Home | Category: Age of Caesar

ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR

In 44 B.C., after declaring himself “Dictator for Life”, Caesar was crowned with a royal diadem at a religious ceremony, ushering in the era of imperial Rome. Many Romans were appalled by Caesar's audacious seizure of power and riled further when he placed a statue with his likeness next to statues of the founders of Rome. Almost immediately members of the Senate began plotting against him.

On the ides of March (March 15, 44, B.C.), a month after he proclaimed himself Dictator for Life, 55-year-old Caesar was assassinated on the floor of the Senate by Brutus and Cassius, an event recounted in a famous Shakespeare play.

The assassination was at least in part a display of contempt against Caesar’s ruthless impoundment of power and rumors that he was planning to rule the Roman Empire with Cleopatra from Alexandria. Brutus, a close friend of Caesar, and Cassius, the mastermind of the conspiracy, recruited 20 Senators and 40 other conspirators, including many people who had been loyal to Caesar. They ones that planned to participate in the killing carried daggers concealed under their cloaks.

Caesar’s last words, reportedly were “Et tu, Brute,” (“And you, Brutus”), said to be an allusion to hsi friend Brutus betraying him. But, Jamie Frater wrote for Listverse, “Caesar’s last words were actually “And you also” as recorded (in Greek) by Suetonius:(kai su teknon). These words were spoken to Brutus, which is undoubtedly the reason that Shakespeare coined the phrase:“And you, Brutus”. The meaning of his last words is unknown – but it would seem fair to think that he was telling his murderer: “you will be next”. Caesar was bi-lingual (Greek and Latin) and Greek was the dominant language in Rome at the time, so it is not unreasonable that his last words would have been uttered in that language. [Source: Jamie Frater, Listverse, May 5, 2008]

RELATED ARTICLES:

AFTER THE ASSASSINATION OF JULIUS CAESAR europe.factsanddetails.com ;

OCTAVIAN AND MARK ANTONY AFTER CAESAR’S DEATH factsanddetails.com

JULIUS CAESAR (102-44 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR’S LIFE AND CHARACTER europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR'S RISE AS A POLITICIAN: CICERO, CATO AND THE CATILINE CONSPIRACY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

JULIUS CAESAR'S MILITARY CAREER: SKILLS, LEADERSHIP, VICTORIES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, POMPEY AND CRASSUS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR, THE CROSSING OF THE RUBICON AND THE SITUATION IN ROME AT THE TIME europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CIVIL WAR AFTER CAESAR CROSSES THE RUBICON europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAESAR’S DICTATORSHIP factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People's History of Ancient Rome” by Michael Parenti Amazon.com;

“Julius Caesar” by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library) Amazon.com;

“The Ides: Caesar's Murder and the War for Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2010) Amazon.com;

“Julius Caesar: The Life and Times of the People’s Dictator” by Luciano Canfora, Stuart Midgley Marian Hill (2007) Amazon.com;

“Caesar: Politician and Statesman” by Mattias Gelzer, Peter Needham (1968) Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (2003) Amazon.com

“The Civil War of Caesar” (Penguin Classics) by Julius Caesar and Jane P. Gardner Amazon.com;

“Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell into Tyranny” by Edward Watts (2020), Illustrated Amazon.com;

“The Fall of the Roman Republic: Roman History, Books 36-40 (Oxford World's Classics)

by Cassius Dio Amazon.com;

“Fall of the Roman Republic (Penguin Classics) by Plutarch Amazon.com;

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics Hardcover) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works : Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War : in One Volume, with Maps, Annotations, Appendices, and Encyclopedic Index” by 2017) Amazon.com

“SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” by Mary Beard (2015) Amazon.com

“A Companion to the Roman Republic” by Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Editor) Amazon.com;

“Roman Republics” by Harriet I. Flower (2009) Amazon.com

Julius Caesar’s Assassins and Conspirators

The leading conspirators were Brutus (Marcus Junius Brutus, a leading politician and friend of Caesar) and Cassius (Gaius Cassius Longinus, a Roman senator, and the brother in-law of Brutus). They and the other men who conspired to kill Caesar were men who had received special favors from him. Brutus and Cassius had both served in Pompey’s army, and had been pardoned by Caesar and promoted to offices under his government.

