Home | Category: Literature and Drama

ANCIENT GREEK LITERATURE

Plato Symposium papyrus As a rule Greek literature and drama was meant to be read and heard aloud not to be read quietly from a book. Most classic works were recited by traveling bards or written for drama competitions. Reading wasn’t popular because reading from unrolled scroll was not an easy thing to do.

Myth and the Homeric epics infused everyday life. By examining literature and drama, historians have been able to draw great insights into everyday Greek life.

Translating Greek literature and poetry presents great difficulty because Greeks phrases tend to express things that the English language needs at least twice as many words to express. Literal translations of Greek are awkward and repetitive. The best translations are often the ones that have taken the most liberties. any Greek words have multiple meanings or meanings that are difficult to translate exactly.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of Ancient Greek Literature” (Classic Reprint) by Gilbert Murray (1866-1957) Amazon.com;

“Anthology of Ancient Greek Popular Literature” by William Hansen (1998) Amazon.com;

“Collected Ancient Greek Novels” by B. P. Reardon, J. R. Morgan (2019) Amazon.com;

“Yale Classics - Ancient Greek Literature: Mythology, History, Philosophy, Poetry, Theater (Including Biographies of Authors and Critical Study of Each Work)

by Homer, Hesiod, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World” by Roy MacLeod | (2004) Amazon.com;

“Monsters in Greek Literature: Aberrant Bodies in Ancient Greek Cosmogony, Ethnography, and Biology” by Fiona Mitchell (2021) Amazon.com;

“Aesop's Fables” By Aesop, Illustrated Amazon.com;

“Eros the Bittersweet” by Anne Carson (1986) Amazon.com;

“Theogony: Works and Days” by Hesiod (Oxford World's Classics) Amazon.com;

“The Iliad And The Odyssey of Homer” by Homer Amazon.com;

“If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho” by Sappho, translated by Anne Carson Amazon.com;

“Stung with Love: Poems and Fragments” (Penguin Classics) by Sappho Amazon.com;

Scrolls in Ancient Greece and Reading Them

The Egyptian and Greeks wrote on papyrus or parchment with expensive inks or chiseled letters into stone. Romans commonly used small wooden tablets covered with a thin coat of wax, on which words could be inscribed with a sharp object and then the wax could be smeared again and new words could be written. The first books were perhaps sheets of wood coated and bound together (the first books in fact were called "codexes," meaning "tree trunk board"). ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

The averages scroll was perhaps 40 feet long and the longest were 150 feet. To cover a long story took several scrolls. The “ Iliad” and “ Odyssey” , for example, required 36 scrolls. Compared to books they had many disadvantages. Suppose you wanted to took look up something in the middle of a scroll you had to unwind it to the place you wanted and then wind back for the next person (the same way you should rewind a video cassette after watching a movie). Furthermore scrolls were relatively fragile. Every time one was unrolled and rolled that was wear and tear on the scroll. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Mary Beard, a professor of classics at Cambridge University, wrote in the New York Times: The books Greeks and Romans read “were not “books” in our sense but, at least up to the second century. The “book rolls” “long strips of papyrus, rolled up on two wooden rods at either end. To read the work in question, you unrolled the papyrus from the left-hand rod, to the right, leaving a “page” stretched between the two. It was considered the height of bad manners to leave the text on the right hand rod when you had finished reading, so that the next reader had to rewind back to the beginning to find the title page, bad manners — but a common fault, no doubt, Some scribes helpfully repeated the title of the books at the very end, with just this problem in mind.”

“These cumbersome rolls made reading a very different experience than it is with the modern book,” Beard wrote. “Skimming, for example, was much more difficult, as looking back a few pages to check out the name you had forgotten (as it is on Kindle). Not to mention the fact that at some periods of Roman history, it was fashionable to copy a the text with no breaks between words, but as a river of letters. In comparison, deciphering the most challenging postmodern text (or “Finnegan’s Wake,” for that matter) looks easy.”

