus Theater in Epidaurus (70 kilometers south of Corinth) is the most famous and best preserved ancient amphitheater theater in Greece. Built into a hillside surrounded by trees in the 4th century B.C., the theater has a circular stage. The acoustics are so good it is said an actor's whisper can be heard in the back row — a tribute to the the theater’s famous architect Polykleitos, the Younger. Plays are still regularly performed there. Its fifty-five rows of seats could accommodate up to 12,000 people, considerably more than can squeeze into an average city theater which, typically, has seating for 5000 people. |

How is it possible for music and voices to be heard with such clarity in the back rows? Limestone seats form an acoustics filler that hushes low-frequency background noises such as the murmur of the crowd and reflects high-frequency noises of the performers on stage off the seats and back towards the seated audience members. The theater is also very steeply sloped (30 to 34 degrees). This is creates a shorter path for direct sound with few interferences in that direct path. [Source: MCT, Georgia Institute of Technology]

Early Greek Theaters

To accommodate large crowds at festivals, open theaters were built in the 5th century B.C. The first Greek theaters were probably nothing more than wooden benches placed around the outside of an agora where dramas were acted out. Greece and Asia Minor were blessed with a hilly landscape and the Greek theaters that replaced the makeshift market stages were usually carved into the sides of hills.

In the fourth century B.C. cities began to build stone theaters. In fact one of the most characteristic buildings found in any ancient Greek city of any importance was a quality theater. Audiences in Athens who had attended presentations by the masters of the Greek stage- Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripides- had been seated on wooden benches lining the south slope of the Acropolis. Their descendants had a better environment. The typical Greek theater was built into the slope of a hillside which provided support for the curving banks of stone seats that faced the stage. Most patrons brought their own seat cushions to these open air structures since watching plays during a festival period was somewhat of an endurance contest. [Source: Canadian Museum of History |]

At first wooden benches were set up, but later they were replaced by stone or marble seats. The first theaters had a circular orchestra for singers and dancers. This followed the tradition of the early Dionysus festivals when the merrymakers danced around a maypole, altar or image of a god. Theaters built later on had a “ vomitorium”, so named because it discouraged the audience after a performance. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]**

