Home | Category: Culture and Sports

ANCIENT GREEK MUSIC

music, wine, ecstacy We do not know for sure what ancient Greek music sounded like because it was never written down. Most Greeks songs consisted of a single melody repeated in unison by singers and musical instruments. There were songs for all different occasions: working, celebrating, birth, death and drinking.

The Greeks ranged tones in scales called “ modes” . Two of these scales provided the basis for music in the Western world. In the 6th century B.C., Pythagoras accurately determined the numerical relationships between strings that produced tones at different pitches.

Music, dance, poetry and drama were all intertwined. Choruses played an important role in dramas and festivals featured poet-musicians competitions. The amateurs performed recited poems accompanied by lyre or a cithara. See Poetry and Drama.

According to the The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Music was essential to the pattern and texture of Greek life, as it was an important feature of religious festivals, marriage and funeral rites, and banquet gatherings. Our knowledge of ancient Greek music comes from actual fragments of musical scores, literary references, and the remains of musical instruments. Although extant musical scores are rare, incomplete, and of relatively late date, abundant literary references shed light on the practice of music, its social functions, and its perceived aesthetic qualities. Likewise, inscriptions provide information about the economics and institutional organization of professional musicians, recording such things as prizes awarded and fees paid for services. The archaeological record attests to monuments erected in honor of accomplished musicians and to splendid roofed concert halls. In Athens during the second half of the fifth century B.C., the Odeion (roofed concert hall) of Perikles was erected on the south slope of the Athenian akropolis—physical testimony to the importance of music in Athenian culture. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001, metmuseum.org \^/]

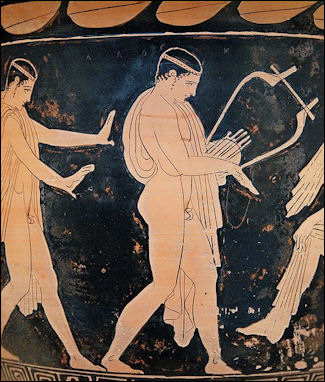

“In addition to the physical remains of musical instruments in a number of archaeological contexts, depictions of musicians and musical events in vase painting and sculpture provide valuable information about the kinds of instruments that were preferred and how they were actually played. Although the ancient Greeks were familiar with many kinds of instruments, three in particular were favored for composition and performance: the kithara, a plucked string instrument; the lyre, also a string instrument; and the aulos, a double-reed instrument. Most Greek men trained to play an instrument competently, and to sing and perform choral dances. Instrumental music or the singing of a hymn regularly accompanied everyday activities and formal acts of worship. Shepherds piped to their flocks, oarsmen and infantry kept time to music, and women made music at home. The art of singing to one's own stringed accompaniment was highly developed. Greek philosophers saw a relationship between music and mathematics, envisioning music as a paradigm of harmonious order reflecting the cosmos and the human soul.” \^/

Sometimes music and poetry contests were staged in conjunction with Olympic-style athletic competitions. Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “There was anciently a contest held at Delphi, of players on the cithara, who executed a paean in honor of the god. It was instituted by the Delphians. But after the Crisaean war the amphictyons, in the time of Eurylochus, established contests for horses and gymnastic sports, in which the victor was crowned. These were called Pythian games, in addition to the musical contests.” [Source: Fred Morrow Fling, ed., “A Source Book of Greek History,” Heath, 1907, pp. 47-53]

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Greek Music” by M. L. West (1994)

Amazon.com;

“Greek Music Drama” by Friedrich Nietzsche Amazon.com;

“Music in Ancient Greece: Melody, Rhythm and Life” (Classical World)

by Spencer A. Klavan (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Rise of Music in the Ancient World: East and West” by Curt Sachs (2008) Amazon.com;

“Music in Ancient Greece and Rome” by John G Landels Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Music: A New Technical History” (Reprint)

by Stefan Hagel Amazon.com;

“Dance and Ritual Play in Greek Religion” by Professor Steven H. Lonsdale (1993) Amazon.com;

