Home | Category: Life, Homes and Clothes

BATHING IN ANCIENT ROME

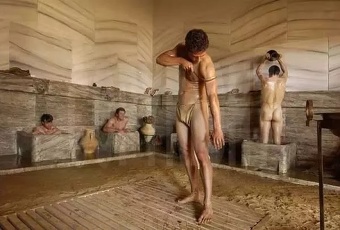

The Romans took Greek bath culture and raised it to a higher level. Their bathhouses became “masterpieces of art” in which “the customer could wander about, sampling each cold, hot, tepid or steam bath." Roman baths, known as thermae, became a prime source of entertainment and enjoyment that evolved into a way of life that endured until Christian ideology became dominate and vilified Roman-style bathing as decadent.

On the Forum Baths at Pompeii which appear to have been built soon after Pompeii became a Roman colony, Dr Joanne Berry wrote for the BBC: “ Baths were an important part of Roman life, and it was a Roman custom to visit the baths daily, both for reasons of cleanliness and to conduct business or meet friends. [Source: Dr Joanne Berry, Pompeii Images, BBC, March 29, 2011]

The bath was regularly taken between the meridiatio (midday siesta) and the cena (dinner) ; the hour varied, therefore, within narrow limits in different seasons and for different classes. In general it may be said to have been taken about the eighth hour, and at this hour all the conductores were bound by their contracts to have the baths open and all things in readiness. As a matter of fact many persons preferred to bathe before the prandium, and some, at least, of the baths in the larger places must have been open then. All were regularly kept open until sunset, but in the smaller towns, where public baths were fewer, it is probable that they were kept open later; at least the lamps found in large numbers in the Pompeian baths seem to point to evening hours. It may be taken for granted that the managers would keep the doors open as long as was profitable. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

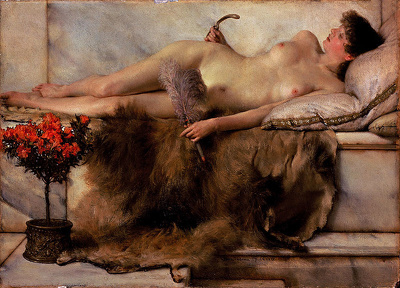

The emperor Commodus (A.D. 161-192) took eight bathes a day and saw himself as a sort reincarnation of Hercules. Nero's wife is said to have bathed in donkey milk scented with rose oil. Cleopatra preferred to bathe in freshly-squeezed goat milk."

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATHS IN ANCIENT ROME: HISTORY, TYPES, PARTS factsanddetails.com ;

BEAUTY AND COSMETICS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

HYGIENE AND BODY FUNCTIONS IN ANCIENT ROME: CLEANLINESS, PERFUME, FARTS AND PEE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

TOILETS IN ANCIENT ROME: DISGUSTING PUBLIC ONES, CHAMBER POTS AND TAXES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Bathing in the Roman World” by Fikret Yegül Amazon.com;

“Bathing in Public in the Roman World” by Garret Fagan.(1999) Amazon.com;

“A Cultural History of Bathing in Late Antiquity and Early Byzantium”

Amazon.com;

“Pollution and Religion in Ancient Rome” by Jack J. Lennon (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Essential Roman Baths” by Stephen Bird (2007) Amazon.com;

"Roman Bath” by Peter Davebport (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Roman Bath” by Patricia Southern (2013) Amazon.com;

“Roman Baths” by Barry Cunliffe (1980) Amazon.com;

“Baths of Caracalla: Guide” by Gail Swirling (2008) Amazon.com;

“Decoration and Display in Rome's Imperial Thermae: Messages of Power and their Popular Reception at the Baths of Caracalla” by Maryl B. Gensheimer (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Baths of Caracalla” by Piranomonte Marina Amazon.com;

“The Baths of Caracalla: A Study in the Design, Construction, and Economics of Large-Scale Building Projects in Imperial Rome” by Janet Delaine (1997)

Amazon.com;

“Cosmetics & Perfumes in the Roman World” by Susan Stewart (2007) Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume I: Books 1–4" (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Hygiene, Volume II: Books 5–6. Thrasybulus. On Exercise with a Small Ball (Loeb Classical Library) by Galen and Ian Johnston Amazon.com;

