Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

LEISURE TIME IN ANCIENT ROME

On days when no spectacles or shows were provided, the Roman filled up the time until supper with strolling or gambling, exercise, or a bath at the thermae. In the shadow of their colonnades the idle Romans loafed or gathered to gossip. They ogled the passers-by, both men and women. When a sale was being held in the saepta, they leisurely attended, assessed the value of the objects offered, and haggled over the price. Everywhere they eagerly inquired the latest news, and everywhere they found some boastful busybody ready to satisfy their curiosity. Martial vividly describes such a braggart who invents as he goes along the "secrets' with which he regales his auditors: By such arts as these, Philomusus, you always earn your dinner; you invent much and retail it as truth. You know what counsel Pacorus, king of Parthia, takes in his Arsacian palace; you estimate the Rhenish and Sarmatian armies... you know how many ships set sail from Libya's Shores... for whom Capitoline Jupiter designs his chaplets.

On days when no spectacles or shows were provided, the Roman filled up the time until supper with strolling or gambling, exercise, or a bath at the thermae. In the shadow of their colonnades the idle Romans loafed or gathered to gossip. They ogled the passers-by, both men and women. When a sale was being held in the saepta, they leisurely attended, assessed the value of the objects offered, and haggled over the price. Everywhere they eagerly inquired the latest news, and everywhere they found some boastful busybody ready to satisfy their curiosity. Martial vividly describes such a braggart who invents as he goes along the "secrets' with which he regales his auditors: By such arts as these, Philomusus, you always earn your dinner; you invent much and retail it as truth. You know what counsel Pacorus, king of Parthia, takes in his Arsacian palace; you estimate the Rhenish and Sarmatian armies... you know how many ships set sail from Libya's Shores... for whom Capitoline Jupiter designs his chaplets.

If his aim was to escape the hurly-burly of the streets, the Roman had only to seek the quiet regions which were the "promenades" of the city: the fora and the basilicas, when once the judicial hearings were over; the gardens belonging to the emperors, which were left open to the public, even though they were not all, like Caesar's, bequeathed to the people. These he sought out "when on the threshold of the city so rich was the beauty of spring and the charm of fragrant Flora, so rich the glory of Paestan fields; so ruddy, where'er he turned his footsteps, or his eyes, was every path with twining roses." And the Campus Martius with its marble enclosures (the Saepta lulia), its sacred halls and porticos, provided a shelter from the sun, a refuge from the rain, and in all weathers, as Seneca puts it, "a place where the most wretched could take his ease: cum vilissimus quisque in campo otium suum oblcctet"

We still possess the entrance to one of these porticos which Augustus dedicated in the name of his sister Octavia and which enclosed within its marble columns a space 118 by 135 meters containing the twin temples of Jupiter and Juno. But there were many other porticos to the north, and Martial mentions some of them in describing the route taken by the parasite Selius in quest of a friend who might be induced to ask him to dinner: the Portico of Europa, the Portico of the Argonauts, the Portico of a Hundred Pillars with its alley of plantains, the Portico of Pompey with its two groves. These saepta were not only set amid refreshing shade and grass, but filled with works of art: frescos covered their inner walls, statues adorned the spaces between their columns and their interior courts. In the Portico of Octavia alone Pliny the Elder enumerates, apart from a certain number of command pieces executed by Pasiteles and his pupfil Dionysius, the group of Alexander and his generals at the battle of the Granicus by Lysippus, a Venus of Phidias, a Venus of Praxiteles, and the Cupid which Praxiteles had destined for the town of Thespiae.