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK LANGUAGE: HISTORY, DEVOPMENT, WRITING, ALPHABETS, SOUNDS europe.factsanddetails.com

Books and Libraries in Ancient Greece

The first books, or codexes, had no page numbers or table of contents. The author was seldom identified, but the scribe often was. He after all was the one who did all the work to make the book. Parchment, unlike papyrus, could be written on both sides. To make a codex, the ends of sheets were folded and sewn together.

Popular novels and treatises were "published" in Roman times by teams of slave scribes who copied the work by hand onto papyrus scrolls with ink made of soot, resin, wine dregs and cuttlefish. In ancient Greece books were so common that jokes were made in Greek comedies about book worms.

Early libraries were located in temples, public baths and palaces. The scrolls for books like the “ Iliad” and “ Odyssey” were kept in buckets and stored on shelves. There was no Dewey decimal system. Books were organized haphazardly and often not labeled. If you were looking for a particular book it was probably hard to find.

Book: “ Libraries in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (Yale University Press, 2001)

Alexandria Library

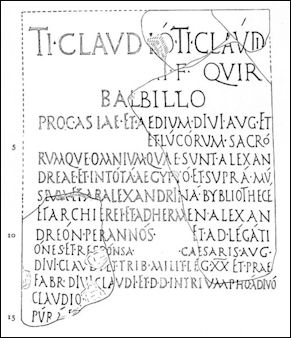

Alexandria Library Inscription The great library of Alexandria was “first ample repository of the west's literary inheritance." It was inaugurated by in 298 B.C. Ptolemy I. According to legend Alexandria the Great envisioned a great library but it was Ptolemy I who proposed collecting “books of all the peoples of the world.” He sent letters to rulers in the known world and asked them for works by “poets, and prose-writers, rhetoricians and sophists, doctors and soothsayers, historians.” "Ptolemy II enlarged the library, adding a museum and research center. [Source: Alexander Stille, New Yorker, May 8, 2000, Lionel Casson, Smithsonian Magazine.

Before the establishment of the Alexandria Library, most book collections belong to private owners. Aristotle and Alexander the Great supposedly had large libraries. Libraries were not a new idea. The Egyptians built papyrus libraries in 3200 B.C. and Athens had a library in the 4th century. But the size and scope of the Alexandria Library was on a scale the world had never seen.

Probably modeled on the Lyceum, Aristotle’s library and school in Athens, the Alexandria Library was located in the Mouseion, the Temple of Muses. No one knows exactly where that was except that it was part of the Royal Court of the Ptolemy, a huge complex that covered a large area and included a zoo and botanical gardens.

According to Strabo, who visited Alexandria in 20 B.C., the library "was part of the royal palaces, it had a walk, an arcade, a large house in which was a refractory for members of the Mouseion."

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ALEXANDRIA: HISTORY, LIBRARY, SEVEN WONDERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Sex and Literature in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek literature is filled with sex, violence and scandal. Some of the most famous works by Aristophanes — including “The Birds” , “Lysistrata” and especially “Women at the Thesmoporia” “are filled with obscenities and sexual innuendos. The reasons why some of the works are relatively clean today — and more boring than the otherwise might be — is that many of the translations were done by Victorian era Britons.

Greek dramas often featured liberal use actors of with giant phalluses and references to homosexuality. In “ Clouds” Aristophanes wrote: "How to be modest, sitting so as not to expose his crotch, smoothing out the sand when he arose so that the impress of his buttocks would not be visible, and how to be strong...The emphasis was on beauty...A beautiful boy is a good boy. Education is bound up with male love, an idea that is part of the pro-Spartan ideology of Athens...A youth who is inspired by his love of an older male will attempt to emulate him, the heart of educational experience. The older male in his desire of the beauty of the youth will do whatever he can improve it."

In Aristophanes's “ The Birds” , one older man says to another with disgust: "Well, this is a fine state of affairs, you demanded desperado! You meet my son just as he comes out of the gymnasium, all rise from the bath, and don't kiss him, you don't say a word to him, you don't hug him, you don't feel his balls! And you're supposed to be a friend of ours!"

