Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

LOVE BETWEEN HUSBAND AND WIFE IN ANCIENT ROME

One wife wrote her husband, who was away: "Send for me — if you don't I'll die without seeing you daily. How I wish I could fly and come to see you...It tortures me not to see you."

Another wife, whose husband had entered a sanctuary wrote him: "When I received your letter...in which you announce that you have become a recluse in the Sarapis temple at Memphis, I immediately thanked the gods that you are well, but you are not coming here when all other recluses have come home, I do not like this one bit.”

David Konstan, a classic professor at Brown University, told U.S. News and World Report: “ ”It was taken for granted that if the husband and wife treated each other properly, love would develop and emerge, and by the end of their lives it would be a deep, mutual feeling.” Displays of affection however were regarded with soem scorn. One senator was stripped of his seat because he embraced his wife in public.

On one epitaph a man wrote to his wife, apparently thanking her for help escaping capture for some crime: “You furnished most ample means for my escape. With your jewels you aided me when you took off all the gold and pearls from your person, and gave them over to me. And promptly, with slaves, money, and provisions, having cleverly deceived the enemies’ guards, you enriched my absence.”

See Separate Article: LOVE IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Marriage, Divorce, and Children in Ancient Rome” by Beryl Rawson (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Wedding: Ritual and Meaning in Antiquity” by Karen Hersh (2010)

Amazon.com;

“Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian”

by Susan Treggiari (1991) Amazon.com;

“The Discourse of Marriage in the Greco-Roman World” by Jeffrey Beneker and Georgia Tsouvala (2020) Amazon.com;

“Marriage, Sex and Death: The Family and the Fall of the Roman West” by Emma Southon (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Roman Household: A Sourcebook (Routledge) by Jane F. Gardner and Thomas Wiedemann (2013) Amazon.com;

“Women and the Law in the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook on Marriage, Divorce and Widowhood” (Routledge) by Judith Evans Grubbs (2002) Amazon.com;

“Women And Marriage During Roman Times Hardcover – May 22, 2010

by Maurice Pellison (1897) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1859-1912) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire”

by Jérôme Carcopino and Mary Beard (2003) Amazon.com

“As the Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History” by Jo-Ann Shelton, Pauline Ripat (1988) Amazon.com

“Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

“Secrets of Pompeii: Everyday Life in Ancient Rome” by Emidio De Albentiis, Alfredo Foglia (Photographer) Amazon.com;

Manus: Power of the Husband Over His Wife

Women were regarded as the property of a man. When they reached marriageable age they had two options: to be married with manu , which meant she belonged to her husband, or without manu , in which she still belonged to her father and could inherit wealth for him or be repossessed by him. The power over the wife possessed by the husband in its most extreme form, called by the Romans manus. By the oldest and most solemn form of marriage the wife was separated entirely from her father's family and passed into her husband's power or “hand” (conventio in manum). This assumes, of course, that he was sui iuris; if he was not, then she was, though nominally in his "hand," really subject, as he was, to his pater familias. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Any property she had of her own—and to have had any she must have been independent before her marriage—passed to her husband's father as a matter of course. If she had none, her pater familias furnished a dowry (dos), which shared the same fate, though it must be returned if she should be divorced. Whatever she acquired by her industry or otherwise while the marriage lasted also became her husband's (subject to the patria potestas under which he lived). So far, therefore, as property rights were concerned, manus differed in no respect from the patria potestas: the wife was in loco filiae, and on the husband's death took a daughter's share in his estate. |+|

“In other respects manus conferred more limited powers. The husband was required by law, not merely obliged by custom, to refer alleged misconduct of his wide to the iudicium domesticum, and this was composed in part of her cognates. He could put her away for certain grave offenses only; Romulus was said to have ordained that, if he divorced her without good cause, he should be punished with the loss of all his property. He could not sell her at all. In short, public opinion and custom operated even more strongly for her protection than for that of her children. It must be noticed, therefore, that the chief distinction between manus and patria potestas lay in the fact that the former was a legal relationship based upon the consent of the weaker party, while the latter was a natural relationship independent of all law and choice. |+|

Married Couple’s Sleeping Arrangements

On the first floor of one house excavated at Herculaneum have we discovered some cubicula with two beds. And in this case it seems more than probable thrt they belonged to an inn, so there is nothing to prove that the two beds were designed for a married couple. Literary texts give no hint of several beds together in one room except in the overcrowded cenacula (or sub-let) apartments of the insulae. Everywhere they record either the community of the lectus genialis or two separate rooms for the married pair. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

The couple made their choice of one or the other arrangement according to the space available in their house, that is to say, in the last analysis, according to their social standing. Humble folk and the modest middle classes had no room to spare in their homes and did not expect anything but a shared bed. In one of his epigrams Martial poses as being willing to accept the hand of a rich old woman, on the condition that they need never sleep together: "Communis tecum nee mihi lectus erit" But on the other hand he enlarged tenderly on the mutual affection which Calenus and Sulpicia preserved during the fifteen years of their married life, and dwelt without undue prudery on the amorous ecstasies which were witnessed by their nuptial bed and by the lamp "copiously sprinkled with the perfumes of Niceros."