“Pearls and Petals Beauty Rituals in Ancient Greece and Rome” by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy: Toilets, Sewers, and Water Systems”

by Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow (2018) Amazon.com;

“Public Toilets (Foricae) and Sanitation in the Ancient Roman World: Case Studies in Greece and North Africa” by Antonella Patricia Merletto (2023) Amazon.com;

“Latrinae et Foricae: Toilets in the Roman World”, Illustrated, by Barry Hobson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities”

by Alberto Angela, Gregory Conti (2009) Amazon.com

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Roman Bathing Lifestyle

People did not bath in their homes in the evening or morning. Most houses didn't have baths. Most people bathed in the afternoon in public baths. By the time of Jesus, almost every village and town had at least one public bath. Some of them were donated by rich citizens; other charged admission, with the admission price being low enough in most cases that everyone was welcome. A census during the first century A.D. counted more than 1000 such facilities in Rome (a fivefold increase from a 100 years before). Baths were so popular that government passed laws regulating opening and closing times. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Bathing was such a big part of Roman life that much has been written about them. But from what we can ascertain they were more like resort beaches than Turkish bathes. Vendors sold food and drink. People were even warned about eating before they went bathing. "You will soon pay for it my friend," Juvenal warned a friend, "if you take off your clothes and with distended stomach and carry your peacock into the bath undigested!"

The early inhabitants of Rome might bathe their arms and legs daily, but they only took a full bath about once a week. As Romans became more wealthy and the desire for luxury grew, more and more Romans began to attend public baths. According to Encyclopedia.com: Public baths were civic gathering places, perhaps like a modern gym or health club, dedicated to bathing and exercise. In the larger towns these public baths were very elaborate. They had sauna rooms and heated and chilled pools. Romans developed complex rituals about their baths; they might move through four baths of different temperatures before exercising. Men and women bathed separately: women typically bathed every morning, while men bathed in the late afternoon. All citizens in a town could attend the public baths for a small fee, but the wealthiest Roman citizens had richly decorated private baths. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Temples sometimes had their own baths. Excavations near a temple in Esna, Egypt, uncovered a multi-level bathroom dating to Roman times. In the bathroom, archaeologists found bathtubs, a possible bathing seat and corridors for hot air and water to reach the tubs.

Staying Clean in Ancient Rome

Roman men that could bathed daily. That was their main form of body care and adornment aside from perhaps wearing a signet ring. In Roman times, people generally didn't use soap, they cleaned themselves with olive oil and a scraping tool. A wet sponge placed on a stick was used instead of toilet paper.

Adam Hart-Davis wrote for the BBC: “Most of the business of bathing was for pleasure and recreation, rather than for keeping clean. To clean off the dirt they went through a hot room in the baths, like a sauna or a Turkish bath, and then rubbed oil on their skin, and scraped off the mucky mixture of oil, sweat, and dirt, using a curved metal scraper called a strigil. I tried this out and found it remarkably effective, although I don't quite know how they managed to clean their backs - I think I would rather have a slave do it. Apparently Roman ladies used to collect the sweaty gloop from athletes and gladiators and use it in a face pack - but no one offered to try mine! [Source: Adam Hart-Davis, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Nero bathed in rose oil wine. He once spent 4 million sesterces (the equivalent of $200,000 in today's money) on rose oils, rose water, and rose petals for himself and his guests for a single evening. At parties he installed silver pipes under each plate to release the scent of roses in the direction of guests and installed a ceiling that opened up and showered guests with flower petals and perfume. According to some sources, more perfumes was splashed around than were produced in Arabia in a year at his funeral in A.D. 65. Even the processionary mules were scented.

History of Bathing in Ancient Rome

To the Roman of early times the bath had stood for health and decency only. He washed his arms and legs every day, for the ordinary costume left them exposed; he washed his body once a week. He bathed at home, using a primitive sort of wash-room; it was situated near the kitchen in order that the water heated on the kitchen stove might be carried into it with the least inconvenience. By the last century of the Republic all this had changed, though the steps in the change cannot now be followed.” [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

In the A.D. 4th century, Rome had 11 massive and luxurious public bathhouses, more than 1,350 public fountains and cisterns and hundred of private baths. Served by 13 aqueducts, the average Roman used 300 gallons of water a day (nearly the same as what an American family of four uses today).