Ancient Greek Mythology

Mythology, literature and religion were intertwined in ancient Greece and Rome. Many elements and figures in Greek religion and mythology have become important elements and icons in modern European and American culture. The word myth comes from “ mythos” , the Greek word which meant both “truth” and “word.”

Myths were popular in ancient times because they helped explain the complexities of the universe in ways that human beings could understand and also explained things in the past that no one observed directly. Myths appeared in many culture to explain things like why the sun disappeared at night and reappeared in the day; to sort out why natural disasters occur; explain what happens to people when they die; to create a credible story as how the universe and mankind were created. Because so many of things were unexplainable it was simple enough to create gods and say did the did the unexplainable things.

The myths on similar subjects—such as the coming of spring and the presence of gods in the sky — are often remarkably similar in cultures that have and never have had contact with one another. Flood stories after creation, for example are very common. By the same token, the telling of a certain myth can vary in small ways and in large between groups of a certain time period or area within a culture.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY AND GODS europe.factsanddetails.com

Theater and Drama in Ancient Greece

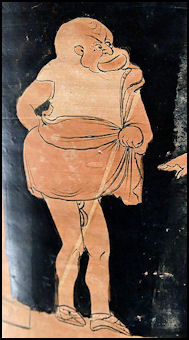

Theater slave The Greeks are regarded as the inventors of drama. The Egyptians produced simple plays about the pharaoh’s birth at his crowning and plays about resurrection at the pharaoh’s funeral. The Greeks produced complex dramas, with developed characters, themes and plots that are still present in drama today. With its elaborate masks and costumes and rigidly formalized music, Greek drama has been described as a cross between Japanese Noh theater and grand opera.

The word “drama” is derived from Greek words meaning “to do” or “to act.” There have traditionally been two types of plays: 1) tragedies (plays with a tragic ending) and comedies (plays that are funny). Explaining why comedies exist is easy: people like to be entertained and amused. Understanding why tragedies exist is more difficult to grasp. Aristotle explains that at least part of the attraction is the purging effect of releasing emotion while watching a play.

Greek dramas never had more than three actors on stage at one time. Action in the plays was held to a minimum and violence occurred only offstage. Music was supplied by a flutist who led the chorus. The chorus ceremoniously entered and exited at the opening and closing of a play.

Ironically, the early forms of the Greek dramatic arts, which puts so many of us to sleep, sprung up out orgiastic Dionysian rites. The first phase of the metamorphosis began in the 7th century B.C. when the frantic dances of the maenads evolved into choral songs called dithyrambs. Dithyrambs were performed by a "circular chorus" of 50 men and boys who sang and danced around an altar in the orchestra area of a theater.

RELATED ARTICLES:

DRAMA IN ANCIENT GREECE: ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, TYPES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK THEATER PERFORMANCES: CONTESTS, ACTORS, MASKS, COSTUMES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDIES: PLOTS, TYPES, STRUCTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

GREAT ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY PLAYWRIGHTS: AESCHYLUS, SOPHOCLES AND EURIPIDES europe.factsanddetails.com

ARISTOPHANES AND ANCIENT GREEK COMEDIES europe.factsanddetails.com

Aesop

“Aesops Fables” are said to date back to around 6th-century B.C. Greece. It is not known whether Aesop was a real person. According to tradition, Aesop lived from about 620 to 560 B.C. and was a clever former slave with a deformed body. After he was freed by his master he made reputation for himself telling stories and was invited to live with Croeseus, King of Lydia. He died in Delphi, where it is said he was sent by Croeseus, and so angered the Delphians he was thrown off a cliff.

If Aesop was a real person it is likely that he was illiterate and didn’t write the fables down. Instead they were passed down orally and first written down in Athens in the 4th century B.C. Later a medieval Greek named Babrius collected them. His copy was lost for over a thousand years and found at a monastery in Mount Athos in 1844. Some of the fables that have been handed down to us today are versions by Jean de la Fontaine, a writer who lived in France in the 17th century.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: For a man whose stories have given shape to our childhoods, and those of hundreds of generations before us, he’s curiously hard to pin down. The earliest reference to him comes from the fifth century B.C. historian Herodotus, who tells us that Aesop was a fabulist who lived roughly two hundred years beforehand. According to the Histories, Aesop was enslaved during his early years and was murdered by the people Delphi. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, February 27, 2022]

The list of ancient writers who know about Aesop and his fables is a veritable Who’s Who of ancient Greek intellectuals, but there’s little about Aesop that they can agree on. Aristotle says that Aesop was born in Mesembria, a Greek colony; the third century B.C. poet Callimachus says that he was from Sardis; Maximus of Tyre called him the “sage of Lydia”; and a slew of ancient authors say he was born in Phrygia.