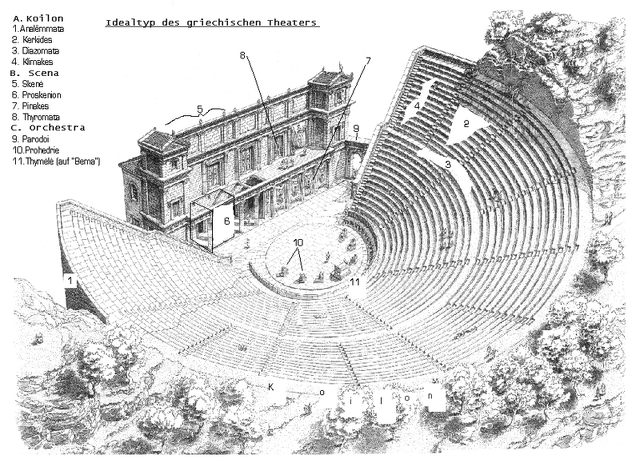

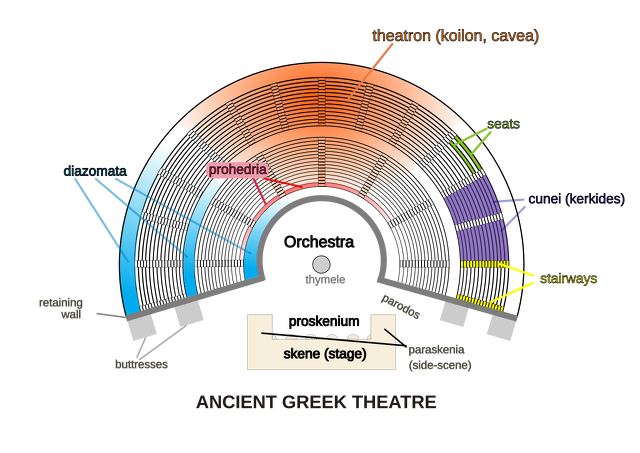

Structure of an Ancient Greek Theater

While the modern theater consists of only two parts, the stage with its accessories and an auditorium, the Greek theater consisted of three parts; besides the auditorium and the structure of the stage, there was between the two a space for the chorus known as orchestra. In considering the arrangement of the buildings, we derive assistance from the descriptions of the ancients, as well as the still existing remains of Greek theaters. One image represents the ground plan of the ruins of the great theater of Dionysus at the Acropolis in Athens, though we must remember that this structure, built originally in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., had experienced considerable changes in the Roman period. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

We may regard the orchestra as the center of the whole structure. This was originally only a level dancing place, and its shape was usually an incomplete circle, since part was cut off by the stage, which extended at right angles along the orchestra. Opposite to this the circumference of the orchestra was surrounded in concentric lines by the raised seats of the auditorium, the theater in the true sense of the word. There is no fixed standard for the shape of the orchestra and the corresponding auditorium; sometimes it is a semicircle with the circumference extended a little way on both sides, sometimes it is lengthened by a tangent, or some other line at right angles to the circle.

In the great theater of Dionysus in Athens the orchestra was originally a perfect circle; a complete semicircle, which is common in the Roman theaters, was very unusual in those of Greece. Here, as in the structures used for games, such as the Stadia and Hippodromes, the Greeks tried as far as possible to utilise the natural conditions of the ground for their theaters. If possible, therefore, they placed the auditorium on some natural elevation; thus, the great theater of Dionysus extends up the southern slope of the Acropolis; and if there was no such elevation they often supplied it by artificial mounds of earth, differing thus from the custom of the Romans, who, in consequence of the greater development of their architectural knowledge, were able to build a theater on an open space, and to support the auditorium by strong sub-structures. The Greek mode of building had the advantage of greater cheapness and security, and, if the nature of the ground permitted, also enabled them to make exits and entrances for the public besides those below. In the theater of Dionysus there were side approaches on the high ground also. The auditorium of the Greek theater was usually situated in some beautiful spot, from which the visitors to the theater, at any rate those on the higher ground, who were not hindered by the structure of the stage opposite, had an extensive view. Thus the theater of Syracuse had a glorious view over the harbour and town — in fact, nearly all the theaters in the neighbourhood of the sea are usually so built that the auditorium is open towards the sea, and the fresh breeze may refresh the public during the hot hours of the day.

The seats, according to the nature of the locality, were either hewn direct out of the rocky ground or based on artificial foundations. At Athens the spectators originally sat on the bare ground of the Acropolis slope or on wooden benches placed there; in the fourth century stone steps were made there.

At Syracuse, Sicyon, and other places, nearly the whole auditorium and the steps were hewn out of the rock; the ends or wings of the auditorium, which jutted out where the seats ended, close by the stage, had to be of specially massive construction. Sometimes, though more often in the Roman than the Greek theaters, the auditorium touched the side wings of the stage; but this was not a particularly convenient method, since a considerable number of the places along this stone wall had no view of the stage or, at any rate, only a very unsatisfactory one. Entrance was procured for the public by the great gates which led on the right and left between the auditorium and the stage, and which, when the spectators were assembled, also formed the entrances for the chorus (πάροδοι). When a theater was situated on elevated ground, there were also other approaches leading to the gangways of the upper storeys; probably these were only used for emptying the theater, and not for admission, since on entering the spectators had to pay for their admission, or else present their tickets, and therefore the number of entrances was probably limited with a view to simplifying the control.

