Home | Category: Age of Caesar

JULIUS CAESAR’S EARLY MILITARY CAREER

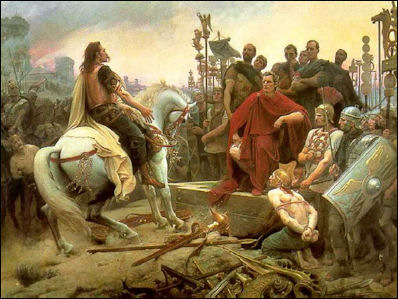

Siege of Alesia, Vercingetorix and Caesar Suetonius wrote: Caesar “served his first campaign in Asia on the personal staff of Marcus Thermus, governor of the province [81 B.C.]. Being sent by Thermus to Bithynia, to fetch a fleet, he dawdled so long at the court of Nicomedes that he was suspected of improper relations with the king; and he lent color to this scandal by going back to Bithynia a few days after his return, with the alleged purpose of collecting a debt for a freedman, one of his dependents. During the rest of the campaign he enjoyed a better reputation, and at the storming of Mytilene [80 BC] Thermus awarded him the civic crown [a chaplet of oak leaves, given for saving the life of a fellow-citizen, the highest military award of the Roman state]. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“He served too under Servilius Isauricus in Cilicia, but only for a short time; for learning of the death of Sulla, and at the same time hoping to profit by a counter-revolution which Marcus Lepidus was setting on foot, he hurriedly returned to Rome [78 BC]. But he did not make common cause with Lepidus, although he was offered highly favorable terms, through lack of confidence both in that leader's capacity and in the outlook, which he found less promising than he had expected.

“Then, after the civil disturbance had been quieted, he brought a charge of extortion against Cornelius Dolabella, an ex-consul who had been honored with a triumph [77 BC]. On the acquittal of Dolabella, Caesar determined to withdraw to Rhodes, to escape from the ill-will which he had incurred, and at the same time to rest and have leisure to study under Apollonius Molo, the most eminent teacher of oratory of that time. While crossing to Rhodes [74 BC], after the winter season had already begun, he was taken by pirates near the island of Pharmacussa and remained in their custody for nearly forty days in a state of intense vexation, attended only by a single physician and two body-servants; for he had sent off his travelling companions and the rest of his attendants at the outset, to raise money for his ransom. Once he was set on shore on payment of fifty talents, he did not delay then and there to launch a fleet and pursue the departing pirates, and the moment they were in his power to inflict on them the punishment which he had often threatened when joking with them. He then proceeded to Rhodes, but as Mithridates was devastating the neighboring regions, he crossed over into Asia, to avoid the appearance of inaction when the allies of the Roman people were in danger. There he levied a band of auxiliaries and drove the king's prefect from the province, thus holding the wavering and irresolute states to their allegiance.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JULIUS CAESAR (102-44 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR’S LIFE AND CHARACTER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR'S RISE AS A POLITICIAN: CICERO, CATO AND THE CATILINE CONSPIRACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, POMPEY AND CRASSUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, THE CROSSING OF THE RUBICON AND THE SITUATION IN ROME AT THE TIME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CIVIL WAR AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR’S DICTATORSHIP factsanddetails.com ;

ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: War Commentaries by Julius Caesar, M Univ, Internet Archive web.archive.org; War Commentaries Julius Caesar, MIT Classics classics.mit.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Caesar's Army: the Evolution, Composition, Tactics, Equipment & Battles of the Roman Army” by Harry Pratt Judson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2002) Amazon.com

“Caesar's Great Success: Sustaining the Roman Army on Campaign” by Alexander Merrow , Agostino von Hassell, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Greatest Victory: The Battle of Alesia, Gaul 52 BC” by John Sadler, Rosie Serdiville (2016) Amazon.com;

“Caesar Versus Pompey: Determining Rome’s Greatest General, Statesman & Nation-Builder” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2024) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Civil War: 49–44 BC” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2023) Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics Hardcover) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“Julius Caesar” by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library) Amazon.com;

“Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (2003) Amazon.com

“The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works : Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War : in One Volume, with Maps, Annotations, Appendices, and Encyclopedic Index” by 2017) Amazon.com