One of the most consistent things about Aesop’s biography is that he is identified as having been enslaved. This designation is connected to the character of his speech and use of the fable. Howley told me that Phaedrus, a Latin poet who rewrote many of the fables and was himself formerly enslaved, “explains that enslaved people cannot speak plainly, but must learn to speak obliquely in order to survive.” The fable, says Phaedrus, is something that only an enslaved person could devise. Thus, even though all kinds of elite people speak in fables, in the minds of ancient readers the fable was seen to represent what Oxford Professor Teresa Morgan has called “a kind of popular moral philosophy.” This kind of philosophy, Howley agreed, was “associated with enslaved, working, and otherwise disempowered or exploited parts of society.”

Fictional Life of Aesop

Roman take on Aesop

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: There’s a fictional Life of Aesop from the first century CE but it almost certainly represents traditions that grew up around the Aesop legend in the centuries that preceded it. This romance novel preserves many of the biographical details that appear scattered in other ancient sources. According to the oldest and longest version of the Life, our hero began his career as a hideous enslaved man who worked the fields and was unable to speak (Hideous is not an overstatement: one unsavory character likens him to a turnip with teeth and others compare him to garbage). [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, February 27, 2022]

After assisting a lost priestess, however, Aesop receives the gift of speech from the Muses and becomes a “composer of fables.” He is purchased by the philosopher Xanthus and repeatedly outwits his new slaveholder by hilariously following his orders to the letter. In one instance, Xanthus asked Aesop to bring him an oil flask, which Aesop did without filling it with oil. On another occasion, when Xanthus instructed him to prepare a lentil pot for dinner, Aesop responded by cooking a single lentil.

This kind of pedanticism and blunt honesty usually doesn’t win you friends. Even after Aesop was manumitted and began to write fables his directness continued to offend. After insulting the inhabitants of Delphi, he was framed for temple theft. Despite his best storytelling efforts and attempt to claim sanctuary in a shrine dedicated to the Muses, he was forced off a cliff. Aesop had the last laugh, though, as the inhabitants of Delphi were punished three times over for their actions while Aesop achieved immortality through his fables.

As entertaining as it is, the Life of Aesop is less a source for the historical Aesop than it is a sign of the popularity that Aesop and his fables had achieved by the lifetime of Jesus. The “real” Aesop is nowhere to be found. Dr. Joseph Howley, an associate professor of classics at Columbia University and a scholar of Roman culture who studies enslavement and literature in the ancient world, told the Daily Beast that really “Aesop” is just the name we give to the imagined ‘author’ of a tradition of fables that emerged over a long period of time. This is a lot like (spoiler alert) the way the name “Homer” was applied to the imagined author of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Aesop's Fables

Aesop’s fables are simple stories with and having a moral lesson, usually involving animals, which fit stereotypes such as the strong lion or sly fox. The stories are oriented towards children with words of wisdom they are expected to take to heart. Famous Aesop’s fables include the 1) “The Tortoise and the Hare” ; 2) “The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing” ; 3) “The Fox and the Grapes” ; 4) “The Lion and the Mouse” ; 5) “The Fox and the Stork” .

In “The Lion and the Mouse “ a mouse scrambles across the face of a lion and wakes the lion up. The angry lion catches the mouse in his paw and threatens to kill him. The mouse pleads for his life and the lion lets him go. Some time later on the lions gets caught in a hunter’s trap. He roars. He mouse hears the roar, arrives, and gnaws at the ropes of the trap and sets the lion free. The moral: “Sometimes the weakest can help the strongest.”

