Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

ANCIENT ROMAN CIRCUSES

For the Romans a circus was a spectacles for large crowds with gladiator battles and other events .Roman circuses were held in outdoor arenas such as the Circus Maximus (meaning “Biggest Circus”) in Rome. In addition to gladiator contests there were often displays of acrobatics, wrestling and horsemanship. During the gladiator battles, musicians played water organs and metal horns that looped around their heads. Some arenas could be flooded with water for mock sea battles and then emptied for mock hunts.

Circuses were essentially elaborate hippodromes, which is what the Greeks called the places where horse races and chariot races were held. Built in 330 B.C. the Hippodrome in what is now Istanbul was the largest stadium in the ancient world. Horse races and gladiator vs. animal battles were held here in front crowds so rowdy they make British soccer hooligans look like saints. During one event in A.D 532 that turned into an angry political rally against Emperor Justinian, the Byzantine army massacred 30,000 people. All sporting events were cancelled for a few years after that but when they resumed, chariot races continued for another 500 years.

The second circus to be built at Rome was the Circus Flaminius, erected in 221 B.C. by the Caius Flaminius who built the Flaminian Road. It was located in the southern part of the Campus Martius, and like the Circus Maximus, was exposed to the frequent overflows of the Tiber. Its position is fixed beyond question—it was near the Capitoline Hill—but the actual remains are very scanty, so that little is known of its size or appearance. The third to be established was erected in the first century A.D. It was named after Caius (Caligula) and Nero, the two emperors who had to do with its construction. It lay at the foot of the Vatican Hill, where St. Peter’s now stands, but we know little more of it than that it was the smallest of the three. These three were the only circuses within the city. In the immediate neighborhood, however, were three others. Five miles out on the Via Portuensis was the Circus of the Arval Brethren. About three miles out on the Appian Way was the Circus of Maxentius, erected in 309 A.D. The Circus of Maxentius is the best preserved of all; a restoration and a plan of it are shown in Figures 208 and 209, respectively. On the same road, some twelve miles from the city, in the old town of Bovillae, was a third, making six within easy reach of the people of Rome. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

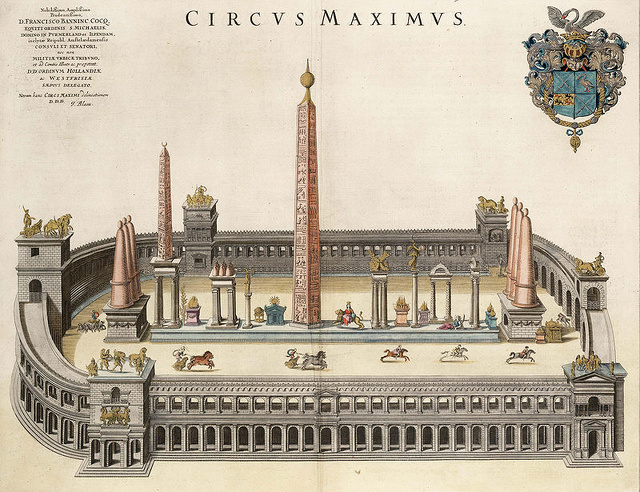

“A representation of a circus has been preserved to us in a board-game of some sort found at Bovillae, which gives an excellent idea of the spina. We know from various reliefs and mosaics that the spina of the Circus Maximus was covered with a series of statues and ornamental structures, such as obelisks, small temples or shrines, columns surmounted by statues, altars, trophies, and fountains. Augustus was the first to erect an obelisk in the Circus Maximus; it was restored in 1589 A.D., and now stands in the Piazza del Popolo; without the base it measures about seventy-eight feet in height. Constantius erected another in the same circus, which now stands before the Lateran Church; it is 105 feet high. The obelisk of the Circus of Maxentius now stands in the Piazza Navona. Besides these purely ornamental features, every circus had on each end of its spina a pedestal, one supporting seven large eggs (ova) of marble, the other seven dolphins. One of each was taken down at the end of each lap, in order that the people might know just how many laps remained to be run. Another and very different idea for the spina is shown in a mosaic at Lyons. This is a canal filled with water, with an obelisk in the middle. The metae in their developed form are shown very clearly in this mosaic, three conical pillars of stone set on a semicircular plinth, all of the most massive construction. |+|

RELATED ARTICLES:

ROMAN CHARIOT RACING: HISTORY, TEAMS, FANS, HORSES AND FAME europe.factsanddetails.com

CHARIOT RACING AND HORSE RACING IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT ROMAN SPORT: BALL GAMES AND FIXED WRESTLING MATCHES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECREATION IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

GAMES AND GAMBLING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

PUBLIC GAMES AND SHOWS OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS europe.factsanddetails.com