Suetonius wrote: “It was this that led the conspirators to hasten in carrying out their designs, in order to avoid giving their assent to this proposal. Therefore the plots which had previously been formed separately, often by groups of two or three, were united in a general conspiracy, since even the populace no longer were pleased with present conditions, but both secretly and openly rebelled at his tyranny and cried out for defenders of their liberty. On the admission of foreigners to the Senate, a placard was posted: "God bless the Republic! let no one consent to point out the Senate to a newly made senator."

The following verses too were sung everwhere:

'Caesar led the Gauls in triumph, led them to the senate house;

Then the Gauls put off their breeches, and put on the latus clavus.'' [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“When Quintus Maximus, whom he had appointed consul in his place for three months, was entering the theater, and his lictor called attention to his arrival in the usual manner, a general shout was raised: "He's no consul!" At the first election after the deposing of Caesetius and Marullus, the tribunes, several votes were found for their appointment as consuls. Some wrote on the base of Lucius Brutus' statue, "Oh, that you were still alive"; and on that of Caesar himself: 'First of all was Brutus consul, since he drove the kings from Rome; Since this man drove out the consuls, he at last is made our king."

“More than sixty joined the conspiracy against him, led by Gaius Cassius and Marcus and Decimus Brutus. At first they hesitated whether to form two divisions at the elections in the Campus Martius, so that while some hurled him from the bridge [the pons suffragiorum, a temporary bridge of planks over which the voters passed one by one, to cast their ballots] as he summoned the tribes to vote, the rest might wait below and slay him; or to set upon him in the Via Sacra or at the entrance to the theater. When, however, a meeting of the Senate was called for the Ides of March in the curia adjoining the Theater of Gnaeus Pompeius, they readily gave that time and place the preference.”

Brutus and Cassius

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Marcus Brutus, who, by his father’s side, was thought to be descended from that first Brutus, and by his mother’s side from the Servil, another noble family, being besides nephew and son-in-law to Cato. But the honors and favors he had received from Cæsar, took off the edge from the desires he might himself have felt for overthrowing the new monarchy. For he had not only been pardoned himself after Pompey’s defeat at Pharsalia, and had procured the same grace for many of his friends, but was one in whom Cæsar had a particular confidence. He had at that time the most honorable prætorship of the year, and was named for the consulship four years after, being preferred before Cassius, his competitor. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Upon the question as to the choice, Cæsar, it is related, said that Cassius had the fairer pretensions, but that he could not pass by Brutus. Nor would he afterwards listen to some who spoke against Brutus, when the conspiracy against him was already afoot, but laying his hand on his body, said to the informers, “Brutus will wait for this skin of mine,” intimating that he was worthy to bear rule on account of his virtue, but would not be base and ungrateful to gain it. Those who desired a change, and looked on him as the only, or at least the most proper, person to effect it, did not venture to speak with him; but in the nighttime laid papers about his chair of state, where he used to sit and determine causes, with such sentences in them as, “You are asleep, Brutus,” “You are no longer Brutus.” Cassius, when he perceived his ambition a little raised upon this, was more instant than before to work him yet further, having himself a private grudge against Cæsar, for some reasons that we have mentioned in the Life of Brutus. Nor was Cæsar without suspicions of him, and said once to his friends, “What do you think Cassius is aiming at? I do n’t like him, he looks so pale.” And when it was told him that Antony and Dolabella were in a plot against him, he said he did not fear such fat, luxurious men, but rather the pale, lean fellows, meaning Cassius and Brutus.