“Mode in Ancient Greek Music” (Cambridge Classical Studies)

by R. P. Winnington-Ingram (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Dance in Ancient Greece “ by Lillian B. Lawler (1965) Amazon.com;

“Dances of the Gods Festivals in Ancient Greek Mythology”

by Oriental Publishing (2025) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Greek Holidays” by Mab Borden (2024) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of Attica: An Archaeological Commentary” by Erika Simon (1983) Amazon.com;

“Festivals of the Athenians” by H. W. Parke (1977) Amazon.com;

“The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies” (Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents) by Peter Wilson (2007) Amazon.com;

“Dionysus: Myth and Cult” by Walter F. Otto (1995) Amazon.com;

“Dionysos: Exciter to Frenzy: a Study of the God Dionysos: History, Myth and Lore” by Vikki Bramshaw Amazon.com;

“Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore” by Jennifer Larson (2001) Amazon.com;

Pythagoreans and Music

The Pythagoreans were followers of the philosopher-mathematician Pythagoras. Headquartered first on the island of Samos and later Croton in southern Italy, they were the first to make the profound discovery that all aspects of nature — musical notes, mathematics, science, architecture and engineering — followed rules that were determined by the relationship between numbers.

Pythagorians The Pythagoreans showed how numbers could be used to describe the harmonies and beauties of music and introduced the musical terminology of the octave, the fifth, the forth, expressed as 2:1, 3:1 and 4:3. They found that the most pleasant sounds occurred in exact proportions and discovered that the length of a musical string was is in an exact numerical relation to the pitch of its tone.

Notes are sound waves created by vibrations. A vibration that is twice as high as another is an octave. Others that are pleasant together are those whose vibration are a forth or fifth higher. These same proportions are used in designing what are regarded as aesthetically pleasing building, which is why architecture has been called “frozen music.” The Pythagoreans argued that of numbers worked so well describing music they could also describe everything in the universe. Describing the Pythagoreans in his “Metaphysics” , Aristotle wrote: "they say that the things themselves are Numbers and do not place the objects of mathematics between Forms and sensible things...Since, again, they saw that the modifications and the ratios of the musical scales were expressible in numbers — since, then, all other things seemed in their whole nature, they supposed the elements of numbers to be the elements of all things, and the whole heaven to be a musical scale and a number...and the whole arrangement of the heavens they collected and fitted into their scheme; and if there was a gap anywhere, they readily made additions so as to make their whole theory coherent."

See Separate Article: PYTHAGOREANS: THEIR STRANGE BELIEFS, PYTHAGORAS, MUSIC AND MATH factsanddetails.com

Music and Festival Entertainment in Ancient Greece

Xenophon (c430-354 B.C.) wrote in Symposium II: “When the tables had been removed and the guests had poured a libation and sung a hymn, there entered a man from Syracuse, to give them an evening's merriment. He had with him a fine flute-girl, a dancing-girl — one of those skilled in acrobatic tricks, — and a very handsome boy, who was expert at playing the cither and at dancing; the Syracusan made money by exhibiting their performances as a spectacle. They now played for the assemblage, the flute-girl on the flute, the boy on the cither; and it was agreed that both furnished capital amusement. Thereupon Socrates remarked: “On my word, Callias, you are giving us a perfect dinner; for not only have you set before us a feast that is above criticism, but you are also offering us very delightful sights and sounds.” “Suppose we go further,” said Callias, “and have some one bring us some perfume, so that we may dine in the midst of pleasant odours, also.” “No, indeed!” replied Socrates.”

In a letter to Ptolemaios, Demophon wrote (c. 245 B.C.): “Send us at your earliest opportunity the flutist Petoun with the Phrygian flutes, plus the other flutes. If it is necessary to pay him, do so, and we will reimburse you. Also, send us the eunuch Zenobius with a drum, cymbals, and castanets. The women need them for their festival. Be sure he is wearing his most elegant clothing. Get the special goat from Aristion and sent it to us. Send us also as many cheeses as you can, a new jug, and vegetables of all kinds, and fish if you have it. Your health! Throw in some policemen at the same time to accompany the boat.

