Home | Category: Culture and Sports

ANCIENT GREEK DANCE

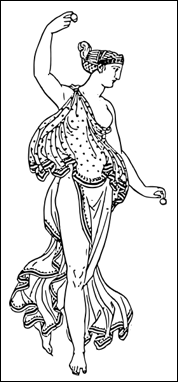

dancing maenad

The ancient Greeks believed that dance originated in Crete when Zeus was born to Rhea, the Earth mother. According to a famous myth Rhea’s husband Cronus (Time), fearing he would be overthrown by his offspring, devoured each one at birth. After Zeus was born Rhea deceived Cronus by making a quick switch so that Cronus consumed a stone rather than baby Zeus, who in the meantime was hidden with Curetes of Crete, who danced around him making a ruckus to disguise his cries. In Greek literature and art there are many example of dancing deities. [Source: Libby Smigel, "International Encyclopedia of Dance", editor Jeane Cohen]

Dancers were depicted on frescoes, reliefs and vase paintings. The oldest example is an inscription on a vase, dated to the 8th century B.C., given out as a trophy to a dancer. It reads: “Whoever of the dancers makes merry most gracefully, let him receive this.” Socrates was a great fan of dancing and extolled its virtues. Plato on the other hand believed it undermined noble character and called for severe punishments for those engaged on orgiastic dancing and demanded that lewd suggestive dancing be taken out of comedies.

The character of Greek dancing was largely mimetic, the movements of the arms and the use of the drapery being very important. The terracotta dancers are good illustrations of this. Images of dancers also suggest natural movements. Some Greek dancers used to cover themselves completely from head to foot with clothing and do a dance. Spartan men danced with their armor to increases their strength.

After reading books by famous archaeologists and studying Greek vases and statues in museums, the American dancer Isadora Duncan developed a style of dance in the 1920s based on her imagery of seductive Greek dancers at Dionysian festivals. In her performance she shocked her well-heeled audiences by dancing in revealing Grecian tunics that exposed her legs and clung to her body. In Boston, she reportedly danced in the nude. Explaining how she arrived at her theory of "free dance," she later recalled, "For hours I would stand quite still, my two hands folded between my breast, covering the solar plexus...I was seeking and finally discovered the central spring of all movement, the creator of the motor power, the unity from which all diversities of movement are born, the mirror of vision for the creation of the dance.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Dance and Ritual Play in Greek Religion” by Professor Steven H. Lonsdale (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Dance in Ancient Greece “ by Lillian B. Lawler (1965) Amazon.com;

“Dances of the Gods Festivals in Ancient Greek Mythology”

by Oriental Publishing (2025) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Music” by M. L. West (1994)

Amazon.com;

“Greek Music Drama” by Friedrich Nietzsche Amazon.com;

“Music in Ancient Greece: Melody, Rhythm and Life” (Classical World)

by Spencer A. Klavan (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Music in the Ancient World: East and West” by Curt Sachs (2008) Amazon.com;

“Music in Ancient Greece and Rome” by John G Landels Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Holidays” by Mab Borden (2024) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of Attica: An Archaeological Commentary” by Erika Simon (1983) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of the Athenians” by H. W. Parke (1977) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies” (Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents) by Peter Wilson (2007) Amazon.com;

“Maenads Early Dionysiac Rites” by Michaela Panajotova Yordanova (2017) Amazon.com;

“Dionysus: Myth and Cult” by Walter F. Otto (1995) Amazon.com;

“Dionysos: Exciter to Frenzy: a Study of the God Dionysos: History, Myth and Lore” by Vikki Bramshaw Amazon.com;

“Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore” by Jennifer Larson (2001) Amazon.com;

Purposes of Dance in Ancient Greece

dancer The earliest dances are thought to have been parts of rituals — in which leaders read poems accompanied by music and dance — that were performed at important milestones such as births, marriages, deaths, harvest festivals, athletic events and military victories. Dances appears to have been part of the education of children, Girls are depicted on vases dancing with clappers under the supervision of instructors. With boys, dance training was part of training for sports and the military.

The chief use of the dance was for religious purposes. In the most ancient times solemn dances were always a part of worship; merry dances were part of the service of Dionysus; and sometimes both sexes took part in these choric dances, but even here there was no question of round dancing, but only of a series of movements regulated by music, and of a dignified and rhythmical character. Dancing formed a part of worship in from the earliest times. A rude clay groups of men and women dancing in a ring illustrate a feature of the worship of Aphrodite in Cyprus.

