Home | Category: Culture and Sports

ANCIENT GREEK CULTURE

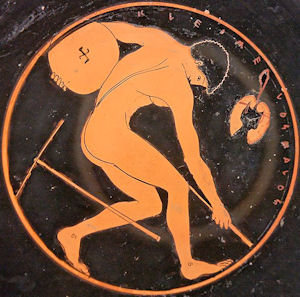

Greek vase painting of an athlete The Greeks found aesthetics in everything. Ancient Greece was one of the first civilizations to widely use writing as a form of literary and personal expression. For the Mesopotamians and Egyptians it was used mainly to make records and write down incantations for the dead. The Greeks, by contrast wrote dramas, histories and philosophical and scientific pieces. Even so most people were illiterate and writing was seen mainly as something that helped the memory and aided the spoken word. From what can be ascertained people read aloud rather than silently to themselves.

Greece reached its zenith during the Golden Age of Athens (457 B.C. to 430 B.C.) when great temples were built in Athens and Olympia and they were decorated with wonderful sculptures and reliefs. Hellenistic arts imitated life realistically, especially in sculpture and literature.

The Muses were the goddesses of arts and sciences and the keepers of the Arts. The Greeks believed the Goddess of Memory (Mnemosyne) gave birth to all nine Muses and was the mother of the arts. The nine daughters of King Pierus once challenged the muses to a singing contest and lost. For their boldness the nine daughters were punished by being turned into magpies, birds capable of screeching out only one monotonous note. The nine Muses are: 1) Epic poetry (Calliope), 2) History (Clo), 3) Flute Playing (Euterpe), 4) Tragedy (Melpomene), 5) Dancing (Terposchore), 6) the Lyre (Erato), 7) Sacred Song (Polyhymnia), 8) Astronomy (Urania), and 9) Comedy (Thalia).

Myths, See Religion; Drama, See Theater

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture” by Sarah B. Pomeroy, Stanley M. Burstein, et al. (2004) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Aesthetics” (Blackwell) by Pierre Destrée, Penelope Murray Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: History, Culture, and Society” by Ian Morris and Barry B. Powell (2021) Amazon.com;

“Hellenistic Science and Culture in the Last Three Centuries” by George Sarton (1993) Amazon.com;

“Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction” by Benjamin W. Fortson IV Amazon.com;

“Greek Writing from Knossos to Homer: A Linguistic Interpretation of the Origin of the Greek Alphabet and the Continuity of Ancient Greek Literacy” by Roger D. Woodard (1997) Amazon.com;

“Athens, A Portrait of a City in Its Golden Age by Christian Meier” (Metropolitan Books, Henry Holy & Company, 1998) Amazom.com

“War, Democracy and Culture in Classical Athens” by David Pritchard (2010) Amazom.com

“The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education & Culture in Ancient Sparta” by Nigel M. Kennell (1995) Amazon.com;

“Archaic and Classical Greek Art” (Oxford History of Art) by Robin Osborne (1998) Amazon.com;

“Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art: Art and Thought in Ancient Greece”

by Ian Jenkins (2015) Amazon.com;

“Myth and Society in Ancient Greece” by Jean-Pierre Vernant and Janet Lloyd (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Dictionary of Classical Myth and Religion” by Simon Price and Emily Kearns (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook” by Emily Kearns (2010) Amazon.com;