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast:Chances are that at some point in your life you have run across Aesop’s Fables. Even if no one read you the Hare and the Tortoise as a child, a family member or teacher will have mentioned the Boy who Cried Wolf. These are child-rearing fan favorites that teach values like honesty and the rewards of hard work. Even if you somehow missed a moral education and skipped ahead to the world of finance some boardroom hawk will have mentioned the perils of ‘killing the Golden Goose.’ This saying also comes from Aesop and his morality tales. No ancient Greek figure has been as widely read and illustrated as Aesop, but the truth of the matter is that we don’t know if he even existed. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, February 27, 2022]

When the printing press spread throughout Europe in the fifteenth century, Aesop’s Fables (and the story of his life) was one of the first works to be printed. The enduring popularity of “Aesop” means that he is constantly being told and retold: he has been read as an Ethiopian slave, a critic of industrial capitalism, a Japanese folklore teller, a Christian moralist, and an inspiration for Founding Fathers. Perhaps part of his appeal lies both in his status as an outsider and his malleability in the hands of his readers. Just as “Aesop” uses animals to speak about the realities of power, we use a mistreated outsider to talk about the human condition. There’s something alarming about that kind of appropriation, but there’s also something revealing and even Aesopic about it. In the long arc of the battle for cultural immortality, chickens come home to roost, the marginalized will have their say, and justice will out. And as we all know, slow and steady wins the race.

Evolution of Aesop’s Fables

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: When the Life of Aesop took on literary shape in the first century CE collections of Aesopic fables were being re-written by people like Phaedrus and the Greek poet Babrius. The fables, like the Life, were in a state of interpretative flux. Writers like Phaedrus and Babrius saw themselves as participating in an unproblematic tradition of retelling that involved expansion and interpretation. The origin of these traditions was Aesop, but it was socially acceptable to re-tell those traditions. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, February 27, 2022]

As a mode of communicating, fables could serve a number of purposes, but they were generally seen as a fictitious and entertaining way to explain some aspect of life. The literati may have seen them as children’s tales for the uneducated, but even illustrious orators like Demosthenes had to recognize that people from all walks of life prefer to hear stories about donkeys to ponderous speeches. This doesn’t make them useless. Even animal tales can contain important ethical lessons and create what Morgan calls an “ethical landscape.” That’s why we teach them to our children, after all.

The landscape of the Aesop’s Fables, however, is a little vaguer about the traditional social virtues than we might think. Morgan notes that “friendship, trust, reliability, and honesty” are recommended, but only in a guarded manner. There’s a sort of pragmatic virtue at work here that emphasizes survival rather than principles. The world of the Aesopic corpus may not be as emancipatory or black and white as we might hope, but it is still a world in which the powerful are constrained by practicalities and the weak can survive through cleverness and co-operation. Neither Aesop nor Phaedrus’s fables are idealistic — their worlds are full of immovable hierarchies and threats of violence — but they do paint a picture of a world in which justice is omnipresent. Honesty may not always serve you well, and it certainly didn’t for Aesop himself, but you will always reap what you sow.

Whether we are talking about Aesop and his story or the fables themselves we are encountering a cultural mishmash of ideas and influences. The Life of Aesop follows the literary conventions of the ancient romance novel and borrows from other stories. The most popular version uses elements of the Sayings of A iqar, an Aramaic text about a different fifth century B.C. sage. Some of the Fables, too, seem to come from non-Greek sources. What this means is that both the man and the text are composite of a variety of cultures and traditions. “What fascinates me most about Aesop” said Howley “is that although the Greek tradition claims him and his fables, it always registers him as an outsider…The fact that some of his surviving fables appear in Akkadian, Egyptian, and other traditions leads me to think of Aesop as something of a fig leaf, a figure invented by the Greeks to mask their assimilation and co-opting of other, earlier traditions from West Asia and North Africa.”

