Home | Category: Culture, Literature and Sports

NAUMACHIAE

Naumachiae were giant sea battles re-enacted in flooded arenas and basins in the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. Derived from the Ancient Greek word “naumachía”, literally "naval combat", naumachia refers to the staging of naval battles as mass entertainment and the water-filled area where the battles took place.

Edward Brooke-Hitching wrote: “In 46 B.C., on the orders of Julius Caesar, an enormous basin was dug in the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) outside the walls of Rome and filled with water. For this event (to celebrate the emperor’s recent Gallic, Alexandrian, Pontic, and African triumphs), two fleets of biremes, triremes, and quadremes, representing Tyre and Egypt, clashed in a battle of epic scale involving more than 6,000 prisoners who played the parts of soldiers and rowers. Also on record is the staged aquatic battle organized in 40 B.C. by Sextus Pompey for the entertainment of his troops that featured prisoners of war fighting to the death to celebrate his victory over Salvidienus Rufus and the occupation of Sicily. [Source: “Fox Tossing: And Other Forgotten and Dangerous Sports, Pastimes, and Games” by Edward Brooke-Hitching, Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, 2015]

Condemned criminals and captured prisoners of war fought to the death as they played out famous naval campaigns for the entertainment of a crowd. The events required sophisticated planning and execution, and as such were only performed with the approval of the emperor to mark special occasions. Fascination with the naumachia’s continued long after the last official Roman one was held. When interest in ancient Rome peaked the Renaissance, naumachiae were held, albeit in a less-ambitious form. In the mid-17th century, King Philip IV of Spain held one on the lake in the Buen Retiro palace in Madrid and another was held in the Spanish city of Valencia to celebrate the canonization of a local saint. In the early 1800s the theater of Sadlers Wells in London became famous for hosting naumachia-style spectacles strictly for entertainment. [Source María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, National Geographic History, September 27, 2017]

RELATED ARTICLES:

PUBLIC GAMES AND SHOWS OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: HISTORY, IMPORTANCE AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: LAYOUT, ARCHITEC europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Waters of War: The Naval Battles of the Roman Colosseum” by Michael R. Mathews Sr. (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Games: A Sourcebook (Blackwell) by Alison Futrell Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Spectacle in the Roman World” by Hazel Dodge (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Day Commodus Killed a Rhino: Understanding the Roman Games” (Witness to Ancient History) by Jerry Toner (2015) Amazon.com;

“Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Sourcebook” by Anne Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Donald G. Kyle Amazon.com;

“Public Spectacles in Roman and Late Antique Palestine” by Zeev Weiss Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“Game of Death in Ancient Rome: Arena Sport and Political Suicide” by Paul Plass (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Colosseum: Design - Construction - Events” by Nigel Rodgers (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Colosseum (Wonders of the World)” by Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard (Harvard University Press, 2005); Amazon.com;

“Roman Architecture” by Frank Sear (1998) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

Film “Gladiator”, with Russel Crowe, directed by Ridley Scott (2000) DVD Amazon.com;

Naumachiae in Gladiator II

Perhaps the most striking and unbelievable of the scenes in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator sequel is a recreation of a naumachia at the Colosseum. Alexander Larman wrote in The Telegraph: The epic conflict depicted on screen looks very much like a fantastical Hollywood invention, prompting the obvious question: did any of this really happen?

In fact, such an event did take place in the Colosseum, albeit probably just once. As classicist Dr Daisy Dunn tells me: “Roman emperors held ‘naval battles’ on special occasions, even before the Colosseum was built. These usually took place in special basins near the Tiber. They sometimes took place in wooden amphitheaters, too, and there’s a specific reference by the historian Cassius Dio (ca. 164–235) to Emperor Titus suddenly filling the Colosseum with water to host a surprise naval battle there.” It must have been feasible, says Dunn, but the precise logistics “continue to puzzle historians today.”[Source Alexander Larman, The Telegraph, July 10, 2024]

In the trailer for Gladiator II, Mescal’s character is shown battling not only nautical enemies but a warrior mounted on an armoured rhino — which also has some basis in fact. “It was incredibly rare that a rhino was shown in Rome, but one was led into the Colosseum in the first century AD,” says Dr Dunn. “It fought animals rather than gladiators — it was so unusual that the hope was that it would survive to be displayed again and again rather than be speared by a muscular man. ”