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology Magazine: At a housing development site in North Yorkshire, England, archaeologists have unearthed a sprawling Roman building complex dating to between the second and fourth centuries A.D. In addition to a bathhouse, the complex included at its center an unusual circular structure with four square rooms branching off it. Similar Roman buildings are known from North Africa and Portugal, says Historic England archaeologist Keith Emerick, but this architectural layout is unique in Roman Britain. The researchers think the complex was either a luxurious Roman villa or a religious sanctuary — or perhaps a hybrid. “Another interpretation of the site is a kind of gentlemen’s club,” Emerick says. “A modern equivalent would be a high-status leisure hotel that serves a number of functions, like a spa and sauna.” [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2021

RELATED ARTICLES:

GAMES AND GAMBLING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

BATHING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

BATHS IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, TYPES, PARTS factsanddetails.com

PUBLIC GAMES AND SHOWS OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN CHARIOT RACING: HISTORY, TEAMS, FANS, HORSES AND FAME europe.factsanddetails.com

CIRCUSES — WHERE ROMAN CHARIOT europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN SPORT: BALL GAMES AND FIXED WRESTLING MATCHES europe.factsanddetails.com

PETS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Leisure and Ancient Rome” by J. P. Toner (1998) Amazon.com;

“Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero: The Villas of Oplontis Near Pompeii” by Elaine K. Gazda, John R. Clarke , et al. (2016) Amazon.com;

“Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome” by J.P.V.D. Balsdon (1969) Amazon.com;

“Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome” by George Jennison (1937) Amazon.com;

“On Leisure “ by Seneca , translated by Frank Miller Amazon.com;

“Arts, Leisure and Entertainment: Life of the Ancient Romans” by Don Nardo (2003) Amazon.com;

“Popular Culture in Ancient Rome” by Jerry Toner (2013) Amazon.com;

“Roman Gardens” by Anthony Beeson (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Sports, A-Z: Athletes, Venues, Events and Terms” by David Matz Amazon.com;

“Beyond the Coliseum Sporting Culture in Ancient Rome”, Kindle Edition,

by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“The Roman Games: A Sourcebook (Blackwell) by Alison Futrell Amazon.com;

“Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Sourcebook” by Anne Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Donald G. Kyle Amazon.com;

“Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire” by Fik Meijer, Liz Waters (2010) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Day Commodus Killed a Rhino: Understanding the Roman Games” (Witness to Ancient History) by Jerry Toner (2015) Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Circuses and Public Games in Ancient Rome

Roman circuses were held in outdoor arenas such as the Circus Maximus (meaning “Biggest Circus”) in Rome. In addition to gladiator contests there were often displays of acrobatics, wrestling and horsemanship. During the gladiator battles, musicians played water organs and metal horns that looped around their heads. Some arenas could be flooded with water for mock sea battles and then emptied for mock hunts.

Circus Maximus (on the side of the Palatine Hill opposite the Forum) is the large oval grass track where chariot races, athletic competitions and mock naval battles were held. Built in 600 B.C. and large enough, according to some reports, to accommodate 300,000 people, today it resembles a cross between a big ditch and a modern athletic field. If you know where to look you can find the start and finish lines.

By some estimates 200,000 people showed up to watch chariot races at the Circus Maximus in Rome. The games of the circus were the oldest of the free exhibitions at Rome and always the most popular. The word circus means simply a “ring”; the ludi circenses were, therefore, any shows that might be given in a ring.” The circus is associated mostly closely with chariot races. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The circus was used less frequently for exhibitions other than chariot races. Of these may be mentioned the performances of the desultores, men who rode two horses and leaped from one to the other while they were going at full speed, and of trained horses that performed various tricks while standing on a sort of wheeled platform which gave a very unstable footing. There were also exhibitions of horsemanship by citizens of good standing, riding under leaders in squadrons, to show the evolutions of the cavalry. The ludus Troiae was also performed by young men of the nobility; this game is described in the Aeneid, Book V. More to the taste of the crowd were the hunts (venationes); wild beasts were turned loose in the circus to slaughter one another or be slaughtered by men trained for the purpose. We read of panthers, bears, bulls, lions, elephants, hippopotamuses, and even crocodiles (in artificial lakes made in the arena) exhibited during the Republic. In the circus, too, combats of gladiators sometimes took place, but these were more frequently held in the amphitheater. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“One of the most brilliant spectacles must have been the procession (pompa circensis) which formally opened some of the public games. It started from the Capitol and wound its way down to the Circus Maximus, entering by the porta pompae (named from it), and passed entirely around the arena. At the head in a car rode the presiding magistrate, wearing the garb of a triumphant general and attended by a slave who held a wreath of gold over his head. Next came a crowd of notables on horseback and on foot, then the chariots and horsemen who were to take part in the games. Then followed priests, arranged by their colleges, and bearers of incense and of the instruments used in sacrifices, and statues of deities on low cars drawn by mules, horses, or elephants, or else carried on litters (fercula) on the shoulders of men. Bands of musicians headed each division of the procession. A feeble reminiscence of all this is seen in the parade through the streets that for many years has preceded the performance of the modern circus. |+|