Brutus

“In this juncture, Decimus Brutus, surnamed Albinus, one whom Cæsar had such confidence in that he made him his second heir, who nevertheless was engaged in the conspiracy with the other Brutus and Cassius, fearing lest if Cæsar should put off the senate to another day, the business might get wind, spoke scoffingly and in mockery of the diviners, and blamed Cæsar for giving the senate so fair an occasion of saying he had put a slight upon them, for that they were met upon his summons, and were ready to vote unanimously, that he should be declared king of all the provinces out of Italy, and might wear a diadem in any other place but Italy, by sea or land. If any one should be sent to tell them they might break up for the present, and meet again when Calpurnia should chance to have better dreams, what would his enemies say? Or who would with any patience hear his friends, if they should presume to defend his government as not arbitrary and tyrannical? But if he was possessed so far as to think this day unfortunate, yet it were more decent to go himself to the senate, and to adjourn it in his own person. Brutus, as he spoke these words, took Cæsar by the hand, and conducted him forth. He was not gone far from the door, when a servant of some other person’s made towards him, but not being able to come up to him, on account of the crowd of those who pressed about him, he made his way into the house, and committed himself to Calpurnia, begging of her to secure him till Cæsar returned, because he had matters of great importance to communicate to him. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Artemidorus, a Cnidian, a teacher of Greek logic, and by that means so far acquainted with Brutus and his friends as to have got into the secret, brought Cæsar in a small written memorial, the heads of what he had to depose. He had observed that Cæsar, as he received any papers, presently gave them to the servants who attended on him; and therefore came as near to him as he could, and said, “Read this, Cæsar, alone, and quickly, for it contains matter of great importance which nearly concerns you.” Cæsar received it, and tried several times to read it, but was still hindered by the crowd of those who came to speak to him. However, he kept it in his hand by itself till he came into the senate. Some say it was another who gave Cæsar this note, and that Artemidorus could not get to him, being all along kept off by the crowd.

Motivations for the Assassination of Julius Caesar

It has been said that the murder of Caesar was the most senseless act that the Romans ever committed. His death deprived Rome of the greatest man she ever produced. Some have suggested that the murderers probably believed they were acting on the behalf of Roman democracy but their act did not destroy the work of Caesar.

Caesar is said have failed to adjust himself sufficiently to the conservative spirit of the time. There were still living at Rome men who were blindly attached to the old republican forms. To them the reforms of Caesar looked like a work of destruction, rather than a work of creation. They saw in his projects a scheme for reviving the kingship. It was said that when Caesar was offered a crown he looked at it wistfully; and that he had selected his nephew Octavius as his royal heir. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “To understand the multiplicity of the motives of the conspirators who stabbed Caesar to death on March 15th, 44, one should remember that Caesar was just about to set off for the far east, to recover the standards lost by Crassus and avenge the defeat at Carrhae in 53. Some no doubt acted from pure and high-minded Catonian principle, to end the tyranny and restore the Republic, although by 44 anyone who thought that the dominance of the senatorial oligarchy could be reconstituted by the elimination of Caesar must be thought naively idealistic. Others may have been outraged by Caesar's having set up his mistress, Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, in his villa across the Tiber. But more urgent than any of these was the virtual certainty that soon after Caesar left the country Rome would see a repetition of what had happened when Sulla left to fight Mithradates, despite the fact that Caesar had tried to appoint hand-picked magistrates for the three years which he estimated he would need to conquer the Parthians. That would help to explain why the conspirators were such a mixed bag, some (such as Cassius and Brutus) former Pompeians, others long time partisans of Caesar himself.” [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Signs That the Assassination of Caesar Was Coming