NAUMACHIAE — GIANT ROMAN ST europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire” by Fik Meijer, Liz Waters (2010) Amazon.com;

“Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing” by John H. Humphrey Amazon.com;

“Chasing Chariots: Proceedings of the First International Chariot Conference” (Cairo 2012)

by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer and Prof. Dr. Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age War Chariots” Illustrated (2006) by Nic Fields Amazon.com;

“Ben-Hur: 50th Anniversary Edition” (DVD) (originally released 1959)

Amazon.com;

“Ancient Roman Sports, A-Z: Athletes, Venues, Events and Terms” by David Matz Amazon.com;

“The Victor's Crown: A History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium”

by David Potter Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Games: A Sourcebook (Blackwell) by Alison Futrell Amazon.com;

“Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Sourcebook” by Anne Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Donald G. Kyle Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Day Commodus Killed a Rhino: Understanding the Roman Games” (Witness to Ancient History) by Jerry Toner (2015) Amazon.com;

“Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome” by J.P.V.D. Balsdon (1969) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Circus Maximus

Circus Maximus (on the side of the Palatine Hill opposite the Forum) is the large oval grass track where chariot races, athletic competitions and mock naval battles were held. Built in 600 B.C. and large enough, according to some reports, to accommodate 300,000 people, today it resembles a cross between a big ditch and a modern athletic field. If you know where to look you can find the start and finish lines.

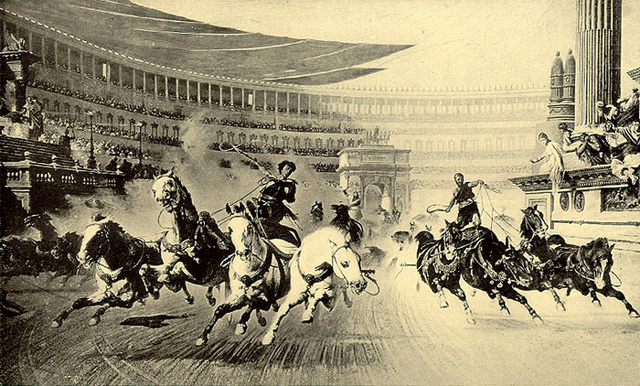

By some estimates 200,000 people showed up to watch chariot races at the Circus Maximus in Rome. A bunch of overturned chariots with maimed bodied and injured horses was called a shipwreck. The games of the circus were the oldest of the free exhibitions at Rome and always the most popular. The word circus means simply a “ring”; the ludi circenses were, therefore, any shows that might be given in a ring.” The circus is associated mostly closely with chariot races. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

For these races the first and really the only necessary condition was a large and level piece of ground. This was furnished by the valley between the Aventine and Palatine Hills, and here in prehistoric times the first Roman race course was established. This remained the circus, the one always meant when no descriptive term was added, though, when others were built, it was called sometimes, by way of distinction, the Circus Maximus. None of the others ever approached it in size, in magnificence, or in popularity.

Layout of the Circus and Arena

All the Roman circuses known to us had the same general arrangement, which will be readily understood from the plan of the Circus of Maxentius. The long and comparatively narrow stretch of ground which formed the race course (harena; English, “arena”) is almost surrounded by the tiers of seats, running in two long parallel lines uniting in a semicircle at one end. In the middle of this semicircle is a gate, marked F in the plan, by which the victor left the circus when the race was over. It was called, therefore, the porta triumphalis. Opposite this gate at the other end of the arena was the station for the chariots (AA in the plan), called carceres, “barriers,” flanked by two towers at the corners (II), and divided into two equal sections by another gate (B), called the porta pompae, by which processions entered the circus. There are also gates (HH) between the towers and the seats. The towers and barriers were called together the oppidum. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“The arena is divided for about two-thirds its length by a fence or wall (MM), called the spina, “backbone.” Beyond the ends of this were fixed pillars (LL), called metae, marking the ends of the course. Once around the spina was a lap (spatium, curriculum), and a fixed number of laps, usually seven to a race, was called a missus. The last lap, however, had but one turn, that at the meta prima, the one nearest the porta triumphalis; the finish was a straightaway dash to the calx. This was a chalk line drawn on the arena far enough away from the second meta to keep it from being obliterated by the hoofs of the horses as they made the turn, and far enough also from the carceres to enable the driver to stop his team before dashing into them. The dotted line (DN) is the supposed location of the calx. |+|