Why Naumachiae Were Held

The naumachiae appear to have combined entertainment with a demonstrations of imperial might designed to awe viewers with the sheer scale of the spectacle. María Engracia Muñoz-Santos wrote in National Geographic History: For all its theater, these events were not simulations. They were real battles, in which violence, mutilation, blood, and drowning made them as macabre a spectacle as a gladiator fight. To man the ships, the participants—known as naumachiarii—wore the uniforms of the two sides. They were typically prisoners of war or convicts who had been sentenced to death, though free men could take part, too. In fact, it is recorded that a praetor—a high-ranking official—participated in Caesar’s naumachia. [Source María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, National Geographic History, September 27, 2017]

The naumachia joined the ranks of existing Roman spectacles and entertainment, such as the gladiator fight (munus) and exotic animal hunt (venatio). These events attracted thousands of spectators from all social classes. Not only did they serve to amuse the public, they also served as a demonstration of power, of Rome’s preeminence in engineering, and the strength of its civilization.

The extensive planning required to stage the event explains why only around a dozen more were held after Caesar’s. A naumachia was massively expensive. Planners needed not only a colossal budget but also an appropriate site. They needed a crew of skilled craftsmen and engineers to create the theater, the seating, and the ships. They also needed a team to choreograph the action, and a sufficient number of participants to bring it to life.

Alexander Larman wrote in The Telegraph: There was a tradition in Ancient Rome of naumachiae taking place to commemorate famous victories or other notable national achievements. These extravaganzas were hugely expensive and time-consuming to organise, not least because the details had to be accurate in all respects to satisfy the bloodthirsty spectators. If, for instance, the Greek victory at Salamina against the Persians had to be staged, it was not only necessary to recreate both the Greek and Persian ships and arms as faithfully as possible, but also to build fortresses and to import everything from dolphins and seals to make the “sea” more authentic for the soldiers and sailors in these vast battles. [Source Alexander Larman, The Telegraph, July 10, 2024]

In their most benign form, the naumachiae were simply for show, with the participants being serving soldiers and sailors and the whole thing intended as little more than a pageant that would, not coincidentally, demonstrate the military strength and superiority of Rome to its would-be enemies. However, most of the time, the purpose behind them was lethal rather than simply ostentatious.

History of Naumachiae

Naumachiae are thought to date back to the third century B.C., when the Roman Gen. Scipio Africanus staged the re-enactments using his own troops, as mentioned by Suetonius in his Lives of the Twelve Caesars, and by Cassius Dio in his Roman History.[Source: “Fox Tossing: And Other Forgotten and Dangerous Sports, Pastimes, and Games” by Edward Brooke-Hitching, Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, 2015]

Alexander Larman wrote in The Telegraph: An early naumachia was staged in Rome in 46 B.C. in order to venerate Julius Caesar, who was celebrating a quadruple triumph during which he had simultaneously either conquered or put down rebellions in Gaul, Egypt, Numidia and Pontus. A common-or-garden commemoration would not suffice, and so something far grander, and more expensive, was offered instead. Amidst wild festivities that included everything from elephant battles to staged infantry combat, an artificial basin was constructed at the Campus Martius near the river Tiber, and water was diverted in order to flood it. Here, thousands of prisoners of war and criminals were gathered, placed in ships that would represent the battling Tyrian and Egyptian fleets, and then told to fight to the death. [Source Alexander Larman, The Telegraph, July 10, 2024]

About half a century later, Edward Brooke-Hitching wrote: “Together with his favored general, Marcus Agrippa, Emperor Augustus developed large areas of the Campus Martius for the sport, which included the Baths of Agrippa and also the Stagnum Agrippae (Lake of Agrippa), an ornamental body of water considerably larger than that dug by Julius Caesar, possessing dimensions of 1,800 by 1,200 (Roman) feet and located beside the River Tiber, with water piped in via a newly completed aqueduct. One of the grandest naumachiae ever mounted, though, was that of Claudius in A.D. 52. To mark the opening of a canal that was to later dry the Fucine Lake, a naval battle between Rhodes and Sicily was staged, consisting of 19,000 soldiers manning 100 ships.