Caesar’s Military Skills

Suetonius wrote: “He was highly skilled in arms and horsemanship, and of incredible powers of endurance. On the march he headed his army, sometimes on horseback, but oftener on foot, bareheaded both in the heat of the sun and in rain. He covered great distances with incredible speed, making a hundred miles a day in a hired carriage and with little baggage, swimming the rivers which barred his path or crossing them on inflated skins, and very often arriving before the messengers sent to announce his coming. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“In the conduct of his campaigns it is a question whether he was more cautious or more daring, for he never led his army where ambuscades were possible without carefully reconnoitering the country, and he did not cross to Britannia without making personal inquiries about the harbors, the course, and the approach to the island. But on the other hand, when news came that his camp in Germania was beleaguered, he made his way to his men through the enemies' pickets, disguised as a Gaul. He crossed from Brundisium to Dyrrachium in winter time, running the blockade of the enemy's fleets; and when the troops which he had ordered to follow him delayed to do so, and he had sent to fetch them many times in vain, at last in secret and alone he boarded a small boat at night with his head muffled up; and he did not reveal who he was, or suffer the helmsman to give way to the gale blowing in their teeth, until he was all but overwhelmed by the waves.

“No regard for religion ever turned him from any undertaking, or even delayed him. Though the victim escaped as he was offering sacrifice, he did not put off his expedition against Scipio and Juba. Even when he had a fall as he disembarked, he gave the omen a favorable turn by crying: "I hold you fast, Africa." Furthermore, to make the prophecies ridiculous which declared that the stock of the Scipios was fated to be fortunate and invincible in that province, he kept with him in camp a contemptible fellow belonging to the Cornelian family, to whom the nickname Salvito had been given as a reproach for his manner of life.

“He joined battle, not only after planning his movements in advance but on a sudden opportunity, often immediately at the end of a march, and sometimes in the foulest weather, when one would least expect him to make a move. It was not until his later years that he became slower to engage, through a conviction that the oftener he had been victor, the less he ought to tempt fate, and that he could not possibly gain as much by success as he might lose by a defeat. He never put his enemy to flight without also driving him from his camp, thus giving him no respite in his panic. When the issue was doubtful, he used to send away the horses, and his own among the first, to impose upon his troops the greater necessity of standing their ground by taking away that aid to flight.

“He rode a remarkable horse, too, with feet that were almost human; for its hoofs were cloven in such a way as to look like toes. This horse was foaled on his own place, and since the soothsayers had declared that it foretold the rule of the world for its master, he reared it with the greatest care, and was the first to mount it, for it would endure no other rider. Afterwards, too, he dedicated a statue of it before the temple of Venus Genetrix.

Caesar’s Bravery

Suetonius wrote: “When his army gave way, he often rallied it single-handed, planting himself in the way of the fleeing men, laying hold of them one by one, and even catching them by the throat and forcing them to face the enemy; that, too, when they were in such a panic that an eagle-bearer made a pass at him with the point [the standard of the legion was a silver eagle with outstretched wings, mounted on a pole which had a sharp point at the other end, so that it could be set firmly in the ground] as he tried to stop him, while another left the standard in Caesar's hand when he would hold him back. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119] “His presence of mind was no less renowned, and the instances of it will appear even more striking. After the battle of Pharsalus, when he had sent on his troops and was crossing the strait of the Hellespont in a small passenger boat, he met Lucius Cassius, of the hostile party, with ten armored ships, and made no attempt to escape, but went to meet Cassius and actually urged him to surrender; and Cassius sued for mercy and was taken on board.

“At Alexandria, while assaulting a bridge, he was forced by a sudden sally of the enemy to take to a small skiff; when many others threw themselves into the same boat, he plunged into the sea, and after swimming for two hundred paces, got away to the nearest ship, holding up his left hand all the way, so as not to wet some papers which he was carrying, and dragging his cloak after him with his teeth, to keep the enemy from getting it as a trophy.

Caesar’s Control Over His Army

Suetonius wrote: “He valued his soldiers neither for their personal character nor their fortune, but solely for their prowess, and he treated them with equal strictness and indulgence; for he did not curb them everywhere and at all times, but only in the presence of the enemy. Then he required the strictest discipline, not announcing the time of a march or a battle, but keeping them ready and alert to be led on a sudden at any moment wheresoever he might wish. He often called them out even when there was no occasion for it, especially on rainy days and holidays. And warning them every now and then that they must keep close watch on him, he would steal away suddenly by day or night and make a longer march than usual, to tire out those who were tardy in following. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“When they were in a panic through reports about the enemy's numbers, he used to rouse their courage not by denying or discounting the rumours, but by falsely exaggerating the true danger. For instance, when the anticipation of Juba's coming filled them with terror, he called the soldiers together and said: "Let me tell you that within the next few days the king will be here with ten legions, thirty thousand horsemen, a hundred thousand light-armed troops, and three hundred elephants. Therefore some of you may as well cease to ask further questions or make surmises and may rather believe me, since I know all about it. Otherwise, I shall surely have them shipped on some worn out craft and carried off to whatever lands the wind may blow them."