Sculptures and paintings indicate the ancient Greeks and Romans played games similar to rolling bowls or hoops. There have been some suggestions that the modern game of lawn bowls evolved from a game played on Roman-era Britain in the A.D. 5th century.

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Parties in Ancient Rome

pyrric dance A convivium was a dinner party with family, friends or associates. It was somewhat like a Greek symposium except that it was generally regarded as a chance to talk business or politics rather than philosophy and weighty matters. A commissatio was a wild drinking party. One graffiti inscription from Rome reads: "Let's eat, drink, have fun; first comes life, then philosophy."

Prostitutes, jugglers, musicians, acrobats, actors and fire-eaters entertained guests at banquets Wealthy Romans were entertained by freak shows with midgets, and handicapped and deformed people, some of whom performed sexual feats for dinner guests. Lamprey milt was served on an eel-shaped tray. Rose petals were scattered on the floor. Mechanical devices lowered acrobats and entertainers from the ceiling. Slaves blew exotic scents into the room.

Nero and his advisors were famous for their lavish parties. Tacitus wrote: "Nero...gave feasts in public places as if the whole city were his own home. But the most prodigal and notorious banquet was given by Tigellinus [Nero's advisor]...The entertainment took place on a raft constructed on Marcus Agrippa's lake. It was towed above other vessels, with gold and ivory fittings. Their rowers were degenerates, assorted according to age and vice.On the quays were brothels stocked with high-ranking ladies. Opposite them could be seen naked prostitutes, indecently posturing and gesturing...At nightfall the woods and houses nearby echoed with singing and blazed with lights. Nero was already corrupted by every lust, natural and unnatural."

"A few days later he went through a formal wedding ceremony with one of the perverted gang called Pythagoras. The emperor, in the presence of witnesses, put on the bridal veil. Bowery, marriage bed, wedding torches, all were there. Indeed, everything was public." Nero had three wives. One wife is said to have bathed in donkey milk scented with rose oil.

See Separate Article: BANQUETING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Tourism, Inns and Taverns in Ancient Rome

Tourism developed under Augustus during the Pax Romana. Young wealthy tourists visited Greece, Asia Minor and Egypt. The roads and seas were safe for travel and people visited famous temples, places from the Iliad and Alexander' conquest, and even went to the Pyramids. Roman tourists bought souvenirs such as miniature copies of temples or statues made of pottery, glass, bronze, silver and stone. They also left inscribed their names on the walls of tombs and ruins. At the Temple of Isis one man even wrote "I, L. Trebonius Oricula was here."

In the Roman Empire there were inns (cauponae) and taverns (popinae and tkermopolia), whose front counters served cooling draughts or hot wine, concealed in their back premises gambling dens where year in and year out, not only during the Saturnalia, bets could be exchanged and dice and knuckle-bones rattled. The imperial laws which bore as hard on gamblers (aleatores) as on thieves could not reach out an arm long enough to catch the susceptor, the keeper of the den who sheltered them; the most the law could do was to deny him the right to sue for any violence done him or the furnishings of his tavern by clients in the excitement of their gaming or despair at their losses. With this relative impunity, the keeper was all the more tempted to equip his shop for seductive, forbidden parties, and by installing prostitutes as barmaids, to convert his gambling den into a bawdy-house. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

A frequently quoted inscription from Aesernia tells of a passing traveller who, settling with the hostess of the local inn, acquiesces in an item of eight asses (about twelve cents) charged for the favors accorded him by the maid-servant during his one-night stay. We might also cite the popina, recently unearthed in the Via delP Abbondanza at Pompeii, which bears a suggestive poster notifying the passer-by that the establishment boasts three young ladies (asellae) on its staff. It would be an illusion to imagine that Rome itself was in any way behind the Italian muncipia in such conveniences.