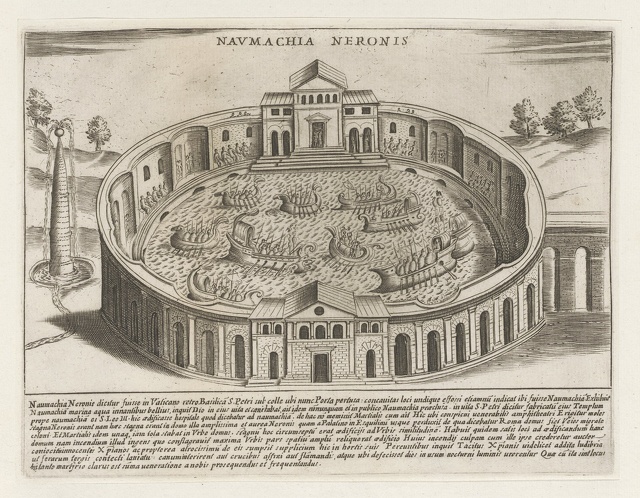

There would be other staged naumachiae decades later under the auspices of Nero, who constructed a wooden amphitheater in AD 57 for a multi-day extravaganza that involved combat on both land and sea, to say nothing of the slaughter of hippos and rhinos. Thanks to the latest advances in technology, the amphitheater could be drained immediately after the sea battle concluded for the land conflict.

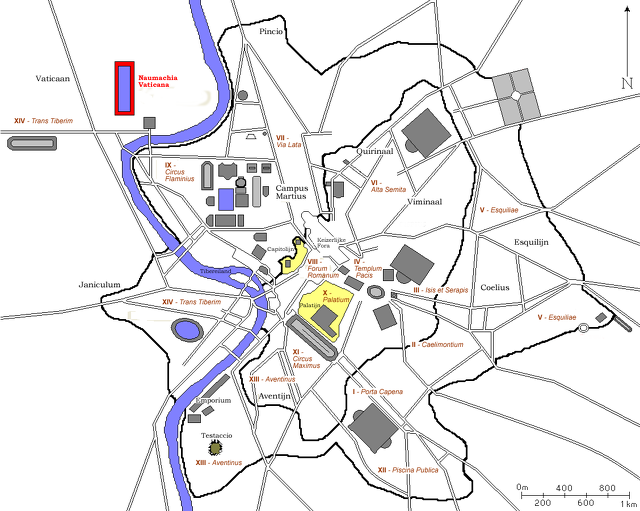

Later naumachiae, such as the one held by Trajan to celebrate his conquest of Dacia (modern-day Romania), are described. Trajan’s event took place in a pool near Vatican Hill, the remains of which were located in 18th-century excavations near the fortress of Sant’Angelo. It is believed the last mock naval battle of the Roman era was held in A.D. 248 to celebrate the millennium of Rome’s founding. It was ordered by Emperor Marcus Julius Philippus (Philip the Arabian) to celebrate the thousandth anniversary of Rome’s founding. Perhaps the Roman empire’s increasing weakness and financial strains were the reasons this was the last one.

Caesar’s Naumachia

María Engracia Muñoz-Santos wrote in National Geographic History: The people of Rome threw a party in 46 B.C. that would be remembered for many years to come. Julius Caesar had just returned, having crushed the followers of his great rival, Pompey the Great. Writing nearly two centuries later, the Roman historian Dio Cassius describes how in the first few days of his triumph the recently proclaimed dictator “proceeded homeward with practically the entire populace escorting him, while many elephants carried torches.”[Source María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, National Geographic History, September 27, 2017]

In addition to the excitement caused by the exhibition of a giraffe—dubbed a “camleopard” because it resembled a cross between a camel and leopard—Romans witnessed the preparations for another astonishing spectacle that would be the culmination of the festivities: a naval battle on a man-made lake built in the Campus Martius filled with water from the nearby Tiber River.

There, two fleets of biremes, triremes, and quadriremes with 4,000 galley slaves and 2,000 crew members on board clashed in a full-scale reconstruction of a naval battle. Roman historian Suetonius, writing in the first century A.D., recorded that people from all over Italy attended. Stalls were set up nearby and the streets filled with sex workers, thieves, and vendors. So many people tried to go that some slept in the street the night before to secure good seats.

During his time, Caesar’s naumachia was probably the most complex event held in ancient Rome. The naval battle was not merely a free-for-all, but a carefully staged portrayal of a historic battle between the fleets of Tyre and Egypt, two of Rome’s traditional enemies. Later naumachiae would reimagine historic battles between Athens and Persia, or Rhodes and Sicily. The crowds at Caesar’s event were so swept up by the bloodshed that hundreds were fatally trampled in the attempt to get a closer view of the action.. The poet Martial wrote: “Whatever is viewed in the Circus and the Amphitheater, that, Caesar, the wealth of your water has afforded you. So no more of Fucinus and the lake of direful Nero; let this be the only sea fight known to posterity.”