“He did not take notice of all their offences or punish them by rule, but he kept a sharp look out for deserters and mutineers, and chastised them most severely, shutting his eyes to other faults. Sometimes, too, after a great victory he relieved them of all duties and gave them full licence to revel, being in the habit of boasting that his soldiers could fight well even when reeking of perfumes. In the assembly he addressed them not as "soldiers," but by the more fiattering term "comrades," and he kept them in fine trim, furnishing them with arms inlaid with silver and gold, both for show and to make them hold the faster to them in battle, through fear of the greatness of the loss. Such was his love for them that when he heard of the disaster to Titurius, he let his hair and beard grow long, and would not cut them until he had taken vengeance.

Roman soldiers setting up camp

“In this way he made them most devoted to his interests as well as most valiant. When he began the civil war, every centurion of each legion proposed to supply a horseman from his own savings, and the soldiers one and all offered their service without pay and without rations, the richer assuming the care of the poorer. Throughout the long struggle not one deserted and many of them, on being taken prisoner, refused to accept their lives, when offered them on the condition of consenting to serve against Caesar. They bore hunger and other hardships, both when in a state of siege and when besieging others, with such fortitude, that when Pompeius saw in the works at Dyrrachium a kind of bread made of herbs, on which they were living, he said that he was fighting wild beasts; and he gave orders that it be put out of sight quickly and shown to none of his men, for fear that the endurance and resolution of the foe would break their spirit. How valiantly they fought is shown by the fact that when they suffered their sole defeat before Dyrrachium, they insisted on being punished, and their commander felt called upon rather to console than to chastise them. In the other battles they overcame with ease countless forces of the enemy, though decidedly fewer in number themselves. Indeed one cohort of the sth legion, when set to defend a redoubt, kept four legions of Pompeius at bay for several hours, though almost all were wounded by the enemy's showers of arrows, of which a hundred and thirty thousand were picked up within the ramparts. And no wonder, when one thinks of the deeds of individual soldiers, either of Cassius Scaeva the centurion, or of Gaius Acilius of the rank and file, not to mention others. Scaeva, with one eye gone, his thigh and shoulder wounded, and his shield bored through in a hundred and twenty places, continued to guard the gate of a fortress put in his charge. Acilius in the sea-fight at Massilia grasped the stern of one of the enemy s ships, and when his right hand was lopped off, rivalling the famous exploit of the Greek hero Cynegirus, boarded the ship and drove the enemy before him with the boss of his shield.

“They did not mutiny once during the ten years of the Gallic war; in the civil wars they did so now and then, but quickly resumed their duty, not so much owing to any indulgence of their general as to his authority. For he never gave way to them when they were insubordinate, but always boldly faced them, discharging the entire ninth legion in disgrace before Placentia, though Pompey was still in the field, reinstating them unwillingly and only after many abject entreaties, and insisting on punishing the ringleaders.

“Again at Rome, when the men of the Tenth Legion clamored for their discharge and rewards with terrible threats and no little peril to the city, though the war in Africa was then raging, he did not hesitate to appear before them, against the advice of his friends, and to disband them. But with a single word, calling them "citizens," instead of 'soldiers," he easily brought them round and bent them to his will; for they at once replied that they were his "soldiers" and insisted on following him to Africa, although he refused their service. Even then he punished the most insubordinate by the loss of a third part of the plunder and of the land intended for them.”

Caesar’s Military Victories

Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: Between 58 and 50 B.C., his forces waged a series of campaigns in Gaul, conquering new territory for Rome and defeating several Gallic tribes. The climax of the Gallic Wars came in 52 B.C. when the Romans won the Battle of Alesia, defeating a confederation of tribes led by Gallic chief Vercingetorix. This victory was certainly worthy of a triumph. [Source, Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, July 10, 2019]

Caesar’s second great victory occurred in Egypt, shortly after Pompey’s death. Caesar traveled to Egypt, where Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy and sister Arsinoë were fighting for power. Caesar backed Cleopatra, and she defeated her siblings in 47 B.C. to become sole Egyptian ruler. Caesar’s third victory came later that year. Pharnaces II, king of Pontus, was crushed by Rome at the Battle of Zela in present-day Turkey.

