Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

ANIMALS IN ANCIENT ROME

In antiquity cheetah and ostriches were found as far north as the Black Sea. Lions, tigers, wild cats and great herds of wild cattle roamed Dacia in the first century B.C. Pliny mentioned unicorns in his natural history encyclopedia.

In antiquity cheetah and ostriches were found as far north as the Black Sea. Lions, tigers, wild cats and great herds of wild cattle roamed Dacia in the first century B.C. Pliny mentioned unicorns in his natural history encyclopedia.

Zebra, given as gift to Emperor Caracalla, were first displayed at the Roman Colosseum in A.D. 200. Giraffes and lions were first introduced at around the same time. The Roman Emperor Elagabalus ordered 600 ostriches killed so his cooks could make him ostrich-brain pies. Geese famously warmed the Romans of the Gallic invasion in 390 B.C.

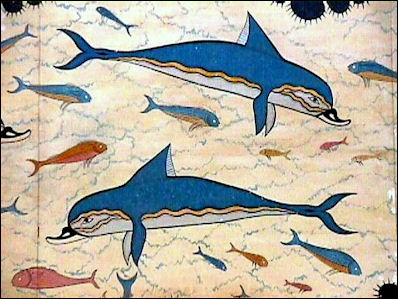

According to the ancient Greeks dolphins were originally pirates that mistakenly kidnapped Dionysus, the god of wine. To punish the kidnappers for their deed the god of wine turned their ship sails into grape vines, and when the pirates leaped into the water the turned into dolphins.┵

Pliny the Elder wrote about a dolphin that fell in love with a boy. The boy used to call for the dolphin on his way to school in Pozzouli near Naples and feed his friend fish from his hand. The dolphin used to let the boy ride on his back across the bay. One day the boy died and after coming day after day to the meeting place on the bay and not finding the boy there the dolphin passed away" undoubtably from longing. [Source: Robert Leslie Conly, National Geographic, September 1966]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Lions, of course, were not indigenous to Europe and were exported to Rome from Mesopotamia and Africa at considerable expense. For both the Romans and, later, the English they had a particular status as “king of the beasts.” A top-quality lion cost as much as 600,000 sesterces while a second-class lioness fetched 400,000 (Compare this to the mere 1000 sesterces going rate for a bear). Roman emperors found other uses for them as well. The emperors Caracalla and Elagabalus kept lions; the latter’s pets were de-fanged and de-clawed and Elagabalus enjoyed unleashing these modified predators upon his dinner guests as a heart-attack inducing prank. They had other uses, too. According to Aelian, Queen Berenice kept a pet lion who acted as a part time aesthetician; he would lick her face with his tongue and “smooth away her wrinkles” (Aelian Nat. an. 5.39). Given the expense and manifold uses for lions, actually killing one in the arena for entertainment was a way of saying that you had money to burn. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, August 29, 2021]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome” by George Jennison (1937) Amazon.com;

“Roma Canes Mundi” (“The Dogs of Ancient Rome”) (English Edition) by Giovanni Padrone (2022) Amazon.com;

“Birds in Roman Life and Myth” by Ashleigh Green (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Culture of Animals in Antiquity” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and Sian Lewis (2020) Amazon.com;

“Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman Antiquity” by Thorsten Fögen and Edmund V. Thomas (2017) Amazon.com;

” Origins In Search of Ancient Dog Breeds: First Volume - From Prehistory to Ancient Greece” by Padrone Giovanni (2021) Amazon.com;

“Women and Weasels: Mythologies of Birth in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Maurizio Bettini and Emlyn Eisenach (2024) Amazon.com;

“On Horsemanship” by Xenophon Amazon.com;

“Leisure and Ancient Rome” by J. P. Toner (1998) Amazon.com;

“Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome” by J.P.V.D. Balsdon (1969) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Pets in Ancient Rome

Cats, rabbits and peacocks were introduced to Rome by the A.D. 1st century. White tortoises were popular pets. Some Romans used to keep honking geese rather than watchdogs to alert them of intruders. Some emperors kept lions outside their bed chambers.