How Naumachiae Were Staged

Edward Brooke-Hitching wrote: “Little is known about the specifics of how the sea battles were conducted. Aquatic displays as a whole were popular at the time and included exhibitions of captured marine curiosities, water ballets, and pantomimes, so it is possible that the events were entirely theatrical. It is thought that two opposing fleets would face off, but as it is unclear how much of the action was pre-orchestrated, the events are categorized somewhere between sport and theatrical recreation. How fierce the battles were is also a mystery, although the fact that participants were usually facing imminent execution either way must have meant there was little motivation to participate enthusiastically. Indeed, Tacitus writes about Claudius being forced to dispatch the imperial guard on rafts during a naumachia in A.D. 52 to impel the two sides into fighting. [Source: “Fox Tossing: And Other Forgotten and Dangerous Sports, Pastimes, and Games” by Edward Brooke-Hitching, Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, 2015]

Alexander Larman wrote in The Telegraph: Everyone from convicted criminals to foreign enemies and captured slaves would be rounded up, placed alongside one another in vast vessels that were then launched into these artificial arenas, and told to fight to the death, on pain of an even more unpleasant fate if they refused. Their incentive — albeit one rarely made good on — was that, if victorious, they would be allowed to live to fight another day and even, in exceptional cases, be granted their freedom. This may have been enough to convince the participants to head into battle, but the baying hordes in the audience did not want to see mercy; they wanted to see blood. [Source Alexander Larman, The Telegraph, July 10, 2024]

They were seldom disappointed but Martial was. Although the sheer expense of the battle meant that no more were to be held for nearly half a century, the emperor Augustus staged another naumachia in 2 B.C. in order to mark the dedication of the Temple of Mars Ultor. Once again, the spectacle took place by the Tiber, and an aqueduct was newly constructed to flood the artificial basin, where 30 vessels and 3,000 men were pressed into recreating the conflict between the Athenian and Persian forces at the Battle of Salamis. While Augustus was delighted with the bloody spectacle, many were more distracted by the pop-up brothels and readily available sexual entertainment on hand. As the poet Ovid wrote in The Art of Love: “With such a throng, who could not fail to find what caught his fancy?”

Where Naumachiae Were Staged

Naumachiae were held at easily-flooded basins, natural bodies of water such as lakes and the Rhegium coast and at some amphitheaters. María Engracia Muñoz-Santos wrote in National Geographic History: In 40 B.C. one was organized in the Strait of Messina (between Sicily and Italy), on the orders of Sextus, Pompey’s younger son and enemy of Octavian (later Emperor Augustus). On this occasion, Sextus chose to re-create a recent battle: his own naval victory over Octavian. Sextus’s performance was even held in full view of his defeated rival as a calculated gesture of contempt. [Source María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, National Geographic History, September 27, 2017]

A century or so later Emperor Claudius staged his own mock sea battle—a portrayal of a historic battle between Sicily and Rhodes—on Fucine Lake in central Italy. One hundred boats and as many as 19,000 combatants (all convicts) took part in the extravaganza according to the historian Tacitus. To force them to fight, armed guards were stationed on pontoons around the lake. Tacitus recounts that although the battle was “one of criminals, it was contested with the spirit and courage of free men; and, after much blood had flowed, the combatants were exempted from destruction.”

The naumachia organized for Claudius on Fucine Lake in A.D. 52 was modeled after Augustus' extravaganza half a century earlier, but it did not go off as smoothly. A silver Triton emerged from the center of the lake and sounded trumpet to begin the battle. Before it started, the combatants cried, “Hail Caesar! We who are about to die salute you!” According to historian Suetonius, writing about 70 years later, the emperor replied, “Or not.” The convicts interpreted his words as a pardon and would not fight. Enraged at their reaction, Claudius leapt out of his seat and paced from one side of the lake to the other with his "ridiculous tottering gait." The participants were unmoved, so Claudius sent his imperial guard on rafts to prod the two sides into fighting. [Source María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, National Geographic History, September 27, 2017]

The most opulent naumachiae were held in Rome, but smaller ones were held throughout the empire in other parts of Italy and the provinces, such as Verona and Spain. A fourth-century inscription in the old Roman city of Emerita Augusta (Mérida, Spain) describes a structure that could be “flooded with water.” Mérida’s facilities, seen here, probably enabled the staging of lavish aquatic displays, but without the full-size ships used in Rome.