Caesar scored a victory that led to the downfall of the remnants of Pompey’s forces, the defeat of King Juba I of Numidia in North Africa. During the Roman civil war, Juba supported the remnants of Pompey’s forces with reinforcements during the Battle of Thapsus (in present-day Tunisia) in April 46 B.C. Juba did die in the conflict, but he wasn’t slain by Caesar’s forces. Sources say that he and Marcus Petreius, a general allied with Pompey, fled and made a mutual suicide pact to avoid capture.

Not all of Caesar’s defeated enemies met such a fate. During the Egyptian triumph, Cleopatra’s sister Arsinoë was bound in chains. Her demeanor aroused the crowd’s sympathy. Sensitive to the feelings of the people, Caesar had her exiled to Ephesus rather than killed.

Caesar in Gaul

Gaul at the time of Caesar's arrival in 59 BC

In 58 B.C., Julius Caesar became governor and military commander of the Roman province of Gaul, which included modern France, Belgium, and portions of Switzerland, Holland, and Germany west of the Rhine, as well as parts of northern Italy. During his eight years there he led military campaigns involving both the Roman legions and tribes in Gaul who were often competing among themselves. One of the best sources on the period is Caesar's account, “Commentaries on the Gallic Wars,” originally published in 50 B.C.

In 59 B.C., after serving a year as consul, Caesar had himself named the governor of Gaul, where he distinguished himself as a superb organizer and a motivator of soldiers with whom he worked with, fought with and suffered with. He inspired such respect and affection from the men who served under him it was said they would do anything for him. Caesar personally selected Gaul for his province to govern. At that time the most forbidding part of the Roman territory. It was the home of barbarians, with no wealth like that of Asia, and few relics of a former civilization like those of Spain and Africa.

Caesar governed Gaul from 58 to 49 B.C. David Silverman of Reed College wrote: Caesar “chose for his province Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum, but the Senate added to this Transalpine Gaul, which as it turned out was where Caesar would spend most of his time, returning to the Italian side of the Alps periodically to meet with his people from the city and to keep his finger on what was happening on the domestic scene.” [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

See Separate Article: JULIUS CAESAR IN GAUL europe.factsanddetails.com

Caesar in Britain

Caesar invaded Britain twice. His conquests there are regarded as little more than the first steps of Rome’s effort to take over Britain. Britain did become fully Romanized until Emperor Claudius launched a more sustained campaign about a hundred years after Caesar’s invasion and that campaign was completed by Tacitus' father-in-law Agricola.

Dr Mike Ibeji wrote for the BBC: “The first Roman to seize the opportunities for glory provided by Britain was Julius Caesar. Having essentially conquered Gaul by 56 B.C., he found himself in a position where he was compelled to return to Rome and disband his army, unless he could find an excuse to stay in the field. He found that excuse in Britain. By claiming that the British tribes had helped the Gauls he had just cause to invade. In fact, as his own writings and the letters he sent to Cicero indicate, he was much more interested in the glory he would gain for crossing the Great Ocean and in the wealth of silver rumoured to be on the island, than in any so-called security risk. [Source: Dr Mike Ibeji, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

in 55 B.C., when Commius, king of the Atrebates, was ousted by Cunobelin, king of the Catuvellauni, and fled to Gaul. Caesar seized the opportunity to mount an expedition on behalf of Commius. He wanted to gain the glory of a victory beyond the Great Ocean, and believed that Britain was full of silver and booty to be plundered.