In those theaters where the seats extended as far as the stage, the approaches which were below the seats had to be covered over, but, as a rule, we must suppose that they were uncovered. The seats were arranged in such a manner that the steps, which rose from the orchestra to the top of the theater, were also used as seats; people sat on the actual stone, unless, as sometimes happened, they brought cushions with them, or had these carried by slaves. There were a number of places in the lower rows distinguished from the others by seats of honour, made also of stone, usually of costly marble; some of these seats, dating, however, from the Roman period, have been found in the theater of Dionysus. The usual height of the steps was from about 16 to 19 inches, and the depth from 24 to 28. There was no division of seats, and though probably care was taken that too many persons should not be crowded together, yet there were no lines drawn to mark out the appointed places. There was a very convenient and at the same time simple arrangement for preventing the feet of those who sat on a higher row from inconveniencing those in front. The depth of the seat was often sufficient to prevent contact, but, besides that, it was the custom to hollow out that part of the step where the spectators would put their feet. Some of the steps, in fact, have three distinct surfaces: the nearest of these to the row above was hollowed out for the feet; then came a gangway for those who wished to move to or from their places, who could thus pass along without incommoding those who were seated; and the third surface was that on which the next row below were seated. There were, as a rule, no backs to the seats, but in places where there was a wider gangway, and thus one row of spectators did not come into immediate contact with the next, they were sometimes introduced and made of one piece with the seat.

Theater in Athens

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece”, Book I: Attica (A.D. 160): “In the theater the Athenians have portrait statues of poets, both tragic and comic, but they are mostly of undistinguished persons. With the exception of Menander no poet of comedy represented here won a reputation, but tragedy has two illustrious representatives, Euripides and Sophocles. There is a legend that after the death of Sophocles the Lacedaemonians invaded Attica, and their commander saw in a vision Dionysus, who bade him honor, with all the customary honors of the dead, the new Siren. He interpreted the dream as referring to Sophocles and his poetry, and down to the present day men are wont to liken to a Siren whatever is charming in both poetry and prose. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“The likeness of Aeschylus is, I think, much later than his death and than the painting which depicts the action at Marathon Aeschylus himself said that when a youth he slept while watching grapes in a field, and that Dionysus appeared and bade him write tragedy. When day came, in obedience to the vision, he made an attempt and hereafter found composing quite easy. Such were his words. On the South wall, as it is called, of the Acropolis, which faces the theater, there is dedicated a gilded head of Medusa the Gorgon, and round it is wrought an aegis. At the top of the theater is a cave in the rocks under the Acropolis. This also has a tripod over it, wherein are Apollo and Artemis slaying the children of Niobe. This Niobe I myself saw when I had gone up to Mount Sipylus. When you are near it is a beetling crag, with not the slightest resemblance to a woman, mourning or otherwise; but if you go further away you will think you see a woman in tears, with head bowed down.”

Auditorium in an Ancient Greek Theater

In larger theaters the auditorium was almost always divided into several storeys by gangways. These gangways ran round the auditorium concentrically with the seats, and their object was to facilitate the circulation of the public; they were therefore of considerable breadth, and sometimes two such gangways were put close to each other, one higher and one lower, so that the public could circulate easily on them without pushing each other. The separate seats were everywhere connected by steps. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Although the arrangement of the whole auditorium with its raised seats was that of a circus, yet the seats were far too high to be used as steps also, and these had to be specially constructed. They were of two kinds; small steps in the direction of the seats, the object of which was to enable people to mount from one seat to the next, and the principal staircases, which intersected the seats through their whole extent from top to bottom, and formed, as it were, radii of the circle represented by the auditorium. The number of these staircases was larger or smaller as occasion required; sometimes the number was doubled at the top, where the distances increased, by introducing a third staircase between each pair; sometimes the staircases which began below did not continue at the top, but there was a change in the radii. It was most common, however, for these staircases to intersect the whole theater right up to the highest seats, and thus to divide the whole auditorium into a number of wedge-shaped divisions, which, in fact, received the designation of wedges (κερκίδες). Sometimes these wedges had special names, being called after statues which were placed there, as, for instance, in the theater at Syracuse, and these designations facilitated the finding of places. As a rule, the steps were so arranged that there were two to every seat, thus each step was half the height of the seat.