Boscoreale fresco of a woman with a kithara

Strabo wrote in “Geographia” (c. A.D. 20): “A festival is celebrated every year at Acharaca; and at that time in particular those who celebrate the festival can see and hear concerning all these things; and at the festival, too, about noon, the boys and young men of the gymnasion, nude and anointed with oil, take out a bull and with haste run before him into the cave; and, when they arrive at the cave, the bull goes forward a short distance, falls, and breathes out his life. [Source: Strabo, The Geography of Strabo: Literally Translated, with Notes, translated by H. C. Hamilton, & W. Falconer, (London: H. G. Bohn, 1854-1857)

The Roman-era Greek orator Dio Chrysostom wrote (A.D. 110): “Some people attend the festival of the god out of curiousity, some for shows and contests, and many bring goods of all sorts for sale, the market folk, that is, some of whom display their crafts and manufactures while others make a show of some special learning — many, of works of tragedy or poetry, many, of prose works. Some draw worshipers from remote regions for religion's sake alone, as does the festival of Artemis at Ephesos, venerated not only in her home-city, but by Hellenes and barbarians.

Clementis Recognitiones wrote (c. A.D. 220): “Most men abandon themselves at festival time and holy days, and arrange for drinking and parties, and give themselves up wholly to pipes and flutes and different kinds of music and in every respect abandon themselves to drunkenness and indulgence.”

Ancient Greek Musical Instruments

The ancient Greeks used three main types of instruments: 1) strings such a lyres and harps; 2) winds, mostly flutes and pipes; and 3) percussion instruments such as drums, tambourines, bells, castanets and cymbals. Among the most common Greek musical instruments were turtle shell lyres with sinew strings and reed flutes carved from sycamore wood that were played with a leather strap around the musicians face to keep his cheeks from bulging out too far. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

Lyres were arguably the most important and widespread instrument in ancient Greece. They were commonly used by poets as they recited Homeric tales, were associated with Apollo and were used in the musical education of Greek youths. The Kithara were the most sophisticated instrument used by professionals. The “phorminx” was a primitive string instrument used by epic singers.

Among the many wind instruments the “ardos” (a double-reed instrument) was the most common. Often used in duets with a kithara, it figured prominently in many social and religious occasions, including processions, banquets, dramatic festivals, Dionysian gatherings and the Olympic games. At Dionysian festivals women played drums made of hollow cylinders with skin membranes stretched over the ends. Bells were widely used to keep rhythm during ceremonies and at dance lessons.

The earliest known pipe organ, called a hydraulis, was invented in the third century B.C. by a Greek engineer from Alexandria named Ctesibius. It employed falling water to produce a constant flow of air that was directed through different size tubes. Organs with piston pumps and wooden sliders that made sound in pipes were described in Hellenistic times. These instruments were widely used across the Roman Empire.

Metal wind instruments, or trumpets, were only used for military and religious purposes. They were usually made of bronze, with a bone mouthpiece, were of a longish shape, with a very broad mouth. Among other musical instruments in use among the Greeks we must mention tambourines, cymbals, and castanets, which were used in the worship of Dionysus and Cybele, and in dances of an orgiastic character; a girl, dancing to the sound of a flute, holds castanets in her hands. But, in spite of the frequency with which these instruments are represented on works of art, especially those which are connected with Dionysus, their use in daily life must have been very rare, except for the dancing girls who appeared at the symposia, and who marked the time of their motions with them. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Stringed Instruments in Ancient Greece

Apollo with a kithara The commonest instruments in ancient Greece in ordinary use were stringed. These were well suited for solo-playing as well as for accompanying songs, and the singer could accompany himself with them, which would have been impossible in the case of wind instruments. The stringed instruments used in Greece were all played by striking or thrumming, and not by means of a bow; in fact, it is a disputed point whether the ancients, and in particular the Egyptians, were at all acquainted with the bow; in any case we do not find it in classical antiquity. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Among the various kinds of stringed instruments which had either existed in Greece since the oldest times or been introduced from foreign countries, especially from the East or from Egypt, there were only two which were of special importance for educational and ordinary purposes. These were the lyre and the kithara, which were closely related to one another, and only distinguished by the effect of the sound.