“His first expedition, however, was ill-conceived and too hastily organised. With just two legions, he failed to do much more than force his way ashore at Deal and win a token victory that impressed the senate in Rome more than it did the tribesmen of Britain. In 54 B.C., he tried again, this time with five legions, and succeeded in re-establishing Commius on the Atrebatic throne. Yet he returned to Gaul disgruntled and empty-handed, complaining in a letter to Cicero that there was no silver or booty to be found in Britain after all.” |::|

By the time of the second expedition in 54 B.C. “he had received the accolades he desired and ...pulled out of the island, exacting tribute and hostages and concentrated on pacifying the troublesome tribes of Gaul before crossing the Rubicon with his army and returning to Rome as its most powerful son. His power and prestige were so great, in fact, that his enemies were forced to assassinate him, sparking the civil war that destroyed the Republic. |::|

See Separate Article: JULIUS CAESAR IN BRITAIN europe.factsanddetails.com

Caesar’s Massacre of Germanic Tribes at the Rhine

According to the Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Caesar’s firsthand account of his campaign against Germanic tribes in the Rhine region, two tribes — the Tencteri and Usipetes — crossed the Rhine River in 55 B.C. and petitioned Caesar to allow them to settle in Gaul. After negotiations collapsed and the Germans attacked his cavalry, Caesar directed his entire army of eight legions against the German camp, killing 150,000 to 200,000 men, women, and children. [Source:Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2016]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Dutch archaeologists have examined archaeological, historical, and geochemical data to pinpoint the site of a catastrophic battle between Julius Caesar and two Germanic tribes,the Tencteri and Usipetes. The recent study analyzed a deposit of metal artifacts and human skeletal remains that was retrieved during dredging of the Meuse River near the village of Kessel in the Netherlands. The mass of first-century B.C. weaponry, including swords, spearheads, and helmets, as well as the condition and radiocarbon dates of the bones, seem to confirm the site of the slaughter.

Some of the skeletal remains bear holes and other marks of violent trauma. Scholars believe that the Romans may have dumped the battlefield remnants in the river after the fight. Geochemical analysis of the dental enamel of three individuals also indicates that they were not native to the Dutch river area, confirming Caesar’s own account that the Tencteri and Usipetes had emigrated from somewhere east of the Rhine. “This research is important because it not only contributes to a better understanding of the military history of Caesar’s Germanic campaigns,” says Nico Roymans of VU University Amsterdam, “but it also informs us about the highly violent nature of the Roman conquest, including cases of genocide, and the dramatic impact it must have had on the indigenous societies in this frontier zone.”

Caesar Versus Vercingetorix

In 52 B.C., Caesar put down the last great Gallic-Celtic uprising. Vercingetorix, the leader of the Gallic-Celtic forces, surrendered himself at the feet of Caesar who sent him to Rome where the Gallic leader was imprisoned for six years and then paraded through the streets and strangled in the Forum.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “In 52 B.C. Caesar faced his most formidable Gallic opponent in Vercingetorix, a resourceful general whose initial successes induced almost all of the Gallic tribes to align themselves with him. The decisive victory came with the fall of the Gallic stronghold at Alesia (near modern Troyes; cf. Plut. Caes. 27) in 51, just in time to allow Caesar to turn his attentions to domestic affairs. By now the number of legions under Caesar's command had risen to 10, augmented by large contingents of Gallic auxiliaries (light-armed) and cavalry. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

With the defeat of Vercingetorix, the conquest of Gaul was then completed. A large part of the population had been either slain in war or reduced to slavery. The new territory was pacified by bestowing honors upon the Gallic chiefs, and self-government upon the surviving tribes. The Roman legions were distributed through the territory; but Caesar established no military colonies like those of Sulla. The Roman arts and manners were encouraged; and Gaul was brought within the pale of civilization. \~\

Battle of Alesia: Caesar Victory Over Vercingetorix

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “He having disposed his army in several bodies, and set officers over them, drew over to him all the country round about as far as those that lie upon the Arar, and having intelligence of the opposition which Caesar now experienced at Rome, thought to engage all Gaul in the war. Which if he had done a little later, when Caesar was taken up with the civil wars, Italy had been put into as great a terror as before it was by the Cimbri. But Caesar, who above all men was gifted with the faculty of making the right use of everything in war, and most especially of seizing the right moment, as soon as he heard of the revolt, returned immediately the same way he went, and showed the barbarians, by the quickness of his march in such a severe season, that an army was advancing against them which was invincible. For in the time that one would have thought it scarce credible that a courier or express should have come with a message from him, he himself appeared with all his army, ravaging the country, reducing their posts, subduing their towns, receiving into his protection those who declared for him.