Pompeii mosaic of a bird feeder

Pets were even more common then than now, and then as now the dog was easily first in the affections of children. The house cat began to be known at Rome in the first century A.D. Birds were very commonly made pets. Thus besides the doves and pigeons which are familiar to us, ducks, crows, and quail, we are told, were pets of children. So also were geese, odd as this seems to us, and there is a statue of a child struggling with a goose as large as himself. Monkeys were known, but could not have been common. Mice have been mentioned already. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Jana Louise Smit wrote for Listverse: “When it comes to ancient Rome’s animal policies, one can be forgiven if the first image that comes to mind is gory slaughter at the Colosseum. However, private citizens cherished their household pets. Dogs were by far the favorite, but cats were not uncommon. House-snakes were appreciated as ratters, and domesticated birds were also delighted in. Nightingales and green Indian parrots were all the rage because they could mimic human words. [Source: Jana Louise Smit, Listverse, August 5, 2016 ]

“Cranes, herons, swans, quail, geese, and ducks were also kept. While the last three proved very popular, Roman fondness and treatment of peacocks was almost on par with dogs. Some cruelty existed in bird fighting, but it wasn’t a widespread sport. Roman pets were so deeply loved that they were immortalized in art and poetry and even buried with their masters. Other pets included hares (a popular gift exchanged by lovers), goats, deer, apes, and fish.”

Ancient Romans gave their beloved pets individual burials. One well-known tombstone reads: “I am in tears, while carrying you to your last resting place as much as I rejoiced when bringing you home in my own hands fifteen years ago.”) Archaeologists have found remains of farm animals such chickens, cows, pigs, and cattle in Britain that they believe were “used in ritual or ceremonial activities rather than for food.

Roman-Era Pigeon Towers Discovered in Luxor, Egypt

In January 2023, archaeologists with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said they found a number of Roman-era pigeon towers (where pigeons could be raised for eating) in a residential area of Luxor. A variety of artifacts were also uncovered, including pottery, bells, grinding tools (often used for food preparation), and Roman coins made of copper and bronze. [Source Owen Jarus, Live Science, January 27, 2023]

Live Science reported: The residential area is close to Luxor Temple, a large religious center built during the reigns of several pharaohs before the Roman Empire, including Amenhotep III, Ramesses II and Tutankhamun. But the residential area dates to much later, during the second and third centuries A.D. During this time, Egypt was a Roman province and Roman emperors were sometimes depicted as pharaohs.

The team found that when the Romans took over Luxor, they started raising pigeons by erecting pigeon towers containing pots that the pigeons could use as nests, the statement said. Pigeons are the descendants of rock doves (Columba livia), which breed on rocky, coastal cliffs; but towers can mimic cliff conditions, making the birds feel right at home.

Pigeons have a long history. They were domesticated by the Egyptians and Romans. Nero used them to send messages about the results of Imperial games to his friends. Many were kept as sources of meat that were available throughout the year. Their ancestors, rock pigeon, lived on cliffs and in caves on the coast. Domesticated pigeons were provided with tall towers with ledges for them to roost that simulated their coastal homes.

Sacred Geese Save Romans From Complete Annihilation

The Gauls were unable to take the center of Rome, at Campidoglio, the legend goes, because, a group of honking geese alerted the Roman of the nighttime attack. According to National Geographic: Sacred geese lived in the goddess Juno’s temple on Capitoline Hill during the Roman Republic. This gaggle became a band of unlikely heroes when the Gauls sacked the city in 387 B.C. It was the geese that prevented the last stronghold in Rome from falling into the hands of the Gauls. [Source Javier Negrete, National Geographic History, February 15, 2024]

The story appears in Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, written around the second century A.D.: “There were some sacred geese near the temple of Juno, which were usually fed without stint, but at that time, since provisions barely sufficed for the garrison alone, they were neglected and in evil plight. The creature is naturally sharp of hearing and afraid of every noise, and these, being specially wakeful and restless by reason of their hunger, perceived the approach of the Gauls, dashed at them with loud cries, and so waked all the garrison.

Dogs in Ancient Rome

Dogs in ancient Greece often were not fed. They were expected to catch their meals. The Romans fed their dogs and appear to have pampered them. The remains of a dog buried with a collar made of semiprecious stones have been found.

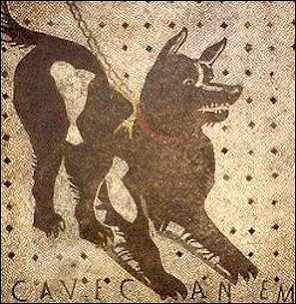

At Pompeii, archaeologists found remains of a chained dog and mosaic with a snarling dog and a sign that said "Cave Canem" (“Beware of the Dog”). Petronius wrote in Satyricon: “There on the left as one entered…was a huge dog with a chain round its neck. It was painted on the wall and over it, in big capitals, was written: Beware of the Dog.” A graffiti inscriptions from Pompeii reads: “On October 17 Puteolana had a litter of three males and two females.”

Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine, “One of the most charming signs of dog life at Roman villas, farms, and military camps across Britain are the pawprints left in drying building tiles. There are dozens of these tiles from Silchester, and hundreds from Roman Britain — perhaps as many as one percent of all the tiles produced there according to Fulford — proof that it is not just modern dogs who stick their paws where they may not belong."

Attitudes Towards Dogs in Ancient Rome

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: For the Romans, dogs fell into one of two camps: domesticated helpers and scavenger outsiders. In his Georgics the poet Virgil advises the estate owner to choose their companions based on one of two qualities: their ability to defend the estate and its four-footed residents from wild animals, and their ability to assist in hunting. There are, in other words, hunting dogs and sheep dogs, just as there are cultivated lands and uncivilized countryside and woods. The poet Grattius identified the Umbrian dog, for his loyalty and sense of smell, but notes that you wouldn’t want him in a fight. And as a group dogs have a kind of liminal status: they can be barbaric wild beasts with predatory urges or domesticated faithful insiders. They capture the uncertainty we encounter in other people: they might be friends or enemies.[Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 16, 2022]

Dogs were known for presenting their owners with other challenges. If they got too hungry, they might attack you or your flock. The agricultural writer Columella appears to know about rabies or canine madness, which he puts down to feeding your dogs a mixture of bread and beans. Nevertheless, in both cities and countryside villas the home was guarded by chained watchdogs, who were positioned in the atrium. Excavations at the House of Vesonius in Pompeii revealed one unfortunate animal still chained to a doorpost. Dogs could serve a religious purpose too: Cerberus the three-headed hell-hound prevented the dead from leaving the underworld.

There were some, of course, who loved dogs. After all, they are adorable. The Epicurean philosopher Lucretius appears to have been a fan and provides a vivid account of dogs twitching their bodies as they dreamt of hunting in their sleep. But at the same time, in antiquity necrophagia, or corpse eating, was associated with dogs as they were known for feasting on unburied corpses.

Dog Crucifixion and Healing in Ancient Rome

Beware of dog sign from Pompeii

A copper alloy Roman dog statue, dated to A.D. 318–450 and measuring 21 x 12.5 x two centimeters (8.4 x 5.2 x 1.9 inches), was found in Gloucestershire, England. According to Archaeology magazine: “This finely crafted canine may have a connection to ancient medicine. The statue was found recently in a hoard of more than 30 artifacts, all of which — with the exception of the dog — were deliberately broken, says archaeologist Kurt Adams of the Portable Antiquities Scheme. The dog is depicted with its tongue protruding — either panting, or, says Adams, perhaps more likely, licking. It’s possible that the statue was associated with a cult center not far from where the hoard was found. “Representations of licking dogs are very rare and they are often associated with healing,” says Adams. “It’s tempting to draw connections with the nearby Roman temple at Lydney, which was dedicated to Nodens, a god of hunting, the sea, and, importantly for us, healing.” [Source: Archaeology magazine, January-February 2018]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: If dogs failed in their duties, however, they could find themselves in hot water. In one famous story relayed by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, they failed to prevent an attack by the Gauls in 390 B.C. The putative invaders managed to escape the notice of guards and watchdogs but were spotted by the beady-eyed sacred geese of Juno. The geese roused the inhabitants and the city was saved. In tribute to this, dogs were crucified once a year near the Circus Maximus as a reminder and punishment for the betrayal. Geese, meanwhile, were carried on litters adorned with cushions of imperial purple and gold. Like other animals, dogs were regularly caught up in the sacrificial mechanics of ancient religious practice: they may have found themselves on the proverbial chopping block at celebrations of Lupercalia (the sexually charged celebration of the survival of Romulus and Remus on Feb. 15); at Robigalia (a festival to placate a difficult goddess who might spoil the harvest); as offerings to the underworld deity Genita Mana; and during agricultural festivals. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 16, 2022]

“In Italy,” Dr. Mark Letteney, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT, told the Daily Beast, “we have good evidence for, and studies of, dog sacrifice, and particularly puppies” by scholars like Victoria Moses, Jacopo De Grossi Mazzorin, Claudia Minniti, and Barbara Wilkens. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 29, 2023]