Ancient Greek Intellectual Pursuits

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Throughout the Hellenistic period (323–31 B.C.), Athens remained the leading center for the study of philosophy, fostering several famous philosophical schools (1993.342). The first to be established in the first half of the fourth century B.C. were Plato's Academy, and Aristotle's Peripatos, a place for walking, built on the site of a grove sacred to Apollo Lykeios. In the second half of the fourth century B.C., Zeno of Citium (335–263 B.C.) established his Stoic school of philosophy, named for his teaching platform, the stoa, or arcade, in the Athenian Agora. Around the same time, Epikouros (341–270 B.C.) developed his philosophical school, the Kepos, named after the garden in Athens where he taught (11.90). The schools, as some of their names imply, were less buildings than collections of people sharing a similar philosophy of life (10.231.1). They were devoted to gaining and imparting knowledge. The Cynics were another philosophical group that had no meeting place. Rather, they roamed the streets and public places of Athens. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The two schools of thought that dominated Hellenistic philosophy were Stoicism, as introduced by Zeno of Citium, and the writings of Epikouros. Stoicism, which was also greatly enriched and modified by Zeno's successors, notably Chrysippos (ca. 280–207 B.C.), divided philosophy into logic, physics, and ethics. Epikouros, on the other hand, placed great emphasis on the individual and the attainment of happiness. The Athenian schools of philosophy were truly cosmopolitan institutions. Teachers and students from all over Greece and Rome came to study. In addition to philosophy, students engaged in rhetoric (the art of public speaking), mathematics, physics, botany, zoology, religion, music, politics, economics, and psychology. \^/

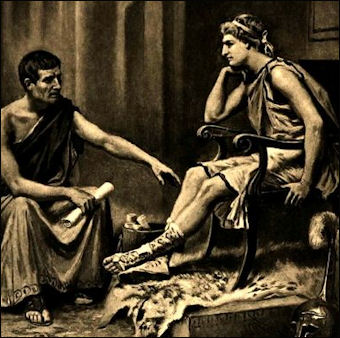

Aristotle tutoring Alexander the Great “Elsewhere in the Hellenistic world, rulers of the Macedonian court at Pella and the Seleucid dynasty at Antioch supported the pursuit of knowledge as benefactors of intellectuals. In many ways, this kind of patronage developed first at Alexandria, Egypt, where Ptolemaic kings created a renowned intellectual center during the early Hellenistic period. Prominent philosophers, writers, and other scholars studied at the Alexandrian Library and Mouseion, an institute of learning that is the root of the modern word museum. Here, scholars copied and codified earlier works, such as Homer's Iliad and Odyssey (09.182.50). They wrote commentaries, compilations, and even encyclopedias. They also enjoyed access to one another and, most likely, were fed and housed at the king's expense. In the latter part of the third century B.C., the Attalid kings of Pergamon emulated the Ptolemaic dynasts by building their own library, which attracted artists and intellectuals away from Athens and Alexandria to their royal court. \^/

“The Hellenistic period was a golden age of Greek poetry, whose practitioners easily measured up to the great lyric poets of the Greek Archaic and Classical periods (09.221.4). Literature also flourished. One writer, Kallimachos of Cyrene, is credited with more than 800 books! Although relatively little Hellenistic literature survives, much can be gleaned from Roman literature, which was significantly influenced by the Greek writers. Generally speaking, drama was less popular in the Hellenistic period than in Classical times, although Menander (344–292 B.C.), a comic writer from Athens, was a prolific exception. His plays embodied new ways of presenting and discussing the life of the individual and the family. \^/

“In the Hellenistic period, tremendous strides were made in scientific understanding. Early on, Euclid (ca. 325–250 B.C.) wrote a book of elementary mathematics that was to become the standard textbook for more than 2,000 years. The mathematician Apollonios of Perge (ca. 262–190 B.C.) established the canonical terminology and methodology for conic sections. And Archimedes of Syracuse (ca. 287–211 B.C.), whom many consider the greatest mathematician of antiquity, made important contributions to engineering, including wondrous machines that were used against the Romans at the siege of Syracuse in 212 B.C. Another Hellenistic inventor, Ktesibios of Alexandria (ca. 296–228 B.C.), was the first to devise hydraulic machines, most famous of which are his water clocks. \^/

“In the second half of the second century B.C., the astronomer Hipparchus (ca. 190–120 B.C.) transformed Greek mathematical astronomy from a descriptive to a predictive science. His work provided the foundation for Ptolemy of Alexandria's thirteen-volume systematic treatise on astronomy, which was published in the middle of the second century A.D.