The great aristocrats, however, organised their life in such a way that each of the married pair could enjoy independence in the home. Thus we always find Pliny the Younger alone in the room when he wakes "round about the first hour, rarely earlier, rarely later" ; in the silence and solitude and darkness which reign round his bed behind the closed shutters, he feels himself "wonderfully free and abstracted from those outward objects that dissipate attention and left to my own thoughts." This was his favorite time for composition. We must, however, imagine that his beloved Calpurnia was sleeping and getting up in another room, where he would join her when she was under his roof, and toward which his steps would turn of their own accord when she was absent.

It was evidently the right thing in the higher society of those days for man and wife to sleep apart, and the upstarts were not slow to copy the great in this matter. Petronius notes this eccentricity in his novel. Trimalchio swaggers in front of his guests, boasting the size of the house he has had built for himself. He has his own bedroom where he sleeps; his wife's he calls "the nest of this she-viper." But Trimalchio is deceiving either himself or us. Nature and habit are too strong for him; they reassert themselves at the gallop. In practice, one of the rooms ordered from the architect remains unused. Whatever he may pretend, he does not sleep by himself in haughty isolation, but shares in another room the bed of Fortunata.

Legal Oversight and Reforms of Marriage in Ancient Rome

Edward Gibbon wrote in the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”: “The ancient worship of the Romans afforded a peculiar goddess to hear and reconcile the complaints of a married life; but her epithet of Viriplaca, the appeaser of husbands, too clearly indicates on which side submission and repentance were always expected. Every act of a citizen was subject to the judgment of the censors; the first who used the privilege of divorce assigned, at their command, the motives of his conduct; and a senator was expelled for dismissing his virgin spouse without the knowledge or advice of his friends. Whenever an action was instituted for the recovery of a marriage portion, the proetor, as the guardian of equity, examined the cause and the characters, and gently inclined the scale in favor of the guiltless and injured party. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part IV,“Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

The dignity of marriage was restored by the Christians, who derived all spiritual grace from the prayers of the faithful and the benediction of the priest or bishop. The origin, validity, and duties of the holy institution were regulated by the tradition of the synagogue, the precepts of the gospel, and the canons of general or provincial synods; and the conscience of the Christians was awed by the decrees and censures of their ecclesiastical rulers. Yet the magistrates of Justinian were not subject to the authority of the church: the emperor consulted the unbelieving civilians of antiquity, and the choice of matrimonial laws in the Code and Pandects, is directed by the earthly motives of justice, policy, and the natural freedom of both sexes. [Source: Chapter XLIV: Idea Of The Roman Jurisprudence. Part IV,“Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Vol. 4, by Edward Gibbon, 1788, sacred-texts.com]

“Besides the agreement of the parties, the essence of every rational contract, the Roman marriage required the previous approbation of the parents. A father might be forced by some recent laws to supply the wants of a mature daughter; but even his insanity was not gradually allowed to supersede the necessity of his consent. The causes of the dissolution of matrimony have varied among the Romans; but the most solemn sacrament, the confarreation itself, might always be done away by rites of a contrary tendency. In the first ages, the father of a family might sell his children, and his wife was reckoned in the number of his children: the domestic judge might pronounce the death of the offender, or his mercy might expel her from his bed and house; but the slavery of the wretched female was hopeless and perpetual, unless he asserted for his own convenience the manly prerogative of divorce.

The warmest applause has been lavished on the virtue of the Romans, who abstained from the exercise of this tempting privilege above five hundred years: but the same fact evinces the unequal terms of a connection in which the slave was unable to renounce her tyrant, and the tyrant was unwilling to relinquish his slave.