“The arena is the level space surrounded by the seats and the barriers. The name was derived from the sand used to cover its surface to spare as much as possible the unshod feet of the horses. A glance at the plan will show that speed could not have been the important thing with the Romans that it is with us. The sand, the shortness of the stretches, and the sharp turns between them were all against great speed. The Roman found his excitement in the danger of the race. In every representation of the race course that has come down to us may be seen broken chariots, fallen horses, and drivers under wheels and hoofs. The distance was not a matter of very close measurement, but varied in the several circuses, the Circus Maximus being fully 300 feet longer than the Circus of Maxentius. All seem, however, to have had a constant number of laps, seven to the race, and this also goes to prove that the danger was the chief element in the popularity of the contests. |+|

The distance actually traversed in the Circus of Maxentius may be very closely estimated. The length of the spina is about 950 feet. If we allow fifty feet for the turn at each meta, each lap makes a distance of 2000 feet, and six laps, 12,000 feet. The seventh lap had but one turn in it, but the final stretch to the calx made it perhaps 300 feet longer than one of the others, say 2300 feet. This gives a total of 14,300 feet for the whole missus, or about 2.7 miles. Jordan calculates the missus of the Circus Maximus at 8.4 kilometers, which would be about 5.2 miles, but he seems to have taken the whole length of the arena into account, instead of considering merely that of the spina. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Parts of the Arena Related to Horse Racing

Spina divided the race course into two parts, and thus measured a minimum distance to be run. Its length was about two-thirds that of the arena, but it started only the width of the track (plus the metae) from the porta triumphalis; a much larger space at the end near the porta pompae was left entirely free. It was perfectly straight, but did not run precisely parallel to the rows of seats; at the end B in the exaggerated diagram B.C. is greater than the distance AB, in order to allow more room at the starting line (linea alba), where the chariots would be side by side, than farther along the course, where they would be strung out. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Metae, so named from their shape, were pillars erected beyond the two ends of the spina and architecturally related to it, though there was a space between the meta and the spina. In Republican times the spina and the metae must have been made of wood and movable, in order to afford free space for the shows of wild beasts and the exhibitions of cavalry that were originally given in the circus. After the amphitheater was devised, the circus came to be used primarily for races, and the spina became permanent. It was built up, of massive proportions, on foundations of concrete and was usually adorned with magnificent works of art that must have entirely concealed horses and chariots when they passed to the other side of the arena. |+|

Carceres were the stations of the chariots and teams when ready for the races to begin. They were a series of vaulted chambers entirely separated from one another by solid walls, and closed behind by doors through which the chariots entered. The front of each chamber was formed by double doors of grated bars admitting the only light which it received. From this arrangement the name carcer was derived. Each chamber was large enough to hold a chariot with its team, and, as a team was composed sometimes of as many as ten horses, the “prison” must have been nearly square. There was always a separate chamber for each chariot. Up to the time of Domitian the highest number of chariots was eight, but after his time as many as twelve sometimes entered the same race, and twelve carceres had, therefore, to be provided. They were a series of The usual number of chariots had been four, one from each syndicate, though each syndicate might enter more than one. Half of these chambers lay to the right, half to the left of the porta pompae. |+|

“It will be noticed from the plan that the carceres were arranged in a curved line. This is supposed to have been drawn in such a way that all the chariots, no matter which of the carceres one happened to occupy, would have the same distance to travel in order to reach the beginning of the course proper at the nearer end of the spina. There was no advantage in position, therefore, at the start, and places were assigned by lot. They were a series of In later times a starting line (linea alba) was drawn with chalk between the second meta and the seats to the right, but the line of carceres remained curved as of old. At the ends of the row of carceres, towers were built which seem to have been the stands for the musicians; over the porta pompae was the box of the chief state official of the games (dator ludorum) ,and between his box and the towers were seats for his friends and persons connected with the games. The dator ludorum gave the signal for the start with a white cloth (mappa). One image showed a victor pausing before the box of the dator to receive a prize before riding in triumph around the arena. |+|

Spectator Area of the Circus Maximus

For the protection of the public at the games which he celebrated in 55 B.C., Pompey erected iron barriers round the arena of the Circus Maximus where twenty elephants were pitted against armed Gaetulians. But to the terror of the spectators the iron bars buckled in many places under the impact of the terrified monsters. To avoid a similar panic in future, Caesar in 46 B.C. enlarged the arena tothe east and west and surrounded it with a moat filled with water. At the same time he built, or rebuilt, the carceres in volcanic tufa stone, and carved out the face of the hillsides so as comfortably to accommodate in tiers 150,000 spectators, seated at their ease. His adopted son was to complete the work. In consultation with Octavius, Agrippa in 33 B.C. doubled the system of signals by alternating seven bronze dolphins (delphini) with the seven eggs along the spina, and having them reversed at each fresh lap. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Later Augustus brought from Heliopolis the obelisk of Rameses II, which today graces the Piazza del Popolo, to occupy the center of the circus. And above the cavea on the Palatine side he set up for himself, his family, and his guests the "royal enclosure" (the pulvinar) which he mentions in his Res Gestae? From the beginning of the empire the pulvinar showed the Romans, overwhelmed by the sight of so much imperial majesty, a sort of first sketch of the future kathisma from which the kings would one day command the Hippodrome of Constantinople.