Dance was also a popular form of entertainment. There are a number of descriptions of such dances in the “Iliad” and “Odyssey”. They appear to have been featured at banquets and were performed along with dramas at weddings. Based on descriptions in the “Odyssey” it seems like participants in feasts and wedding parties mostly sat back and watched. One episode at a double wedding features a king playing a lyre while acrobats perform moves and dance among the guests. There are few descriptions of audience members joining in. We do not find dance mentioned among the usual subjects of instruction, except, indeed, at Sparta. Dancing was a popular amusement, especially as an entertainment during banquets and drinking feasts; but the guests did not dance themselves, but contented themselves with looking on at professional performers. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Still, no doubt, it sometimes happened that when the revellers had drunk a good deal of wine, they felt inspired to join the dance; there were certainly opportunities for learning it, since we are expressly told that Socrates took lessons in dancing at an advanced age. It is almost always solo dancing that is in question; this consisted chiefly in rhythmic movements of hands and feet in a variety of well-chosen postures, and was essentially connected with gymnastics, in which the training in dancing was sometimes included. Dancing together by people of different sexes, such as is customary with us, was unknown in the social life of antiquity, and would in any case have been impossible in Greece, owing to the separation which existed in ordinary life between men and women.

Professional Dancers in Ancient Greece

Professional dancers, both boys and girls, were employed to furnish entertainment at symposia. On a kylix is a girl dancing and playing the castanets, while a young man looks on. Women of good family danced at home for amusement, and at domestic festivals. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

In the “Banquet” of Xenophon, at an early stage of the proceedings, a Syracusan appears, who has been invited by the host, with a flute girl, a dancing girl, and a beautiful boy who plays a harp and dances. They play and perform pantomimic dances; in particular, there is a full description of one such dance, which represents in very graceful fashion the meeting of Ariadne with Dionysus. Conjurers, too, so-called “Thaumaturgists,” show their skill on these occasions. . [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The dancing girl in Xenophon’s “Banquet” throws twelve rings into the air while dancing, and catches them all in turn; then she performs a bold sword dance, turning head over heels into a stand round which sharp knives are set, and out again in the same fashion. We often find similar representations on vase paintings; thus, it shows a girl walking on her hands and performing a dangerous dance between sharp swords. In a similar posture the woman represented in one image shoots an arrow with her toes from a bow held between her feet.

See Separate Article: SYMPOSIUM IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Types of Ancient Greek Dance

There were two primary kinds of dances: circular ones around an altar or votive offering and lines dances performed during processions. In general men and women danced separately. There are deceptions in the “Iliad” and other places of men and women dancing together holding hands. Vase images of dancers dressed in costumes resembling birds, horses and bulls suggested the Greeks performed dances mimicking these animals. Some comedies such as Aristophanes “Birds” have people dressed as animals in the chorus

The dances in armour which were popular in the Doric states, and were, of course, only performed by men, were of a livelier character.The dancers were equipped with helmet, shield, and sword, and went through a number of choregraphic evolutions; the dances at country festivals, which very often had a pantomimic character, were also of a lively nature. Here, as well as in the solemn religious dances, it was very common for the dancers to sing as they danced, and sometimes even accompany themselves on some instrument; in fact, this distinction holds good between dancing in ancient and in modern times, that in antiquity it was not an object in itself, but was always closely connected with the other musical arts. The ancient dance attained its highest development and perfection in the drama, where dancing, music, and pantomime were most perfectly combined; but we shall have occasion to refer to this later on, in discussing the theatre of the Greeks. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Pyrrhic dances (dances with weapons) were invented by Greeks but popularized by Romans. Pyrrhic dancers were commonly painted on vases designed to hold oil. On these vases dancers are shown doing their steps and movements wearing full body armor, apparently to develop their strength and skill in military sports and for battle itself. The same movements were sometimes performed in dances performed by the chorus at poetry contests. The “anapale”, a dance with wrestling movements originated in Sparta. Pyrrhic dances were performed during military campaigns. There are description of them being performed for ambassadors and special guests.

Cordax

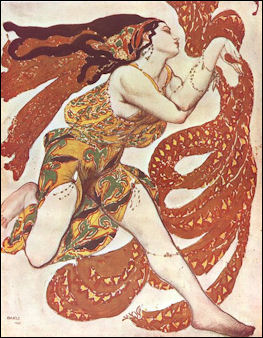

Terracotta dancing maenad The cordax was a provocative, licentious, and often obscene mask dance performed in ancient Greek comedies. In his play The Clouds, Aristophanes complains that other playwrights of his time tried to hide the feebleness of their plays by bringing an old woman onto the stage to dance the cordax. He noted with pride that his patrons did not find such gimmicks in his plays. The dance can be compared with the modern Tsifteteli (a belly-dance-like dance of Anatolia and the Balkans). [Source: Wikipedia +]

The cordax was performed by actors and the chorus in Greek comedies. The first mention of it dates to the 5th century B.C. It was performed by men and women in groups and solo. Descriptions mention kicking the buttocks, rotating the hips, slapping the thighs and leaping. Plato was among the philosophers and orators that denounced the dance as degenerate and associated it with drunkenness. Demosthenes derided a vulgar performance of the dance in the court of Philip of Macedon. [Source: Encyclopedia of Dance]

Petronius Arbiter in his Roman novel the Satyricon has Trimalchio boast to his dinner guests that no one dances the cordax better than his wife, Fortunata. The nature of this dance is described in the satires of Juvenal, who says "the girls encouraged by applause sink to the ground with tremulous buttocks." The poet Horace and playwright Plautus refer to the same dance as iconici motus. Juvenal makes specific mention of the testarum crepitus (clicking of castanets). In the earlier Greek form, finger cymbals were used. +