Greek Versus Roman Culture

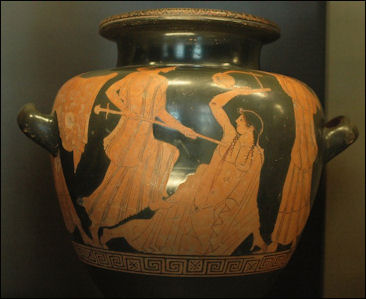

Muses in Pompeii Art from ancient Greece and Rome is often called classical art. This is a reference to the fact that the art was not only beautiful and of high quality but that it came from a Golden Age in the past and was passed down to us today. Greek art influenced Roman art and both of them were an inspiration for the Renaissance

The Greeks have been described as idealistic, imaginative and spiritual while the Romans were slighted for being too closely bound to the world they saw in front of them. The Greeks produced the Olympics and great works of art while the Romans devised gladiator contests and copied Greek art. In “Ode on a Grecian Urn” , John Keats wrote: "Beauty is truth, truth beauty, “that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

In the “Aeneid “ Virgil, a Roman, wrote:

“ The Greeks shape bronze statues so real they

they seem to breathe.

And craft cold marble until it almost

comes to life.

The Greeks compose great orations.

and measure

The heavens so well they can predict

the rising of the stars.

But you, Romans, remember your

great arts;

To govern the peoples with authority.

To establish peace under the rule of law.

To conquer the mighty, and show them

mercy once they are conquered.”

Greek Heroes, Sometimes Behaving Badly

Heros and heroism were central to Greek literature, art and religion. Karen Rosenberg wrote in the New York Times, “The ancient Greeks did not require perfection of their heroes, only greatness. They would certainly recognize some of our heroic figures (trapped miners, soldiers, quick-thinking pilots), but not our shock at the personal conduct of others (sports stars, politicians). Greek heroes misbehaved frequently, and when they did — Achilles dragging Hector’s body behind his chariot, Odysseus boasting to the Cyclops Polyphemus — it was a matter to be settled between the hero and the gods.[Source: Karen Rosenberg, New York Times, October 21, 2010]

This is one of the points made at the 2010 exhibition “Heroes, Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece” at the the Onassis Cultural Center in New York. Rosenberg wrote, “The exhibition begins with a parade of four figures — Odysseus, Achilles, Hercules and Helen — as seen on painted vessels and in sculpture. Later sections widen the focus to include athletes, soldiers and other local heroes who are now obscure.

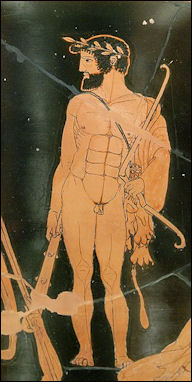

Hercules The shaggy, bearded Odysseus in a Roman bust looks like a humble fisherman, but a one-eyed head of Polyphemus nearby reminds you of Odysseus — harrowing escape from the Cyclops’s cave. Recalling the episode in further detail, a krater attributed to the Sappho Painter shows a grimacing Odysseus making his way to safety while strapped to the underbelly of a sheep.Not surprisingly, artists delighted in depicting some of Odysseus’ less fortunate crew members. The painting on a tall lekythos, or oil jug, from the National Archaeological Museum in Athens shows two men transforming into pigs under the spell of the sorceress Circe.

Cunning was Odysseus’ chief attribute, as Homer constantly reminds us. Achilles, meanwhile, was admired for his martial intelligence that, if unchecked, could result in vengeance of the ugliest variety. But the objects here show his softer side: his education by the centaur Chiron, his board-game sessions with Ajax and his eventual release of Hector’s brutalized body after pleas from Priam. Depicted on a huge amphora from the Toledo Museum of Art, that scene is one of the exhibition’s most intense. It shows an imperious Achilles reclining on a chaise above Hector’s bloodied corpse, as a supplicating Priam seems to reach forward for his son with every muscle in his body. Behind him Hermes gives a nudge to a servant bearing gifts — a reminder that the gods had the power to make or break heroes. Heroism as destiny is the subtext of several images of the young Achilles (and his parents, the mortal Peleus and the sea nymph Thetis). Many Greek heroes had one divine parent and were, in essence, groomed for greatness from birth.