It seems to have been Claudius who first introduced stone seats for the senators, at the same time replacing the wooden metae by posts of gilded bronze and the tufa of the carceres by marble. More stone seats were erected by Nero, this time for the Equites, when he rebuilt the circus after the great fire of A.D. 64 and took the opportunity to enlarge the track by filling in the euripus Later Trajan completed the enlargement of the cavea by deepening the excavations into the hills, a workwhich Pliny the Younger claimed in his Panegyric had increased the number of spectators' seats by 5,000.

By this time the Circus Maximus had reached the colossal dimensions of 600 by 200 meters, and had achieved its final imposing form. Its curving exterior displayed three arcades faced with marble, superimposed like those of the Colosseum. Under these arcades wine merchants, caterers and pastry-cooks, astrologers and prostitutes had their place of business. Inside, the track was now covered with a bed of sand which sparkled with bright mineral grain. The most striking thing, however, was the cavea, whose treble tiers faced each other along the Palatine beneath the imperial pulvinar and along the Aventine. The lowest tier of seats was of marble; the second of wood; while the third seems to have offered standing places only. The Regionaries of the fourth century compute 385,000 places in all. We must perhaps allow for some exaggeration in their estimate, but it is safe to pin our faith to the 255,000 seats which we can deduce from the testimony of the elder Pliny for the Flavian period, plus the additional 5,000 attributed to Trajan by Pliny the Younger.

Even with these allowances the figure is staggering — the Circus Maximus when in use seemed a city in itself, ephemeral and monstrous, set down in the middle of the Eternal City. The most surprising thing about the giant structure was the ingenuity of the details which fitted it to perform its functions. At the two ends were two corresponding arched enclosures. That on the east, toward the Mons Caelius, was broken by the three-bayed triumphal arch which the Senate and the Roman people consecrated in 81 A.D. to the victory of Titus over the Jews, and beneath which filed the procession of the Pompa Circensis. That on the west, toward the Velabrum, contained, on the ground floor, the twelve car ceres where chariots and horses waited to begin the race as soon as the rope that was stretched between the two marble Hermes outside each of the twelve doors should fall; the story above was occupied by the. tribune reserved for the curule magistrate who was presiding over the games, and for his imposing suite.

Seating at the Circus Arena

The seats around the arena in the Circus Maximus were originally of wood, but accidents owing to decay and losses by fire had led by the time of the Empire to reconstruction in marble, except perhaps in the very highest rows. The seats in the later circuses seem from the first to have been of stone. At the foot of the tiers of seats was a marble platform (podium) which ran along both sides and the curved end; it was therefore coextensive with them. On this podium were erected boxes for the use of the more important magistrates and officials of Rome, and here Augustus placed the seats of the senators and others of high rank. He also assigned seats throughout the whole cavea to various classes and organizations, separating the women from the men, though up to his time they had sat together. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Between the podium and the track was a metal screen of openwork. When Caesar showed wild beasts in the circus, he had a canal ten feet wide and ten feet deep dug next the podium and filled with water as an additional protection. Access to the seats was provided from the rear; numerous broad stairways ran up to the praecinctiones, of which there were probably three in the Circus Maximus. The horizontal sections between the praecinctiones were called maeniana. Each of these sections was divided by stairways into several cunei; the rows of seats in the cunei were called gradus. The sittings in the row do not seem to have been marked off any more than they are now in the bleachers at our baseball grounds. When sittings were reserved for a number of persons, they were described as so many feet in such a row (gradus) of such a wedge (cuneus) of such a section (maenianum). |+|

“The number of sittings testifies to the popularity of the races. The little circus at Bovillae had seats for at least 8000 people, according to Huelsen, that of Maxentius for about 23,000, while the Circus Maximus, accommodating 60,000 in the time of Augustus, was enlarged to a capacity of nearly 200,000 in the time of Constantius. The seats themselves were supported upon arches of massive masonry; an idea of their appearance from the outside may be had from the exterior view of the Coliseum. Every third vaulted chamber under the seats seems to have been used for a staircase; the others were used for shops and booths, and in the upper parts, as rooms for the employees of the circus, who must have been very numerous. Galleries seem to have crowned the seats, as in the theaters, and balconies for the emperors were built in conspicuous places, but we are not able, from the ruins, to fix precisely their positions. A general idea of the appearance of the seats from within the arena may, however, be had from an attempted reconstruction of the Circus Maximus, although the details are uncertain. |+|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024