Festival Dancing in Ancient Greece

Dancing was usually performed at festivals and poetry competitions. To pay their respect to Dionysus, the citizens of Athens, and other city-states, held a winter-time festival in which a large phallus was erected and displayed. After competitions were held to see who could empty their jug of wine the quickest, a procession from the sea to the city was held with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and maenads (nymphs), which were often paired together. At the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Dancing was usually performed at festivals and poetry competitions. To pay their respect to Dionysus, the citizens of Athens, and other city-states, held a winter-time festival in which a large phallus was erected and displayed. After competitions were held to see who could empty their jug of wine the quickest, a procession from the sea to the city was held with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and maenads (nymphs), which were often paired together. At the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of iv and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The main purveyors of the Dionysus fertility cult "These drunken devotees of Dionysus," wrote Boorstin, "filled with their god, felt no pain or fatigue, for they possessed the powers of the god himself. And they enjoyed one another to the rhythm of drum and pipe. At the climax of their mad dances the maenads, with their bare hands would tear apart some little animal that they had nourished at their breast. Then, as Euripides observed, they would enjoy 'the banquet of raw flesh.' On some occasions, it was said, they tore apart a tender child as if it were a fawn'"μ

One time the maenads got so involved in what they were doing they had to be rescued from a snow storm in which they were found dancing in clothes frozen solid. On another occasion a government official that forbade the worship of Dionysus was bewitched into dressing up like a maenad and enticed into one of their orgies. When the maenads discovered him, he was torn to pieces until only a severed head remained.μ

It is not totally clear whether the maenad dances were based purely on mythology and were acted out by festival goers or whether there were really episodes of mass hysteria, triggered perhaps by disease and pent up frustration by women living in a male-dominate society. On at least one occasion these dances were banned and an effort was made to chancel the energy into something else such as poetry reading contests.

See Separate Article: DIONYSUS CULT: MAENADS, MYSTERIES, THEATER AND WILD FESTIVALS europe.factsanddetails.com

Dancing Girls in Ancient Greece

maenad

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: “Lipsius discourses on public prostitutes in the theatre. Telethusa and Quinctia were probably Gaditanian damsels who combined the professions of dancer and harlot. These dancing girls were called saltatrices. Ovid in his Amores, speaks of dancing women: 'One pleases by her gestures, and moves her arms to time, and moves her graceful sides with languishing art in the dance; to say nothing about myself, who am excited on every occasion, put Hippolytus there — he would become a Priapus.' Dancing was in general discouraged amongst the Romans. During the Republic and the earlier periods of the Empire women never appeared on the stage, but they frequently acted in the parties of the great. These dancing girls accompanied themselves with music (the chief instrument being the castanet) and sometimes with song. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

” In the Banquet of Xenophon reference is made to their agility and intelligence: “Immediately Ariadne entered the room, richly dressed in the habit of a bride, and placed herself in the elbow-chair ... Then a hoop being brought in with swords fixed all around it, their points upwards, and placed in the middle of the hall, the dancing-girl immediately leaped head foremost into it through the midst of the points, and then out again with a wonderful agility ... I see the dancing-girl entering at the other end of the hall, and she has brought her cymbals along with her ... At the same time the other girl took her flute; the one played and the other danced to admiration; the dancing-girl throwing up and catching again her cymbals, so as to answer exactly the cadency of the music, and that with a surprising dexterity.

“The costume of female acrobats was of the scantiest. In some designs the lower limbs of the figures are shown enveloped in thin drawers. From vase paintings we see that female acrobatic costume sometimes consisted solely of a decorated band swathed round the abdomen and upper part of the thighs, thus resembling in appearance the middle band adopted by modern acrobats. Juvenal speaks of the 'barbarian harlots with embroidered turbans', and the girls standing for hire at the Circus; and in Satire XI he says, 'You may perhaps expect that a Gaditanian singer will begin to tickle you with her musical choir, and the girls encouraged by applause sink to the ground with tremulous buttocks.' This amatory dancing with undulations of the loins and buttocks was called cordax; Plautus and Horace term a similar dance Iconici motus. Forberg, commenting on Juvenal, says, 'Do not miss, reader, the motive of this dance; with their buttocks wriggling the girls finally sank to the ground, reclining on their backs, ready for the amorous contest. Different from this was the Lacedaemonian dance bíbasis, when the girls in their leaps touched their buttocks with their heels. Aristophanes in Lysistrata writes — 'Naked I dance, and beat with my heels the buttocks.' And Pollux, 'As to the bíbasis, that was a Laconian dance. There were prizes competed for, not only amongst the young men, but also amongst the young girls; the essence of these dances was to jump and touch the buttocks with the heels. The jumps were counted and credited to the dancers. They rose to a thousand in the bíbasis.' Still worse was the kind of dance which was called "eklaktisma", in which the feet had to touch the shoulders.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024