The show’s main heroine is Helen, the bride of Menelaus and catalyst of the Trojan War. She’s a passive hero, a gorgeous liability. Or so it seems to modern-day viewers, seeing her passed from Menelaus to Paris and back again. Yet the ancient Greeks worshiped her, particularly the young women of Sparta, who made ritual offerings to Helen in the hope that she would bless them with fertile marriages.

The show’s final sections include many other examples of hero-cult activity, mainly small votives and large reliefs that were placed at tombs or shrines. Many of these heroes and their deeds, unlike those in the myths and epics, are unknown to us. Some were soldiers who died in battle, depicted in memoriam as idealized, beardless youths. (The inscription on one striking image of a warrior reads, “The boy is beautiful.”) Others were mere children. (In the show’s substantial catalog, the scholar John H. Oakley has a fascinating and unsettling essay on child-heroes in Greek art.)

Athletic competitions were also a form of hero worship, linked to Hercules and other strongmen. Horse racers, wrestlers and disc throwers populate the show’s final gallery, inviting comparisons with contemporary sports celebrities. That idea can be misleading; the Panhellenic Games, for instance, were as much a religious and musical festival as a sporting event.

Why did the Greeks pay so much attention to heroes, especially minor ones, when they already had an entire pantheon of gods? One reason is that heroes, in death, were believed to have godlike powers over the living — powers they could use for good or evil. They were ultimately mortal — a point underscored in the opening lines of the Iliad, in which “strong souls of heroes” are “hurled in their multitudes to the house of Hades” but fame gave them a kind of immortality. (As W. H. Auden wrote, “No hero is immortal till he dies.”)

Mary Beard and Christopher Jones on Greek Heroes

Orpheus's death In a review of Christopher P Jones’ book “New Heroes in Antiquity”, Mary Beard wrote in the New York Review of Books, “Modern heroism — as in “hero worship,” “culture hero,” “working class hero,” and so on — is not quite the same as the ancient version. The heroes that Jones discusses were divine or semi-divine figures, occupying part of that large grey area between “proper” Olympian gods and poor suffering, ordinary humanity. For the Greeks and Romans, “hero-worship” was not a metaphor. The grave of a hero would become a religious shrine (in Greek, heroon) and receive sacrifices and offerings from those who came, literally, to worship. [Source: , Mary Beard, New York Review of Books, March 3, 2010]

It is impossible to pin down exactly what the qualifications were for ancient heroic status. Like many ancient religious categories it was capacious and its boundaries conveniently vague (as a general rule, Greco-Roman polytheism tended to incorporate rather than exclude). For a start, anyone who fought in the Trojan War was a “hero” — for the ancient Greeks saw this as the great former age when all “mortals” were “heroes.” Some were even given their own shrines. Visitors to Sparta in the fifth century BCE would have been able to visit the Menelaion — an impressive sanctuary of King Menelaos and his errant wife Helen (also a “hero” on this definition — and worshipped in Sparta well into the Roman period, and probably for longer than Menelaos himself). There are some tremendous ancient images of this kind of hero in a stunning new exhibition, Heroes: Mortals and Myths in Ancient Greece, organized by the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, currently on show at the Frist Center in Nashville.

But Jones is more concerned with heroes who were created from the classical period of Greece on. He starts from the Spartan general Brasidas who died fighting the Athenians in the Peloponnesian War and was worshipped as a “hero” in the city where he had fallen, with sacrifices and annual games. He shows that it was probably “heroization” that Cicero had in mind when, four centuries later, he planned a “shrine” (Latin fanum), to be erected for his dead daughter, Tullia. And his last main example from pagan antiquity is Antinous — whose cult, as established by Hadrian, he sees very much in ancient “heroic” terms.