Christian doctrine insisted that what was important was the cleanliness of the inner soul, with too much attention to the outer body being a sin. The early Christian church so closely associated the Roman baths with decadence and debauchery, it discouraged cleanliness. "To those that are well, and especially to the young," St. Benedict wrote, "bathing shall seldom be permitted." Saint Francis of Assisi later equated a smelly, unwashed body with piety and faith."

Socializing in Roman Baths

The Romans loved their bathes and much of Roman social life centered around them. Bathing was both a social duty and a way to relax. During the early days of Roman baths there were no rules about nudity or the mixing of the sexes, or for that matter rules about what people did when they were nude and mixing. For women who had problems with this arrangement there were special baths for women only. But eventually the outcry against promiscuous behavior in the baths forced Emperor Hadrian to separate the sexes. ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

The Romans even socialized in the restrooms. In Pompeii and the Roman colony of Lepcis Magna archeologists discovered a large bath room with seats around the edge and a pit or ditch behind the seats. The idea was that the people in the room could face one another and chat while they took care their business in the pits. "The social latrine became standard in public baths, " Boorstin wrote." If bathing could be a pleasurable social occasion, why not defecating?" ["The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin]

Women of respectability bathed in the public baths, as they bathe in public places now, but with women only, enjoying the opportunity to meet their friends as much as did the men. In the large cities there were separate baths devoted to their exclusive use. In the larger towns separate rooms were set apart for them in the baths intended generally for men. Such a combination bath is discussed in the next paragraph. It will be noted that the rooms intended for use of the women are smaller than those for the men. In the very small places the bath was opened to men and women at different hours. Late in the Empire we read of men and women bathing together, but this was true only of women who had no claim to respectability at all. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Ancient Roman Bathing Routine

Bathers first entered the tepidarium (heated by vents in the wall or floor) and sweated, relaxed and were sometimes anointed with oils and scrubbed clean by slaves (ordinary people scrubbed themselves with lentil flour). Next they entered the calidarium or laconicom for more sweating, scraping and cleaning plus some splashing under bucketsful of warm, tepid or cold water. The bath ended with a plunge into a cool pool of water in the frigidarium.

The bath which followed the games or the wrestling match was closely linked with sport. The bath itself usually consisted of three parts. First, the bather, drenched in sweat, went off to undress if he had not already done so in one of the dressingrooms or apodyteria of the baths. Then he entered one of the sudatoria which flanked the caldarium, and encouraged the sweating process in this hothouse atmosphere: this was "the dry bath." Next he proceeded to the caldarium, where the temperature was almost as warm and where he could sprinkle hot water from the large tub known as the labrum on his sweating body and scrape it with the strigil. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Cleansed and dried, he retraced his steps to the tepidarium to cool off gradually, and finally he ran to take a plunge in the cold pool of the frigidarium. These were the three phases of the hygienic bath as recommended by Pliny the Elder, as experienced by the bathers in Petronius' novel, and as suggested in the Epigrams of Martial. Martial, however, allows his imaginary interlocutors the option of cutting out one of the bathing processes: "If Lacedaemonian methods please you, you can content yourself with dry warmth and then plunge in the natural stream."

It was in practice impossible for the bather to rub himself down properly with the strigil. An assistant of some sort was indispensable, and if he had not taken the precaution of bringing some slaves of his own with him, he discovered that such assistance was by no means furnished gratis. An anecdote recorded in the Historia Augusta proves that people thought twice before they embarked on this expense.