Laws on Marriage and Children

<br/> Marcianus, Institutes, Book XVI: In the Thirty-fifth Section of the Lex Julia [a law of Augustus in 18BCE which made marriage a duty for Roman patricians], persons who wrongfully prevent their children, who are subject to their authority, to marry, or who refuse to endow them, are compelled by the proconsuls or governors of provinces, under a Constitution of the Divine Severus [r. 193-211] and Antoninus [ie Caracalla, r. 212-217], to marry or endow their said children. They are also held to prevent their marriage where they do not seek to promote it. [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329] [Lex Julia is an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the Julian family. Most often it refers to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 B.C., or to a law from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar]

<br/> Marcianus, Institutes, Book XVI: In the Thirty-fifth Section of the Lex Julia [a law of Augustus in 18BCE which made marriage a duty for Roman patricians], persons who wrongfully prevent their children, who are subject to their authority, to marry, or who refuse to endow them, are compelled by the proconsuls or governors of provinces, under a Constitution of the Divine Severus [r. 193-211] and Antoninus [ie Caracalla, r. 212-217], to marry or endow their said children. They are also held to prevent their marriage where they do not seek to promote it. [Source: “The Civil Law”, translated by S.P. Scott (Cincinnatis: The Central Trust, 1932), reprinted in Richard M. Golden and Thomas Kuehn, eds., “Western Societies: Primary Sources in Social History,” Vol I, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993), with indication that this text is not under copyright on p. 329] [Lex Julia is an ancient Roman law that was introduced by any member of the Julian family. Most often it refers to moral legislation introduced by Augustus in 23 B.C., or to a law from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar]

Paulus, On the Rescript of the Divine Severus and Commodus [r. 180-192]: It must be remembered that it is not one of the functions of a curator [legal guardian for a minor] to see that his ward is married, or not; because his duties only relate to the transaction of business. This Severus and Antoninus stated in a Rescript [a response to legal questions from officials] in the following words: "It is the duty of a curator to manage the affairs of his ward, but the ward can marry, or not, as she pleases.

Terentius Clemens, On the Lex Julia et Papia, Book III. [The Lex Papia of 9CE was treated with the Lex Julia. It tried to make Romans marry within their class]: A son under paternal control cannot be forced to marry.

Celsus, Digest, Book XV: Where a son, being compelled by his father, marries a woman whom would not have married if he had been left to the exercise of his own free will, the marriage will, nevertheless, legally be contracted; because it was not solemnized against the consent of the parties, and the son is held t have preferred to take this course.”

Childless Marriages in Ancient Rome

Whether because of voluntary birth control, or because of the impoverishment of the stock, many Roman marriages at the end of the first and the beginning of the second century were childless. The example of childlessness began at the top. The bachelor emperor Nerva, chosen perhaps for his very celibacy, was succeeded by Trajan and then by Hadrian, both of whom were married but had no legitimate issue. In spite of three successive marriages, a consul like Pliny the Younger produced no heir, and his fortune was divided at his death between pious foundations and his servants. The petite bourgeoisie was doubtless equally unprolific. It has certainly left epitaphs by the thousand where the deceased is mourned by his freedmen without mention of children. Martial seriously holds Claudia Rufina up to the admiration of his readers because she had three children; and we may consider as an exceptional case the matron of his acquaintance who had presented her husband with five sons and five daughters. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Perhaps women enjoyed the freedom of not having any children and among the upper classes, women were simply enjoying themselves [eropd. In his sixth satire Juvenal sketches for the amusement of his readers a series of portraits, not entirely caricatures, which show women quitting their embroidery, their reading, their song, and their lyre, to put their enthusiasm into an attempt to rival men, if not to outclass them in every sphere. There are some who plunge passionately into the study of legal suits or current politics, eager for news of the entire world, greedy for the gossip of the town and for the intrigues of the court, well-informed about the latest happening in Thrace or China, weighing the gravity of the dangers threatening the king of Armenia or of Parthia; with noisy effrontery they expound their theories and their plans to generals clad in field uniform (the paludamentum) while their husbands silently look on.

It is obvious that unhappy marriages must have been innumerable in a city where Juvenal as a matter of course adjures a guest whom he has invited to dinner to forget at his table the anxieties which have haunted him all day, especially those caused by the carryings on of his wife, who "is wont to go forth at dawn and to come home at night with crumpled hair and flushed face and ears."

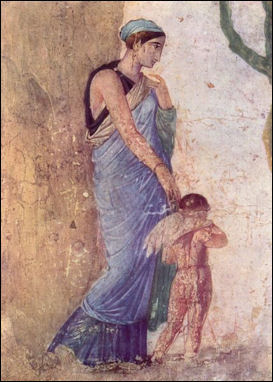

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024