The harp is the oldest stringed instrument known. It was popular in ancient Greece and played by the Druids. It was used by David when composing the psalms. Greeks played lyres (primitive harps with four to ten strings) and the Kithara (a lyre-like instrument with more strings). According to legend Hermes made these instruments from tortoiseshell a few hours after his birth and presented them to mankind as a gift.

The lyre was generally played sitting. This instrument, which was a light one, was held close to the left side, as we see in two images, and supported by the seat of the chair. The kithara was played standing, and it was therefore necessary, on account of the considerable weight of the instrument, to suspend it by a band over the shoulders. This band is seldom represented in works of art, but it must always be assumed to be there, since the mode in which the stringed instruments were played would not leave a hand free for holding it. Both lyre and kithara were played in such a manner that the strings were thrummed from without by the left hand, but struck from within by an instrument called plectrum, held in the right hand, and constructed of wood, ivory, or some half-precious stone. This plectrum was fastened by a string to the instrument . There were, however, exceptions to this mode of playing; thus, a woman apparently does not use the plectrum, but thrums the strings of the lyre with both hands, and at other times it seems as though the left hand and the plectrum, which was held in the right, were not used at the same time, but in turns. Thus, both teacher and pupil are only thrumming the instrument with their left hand, and leaving the plectrum at rest. The practical object of fastening the plectrum to the instrument was that it enabled the player at any moment to pass from the use of the plectrum to the fingers of the right hand, and vice versa. An hypothesis based on works of art, and apparently very plausible, has been made by Von Jan, who supposes that musicians, as a rule, accompanied their song with the play of the left hand, and only used the plectrum in the pauses.

Besides the lyres and kitharae, among which we must certainly include the Homeric Phorminx, of which we find various kinds but all with the same main features, there are several other stringed instruments, to which we can, as a rule, assign the ancient names with some certainty, though we find a very great number of designations for these instruments in different writers, and apparently most of them were introduced into Greece from the East and from Egypt. One of the safest identifications relates to a large, many-stringed instrument, of a shape which closely resembles our modern harp. This is played by the third woman in the center, and is also found elsewhere. We almost always find this instrument in the hands of women; they play it seated, resting the horizontal base on their laps, while the broader sounding-board which joins this at an angle, rests against the upper part of their body; they strike the short strings near them with the right hand, without a plectrum, and with the left hand the long strings which are further from them. The pictures sometimes show contrivances for tuning, shortening, or lengthening the strings; the number of strings varies. As the shape is usually triangular, we may probably assume that this instrument is the one called Trigonon. Possibly some of the examples may be instances of the Sambuca, since this, too, had a triangular form.

We also hear of many other stringed instruments, of which we know only the names, some with a small number of strings — three or four, others with a large number — thirty to forty; but we know little or nothing about their shape, and, therefore, will not enter into details concerning them, especially as their use must have been very rare as compared with that of the instruments already described. We must just mention the Barbiton, since it seems probable that an instrument which appears very often on ancient monuments, very narrow and long, with a sounding-board closely resembling the lyre, but smaller, and with a very few strings, which was played with the hand and the plectrum, may have been the barbiton which was popular at festive gatherings, and for accompanying love-songs.