In later times the upper seats led to open arcades; when the ground permitted it, the Romans often laid out walks and gardens on the elevation of the theater, where the spectators might refresh themselves during intervals; below, near the orchestra, the auditorium was cut off by a wall, which must be so low that the spectators on the first seat could conveniently see the stage, which was raised a good bit above the orchestra. Sometimes the first gangway for the circulation of the public was placed behind this wall, which was bounded by a low breastwork; when this was the case, steps of the first-mentioned kind led up sideways to the orchestra.

The size of the auditorium varied greatly. If our measurements of ruined theaters are correct, the theater at Ephesus was the largest of all; Falkener has calculated that it could contain 56,700 people. The largest theater in Europe was that of Megalopolis, which was calculated to have 44,000 seats, and the theater of Dionysus 30,000. These calculations are, however, very uncertain, since we do not know how many feet were allotted to each person, and a variation of half a foot would make a very considerable difference.

Orchestra in an Ancient Greek Theater

The most important question connected with the orchestra deals with the Thymele, often alluded to by ancient writers. It was formerly assumed that this represented the ancient altar of Dionysus, round which the choruses originally danced, and that it was situated in the center of the orchestra, while the chorus grouped around it, and that the leader of the chorus stood near the Thymele or on its steps, and the officials of the theater also took their stand there. A structure resembling an altar with steps is placed in the middle of the orchestra. But this interpretation of the Thymele has proved untenable, and though it is not possible to decide this question with any certainty, yet, among the various hypotheses, that of Wieseler seems the most probable — such as that the Thymele was a wooden scaffolding constructed in the orchestra, on which the chorus performed its dances. The main object of this scaffolding, or podium, was not so much to place the chorus on higher ground as to facilitate their games and dancing, because it was easier to move and dance on the elastic floor of a wooden scaffolding than, as formerly, in the dusty orchestra, which, in fact, from this circumstance received the name “dust-place”, or even on the stone pavement which seems to have been afterwards laid down in the orchestra.

We do not know whether there were steps leading from the floor of the orchestra to this scaffolding, and, in fact, we cannot even determine its height. The size of the podium must have been considerable, since it must have supplied sufficient space for a large chorus. Besides its members, the number of which in cyclic choruses often amounted to fifty, the musicians who accompanied took their place there, and, apparently, even the constables, who superintended the theater; for, strange as it may seem to us that the officials whose duty it was to keep order among the public should be placed in so prominent a position at the side of the chorus, yet the proofs in favor of this arrangement seem decisive. The usual entrances to the orchestra for the chorus were the same as those used by the public; here, as in the arrangements on the stage, the rule was that the entrance on the right hand of the spectators indicated approach from the neighbourhood, from the town or harbour, and the left arrival from a distance.

Stage in an Ancient Greek Theater

The stage in the early days of the theater was not much more than a mere wooden scaffolding, on which the actors appeared, while the chorus performed its dances in the orchestra below. There was a tent on the side turned away from the orchestra which served as a place of waiting for the actors when they had nothing to do on the stage, and it was this tent (σκνή) which gave its name to the stage, although even afterwards distinction was made between the actual stage and the structures connected with it. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The real stage was an oblong surface, raised from ten to twelve feet above the orchestra; it was called the proscenium, and sometimes the speaking-place. The lower front wall was decorated in the Roman period with architectural designs, reliefs, or painting; we do not know whether this was also the case in the Greek theater, as Strack has assumed in his reconstruction, but it is very probable that the front scene, which was turned to the spectators was not left quite bare. In Strack’s view there were also steps leading from the orchestra to the speaking-place. We cannot tell whether these were regularly placed in the theaters. Still, steps between the orchestra and stage were indispensable in those plays in which (as, for instance, in “Philoctetes”) the chorus leaves the orchestra and ascends to the stage; but it is quite possible that there were special wooden steps used for this purpose, which were taken away again when this connection was not required. The existence of these movable steps is especially mentioned in ancient writers.