Dogs of Roman Britain

Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine, “Evidence for dogs in Roman Britain is plentiful. Decades of excavations have uncovered dozens of dogs of all types, ranging from terrier- to Labrador- and even greyhound-sized. Some were stillborn or died at birth, while others lived to ripe old ages. And although a few dogs show clear signs of having been killed deliberately, at least one was very well treated. Although the dog was rendered permanently lame by multiple leg fractures, it bore no trace of infection, suggesting that its paw was cleaned and immobilized, allowing it to heal properly. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell,Archaeology magazine, September/October 2010]

"There were quite a lot of dogs here, and in Roman Britain in general," says Michael Fulford, director of the excavations at Silchester, the site of the large Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum in southern England. "What's interesting too is that dogs were treated both as rubbish and also reverentially," says Fulford. His team found an early third-century A.D. pit with the remains of a puppy that was killed (the team is not sure how), two other dogs, a raven, and two doubly-pierced pot sherds. The dogs were also buried with a knife that was probably used as a razor and had an ivory handle in the form of two coupling dogs. According to Nina Crummy, the excavation's finds specialist, the burial of the knife, an expensive object that had been made on the continent, would not have been lightly undertaken. "It should be interpreted as a deliberate burial, either as a kind of grave gift accompanying the burial of a pair of valued dogs, or a votive offering connected with the ritual life of the inhabitants [of this area of the city]," she says.

The dogs from Silchester are also evidence that in the Roman world, small dogs were favored over larger ones. According to University of Winnipeg archaeologist Michael MacKinnon, the spread of toy breeds by the Romans represents shifting attitudes toward pet-keeping, or an ardent effort to incorporate pet ownership into the more regular uses of dogs, such as herding and guarding. "It seems to be a Roman phenomenon that I suspect ties in with conspicuous consumption by the elite and other attempts at wealth and showiness," says MacKinnon. Archaeological evidence from the Roman world, including Silchester, also suggests that they may have been breeding for smaller dogs. "Bow-legged animals occur [starting in the] early Romano-British period, as does the absence of the lower third molar and crowding of the premolars," says Kate Clark, the Silchester team's bone specialist. "These conditions are due to the rapid diminution of the species whereby jaw size decreases faster than tooth size."

Dog Breeds in Ancient Rome

Bloodhounds are thought to date back at least to Roman times. In the A.D. 3rd century, the historian Claudius Aelianus described a breed of dog with a superior scenting ability and was so determined that it would not leave the trail until its quarry was found.

The Romans also bred large, powerful dogs for battle. They were capable of knocking an armed man off a horse and dismembering him. Mastiffs — or at least those more properly described as Old English Mastiffs — were originally bred as fighting dogs for the Roman legions. There is some evidence these originally came from Britain. Caesar described them in his account of invading Britain in 55 B.C. When these dogs fought beside their masters against the Roman legions, he wrote, they displayed such courage and power it left a great impression. Not long afterwards there were accounts of huge British fighting dogs defeating all comers in battles in the Circus. They were matched against human gladiators as well as bulls, bears lions and tigers.

French-Bulldog-Like Dog Found in Roman-Era Tomb in Turkey

Pompeii dog Flat-faced dogs like pugs and bulldogs and technically known as brachycephalic dogs. The remains of one was found in a 2,000-year-old tomb in Turkey, offering evidence that the ancient Romans likely bred flat-faced dogs as companions. Buried alongside its likely owner, the remains of the small dog has features that resemble a French bulldog, and are among the oldest-known examples of a brachycephalic dog ever discovered. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, National Geographic, August 14, 2023]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in National Geographic, The discovery, published in 2023 in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, was made in 2007 at the ancient necropolis of Tralleis located just outside the modern city of Aydın on Turkey’s Aegean coast. Among the Roman and Byzantine-era tombs was one containing the remains of an adult human and the dog, with the dog likely killed to be buried with its owner, in what may have been a tradition at the time; it was also placed carefully on its side with its head facing east, like the human it was laid to rest with.

An analysis of the Tralleis dog’s remaining skull and jaw was done in 2021 by a team led by zooarchaeologist Vedat Onar of Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa. Based on skull proportions that show an acute degree of brachycephaly, the researchers determined that the ancient canine was the size of a modern Pekingese and resembled a modern French bulldog. This is only the second find of a Roman-era dog skull that has these flat-faced features — the other was discovered in Pompeii in the 18th century, and dates from the destruction of the city by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Although flat-faced dogs aren’t specifically mentioned in Roman writings or depicted in their art, this second find suggests that the Romans were selectively breeding such features for pet dogs, Onar says. He acknowledges the remote chance that the surviving examples may just reflect random genetic mutations limited to only those two brachycephalic dogs; nonetheless, their small size supports the idea that the dogs were bred as pets: “This dog skull found in Tralleis can be seen as a phenomenon of artificial selection, which was achieved by reinforcing desired traits,” the study notes.