Lyre of Ancient Greece

The lyre was the usual instrument of the amateur. Boys learned to play it at school, and gentlemen were expected to be able to accompany themselves upon it at symposia. Its sounding-board was made of the shell of a tortoise covered on one side with wood. The upright pieces, curved outward and in again toward the top, were sometimes made of the horns of animals. It had a yoke near the ends of the uprights, and a bridge on the sounding-board. The strings, of sheep’s guts or sinews, varied in number from three to eleven at different periods, but seven was the usual number in the fifth century. The plectron was generally used in playing both instruments. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

The lyre, according to a Greek legend, was an invention of Hermes, who constructed the first lyre out of a tortoise, which he used as a sounding-board, stretching cords across it. Even in later times tortoise-shells seem to have been actually used in the construction of lyres, and on works of art, especially vase pictures, we can plainly distinguish the markings of the tortoise on the outer side of the instrument. It must, however, have been more usual to construct the sounding-board of wood, and only adorn it externally with tortoise-shell or other decorative materials; the writers mention boxwood and ilex as the principal materials for lyres, as well as ivory, which last was probably used for decorative purposes. In the Homeric hymn to Hermes, in which the invention of the lyre by the god is described in detail, Hermes cuts little stems of reed, which he fastens into the shell in gridiron fashion and covers with ox-skin, and by this means obtains the necessary covering for the sounding-board.

In later times the proceeding was probably different, since the usual material for the sounding-board was undoubtedly wood, and the covering was, no doubt, made of wood also. But the shape of the sounding-board always remained the same; the outer side was a good deal raised, while the inner side on which the strings were attached was a level surface. Into this sounding-board two arms were fixed, which are almost always represented on Greek monuments as merely curved pieces of wood fastened on the inner side of the sounding-board; but the custom which in later times, especially in the Alexandrine and Roman periods, became very common, of not merely constructing these arms in the shape of horns, but even making them of real horns of chamois or gazelles, no doubt existed even in the ancient Greek period.

Harp player at a symposia

At their upper ends the two arms, which might be called horns, were fastened together by a cross-piece, called the yoke, which was usually constructed of hard wood, and on to this the strings, constructed of sheep-guts, were stretched. Of these the lyre usually had seven, all of equal length, which was also the case in the kithara. These strings, as we can clearly see in the lyres of the above-mentioned bowl, passed downwards over a bridge consisting of a piece of reed fixed on the flat covering of the sounding-board, and were then fastened singly, probably to a little square board, such as we see on the lyre hanging on the wall. Probably this little board could be taken out, and thus, if a string were to break, the injury could be easily repaired. Occasionally the strings were merely tied to the yoke; but, as this primitive method would make it impossible to tune them, we must assume that there was usually some other contrivance, though neither writers nor monuments give us sufficient information about it. On the lyres and also in other pictures of stringed instruments, we perceive at the upper ends of the strings, longish rolls which in other places are shaped more like rings or discs, and are probably set at an angle to the stretched strings.

One hypothesis infers, from ancient writers, after comparing similar contrivances in Nubian stringed instruments, that these rolls were constructed of thick skin or hide, taken from the backs of oxen or sheep; the strings were fastened into these adhesive covers and twisted along with them round the yoke of the lyre until they attained the right tune, and they were then fastened into their proper position by strongly pressing down these rolls of hide. Still, this rough mode of fastening which could only permit of very superficial tuning of the strings, does not appear very satisfactory; indeed, Von Jan himself calls attention to a far more artistic contrivance observed in some of the pictures which has not yet, however, been satisfactorily explained. There seems also to have been a third mode of fastening; sometimes the whole yoke was divided into as many little pulleys connected by pegs as there were strings, so that each string had, as it were, its own yoke, by the tightening of which it could be tuned without the other strings being affected. We have no further details about this construction.