Rules at Ancient Roman Baths

Roman baths became so popular that people had contracted the habit of attending the baths daily and spending the greater part of their leisure there. Our authorities unanimously state or imply that the thermae normally closed at sunset; but the only indications we have as to when they opened seem at first sight "to contradict each other. A line of Juvenal's suggests before noon, as early as the fifth hour; and this is confirmed by an epigram of Martial's in which the poet, choosing the most opportune moment for his bath, decides on the eighth hour which "tempers the warm baths; the hour before breathes heat too great, and the sixth is hot with excessive heat." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

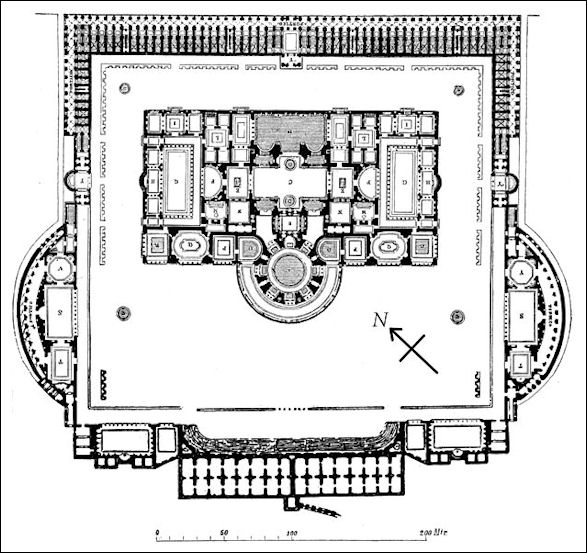

On the other hand, the Historia Augusta in the Life of Hadrian records that a decree of the emperor forbade anyone, except in case of illness, to bathe in the public baths before the eighth hour; while the Life of Severus Alexander recalls that in the preceding century bathing was not permitted before the ninth hour. Finally, several of Martial's Epigrams seem to imply that many people took their bath at the tenth hour or later, and that whatever might be the hour formally fixed for the opening of the baths and announced by the tintinnabulum of the bell, people were allowed to enter the exercise grounds before it sounded. One thing only can in my opinion help to clear up this confusion and reduce or even reconcile the discrepancies in our data: the consideration of the plan of the thermae and the administrative regulations which governed the segregation of the sexes.

Men and Women Bathing Together

In the days of Martial and Juvenal, under Domitian, and still under Trajan, there was no formal prohibition of mixed bathing. Women who objected to this promiscuity could avoid the thermae and bathe in balneae provided for their exclusive use. But many women were attracted by the sports which preceded the bath in the thermae, and rather than renounce this pleasure preferred to compromise their reputation and bathe at the same time as the men. As the thermae grew in popularity, this custom produced an outcropping of scandals which could not leave the authorities undisturbed. To put an end to them, sometime between the years 117 and 138 Hadrian passed the decree mentioned in the Historia Augusta which separated the sexes in the baths: "lavacra pro sexibus separavit." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

But since the plan of the thermae included only one frigidarium, one tepidarium, and one caldarium, it is clear that this separation could not be achieved in space, but only in time, by assigning different hours for the men's and women's baths. This was the solution enforced, at a great distance from Rome, it is true, but also under the reign of Hadrian, by the regulations of the procurators of the imperial mines at Vipasca in Lusitania. The instructions issued to the conductor or lessee of the balnea in this mining district included the duty of heating the furnaces for the women's baths from the beginning of the first to the end of the seventh hour, and for the men's from the beginning of the eighth hour of day to the end of the second hour of night. The dimensions of the Roman thermae made impossible the lighting which an exactly similar division of times would have required. But there is in my opinion not the slightest doubt that Rome adopted the same principle, modifying the detail to suit the conditions imposed by the size of her thermae. We need only take account of the plan of the Roman thermae, with the baths proper in the center and the huge annexes surrounding them, and co-ordinate this with the scattered indications found in the writers of the time, to be able to reconstruct a likely picture of the procedure.

From the statements of Juvenal we know that the doors of the annexes were opened to the public, irrespective of sex, from the fifth hour of the morning. At the sixth hour the central building was opened, but to women only after Hadrian's decree. At the eighth or ninth hour, according to whether it was winter or summer, the bell sounded again. It was now the men's turn to have access to the baths, where they were allowed to stay till the eleventh or twelfth hour. From this division of the time, it is permissible to assume that women and men undressed successively inside the central baths, and that the palaestrae within their confines were the only places where nude athletics were permitted. This conclusion need not surprise us; and it tallies with the deductions we draw from texts describing the games in which the Romans indulged in their thermae.