Book “New Heroes in Antiquity: From Achilles to Antinoos” by Christopher P. Jones (Harvard University Press, 2010)

Ancient Greek Literature

As a rule Greek literature and drama was meant to be read and heard aloud not to be read quietly from a book. Most classic works were recited by traveling bards or written for drama competitions. Reading wasn’t popular because reading from unrolled scroll was not an easy thing to do.

Myth and the Homeric epics infused everyday life. By examining literature and drama, historians have been able to draw great insights into everyday Greek life.

Translating Greek literature and poetry presents great difficulty because Greeks phrases tend to express things that the English language needs at least twice as many words to express. Literal translations of Greek are awkward and repetitive. The best translations are often the ones that have taken the most liberties. any Greek words have multiple meanings or meanings that are difficult to translate exactly.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK LITERATURE europe.factsanddetails.com ; Also See Philosophy Under Science and Philosophy

Theater and Drama in Ancient Greece

The Greeks are regarded as the inventors of drama. The Egyptians produced simple plays about the pharaoh’s birth at his crowning and plays about resurrection at the pharaoh’s funeral. The Greeks produced complex dramas, with developed characters, themes and plots that are still present in drama today. With its elaborate masks and costumes and rigidly formalized music, Greek drama has been described as a cross between Japanese Noh theater and grand opera.

The word “drama” is derived from Greek words meaning “to do” or “to act.” There have traditionally been two types of plays: 1) tragedies (plays with a tragic ending) and comedies (plays that are funny). Explaining why comedies exist is easy: people like to be entertained and amused. Understanding why tragedies exist is more difficult to grasp. Aristotle explains that at least part of the attraction is the purging effect of releasing emotion while watching a play.

Greek dramas never had more than three actors on stage at one time. Action in the plays was held to a minimum and violence occurred only offstage. Music was supplied by a flutist who led the chorus. The chorus ceremoniously entered and exited at the opening and closing of a play.

See Separate Article: THEATER AND DRAMA IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Dance

The ancient Greeks believed that dance originated in Crete when Zeus was born to Rhea, the Earth mother. According to a famous myth Rhea’s husband Cronus (Time), fearing he would be overthrown by his offspring, devoured each one at birth. After Zeus was born Rhea deceived Cronus by making a quick switch so that Cronus consumed a stone rather than baby Zeus, who in the meantime was hidden with Curetes of Crete, who danced around him making a ruckus to disguise his cries. In Greek literature and art there are many example of dancing deities. [Source: Libby Smigel, "International Encyclopedia of Dance", editor Jeane Cohen]

Dancers were depicted on frescoes, reliefs and vase paintings. The oldest example is an inscription on a vase, dated to the 8th century B.C., given out as a trophy to a dancer. It reads: “Whoever of the dancers makes merry most gracefully, let him receive this.” Socrates was a great fan of dancing and extolled its virtues. Plato on the other hand believed it undermined noble character and called for severe punishments for those engaged on orgiastic dancing and demanded that lewd suggestive dancing be taken out of comedies.

Images of dancers suggest natural movements. Some Greek dancers used to cover themselves completely from head to foot with clothing and do a dance. Spartan men danced with their armor to increases their strength.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK DANCE europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Music

We do not know for sure what ancient Greek music sounded like because it was never written down. Most Greeks songs consisted of a single melody repeated in unison by singers and musical instruments. There were songs for all different occasions: working, celebrating, birth, death and drinking.

The Greeks ranged tones in scales called “ modes” . Two of these scales provided the basis for music in the Western world. In the 6th century B.C., Pythagoras accurately determined the numerical relationships between strings that produced tones at different pitches.

Music, dance, poetry and drama were all intertwined. Choruses played an important role in dramas and festivals featured poet-musicians competitions. The amateurs performed recited poems accompanied by lyre or a cithara. See Poetry and Drama.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK MUSIC europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024