Connected with this proscenium were the buildings belonging to the stage; these usually formed a structure several storeys in height, which enclosed the stage on three sides in the plan of the theater of Dionysus. Investigations have shown that the stage of the theater of Dionysus, constructed by the orator Lycurgus, had originally no fixed proscenium, but that a fresh wooden stage was constructed on every occasion. In later times they cut off a piece of the two side wings and fixed scenery between them. Several doors led from the tent to the stage; as a rule, there were three in the background, of which the middle one was the entrance of the chief actor, called “Protagonist,” and was supposed to lead either from a royal palace, or a dwelling, or a cave, according to the nature of the play; the door on the right was for the second actor, the one on the left had no special significance.

We must not, however, regard these statements as universal. Probably there were usually three entrances to the stage, though in the theater of Dionysus there is only a single door; but as the front was usually covered by some decoration, these entrances were not directly used, but the actors came through them into the narrow space between the wall of the stage and the decorations, and thence through the doors in the decorations on to the stage. The scenery of the background varied according to the nature of the action, and sometimes required several doors or entrances; sometimes there may have been no door at all, since the actors also had at their disposal the entrances by the side wings. These statements, therefore, only refer to certain plays, especially those tragedies in which the chief personage is a king; in this case, probably, the middle door was the one supposed to lead to the royal palace, and used, therefore, only by the protagonist, although we must not on that account suppose that he always came and went through this door, since the nature of the plays would of itself forbid this. Very often, too, a king appeared in the play whose part was an unimportant one, not given to the protagonist, and then, of course, the rule above quoted could not be observed.

The side wings were used for the actors to wait in, and it is very probable that the chorus also before making their appearance, and during the time when they were not present in the orchestra, retired thither, and that there were passages leading thence to the side entrances. There were also doors communicating with the stage, and these, like those in the orchestra, had their special significance; through the right-hand door came those actors who were supposed to come from the town, and through the left those who came from a distance, such as messengers, guests, friends returning home, etc.

Scene-Painting and Decorations in an Ancient Greek Theater

The decorations were only on the stage, the orchestra was left quite bare, and probably had not even any movable properties. It is pure fantasy to suppose that in some plays a connection was established between the stage and orchestra by making the whole represent a mountain with rocky caves, etc. The Greeks assumed a certain amount of illusion, but confined this to the stage; they did not trouble about the space in front, any more than we care to-day about the appearance of the orchestra in front of the opera. It was the scene represented on the stage that gave its significance to the orchestra; if a palace was represented, and the stage represented the place in front of it, then the orchestra became an open space, on which the people assembled; if the background was a temple, the orchestra was the sacred space immediately in front of it, and so on. Possibly the wall under the front of the stage was connected with the decoration, so that if the stage, for instance, represented a wild forest with a cave, the front of the scene was similarly decorated. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Scene-painting, in which Greek art first made an attempt at perspective drawing, had no such difficult and complicated tasks to accomplish in those times as in ours. The chief pieces of scenery were the background and the revolving pieces. The background of the proscenium had to cover the wall of the stage, and also indicate the place of the action, whether a square in front of a palace, or a street with private houses, or a forest, etc. We must not think of the great variety of scenery known to our modern stage; no doubt, too, they were content with very simple execution, merely hinting at the scene required. The background was probably suspended in a wooden scaffolding or frame, and placed immediately before the inner scene front on the floor of the stage. We do not know, however, how the decoration of the background was changed, for change of scene was sometimes necessary even in the ancient drama; perhaps they were in the habit in such cases of placing one of the scenes in front of another, so that, as at the present day, the front decoration had only to be moved, either by dropping it or by dividing it in two parts drawn to the side (for in the absence of rods they could not draw them up), and thus the second scene became visible behind.