There, as elsewhere, the cauponae, the popinae, and the thermopolia were currently equated with "dives" (ganeae) and while the authorities out of consideration for the young Roman's morning exercise decreed that brothels should remain closed until the ninth hour, the Roman tavern offered its attractions to every comer both morning and afternoon. The shady bar was perhaps not quite so omnipresent in Rome as in modern capitals, but it was common, winked at by the aedile police, and freely open to passers-by. Seneca records how many wastrels turned into these dens instead of finding their way to the palaestra to spend their leisure: "Cum illo tempore vilissimus quisque... in popina lateat"

Taking a Stroll in the Ancient City of Rome

At first sight the crowded streets of Imperial Rome might seem ill suited for walking. The pedestrian was hampered by the outspread stalls of "audacious hucksters," jostled by passers-by, spattered by riders on horseback; harassed by "hoarse-throated beggars" who stationed themselves along the slopes, under the arcades, and on the bridges; trampled by the military who held the middle of the road and advanced as if marching in conquered territory, planting the hobnails of their boots on the foot of any civilian rash enough not to have made way for them. But this never-ending and motley crowd was interesting in itself.

The flow of traffic which bore the Roman along bore with him all the nations of the habitable globe: "the farmer of Rhodope... the Sarmatian fed on draughts of horse's blood, the Egyptian who quaffs at its spring the stream of first-found Nile... the Arab, the Sabaean, the Cilician, drenched in his own saffron dew... the Sygambrian with knotted hair, the Ethiopian with locks twined otherwise"; and even if he had no use for their cheap-Jack wares, the "tramping hawker's" readiness of tongue delighted him, and so did the conjurors and snake charmers with their uncanny skill. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The general prohibition against carriages held good by day, but if he had the good luck to be mounted he could enjoy this welter of activity without being inconvenienced by it. He might prance along on his own mule or one lent him by the kindness of a friend or hired from a Numidian muleteer, part of whose duty was to lead it by the bridle. Or he might prefer to loll in the depths of an immense litter (lectica), panelled with "transparent stone" through which he could see without being seen as his six or eight Syrian porters cut their way through the crowd. He might be borne in a carrying chair (sella), such as matrons were wont to use for paying calls ; in this he could read or write as he went along. Or again he might be content with a sort of wheelbarrow (chiromaxium) like the one Trimalchio had presented to his favorite.

The walks of the imperial people were indeed set amid prodigious collections of booty. But among the Romans who stopped to contemplate these masterpieces, there were some who sought only to draw amusement from the familiar rarities. Martial tells an illuminating little anecdote. Among other statues of wild beasts in the Portico of a Hundred Pillars stood a bronze bear, which one day attracted the attention of the idlers: "While Hylas was in play challenging its yawning mouth he plunged his youthful hand into its throat. But an accursed viper lay hid in the dark cavern of the bronze, alive with a life more deadly than that of the beast itself. The boy perceived not the guile, until he felt the pang and died." This was the folly of a mischievous lad, but we shall see that it was not only boys who played under the porticos, in the gardens, the fora, and the basilicas.

Family Recreation in Ancient Rome

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “Downtime was a big part of Roman family life. Usually, starting at noon, the upper crust of society dedicated their day to leisure. Most enjoyable activities were public and shared by rich and poor alike, male and female—watching gladiators disembowel each other, cheering chariot races, or attending the theatre. [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016]

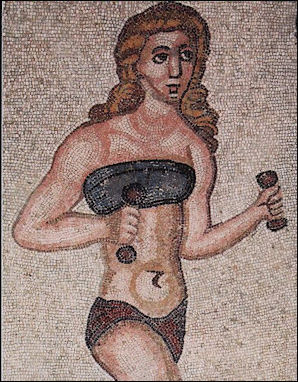

“Citizens also spent a lot of time at public baths, which wasn’t your average tub and towel affair. A Roman bath typically had a gym, pool, and a health center. Certain locales even offered prostitutes. Children had their own favorite pastimes. Boys preferred to be more active, wrestling, flying kites, or playing war games. Girls occupied themselves with things like dolls and board games. Families also enjoyed just relaxing with each other and their pets.