Suetonius wrote: “Now Caesar's approaching murder was foretold to him by unmistakable signs. A few months before, when the settlers assigned to the colony at Capua by the Julian Law were demolishing some tombs of great antiquity, to build country houses, and plied their work with the greater vigor because as they rummaged about they found a quantity of vases of ancient workmanship, there was discovered in a tomb, which was said to be that of Capys, the founder of Capua, a bronze tablet, inscribed with Greek words and characters to this purport: "Whenever the bones of Capys shall be moved, it will come to pass that a son of llium shall be slain at the hands of his kindred, and presently avenged at heavy cost to Italia." And let no one think this tale a myth or a lie, for it is vouched for by Cornelius Balbus, an intimate friend of Caesar. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“Shortly before his death, as he was told, the herds of horses which he had dedicated to the river Rubicon when he crossed it, and had let loose without a keeper, stubbornly refused to graze and wept copiously. Again, when he was offering sacrifice, the soothsayer Spurinna warned him to beware of danger, which would come not later than the Ides of March; and on the day before the Ides of that month a little bird called the king-bird flew into the Curia of Pompeius with a sprig of laurel, pursued by others of various kinds from the grove hard by, which tore it to pieces in the hall. In fact the very night before his murder he dreamt now that he was flying above the clouds, and now that he was clasping the hand of Jupiter; and his wife Calpurnia thought that the pediment of their house fell, and that her husband was stabbed in her arms; and on a sudden the door of the room flew open of its own accord. Both for these reasons and because of poor health he hesitated for a long time whether to stay at home and put off what he had planned to do in the senate; but at last, urged by Decimus Brutus not to disappoint the full meeting which had for some time been waiting for him, he went forth almost at the end of the fifth hour; and when a note revealing the plot was handed him by someone on the way, he put it with others which he held in his left hand, intending to read them presently. Then, after several victims had been slain, and he could not get favorable omens, he entered the Senate in defiance of portents, laughing at Spurinna and calling him a false prophet, because the Ides of March were come without bringing him harm; though Spurinna replied that they had of a truth come, but they had not gone.

On these same events, Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “Fate, however, is to all appearance more unavoidable than unexpected. For many strange prodigies and apparitions are said to have been observed shortly before the event. As to the lights in the heavens, the noises heard in the night, and the wild birds which perched in the forum, these are not perhaps worth taking notice of in so great a case as this. Strabo, the philosopher, tells us that a number of men were seen, looking as if they were heated through with fire, contending with each other; that a quantity of flame issued from the hand of a soldier’s servant, so that they who saw it thought he must be burnt, but that after all he had no hurt. As Cæsar was sacrificing, the victim’s heart was missing, a very bad omen, because no living creature can subsist without a heart. One finds it also related by many, that a soothsayer bade him prepare for some great danger on the ides of March. When the day was come, Cæsar, as he went to the senate, met this soothsayer, and said to him by way of raillery, “The ides of March are come;” who answered him calmly, “Yes, they are come, but they are not past.” The day before this assassination, he supped with Marcus Lepidus; and as he was signing some letters, according to his custom, as he reclined at table, there arose a question what sort of death was the best. At which he immediately, before any one could speak, said, “A sudden one.” [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“After this, as he was in bed with his wife, all the doors and windows of the house flew open together; he was startled at the noise, and the light which broke into the room, and sat up in his bed, where by the moonshine he perceived Calpurnia fast asleep, but heard her utter in her dream some indistinct words and inarticulate groans. She fancied at that time she was weeping over Cæsar, and holding him butchered in her arms. Others say this was not her dream, but that she dreamed that a pinnacle which the senate, as Livy relates, had ordered to be raised on Cæsar’s house by way of ornament and grandeur, was tumbling down, which was the occasion of her tears and ejaculations. When it was day, she begged of Cæsar, if it were possible, not to stir out, but to adjourn the senate to another time; and if he slighted her dreams, that he would be pleased to consult his fate by sacrifices, and other kinds of divination. Nor was he himself without some suspicion and fears; for he never before discovered any womanish superstition in Calpurnia, whom he now saw in such great alarm. Upon the report which the priests made to him, that they had killed several sacrifices, and still found them inauspicious, he resolved to send Antony to dismiss the senate.