Games and Entertainment at Ancient Roman Baths

Gaming counters, made of bone and other materials, have been found at Roman baths. According to The Telegraph: The Romans are known to have enjoyed playing board games, and similar finds from elsewhere suggest that playing games was a common activity at bathhouses. [Source: Dalya Alberge, The Telegraph, September 10, 2023]

In the 1st-century AD Roman work of fiction Satyricon by Petronius, we main character Trimalchio meets with his friends before a grand banquet at bath time in the thermae where many people have gathered. Suddenly they spy "a bald old man in a reddish shirt playing at ball with some long-haired boys.... The old gentleman, who was in his house shoes, was busily engaged with a green ball. He never picked it up if it touched the ground. A slave stood by with a bagful and supplied them to the players." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

This was a ball game for three, called a trigon, in which the players, each posted at the corner of a triangle, flung the balls to and fro without warning, catching with one hand and throwing with the other. The Romans had many other kinds of ball games, including "tennis" played with the palm of the hand for a racquet (as in the Basque game of pelote) ; harpastum, in which the players had to seize the ball, or harpastum, in the middle of the opponents, despite the shoving, bursts of speed, and feints a game which was very exhausting and raised clouds of dust; and many others such as "hop-ball," "ball against the wall," etc. The harpastum was stuffed with sand, the paganica with feathers; the folks was blown full of air and the players fought for it as in basket ball, but with more elegance. Sometimes the ball was enormous and filled with earth or flour, and the players pommelled it with their fists like a punching bag, in much the same way that they sometimes lunged with their rapiers against a fencing post. These were some of the games which formed a prelude to the bath. Martial alludes to them in an epigram addressed to a philosopher friend who professed to disdain them: "No hand-ball, no bladder-ball, no feather-stuffed ball makes you ready for the warm bath, nor the blunted stroke upon the unarmed stump; nor do you stretch forth squared arms besmeared with sticky ointment, nor, darting to and fro, snatch the dusty scrimmage-ball."

This enumeration is far from complete and we must add simple running, or rolling a metal hoop (trochus), Steering the capricious hoop with a little hooked stick which they called a "key" was a favorite sport of women; and so was swinging what Martial called "the silly dumb-bell" (haltera), though they tired at this more quickly than the men. When playing these games both men and women wore either a tunic like Trimalchio's, or tights like those of the manly Philaenis when she played with the harpastum or a plain warm cloak of sports cut like the endromis which Martial sent to one of his friends with the gracious message : "We send you as a gift the shaggy nursling of a weaver on the Seine, a barbarian garb that has a Spartan name, a thing uncouth but not to be despised in cold December,.. whether you catch the warming hand-ball, or snatch the scrimmage-ball amid the dust, or bandy to and fro the featherweight of the flaccid bladder-ball."

For the wrestling match, on the other hand, the wrestlers had to strip completely, smear themselves with ceroma (an unguent of oil and wax which made the skin more supple), and cover this with a layer of dust to prevent their slipping from the opponent's hands. Wrestling took place in the palaestrae of the central building near some rooms which in the baths of Caracalla archaeologists have identified with the oleoteria and the conisteria. Here not only wrestler but wrestleress whose perverse complaisance under the masseur's attentions roused the wrath of Juvenal came to submit to the prescribed anointings and massage.

Roman Baths — Palaces of the People?

It has been argued that imperial Roman baths brought immense benefit to the people. In their dazzling marble grandeur the thermae were not only the splendid "Palace of Roman Water," but above all the palace of the Roman people. In them the Romans learned to admire physical cleanliness, useful sports, and culture; and thus for many generations they kept decadence at bay by returning to the ancient ideal 'which had inspired their past greatness and which Juvenal still held before them as a boon to pray for: "a healthy mind in a healthy body (orandum est ut sit mens sana in cor pore sano)". [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Hadrian^s biographer relates that the emperor often bathed in the public baths with everyone else. One day he saw there an old soldier whom he had known in the army, busily rubbing himself against the marble with which the brick walls of the caldarium were faced, and asked why he was doing this. The old man replied that you had to have money to keep slaves, whereupon the princeps provided him with both slaves and money. Not unnaturally, the next day when the emperor's presence was announced a number of old men set to rubbing against the marble. Hadrian merely advised them to rub each other down.