Kithara

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The kithara, an instrument of the lyre family, had seven strings of equal length and a solidly built, wooden body, usually with a flat base. Strings of gut or sinew were stretched from a holder at the base of the instrument over a bridge to the crossbar that joined the two sidepieces. The musician (kitharode), who usually stood while playing, made music by stroking the plektron in his right hand across the strings, sounding all those not damped with his left fingers. [Source: Collete Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

During performances, the instrument rested against the musician's shoulder, and was supported by a sling that wrapped around the left wrist. The musician could regulate pitch by the tension and, perhaps, thickness of the strings. By the end of the seventh century B.C., the kithara found a major niche in Greek public performances. Although similar in form to the tortoiseshell Greek lyra, which any well-bred Greek citizen might play, the kithara with its large sound box was more suited for virtuoso display. It was generally a professional musician's instrument reserved for public concerts, choral performances, and competitions.\^/

“Strings of gut or sinew were stretched from a holder at the base of the instrument over a bridge to the crossbar that joined the two sidepieces.Very little is known of the precise sound of the kithara in performance. In general, our knowledge of Greek music comes from fragmentary musical scores, some remains of instruments (mostly reed-blown pipes), inscriptions, and depictions in Greek sculpture and vase painting. Nontechnical references in ancient literature, especially the works of poets and philosophers, shed some light on the practice of music, its social roles, and perceived aesthetic qualities. \^/

“Greek theoretical essays provide insight into the structure of ancient music, and a limited number of essays, most notably passages of Athenaeus and the pseudo-Plutarchan dialogue, De musica, describe the nature and history of musical practice. The kithara is known primarily from written sources and from images on black- and red-figure pottery, such as the amphora attributed to the Berlin Painter (56.171.38) in the Metropolitan's collection. Here, a musician in a long, slim garment accompanies himself on the kithara, his sash swaying with the rhythm of his song. He spreads the fingers of his left hand behind the strings of his instrument and prepares to strike them with the plektron, or pick, in his right hand. The muscles in his neck stretch as he throws back his head and opens his mouth to sing.” \^/

Wind Instruments in Ancient Greece

banquet

The Syrinx, or pan-pipe, was made of reeds arranged in graduated lengths, fastened together with cords and wax. It was especially the shepherd’s companion in his long, solitary days with his flocks. In one kind of syrinx all the reeds are of equal length, but in others varied from short to long. These were often seen in pictures, especially of Pan and other forest and field divinities. A little faun, which forms the pendant of a bracelet, is playing the syrinx. The Plagiaulos was similar to the modern Flûte traversière. It originated in Egypt. Various kinds flutes have been described to us.

The pipe seems never to have been used singly in Greece, but only as the double flute, as we see on so many representations, and, as a rule, the flutes are both of equal length. In order to facilitate the playing on two instruments at the same time or in quick succession, and perhaps also to prevent the escape of air, they often, though not always, made use of a cheek-piece round the mouth. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The bronze statue of a flute player, of which both sides are represented in two images, shows very plainly the mode in which this bandage was fastened by two leathern thongs passed round the head; we can also recognise it in the flute player, a vase painting which undoubtedly, as the pedestal on which he stands indicates, represents a flute player at a public contest; this is also suggested by his curious costume — the long festive robe and short jacket without sleeves.

Flutes in Ancient Greece

The ancient flute differed from the modern in being played at the end, and in having a vibrating reed as a mouthpiece. The tone was shrill. Flutes were always played in pairs, and a kind of bandage was often worn by the player to support their weight. Flute music had a very wide use. It accompanied the voice in solo or chorus, and the kithara at public contests; it was employed in the theatre at Athens and at Rome, and was used to guide and accompany the exercises of the palaistra. The flute furnished music for dancers, and in Rome it was played at funerals. Meals were served and work such as the kneading of bread in bakeries was done to its music. [Source: “The Daily Life of the Greeks and Romans”, Helen McClees Ph.D, Gilliss Press, 1924]