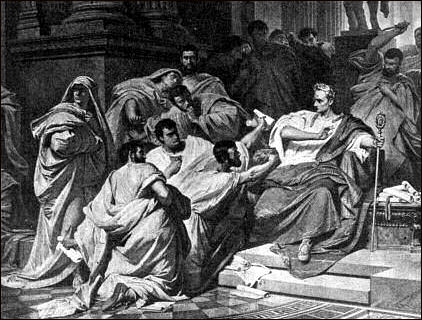

Details of the Assassination of Caesar

The assassination took place during a routine meeting. Caesar was late. He had been warned by his wife Calpurnia that he shouldn't go to the Senate that day. He had to be fetched from his house and arrived about 11:00am. Shortly after he entered the Senate he was approached by a Senator with a petition. He was then approached by the conspirators.

One Senator grabbed Caesar's robe at the neck, the signal to begin the attack, Another attempted to shove his dagger into Caesar's neck but only grazed him. Caesar tried to escape by twisting his body around but was then was struck by another dagger in the side and was seriously wounded by a dagger blow from Cassius to the face and one from Brutus the groin. Other dagger blows from other Senators finished him off.

Caesar died at the base of a statue of Pompey. His last words were: "Thou, too, Brutus, my son!" The autopsies showed he had been stabbed 23 times, including a fatal one to the chest. After the murder Caesar's onetime ally Marc Anthony, went to the Roman Forum "to bury Caesar, not to praise him." Brutus attempted to give a speech at the Forum and was shouted down and then was forced to barricade himself and other conspirators at the Capitol. After his death Caesar was named a god and a month was named after him.

Events Before the Assassination of Caesar

Plutarch wrote: “From this time they tried the inclinations of all their acquaintances that they durst trust, and communicated the secret to them, and took into the design not only their familiar friends, but as many as they believed bold and brave and despisers of death. For which reason they concealed the plot from Cicero, though he was very much trusted and as well beloved by them all, lest, to his own disposition, which was naturally timorous, adding now the weariness and caution of old age, by his weighing, as he would do, every particular, that he might not make one step without the greatest security, he should blunt the edge of their forwardness and resolution in a business which required all the despatch imaginable. As indeed there were also two others that were companions of Brutus, Statilius the Epicurean, and Favonius the admirer of Cato, whom he left out for this reason: as he was conversing one day with them, trying them at a distance, and proposing some such question to be disputed of as among philosophers, to see what opinion they were of, Favonius declared his judgment to be that a civil war was worse than the most illegal monarchy; and Statilius held, that to bring himself into troubles and danger upon the account of evil or foolish men did not become a man that had any wisdom or discretion. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), The Assassination of Julius Caesar, from Marcus Brutus, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

Plutarch wrote: “From this time they tried the inclinations of all their acquaintances that they durst trust, and communicated the secret to them, and took into the design not only their familiar friends, but as many as they believed bold and brave and despisers of death. For which reason they concealed the plot from Cicero, though he was very much trusted and as well beloved by them all, lest, to his own disposition, which was naturally timorous, adding now the weariness and caution of old age, by his weighing, as he would do, every particular, that he might not make one step without the greatest security, he should blunt the edge of their forwardness and resolution in a business which required all the despatch imaginable. As indeed there were also two others that were companions of Brutus, Statilius the Epicurean, and Favonius the admirer of Cato, whom he left out for this reason: as he was conversing one day with them, trying them at a distance, and proposing some such question to be disputed of as among philosophers, to see what opinion they were of, Favonius declared his judgment to be that a civil war was worse than the most illegal monarchy; and Statilius held, that to bring himself into troubles and danger upon the account of evil or foolish men did not become a man that had any wisdom or discretion. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), The Assassination of Julius Caesar, from Marcus Brutus, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“But Labeo, who was present, contradicted them both and Brutus, as if it had been an intricate dispute, and difficult to be decided, held his peace for that time, but afterwards discovered the whole design to Labeo, who readily undertook it. The next thing that was thought convenient was to gain the other Brutus surnamed Albinus, a man of himself of no great bravery or courage, but considerable for the number of gladiators that he was maintaining for a public show, and the great confidence that Caesar put in him. When Cassius and Labeo spoke with him concerning the matter, he gave them no answer; but, seeking an interview with Brutus himself alone, and finding that he was their captain, he readily consented to partake in the action. And among the others, also, the most and best were gained by the name of Brutus. And, though they neither gave nor took any oath of secrecy, nor used any other sacred rite to assure their fidelity to each other, yet all kept their design so close, were so wary, and held it so silently among themselves that, though by prophecies and apparitions and signs in the sacrifices the gods gave warning of it, yet could it not be believed.