Most Roman-era dogs were working animals for hunting, guarding, and herding, and injuries to their bones reveal they were often not treated well. The Tralleis dog, however, has no such injuries, while an analysis of its teeth suggest it ate little hard food. These discoveries, along with estimates of the dog’s tiny size, suggest to Onar and his colleagues that it was a cherished pet: a catella, or “lapdog” rather than a hunting dog (canis venaticus) or guard dog (canis villaticus). “Maybe [the Tralleis dog] was the best friend and companion of the deceased, who probably included in his last will the wish of a common burial,” the study authors speculate.

Dachshund-Like, Roman-Era Dog Found in Britain

In 2023, archaeologists in England found remains of a lap dog from over 1,800 years ago in a villa, according to Smithsonian. Vishnu Warrier wrote in Dog Time: The discovery suggests the British kept small-sized dogs as pets at that time The animal whose remains were discovered was 20 centimeters (7.8 inches tall). The canine, which was the size of a Chihuahua, is one of the shortest Roman-era dogs discovered in the United Kingdom. [Source: Vishnu Warrier, Dog Time, January 25, 2024]

DigVentures, an excavation company in the U.K., found the remains near the Wittenham Clumps in Berkshire, known as The Clumps. According to their team, the canine was believed to be female and resembled a Dachshund. Archaeologists Hannah Russ and Sarah Everett said the dog’s small size and her “bowed legs” suggest she was not bred for hunting. “This, along with the fact that she might have even been buried with her owner, makes it far more likely that she was kept as a house dog, lap dog or pet.” “In the UK, most of the small dogs we find measure between 22–37 centimeters in shoulder height, making this individual particularly small,” they added. Additionally, there were “at least 15 small-medium sized” dogs whose remains were buried at the site. As per Russ and Everett, the other larger dogs were believed to have been used for hunting and game purposes.

Adam Vaughan of The Times said lap dogs weren’t found on the island during the pre-Roman Britain era. “You find medium and large-sized working ones, probably for hunting and guarding,” he noted. During this period, these dogs were also used for herding, killed for fur, or sometimes even sacrificed. However, post the Roman invasion, several other breeds were brought to the island. Most of them looked similar to the larger pups but were much smaller in size. Some of them had chondrodysplasia, a genetic condition causing dwarfism. They were later crossbred to produce canines with bowed legs, giving the appearance of a Dachshund.

These discoveries paint a fascinating portrait of the Roman Empire. “When we think about the Romans, we’re always given stories of the military and how brutal they were,” Pina Dacier told The Telegraph. “But here’s a villa where you can see a family was living and what their family life was like.” She continued, “They’ve got their tiny dog, which they would have loved just as we all love our pets today.”

Pompeii mosaic of cats and birds

Yasmina 'Sick' Dog

"Perhaps of all the archaeological cases for pets I can think of," Michael MacKinnon, an archaeologist from the University of Winnipeg told Archaeology magazine, "I believe the Yasmina 'sick' dog is the most poignant." Along the north wall of the Roman-era Yasmina cemetery in the city of Carthage in Tunisia, excavations led by Naomi Norman of the University of Georgia uncovered a third-century A.D. burial of an adolescent/young adult in a carefully made grave topped with cobbles and tiles, and with the skeleton of an elderly dog at its feet. The dog was also buried with one of the few grave goods found in the cemetery, a glass bowl carefully placed behind its shoulder. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell, Archaeology magazine, September/October 2010]

Jarrett A. Lobell and Eric Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine, “The Yasmina dog, which probably resembled a modern Pomeranian, is an example of a toy breed, and one of the earliest specimens to be identified as a Maltese. But what is more remarkable about the dog is that, despite a host of physical problems including tooth loss that likely required it to eat soft foods, osteoarthritis, a dislocated hip, and spinal deformation that would have limited mobility, the dog survived into its mid-to-late teens. It was clearly well cared for, and even death could not separate it from his owner, according to MacKinnon. "Whether the dog represents a sacrifice [perhaps meant to 'heal' the sick person in the afterlife] or just companionship is unknown, but these two aspects need not be mutually exclusive," he says. "There is a great connection between humans and animals in Roman antiquity. To me, this aspect of animals garnering sentimental value and being treated like humans is a key aspect of Roman culture."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024