Staging Naumachia in Artificial Lakes and Amphitheaters

María Engracia Muñoz-Santos wrote in National Geographic History: Natural bodies of water might have been less expensive to use, but they were not as conducive to watching. And since watching was the fundamental purpose of these events, other theaters had to be created. The sight of a huge, specially dug lake, equipped with stands for spectators, would become an important part of the performance itself. [Source María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, National Geographic History, September 27, 2017]

Julius Caesar’s pioneering naumachia in the Campus Martius was held in a large, artificial lake that was filled in immediately after the battle had ended, probably to prevent the risk of disease from stagnant water. In 2 B.C. Augustus created an artificial lake of his own on the right bank of the Tiber River to hold a naumachia to celebrate the inauguration of the Temple of Mars Ultor in the Forum of Augustus. The Naumachia Augusti—the term “naumachia” was by then used to describe the body of water itself as well as the spectacle staged there—became regularly used for such events in Rome, at least until the end of the first century A.D.

Rather than excavating a lake, other emperors would flood amphitheaters with water. The first such recorded venue was pioneered during the reign of Nero, who organized a water battle in a stone and wood amphitheater he had built in the Campus Martius in A.D. 57. A few years later, Nero organized another naval show in the same amphitheater. Historians recorded great admiration at the amazing speed with which the site was not only filled, but also emptied in order to allow a wild animal hunt and gladiator games to take place on the same day. A few months later the structure burned to the ground during the Great Fire of Rome.

Colosseum Naumachiae

Alexander Larman wrote in The Telegraph: Nothing compared to the elaborate nature of the festivities staged for the construction of the Colosseum in B.C. 80, at the command of the emperor Titus. It proved to be an astonishingly difficult feat of engineering to flood the newly-built Colosseum, an activity that was estimated to take anything between 17 days and a month, and required the construction of an aqueduct that would connect the Tiber to the arena, filling it up to precisely the depth that would allow the extravaganza to take place, and then letting all hell break loose. [Source Alexander Larman, The Telegraph, July 10, 2024]

Titus held two naumachiae: one on an artificial lake created by Augustus and the other in the Colosseum itself. The historian Cassius Dio (ca. 164–235) describes the spectacle that ensued economically. “Titus suddenly filled this same theater with water and brought in horses and bulls and some other domesticated animals that had been taught to behave in the liquid element just as on land. He also brought in people on ships, who engaged in a sea-fight there, impersonating the Corcyreans and Corinthians.”

The recreation of the historic battle, including the creation of an artificial island, may have been popular as an idea, but the execution was stymied by the appearance of a violent rainstorm that not only led to the deaths of all the surviving combatants through drowning, but killed many of the spectators as well. Thereafter, the extraordinary expense and effort that went into such elaborate plans were dispensed with. Audiences seemed perfectly happy with land-bound gladiatorial spectacle instead, especially if some wild and exotic animals might be recruited for the fighting, too. The Colosseum therefore had subterranean tunnels and cells built beneath it that could house both human fighters and creatures alike, which meant that flooding the space would be impossible.

Did a Naumachiae Really Take Place at the Colosseum

Modern historians are still divided on whether naval battles actually took place in the Colosseum, despite there being historical accounts that they did. To see if it was physically possible to flood the arena, archaeologists have tried calculate how long it would take to fill it with enough water to conduct the event. [Source María Engracia Muñoz-Santos, National Geographic History, September 27, 2017]

During its first year, it was possible to flood the Colosseum with enough water for ships to sail. The the tunnels and storage rooms under the floor, the hypogeum, were built later, during the reign of Domitian. Constructed on the space left by the artificial lake beside the Domus Aurea (the Golden House, formerly Nero’s Palace), the low-lying Colosseum could be flooded and drained with relative ease, using a series of canals and pools.

Edward Brooke-Hitching wrote: “ The existing walls of the hypogea were first thought to disprove the idea, as they would obstruct such a thing from happening, but it has since been shown that the walls were added much later, possibly as late as the Middle Ages, and therefore the early form of the amphitheater would have been capable of holding the events. This is further supported by the discovery that the drains were built as part of the original foundation. “While excavations have still failed to turn up specific evidence of the naumachiae being staged in the Colosseum, such as remnants of ships or weapons used, ancient sources indicate that naumachiae did indeed take place. It is thought that for this to have been successful the ships involved must have been smaller in scale. [Source: “Fox Tossing: And Other Forgotten and Dangerous Sports, Pastimes, and Games” by Edward Brooke-Hitching, Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, 2015]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024