Portia, wife of Brutus, a heroine in Shakespeare's play

“But a meeting of the senate being appointed, at which it was believed that Caesar would be present, they agreed to make use of that opportunity; for then they might appear all together without suspicion; and, besides, they hoped that all the noblest and leading men of the commonwealth, being then assembled as soon as the great deed was done, would immediately stand forward and assert the common liberty. The very place too where the senate was to meet seemed to be by divine appointment favourable to their purpose. It was a portico, one of those joining the theatre, with a large recess, in which there stood a statue of Pompey, erected to him by the commonwealth, when he adorned that part of the city with the porticos and the theatre. To this place it was that the senate was summoned for the middle of March (the Ides of March is the Roman name for the day); as if some more than human power were leading the man thither, there to meet his punishment for the death of Pompey.

“As soon as it was day, Brutus, taking with him a dagger, which none but his wife knew of, went out. The rest met together at Cassiuss house, and brought forth his son that was that day to put on the manly gown, as it is called, into the forum; and from thence, going all to Pompeys porch, stayed there, expecting Caesar to come without delay to the senate. Here it was chiefly that any one who had known what they had purposed, would have admired the unconcerned temper and the steady resolution of these men in their most dangerous undertaking; for many of them, being praetors, and called upon by their office to judge and determine causes, did not only hear calmly all that made application to them and pleaded against each other before them, as if they were free from all other thoughts, but decided causes with as much accuracy and judgment as they had heard them with attention and patience. And when one person refused to stand to the award of Brutus, and with great clamour and many attestations appealed to Caesar, Brutus, looking round about him upon those that were present, said, "Caesar does not hinder me, nor will he hinder me, from doing according to the laws."...

“For now news was brought that Caesar was coming, carried in a litter. For, being discouraged by the ill-omens that attended his sacrifice, he had determined to undertake no affairs of any great importance that day, but to defer them till another time, excusing himself that he was sick. As soon as he came out of his litter, Popilius Laenas, he who but a little before had wished Brutus good success in his undertaking, coming up to him, conversed a great while with him, Caesar standing still all the while, and seeming to be very attentive. The conspirators (to give them this name), not being able to hear what he said, but guessing by what themselves were conscious of that this conference was the discovery of their treason, were again disheartened, and, looking upon one another, agreed from each others countenances that they should not stay to be taken, but should all kill themselves. And now when Cassius and some others were laying hands upon their daggers under their robes, and were drawing them out, Brutus, viewing narrowly the looks and gesture of Laenas, and finding that he was earnestly petitioning and not accusing, said nothing, because there were many strangers to the conspiracy mingled amongst them: but by a cheerful countenance encouraged Cassius. And after a little while, Laenas, having kissed Caesars hand, went away, showing plainly that all his discourse was about some particular business relating to himself.”