Till at last the Edui, who hitherto had styled themselves brethren to the Romans, and had been much honoured by them, declared against him, and joined the rebels, to the great discouragement of his army. Accordingly he removed thence, and passed the country of the Ligones, desiring to reach the territories of the Sequani, who were his friends, and who lay like a bulwark in front of Italy against the other tribes of Gaul. There the enemy came upon him, and surrounded him with many myriads, whom he also was eager to engage; and at last, after some time and with much slaughter, gained on the whole a complete victory; though at first he appears to have met with some reverse, and the Aruveni show you a small sword hanging up in a temple, which they say was taken from Caesar. Caesar saw this afterwards himself, and smiled, and when his friends advised it should be taken down, would not permit it, because he looked upon it as consecrated. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“After the defeat, a great part of those who had escaped fled with their king into a town called Alesia, which Caesar besieged, though the height of the walls, and number of those who defended them, made it appear impregnable; and meantime, from without the walls, he was assailed by a greater danger than can be expressed. For the choice men of Gaul, picked out of each nation, and well armed, came to relieve Alesia, to the number of three hundred thousand; nor were there in the town less than one hundred and seventy thousand. So that Caesar being shut up betwixt two such forces, was compelled to protect himself by two walls, one towards the town, the other against the relieving army, as knowing if these forces should join, his affairs would be entirely ruined. The danger that he underwent before Alesia justly gained him great honour on many accounts, and gave him an opportunity of showing greater instances of his valour and conduct than any other contest had done.

One wonders much how he should be able to engage and defeat so many thousands of men without the town, and not be perceived by those within, but yet more, that the Romans themselves, who guarded their wall which was next to the town, should be strangers to it. For even they knew nothing of the victory, till they heard the cries of the men and lamentations of the women who were in the town, and had from thence seen the Romans at a distance carrying into their camp a great quantity of bucklers, adorned with gold and silver, many breastplates stained with blood, besides cups and tents made in the Gallic fashion. So soon did so vast an army dissolve and vanish like a ghost or dream, the greatest part of them being killed upon the spot. Those who were in Alesia, having given themselves and Caesar much trouble, surrendered at last; and Vergentorix, who was the chief spring of all the war, putting his best armour on, and adorning his horse, rode out of the gates, and made a turn about Caesar as he was sitting, then quitting his horse, threw off his armour, and remained quietly sitting at Caesar's feet until he was led away to be reserved for the triumph.”

Siege of Alesia

Caesar-Era Gallic Outpost in Germany

In 2012, archaeologists announced that they had found the remains of a Caesar-era military camp in Germany. Andrew Curry wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The discovery of a collection of 75 sandal nails has led German archaeologists to the rare identification of a temporary Roman military camp near the town of Hermeskeil, near Trier, in southwestern Germany. Directed by Sabine Hornung, an archaeologist at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, the team uncovered the camp’s main gate, the flat stones that once paved its entrance, and grindstones used by the Romans to mill grain. Scattered among the paving stones were bits of metal that the team quickly identified as sandal nails. Some of the nails were quite large—as much as an inch across— and had distinct workshop marks of a type used by the army, “a sort of cross with little dots” or studs, says Hornung. “That told us it was definitely a military camp,” she adds. Ground-penetrating radar surveys showed that the camp, built to house soldiers on the move, sprawls over nearly 65 acres. [Source: Andrew Curry, Archaeology, December 6, 2012 ]

“Excavated pottery sherds, both from local and imported Roman wares, date the camp to the 50s B.C., the period Julius Caesar wrote about in his memoir, The Gallic Wars. From 58 to 50 B.C., Caesar waged three campaigns against the Gallic tribes and their powerful leaders for control over the territory of Gaul, primarily modern-day France and Belgium. Taking account of the camp’s date and the distinctly Caesarean sandal nails, Hornung says, “It’s very probable it is a camp built by Julius Caesar’s legions.”

“The camp sits just a few miles away from the so-called “Hunnenring,” a major Celtic hill fort with 30-foot-high walls. Such centers of military and political power made Gaul an attractive target for the Romans. By focusing their efforts on these regional centers, the Romans could exert sustained and concentrated pressure on local leaders instead of having to chase down the scattered tribes living in the German forests further to the east. Eventually this pressure, and the military victories achieved by Caesar and his legions, resulted in the conquest of Gaul and cleared the way for the general to assume sole control of the Roman Republic. For Gunter Moosbauer, an archaeologist at Germany’s University of Osnabrück familiar with the discovery, the finds from Hermeskeil are an “archaeological thrill.” He says, “Roman field campaigns lasted just a few months, and to find one of their temporary camps is really rare."