The Romans loved their bathes and much of Roman social life centered around them. Bathing was both a social duty and a way to relax. During the early days of Roman baths there were no rules about nudity or the mixing of the sexes, or for that matter rules about what people did when they were nude and mixing. For women who had problems with this arrangement there were special baths for women only. But eventually the outcry against promiscuous behavior in the baths forced Emperor Hadrian to separate the sexes. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Most Roman houses, large or small, had a garden. Large homes had one in the courtyard and this was often where the family gathered, socialized and ate their meals. The sunny Mediterranean climate in Italy was usually accommodating to this routine. On the walls of the houses around the garden were paintings of more plants and flowers as well as exotic birds, cows, birdfeeders, and columns, as if the homeowner was trying achieve the same affects as the backdrop on a Hollywood set. Poor families tended small plots in the back of the house, or at least had some potted plants.

Leisure Time and Family Visits at Vindolanda

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “Life on the north-west frontier was clearly less than exciting for the officer classes. Cerialis writes to Brocchus in another letter asking for some hunting nets: 'and please make sure that they are repaired strongly'. Brocchus was the commander of a nearby fort called Briga (Celtic for 'hill'), which we cannot identify. His wife, Claudia Severa, was in regular correspondence with Cerialis' wife, Sulpicia Lepidina.: [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, November 16, 2012 |::|]

The most famous of these is the well-known birthday invitation.’Claudia Severa to her Lepidina greetings. On the third day before the Ides of September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present(?). Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send him(?) their greetings. I shall expect you sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail.’. (Tab. Vindol. II.291)

“In fact, the officer classes seem to have been engaged in a constant round of visits. Another letter from Claudia Severa informs Lepidina that Brocchus will always let her come to Vindolanda to visit whenever she can, while several accounts by the household slaves indicate that Brocchus had donated tunics to the Cerialis household in the past, and in return had dined on several occasions, both with and without his friend Niger, on which occasions chickens were slaughtered. Finally, a cryptic line at the end of one list of accounts informs us that on 25 June: 'The lords have remained at Briga'. |::|

children's games

“On a more personal note, a certain Velde(d)ius, who had secured a promotion to act as groom of the governor down in London, visited his 'brother and old messmate' Chrauttius en route to Housesteads. He probably stayed in the mansio, since he was on official business of some sort, and may have dropped off the shears which Chrauttius had asked him to get for him in the letter, which he discarded whilst he was there. He also left behind a leather offcut with his name inscribed upon it, and may have owned the magnificent chamfron which was found nearby. The two of them probably exchanged news about their 'sister', Thuttena, and various old messmates whom Chrauttius had mentioned in his letter. Veldedius then went on to Housesteads, where he died in unknown circumstances and an official tombstone was erected, with his name slightly mis-spelled, though it is still likely to have been the same man.” (Tab. Vindol. II.310). |::|

Romans and Caledonians Drank Together as a Pub in Northern Britain

In 2012, archaeologists surveying the world’s most northerly Roman fort announced they had found an ancient pub there. George Mair wrote in The Scotsman: “The discovery, outside the walls of the fort at Stracathro, near Brechin, Angus, could challenge the long-held assumption that Caledonian tribes would never have rubbed shoulders with the Roman invaders. Indeed, it lends support to the existence of a more complicated and convivial relationship than previously envisaged, akin to that enjoyed with his patrician masters by the wine-swilling slave Lurcio, played by comedy legend Frankie Howerd, in the classic late 1970s television show Up Pompeii!. [Source: George Mair, scotsman.com, September 8, 2012]

“Stracathro Fort was at the end of the Gask Ridge, a line of forts and watchtowers stretching from Doune, near Stirling. The system is thought to be the earliest Roman land frontier, built around AD70 – 50 years before Hadrian’s Wall. The fort was discovered from aerial photographs taken in 1957, which showed evidence of defensive towers and protective ditches. A bronze coin and a shard of pottery were found, but until now little more has been known about the site. The archaeologists discovered the settlement and pub using a combination of magnetometry and geophysics without disturbing the site and determined the perimeter of the fort, which faced north-south.