We are safe in assuming that only the poor took the emperor's advice. Rich people could afford to have themselves served, rubbed, massaged, and perfumed as they would. When Trimalchio's future guests left the frigidarium, they found their accidental host inundated, with perfumes and being rubbed down not with an ordinary cloth but with napkins of the finest wool, by three masseurs who, after quarrelling for the honor of grooming him, "rolled him up in a scarlet woollen coat and put him in his litter." Trimalchio, duly dried by these specialists, was hoisted on the shoulders of his retainers and carried straight home where his dinner was awaiting him.

The majority of the bathers, however, especially those whose houstf was less luxurious and whose table was less well set than Trimalchio's, lingered in the thermae and enjoyed their amenities until closing time. Groups of friends gathered in the public halls and nymphaea for conversation, or perhaps went to read in the libraries. The sites of the two libraries of the baths of Caracalla have been rediscovered at the two extremities of the line of cisterns. They are at once recognisable from the rectangular niches hollowed in the walls for the plutei, or wooden chests, which contained the precious volumina. Others walked quietly to and fro in the ambulatories of the xystus among the masterpieces of sculpture with which the emperors had systematically peopled the thermae. We must not forget that modern excavation has rescued from the baths of Caracalla the Farnese Bull, Flora, and Hercules; the Belvedere Torso, and the two basins into which Roman fountains play in the square of the Palazzo Farnese. All of these stood of old on the mosaic pavements beneath the coffered vaults, between the marble-covered walls and the colonnades with capitals decorated with heroic figures which graced.the baths. The thermae of Trajan were not less richly endowed, and from them was retrieved, among other treasures, the famous group of the Laocoon, now in the Vatican. It is impossible not to believe that the Romans, in the physical well-being and pleasant lassitude induced by exercise and bath, felt the beauty which surrounded them sink quietly into their souls.

It is true that the Romans themselves found evil to say about their thermae, and that many abuses flourished there. It is all too well established that there lurked under the stately porticoes vendors of food and drink and procurers of both sexes; that many congregated there to overeat and drink and indulge other disreputable tastes; that many heated themselves merely in order "to raise a thirst," and found bathing a stimulant for other excesses: "You will soon pay for it, my friend,' if you take off your clothes, and with distended stomach carry your peacock into the bath undigested! This leads to death and an intestate old age!" Such overindulgence in bathing as Commodus practiced who took up to eight baths a day, could only soften the muscles and exasperate the nerves. We may fairly condemn abuses which the victims cynically acknowledged: "baths, wine, and women corrupt our bodies but these things make life itself (balnea, vina, Venus corrumpunt corpora nostra sed vitam faciunt)."

Items Lost in Drains Offer Insights Into Roman Bath Life

A study of objects lost down the drains in the bathhouses from the Roman Empire reveals that people did all kinds of things there. They bathed, of course, but they also adorned themselves with trinkets, snacked on finger foods and even did needlework. "For the Romans, the baths weren't just a place to get clean, but this larger social center where a variety of activities were taking place," said study researcher Alissa Whitmore, a doctoral candidate in archaeology at the University of Iowa, who reported her findings at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in Seattle. [Source: livescience.com, January 18, 2013]

Livescience reported: “Whitmore examined drain finds from 11 public and military baths in Italy, Portugal, Switzerland, Germany and Britain, all dating between the first and fourth centuries. Unsurprisingly, she found strong evidence of objects related to bathing, such as perfume vials, nail cleaners, tweezers and flasks for holding oils and other pampering products. On the less-relaxing side of things, evidence shows medical procedures may have occasionally occurred in the baths, Whitmore found. Researchers found a scalpel lodged in one drain. And in the Caerleon baths in what is now Wales, archaeologists uncovered three adolescent and two adult teeth, suggesting bathhouse visitors may have undergone some dentistry, too.