Surrender of Vercingetorix

Ancient Roman 'Spike Defenses' Made Famous by Julius Caesar Found in Germany

In February 2023, archaeologists announced that they had found Roman-era wooden spikes like the kind used by Caesar preserved in the damp soil in the Bad Ems area of Germany. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science: In 52 B.C., Julius Caesar used an ingenious system of ditches and stakes to defend his soldiers from an encroaching Gallic army in modern-day central France. More than two millennia later, archaeologists have discovered the first preserved example of similar defensive stakes, which likely protected an ancient silver mine. A student team made the unprecedented discovery in the area of Bad Ems, halfway between the present-day cities of Bonn and Mainz in Germany, on the former northern border of the Roman Empire. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science, February 28, 2023]

Archaeologists have been working in the area of Bad Ems since the late 19th century. Early excavations yielded processed silver ore along with wall foundations and metal slag, so researchers believed that they comprised smelting works dating to the early second century A.D. But in 2016, a hunter noticed odd crop formations and told archaeologists at Goethe University, who later found that the area hosted a 20-acre (8 hectares) double-ditched Roman camp with the remains of around 40 wooden watchtowers.

In 2023, the student team led by Frederic Auth unearthed the preserved wooden spikes in the damp soil of Blöskopf Hill, which held a second recently discovered Roman camp 1.3 miles (2 kilometers) away from the first fort. The team also found a coin from A.D. 43, proving that the two forts significantly pre-dated a larger system of fortifications known as the "limes" that was constructed in A.D. 110. The limes (meaning "boundary line") was the fortified border wall that ran along the northern Roman Empire.

The ancient Roman historian Tacitus offered clues to what the two forts were defending: He noted that a Roman governor named Curtius Rufus tried to mine silver in this area in A.D. 47, but found little. In reality, Bad Ems had plenty of silver — around 200 tons of it were found centuries later — but the Romans did not dig deep enough to get to it. It is possible that the Romans set up camp to defend themselves from raids as they tried to mine this important raw material, the archaeologists said.

While Julius Caesar died long before the forts at Bad Ems were set up, his strategy of creating a ditch-and-spike defensive system outlived him. In his book "Gallic Wars," Caesar wrote about the fortifications he set up in the Battle of Alesia in France in 52 B.C. He wanted his camp to be defended by as few soldiers as possible, so he cut down very thick branches, sharpened them to a point, and sank them into trenches, fastening them firmly at the bottom and covering the ditch with willow branches and twigs. "Whoever entered within them were likely to impale themselves on very sharp stakes," Caesar wrote.

In spite of the well-preserved finds at Bad Ems, mysteries remain surrounding the forts' use. The larger fort was never fully completed, and both forts appear to have been purposefully burned down a few years after their construction. Further research is needed to determine whether the researchers' hypothesis about the forts defending silver mines is correct, Markus Scholz, a professor of Roman archaeology at Goethe University, said in a statement.

Triumphs of Caesar

Julius Caesar received an unprecedented four triumphs — for his victories in Gaul, Egypt, Pontus and Numidia in North Africa. Andrea Frediani wrote in National Geographic History: Over the course of a few weeks in 46 B.C., Caesar staged his four triumphs, beginning with the Gallic. Historians say it started with a curious incident. The first-century A.D. Roman historian Suetonius described how Caesar’s chariot broke as he paraded through city. The general nearly fell, but continued along the route “between two lines of elephants, forty in all, which acted as his torch bearers.” [Source, Andrea Frediani, National Geographic History, July 10, 2019]

Caesar’s triumphs were exceptional not only for their immense expense and grand scale, but also for the fact that he was the only person in Rome’s history to receive four, one for each of his victorious campaigns. By celebrating Caesar, Rome was also celebrating itself, because this general had enlarged and enriched the republic like no other man before him. The one who came closest was Caesar’s ally turned rival, Pompey the Great. He had received three triumphs. Although past triumphs were not the focus of Caesar’s plans, they had set a high bar, which Caesar was set to overcome with great flair.

In the Gallic triumph, Caesar’s men followed behind him. Some carried large placards depicting the most important battles and events. It was customary for them to carouse, singing songs meant to stave off the jealousy of the gods by making fun of the general’s vices. Suetonius recorded a particularly risque verse that poked fun at Caesar’s love affairs:

Home we bring our bald whoremonger; Romans, lock your wives away!

All the bags of gold you lent him

Went his Gallic tarts to pay.

See Separate Article: TRIUMPHS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024