“Now archaeologists working on “The Roman Gask Project” have found a settlement outside the fort – including the pub or wine bar. The Roman hostelry had a large square room – the equivalent of a public bar – and fronted on to a paved area, akin to a modern beer garden. The archaeologists also found the spout of a wine jug. Dr Birgitta Hoffmann, co-director of the project, said: “Roman forts south of the Border have civilian settlements that provided everything they needed, from male and female companionship to shops, pubs and bath houses.

““It was a very handy service, but it was always taught that you didn’t have to look for settlements at forts in Scotland because it was too dangerous – civilians didn’t want to live too close.“But we found a structure we think could be identifiable as the Roman equivalent of a pub. It has a large square room which seems to be fronting on to an unpaved path, with a rectangular area of paving nearby. We found a piece of highquality, black, shiny pottery imported from the Rhineland, which was once the pouring part of a wine jug. It means someone there had a lot of money. They probably came from the Rhineland or somewhere around Gaul.” We hadn’t expected to find a pub. It shows the Romans and the local population got on better than we thought. People would have known that if you stole Roman cattle, the punishment would be severe, but if they stuck to their rules then people could become rich working with the Romans.”

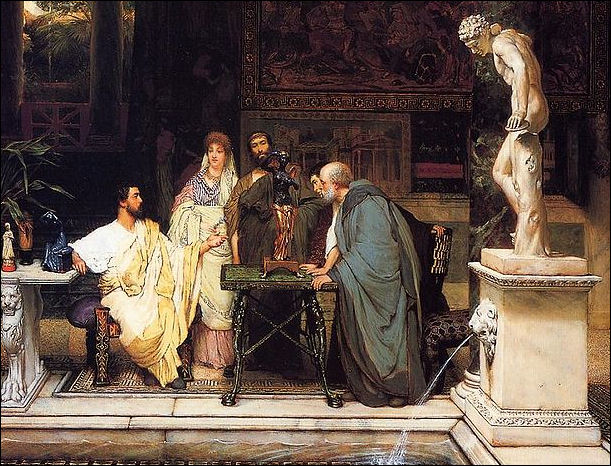

Getty villa, a copy of the House of Papyri at Herculaneum

Gardens in Ancient Rome

Most Roman houses, large or small, had a garden. Large homes had one in the courtyard and this was often where the family gathered, socialized and ate their meals. The sunny Mediterranean climate in Italy was usually accommodating to this routine. On the walls of the houses around the garden were paintings of more plants and flowers as well as exotic birds, cows, birdfeeders, and columns, as if the homeowner was trying achieve the same affects as the backdrop on a Hollywood set. Poor families tended small plots in the back of the house, or at least had some potted plants.

A peristyle garden was surrounded by a colonnade. A pool or fountain often sat at the center and space was filled with a variety of sculptures and plants. These gardens were designed be oases of green in an otherwise urban landscape. Those that could afford it decorated their gardens with busts of gods or philosophers and animal statuary. Relief ornaments called oscilas were suspended from space between columns so, as their name suggests, they could oscillate in the breeze. Some large gardens were built by wealthy Romans to display their wealth.

In Pompeii, archaeologists have reproduced Roman gardens with the same plants found in classical times. Opium was sometimes grown in Roman gardens.

The Romans were obsessed with roses. Rose water bathes were available in public baths and roses were tossed in the air during ceremonies and funerals. Theater-goers sat under awning scented with rose perfume; people ate rose pudding, concocted love potions with rose oil, and stuffed their pillows with rose petals. Rose petals were a common feature of orgies and a holiday, Rosalia, was name in honor of the flower.

Nero bathed in rose oil wine. He once spent 4 million sesterces (the equivalent of $200,000 in today's money) on rose oils, rose water, and rose petals for himself and his guests for a single evening. At parties he installed silver pipes under each plate to release the scent of roses in the direction of guests and installed a ceiling that opened up and showered guests with flower petals and perfume. According to some sources, more perfumes was splashed around than were produced in Arabia in a year at his funeral in A.D. 65. Even the processionary mules were scented.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024