Flutes seem to have much in use in Boeotia and also in the rest of Greece than Athens, even among amateurs, and at all times was of great importance, especially for choruses and festive performances, for entertainments during meals, dancing, and other such occasions. The form of this instrument which is commonest on the monuments is the double flute. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The ancient flute differed in shape and use from that which bears the name at the present day, since the players did not blow into it at the side, but made use of a mouthpiece like that of a clarinet. This mouthpiece, which was usually of the same material as the flute proper, has an easily vibrating tongue cut in its upper part, which vibrates within the mouth, as the greater part of the mouthpiece is taken right into the mouth by the player. The principal part of the flute, the pipe, which is either of the same thickness throughout, or else somewhat widened at the lower end, was sometimes formed of a single piece and sometimes of several component parts. Various notes were produced by the holes of which there were at first only three or four, but afterwards a larger number; there were also holes at the side, which helped to increase the compass of the flute, and various other helps, such as valves on the side, rings which in turning either opened or closed the holes, etc. In spite of the very numerous practical attempts instituted during the present century to procure some notion of the mode of playing and the effect of the ancient flute, it does not seem possible to obtain any proper conception of it.

In a vase painting a flute player, who accompanies the gymnastic exercises, is also playing the double flute with the mouth bandage; over his arm hangs the flute case, which was usually made of skin, and with which the case for the mouthpieces, of which they had several, was connected. On the other hand, the youth has no bandage; nor yet the two women, or the seated hetaera, nor the youth who in a vase painting represented, with a double flute in his hand, mounts the pedestal from which he intends to perform to the audience who are seated close by. On the Greek monuments of the pre-Roman period we always find two similar flutes connected together, but afterwards, and especially in pictures connected with the worship of Cybele, one of the flutes very often has a curved horn, which seems to have been a special peculiarity of the Phrygian flute. This was apparently not known to the Greeks in ancient times.

Music Instruction in Ancient Greek Schools

The instruction in these elementary subjects occupied the first years of school life. In the twelfth or thirteenth year the instruction in music began, and was given by a special master called the harpist, the Greeks regarding music not from the standpoint of the modern amateur, as only a pleasant distraction for hours of recreation, but rather as an essential means of ethical development. The main object of the instruction was not the attainment of facility in execution on any instrument, but rather ability to render as well as possible the productions of the poets, especially the lyrists, and at the same time to accompany themselves suitably on a seven-stringed instrument. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Accordingly, most weight was given to the instruction in the lyre (which we see in one image in the hand of both teacher and pupil), while the kithara, on account of its louder sounding-board, as well as the phorminx, which was connected with it, if not, in fact, identical, were reserved for the use of professionals, and were regarded as a kind of concert instrument, and therefore learned specially by those who desired to attain something more than average proficiency in music. No doubt there was opportunity given in the ordinary schools for learning both kinds of stringed instrument. The flute, which, when used for purposes of accompaniment, could naturally not be played by the singer, was on this account less popular at Athens; at Thebes, on the other hand, it was universally popular, and it has been supposed that the neglect of the flute at Athens was due to the ancient antagonism between Attica and Boeotia; moreover, the flute, which originally belonged to the Bacchic worship of Asia Minor, with its sharp, shrill tone, was regarded as an exciting instrument, hostile to a calm state of mind, and therefore the philosophers all agreed in considering it unsuitable from a pedagogic point of view. We must not forget that the Greek flute was very different from that to which we give the name at the present day, which is regarded as a somewhat sentimental, effeminate instrument.

There was, however, a time when flute-playing was popular at Athens among amateurs; according to Aristotle, the flute was introduced into Attic schools after the time of the Persian Wars, and soon became so popular that almost all the youths of the better classes learnt to play on it. Afterwards, however, apparently about the time of the Peloponnesian War, they recognised how very unsuitable this instrument was for intellectual and musical development, and it was again discarded by people of culture, probably in consequence of the example set by Alcibiades, who was regarded as a leader of fashion. Afterwards the flute was still learnt, and on vase pictures we see flutists and hetaerae playing it, as well as youths, but it was no longer a subject of instruction in the ordinary schools — at any rate, not at Athens. Naturally Sparta carefully avoided an instrument which was regarded as absolutely dangerous in its ethical effect. No musical instruction, besides the elementary subjects and playing on stringed instruments and singing, was given at school during the best period of Athens.