Chances are that at some point in your life you have run across Aesop’s Fables. Even if no one read you the Hare and the Tortoise as a child, a family member or teacher will have mentioned the Boy who Cried Wolf. These are child-rearing fan favorites that teach values like honesty and the rewards of hard work. Even if you somehow missed a moral education and skipped ahead to the world of finance some boardroom hawk will have mentioned the perils of ‘killing the Golden Goose.’ This saying also comes from Aesop and his morality tales. No ancient Greek figure has been as widely read and illustrated as Aesop, but the truth of the matter is that we don’t know if he even existed.

Homer, The Iliad and The Odyssey

Homer is a person said to have written “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey”. He was the most important and earliest of the Greek and Roman writers. His influence was not only on literature, but ethics and morality as well. Homer is sometimes credited with the Homeric Hymns. However, scholars think these must have been written more recently than the Early Archaic period.

No one knows whether Homer was a he or she, or even a real person. The ancient Greeks believed he was a blind, itinerant bard who was born in Smyrna (present-day Izmir, Turkey) and lived in Chios (a Greek island near the coast of Turkey). Chios was famous for its epic singers and many people on the island called themselves “Homeridae” , the descendants of Homer. But these are far from universally-agreed-upon facts. Colophon, Salamis, Rhodes, Argos and Athens also claim to be his birthplace. There is no evidence that he was blind although a well-known bust of the poet suggests it.

In Homer's time, stories were generally heard or spoken rather than read or written. People who memorized stories spoke them at public performances to share the stories and entertain the people. It was in this manner that The Odyssey and stories like it could be passed onto new generations in a culture without an alphabet.In ancient Greek, Homer’s poems were recited by rhapsodes (song- stitchers) who could add their own personal and cultural touches depending on where and when the stories were told. It seems likely that some rhapsodes were better than others. Homer himself said: “So it is that the gods do not give all men gifts of grace - neither good looks nor intelligence nor eloquence.”

The “Iliad” is the oldest surviving European poem. Not a "true story," but based on major events that may have happened around 1500 to 1200 B.C., it describes the Trojan War between the Trojans and the Myceneans, which the Trojans lost even though they fought like "ravening lions." Consisting of 24 books written in dactylic hexameter, the “Iliad” addresses timeless themes like honor, morality, friendship. the horror of war, mortality and death.

The “Odyssey” is the tale of Odysseus's journey home after the Trojan War. Attributed to Homer, who lived around 850 B.C., it is very different from Homer's other book,the “ Iliad”. Rather than being about battles and brave warriors who use their power and strength to take matters into their own hands it is about a single warrior whose power and strength are no match against the whims and capriciousness of the gods and who must learn to deal with a fate over which he has no control. Much of The “ Odyssey” is about setback and delays. The crew is often complaining about something and Odysseus is not great fan of the open sea.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HOMER: HIS WORKS, HYMNS AND STYLE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

RHAPSODES: THE SINGING BARDS OF HOMERIC-ERA AND CLASSICAL GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ILIAD: PLOT, CHARACTERS, BATTLES, FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

ODYSSEY: PLOT, ODYSSEUS'S ADVENTURES AND THE CREATURES HE ENCOUNTERS europe.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Greek Poetry

Greek poetry and music included epic stories, drinking songs, religious and processional hymns, funeral dirges, wedding songs, love poems, drama dialogues, and odes to the Gods and heros. Even political speeches had poetic elements. Poetry and verse were considered far superior to prose. The Greeks didn’t have a word for prose until decades after Herodotus developed it as a separate style and then it was referred to simply as “psilos logos” (“naked language”) and “pedzos logos” (“walking language”) as opposed to the “dancing or even airborne language of poetry.” [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker]

Vowels in the ancient Greek language had both pitch-accent and quantity (time value) unlike the stressed syllables of modern Greek. Thus the syllables of a line of poetry created prosodic rhythm with the long vowels receiving twice the time value as short vowels.

The Greeks were using iambic meter by the 7th century B.C. It was often associated with great orators such as Solon and Archilochus. A little bit later free, more expressive “ lyric” poetry was introduced. The Greeks called it “ medic” poetry. We use the word lyrical because poets who recited it were often accompanied by a lyre.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT GREEK POETRY europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024