“Visitors also took their meals in the baths, judging by the fragments of plates, bowls and cups found swept into drains. At Caerleon, bathers snacked on mussels and shellfish, Whitmore said, while baths in Silchester, in the United Kingdom, showed traces of poppy seeds. Bones left behind reveal that Roman bathers enjoyed small cuts of beef, mutton, goat, pork, fowl and wild deer. "Ancient texts talk about finger food and sweets, but don't really talk about animals," Whitmore said. "That was interesting to see." “Archaeologists have also found signs of gaming and gambling, including dice and coins, in various bathhouses. Perhaps most surprising, Whitmore said, researchers found bone and bronze needles and portions of spindles, suggesting that people did textile work in the baths. “This work likely wouldn't have happened in the water, she said, but in dressing rooms or common areas that had seating. The needles may have belonged to bathers who brought needlework to pass the time, or employees may have brought the sewing equipment, offering tailoring or other services at the sites while bathers relaxed, Whitmore said.

bath at Caracalla by Grundriss

“Among the sparkliest finds in the drains were pieces of jewelry. Archaeologists have found hairpins, beads, brooches, pendants and intaglios, or engraved gems, in bathhouse drains. A number of these finds definitely come from pool areas, Whitmore said. "It does seem that there's a fair amount of evidence for people actually wearing things into the water," she said. “Bathers may have held onto their jewelry in the pools to prevent the valuables from being stolen, Whitmore said. Or perhaps vanity inspired them. "It's really a place to see and be seen," Whitmore said. "It makes sense that even if you had to take off your fancy clothes, you would still show off your status through your fancy jewelry." Unfortunately, dips into hot and cold water would have loosened jewelry adhesives and caused metal settings to expand and contract. As a result, a number of unlucky Romans emerged from the baths considerably less bedecked than when they entered....One constant she's already found, she said, is the presence of women, even at baths on military bases. "It adds further evidence that Roman military forts aren't entirely these really masculine areas, but a much wider social atmosphere than we tend to give them credit for," Whitmore said.

Jewels Found in Bath Drains

Tom Metcalfe wrote in National Geographic: Dozens of carved gemstones depicting Roman gods and animals were discovered at Carlisle in the north of England, amid the ruins of an ancient drainage system that carried water away from public baths in the third and fourth centuries. Archaeologists announced the finds in June; it’s thought the gemstones were worn in jewelry by wealthy bathers, but that they fell into the drains when their settings loosened from the humidity and heat of the baths. [Source:Tom Metcalfe, National Geographic, December 6, 2023]

These gems include semiprecious stones of agate, jasper, amethyst, and carnelian; some are carved with images of Roman gods, such as Apollo, Venus, and Mars, while others show animals, such as rabbits and birds. Carved gemstones like this, called intaglios, were used by the Romans as a type of signature, often pressing a ring into clay or wax to create a seal. The ancient drains were found beneath a pavilion belonging to the Carlisle Cricket Club; the city was a regional center in Roman Britain, when it was known as Luguvalium.

Frank Giecco, the archaeologist who led the excavation, described the intaglios as "minuscule": The smallest measured about 0.2 inch in diameter (5 millimeters) while the largest topped out at about 0.6 inch (16 mm). "The craftsmanship to engrave such tiny things is incredible," he said. One piece of amethyst depicted the Roman goddess Venus holding either a flower or a mirror; a piece of jasper was engraved with a satyr lounging languidly on a bed of rocks, according to The Guardian.

According to Live Science Giecco thinks the bathers most likely had no clue that they lost their precious adornments until after they dried off and headed home, and even then, he wouldn't be surprised if they thought the disappearance was the result of petty theft rather than accidental loss. Bathhouse theft was so rampant that Roman baths elsewhere in England displayed "curse tablets" that "wished revenge on the perpetrators of such crimes," according to The Guardian. One such tablet read, "So long as someone, whether slave or free, keeps silent or knows anything about it, he may be accursed in blood, and eyes and every limb and even have all intestines quite eaten away if he has stolen the ring." [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, February 2, 2023]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024