Music and Songs at a Symposia

As a rule, music played an important part at the symposia. Even in the Homeric period, song was an important feature of the banquet. The cunning singer, who sang the stories of gods and heroes to the accompaniment of the “lyre,” and who was listened to eagerly by all, was never absent from any banquet at which a great number of guests were present. In historic times, the musical entertainment took a different character, for the guests, instead of merely listening, took part in it themselves, singing generally as well as playing. There were three kinds of singing; choruses, sung by all together, such as the Paean already mentioned; part songs, in which all shared, not together, but each in his turn; and solos, sung by those who had special musical ability and education. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

These solos were especially popular; the singer accompanied himself with the harp, and here, too, they adhered to the custom of always passing to the right the harp and the myrtle bough, which the singer had to hold in his hand during the performance. Of especial importance among these solo songs, from a literary point of view, were the “Scolia,” which were usually of a serious character, either religious, patriotic, or of a general moral nature. A well-known scolion sang the praises of the two conspirators who murdered the tyrant Hipparchus; it began as follows:

“In myrtle veiled, I will the falchion wear;

For thus the patriot sword

Harmodius and Aristogeiton bare,

When they the tyrant’s bosom gored;

And bade the men of Athens be

Regenerate in equality.

Beloved Harmodius, oh, never

Shall death be thine, who livest for ever.

Thy shade, as men have told, inherits

The islands of the blessed spirits,

Where deathless live the glorious dead,

Achilles, fleet of foot, and Diomed.”

Other songs celebrated the praise of wine, the joys of love, the happiness of friendship; there were also special drinking songs, some composed by very great poets, such as Alcaeus, Sappho, Anacreon, Simonides, Pindar, who composed them in various meters. A vase painting shows us a reveller lying on a couch with a wreath on his head, holding a lyre in his hand, and singing, while raising his head as though inspired; the words written underneath by the vase painter show us that he is singing an ode by Theognis in praise of a beautiful boy. Here, too, changes in taste took place in the course of time; many of the old songs were regarded as old-fashioned, even in the time of Aristophanes, and he who when his turn came sang a song by Simonides, instead of some grand air from Euripides, was regarded as quite behind the times.

See Separate Article: SYMPOSIUM IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Delphic Hymn to Apollo

This hymn to Apollo, god both of the Delphic Oracle and of music, was found inscribed on a stone at Delphi. The text is marked with a form of music notation which makes it one of the earliest pieces of music to have survived in the western world. We have no way of determining exactly how the piece would have been performed, but recordings have been made which may convey something of the sound of the work. One version is available on the album “Music of Ancient Greece,” Orata ORANGM 2013 (track 3), and another on “Musique de la Grèce Antique” Harmonia Mundi (France) HMA 1901015 (track 24). Here is a translation of the first part of the Paean.

Apollo

Oh, come now, Muses, (1)

and go to the craggy sacred place

upon the far-seen, twin-peaked Parnassus, (2)

celebrated and dear to us, Pierian maidens. (3)

Repose on the snow-clad mountain top;

celebrate the Pythian Lord (4)

with the goldensword, Phoebus,

whom Leto bore unassisted (5)

on the Delian rock (6) surrounded by silvery olives,

the luxuriant plant

which the Goddess Pallas (7)

long ago brought forth.

[Source: translated by Richard Hooker]

Notes: (1) The muses were the goddesses of the arts, the word “music” comes from their name. (2) Mount Parnassus was the site of the temple of the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi, the most sacred spot in Greece. (3) The muses were also associated with a place called Pieria near Mount Olympus; but another explanation of the reference is that they were said to be the nine daughters of one Pierus. (4) Apollo. His priestess was called the Pythia, after a legendary snake that Apollo had killed in laying claim to the shrine. (5) There are many different accounts of how Apollo’s mother wandered the earth looking for a safe place in which to bear her child. (6) The island of Delos. (7) Athena. Note how the Athenian poet, even while praising the chief god of Delphi manages to bring in by a loose association the chief goddess of Athens.

See Separate Article: HOMER: HIS WORKS, HYMNS AND STYLE europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024