The second kind of decoration, which took the place of our movable scenes, were the revolving pieces. These were two contrivances shaped like a three-sided prism, placed on either side of the stage at a little distance from the side-wings; their axis was attached to the wooden floor of the stage, and round this they moved. Each of them had three surfaces for decoration, so that, by turning them round, three different scenes could be represented, and this was doubtless enough for any play, for in the pieces which have come down to us there is only change of scene in two, the “Eumenides” of Aeschylus, and the “Ajax” of Sophocles, and in both these tragedies there is only one change. These revolving pieces must also have had a little store of decorations, for it was very easy to cover them with a change of picture, as they appear to have been simple stands. The theory that the ancient stage had altogether only three scenes for these stands — such as one for tragedy, one for comedy, and one for the satyric drama, is undoubtedly mistaken.

The Greek stage had no other scenery than that for the background and the revolving pieces; there must have been some movable properties, such as benches, altars, tombs, etc., which are indicated by the contents of many plays preserved to us. It is very doubtful whether the Greek theater resembled the Roman in the use of a curtain, which, instead of drawing up, sank down into the ground when the play opened; there is no absolute proof that this was the case. The modern prompter’s box was unknown, and it is evident that they did not make use of a prompter.

Stage Accessories and Machines in an Ancient Greek Theater

Using an ekkyklema: a wheeled platform rolled out on the stage in an ancient Greek theater to bring interior scenes out into the sight of the audience

The machinery of the ancient stage seems to have been very complicated. Of most of the theatrical machines we know only the names, and can form but a very insufficient conception of them. A contrivance in very frequent use was the “rolling-out machine”, which, according to the statements of ancient writers, was used to show the spectators proceedings in the interior of a house — as we should say, “behind the scenes;” for in the Greek drama the scene was never laid inside a room, but everything went on in the open air. Our authorities do not, however, enable us to form any clear conception of this contrivance; probably the background opened out in some way, and the person or group which was to be seen on the machine was rolled out on a wooden scaffolding moving on rollers or wheels, which must, of course, have been decorated in some way; in some cases it may have been unnecessary to open out the background, and sufficient for the machine to be pushed in through one of the three doors. There was a similar contrivance for rolling out persons who were to be shown in the upper storey of a house at a corresponding height above the stage, as we see from the “Acharnians” of Aristophanes, where Euripides appears in this manner on a sort of balcony in the upper storey. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Another contrivance bore the special name of “machine”, and was the origin of the expression Deus ex machina, used when a god, descending from Olympus, violently cut the knot of the action; this was used for suspending in the air gods, heroes, or mortals, but especially those persons who had to appear above as though flying. We cannot tell where this machine was attached, and how it was worked; there seems to have been a contrivance of this kind on either side of the stage, above the side entrances, near the side pieces, and the one on the left was used by gods, while that on the right was used for other purposes. The machine itself must usually have been kept in some upper storey of the stage structure. It must have been a somewhat dangerous means of transit; the actors who had to perform this aerial journey were usually bound fast with ropes or girths, and in the “Peace” of Aristophanes Trygaeus, when mounting on his aerial horse, the dungbeetle, which must have been a similar flying machine, implores the manager of the machinery, who has to superintend all these arrangements, to be very careful that he does not come to grief. The “gods’ speaking-place” appears to have been a scaffolding above the chief entrance in the background, on which the gods appeared, probably surrounded by clouds; it differed from the “machine” in showing the gods peacefully throned above, instead of bringing the Olympian deities down to earth. Connected with the “machine” was the “crane” , a crane-like machine let down from above, which was used when human beings were to be lifted up from the stage; as, for instance, when Eos carried away the corpse of Memnon through the air.

They also had machines for producing thunder and lightning. We do not know how the lightning was made, and it is difficult to imagine that it could have been produced with any great result in broad daylight. The thunder was caused by rolling bladders full of little stones to and fro on brass plates in the hollow space under the stage. In this hollow space were also probably the “steps of Charon,” a contrivance for bringing the spirits of the dead on to the stage. Nothing certain is known concerning these steps, but it is very probable that they were managed after the fashion of our trap-doors, for undoubtedly the floor of the stage covered a hollow space, and thus a contrivance of this kind was very easily produced.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024