Suetonius on the Assassination of Caesar

Suetonius wrote: ““As he took his seat, the conspirators gathered about him as if to pay their respects, and straightway Tillius Cimber, who had assumed the lead, came nearer as though to ask something; and when Caesar with a gesture put him off to another time, Cimber caught his toga by both shoulders; then as Caesar cried, "Why, this is violence!" one of the Cascas stabbed him from one side just below the throat. Caesar caught Casca's arm and ran it through with his stylus, but as he tried to leap to his feet, he was stopped by another wound. When he saw that he was beset on every side by drawn daggers, he muffled his head in his robe, and at the same time drew down its lap to his feet with his left hand, in order to fall more decently, with the lower part of his body also covered. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

“And in this wise he was stabbed with three and twenty wounds, uttering not a word, but merely a groan at the first stroke, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek, 'You too, my child?" All the conspirators made off, and he lay there lifeless for some time, until finally three common slaves put him on a litter and carried him home, with one arm hanging down. And of so many wounds none turned out to be mortal, in the opinion of the physician Antistius, except the second one in the breast. The conspirators had intended after slaying him to drag his body to the Tiber, confiscate his property, and revoke his decrees; but they forebore through fear of Marcus Antonius the consul, and Lepidus, the master of horse.

“Then at the request of his father-in-law, Lucius Piso, the will was unsealed and read in Antonius' house, which Caesar had made on the preceding Ides of September at his place near Lavicum [September 18, 45 B.C.], and put in the care of the chief of the Vestals. Quintus Tubero states that from his first consulship until the beginning of the civil war it was his wont to write down Gnaeus Pompeius as his heir, and to read this to the assembled soldiers. In his last will, however, he named three heirs, his sisters' grandsons — Gaius Octavius (to three-fourths of his estate), and Lucius Pinarius and Quintus Pedius (to share the remainder). At the end of the will, too, he adopted Gaius Octavius into his family and gave him his name. He named several of his assassins among the guardians of his son, in case one should be born to him, and Decimus Brutus even among his heirs in the second degree. To the people he left his gardens near the Tiber for their common use and three hundred sesterces to each man.

Plutarch on Caesar’s Assassination

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “The scene of this murder, in which the senate met that day, was the same in which Pompey’s statue stood, and was one of the edifices which Pompey had raised and dedicated with his theatre to the use of the public, plainly showing that there was something of a supernatural influence which guided the action, and ordered it to that particular place. Cassius, just before the act, is said to have looked towards Pompey’s statue, and silently implored his assistance, though he had been inclined to the doctrines of Epicurus. But this occasion and the instant danger, carried him away out of all his reasonings, and filled him for the time with a sort of inspiration. As for Antony, who was firm to Cæsar, and a strong man, Brutus Albinus kept him outside the house, and delayed him with a long conversation contrived on purpose. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“When Cæsar entered, the senate stood up to show their respect to him, and of Brutus’s confederates, some came about his chair and stood behind it, others met him, pretending to add their petitions to those of Tillius Cimber, in behalf of his brother, who was in exile; and they followed him with their joint supplications till he came to his seat. When he was sat down, he refused to comply with their requests, and upon their urging him further, began to reproach them severally for their importunities, when Tillius, laying hold of his robe with both his hands, pulled it down from his neck, which was the signal for the assault. Casca gave him the first cut, in the neck, which was not mortal nor dangerous, as coming from one who at the beginning of such a bold action was probably very much disturbed. Cæsar immediately turned about, and laid his hand upon the dagger and kept hold of it. And both of them at the same time cried out, he that received the blow, in Latin, “Vile Casca, what does this mean?” and he that gave it, in Greek, to his brother, “Brother, help!”

“Upon this first onset, those who were not privy to the design were astonished, and their horror and amazement at what they saw were so great, that they durst not fly nor assist Cæsar, nor so much as speak a word. But those who came prepared for the business inclosed him on every side, with their naked daggers in their hands. Which way soever he turned, he met with blows, and saw their swords levelled at his face and eyes, and was encompassed, like a wild beast in the toils, on every side. For it had been agreed they should each of them make a thrust at him, and flesh themselves with his blood; for which reason Brutus also gave him one stab in the groin. Some say that he fought and resisted all the rest, shifting his body to avoid the blows, and calling out for help, but that when he saw Brutus’s sword drawn, he covered his face with his robe and submitted, letting himself fall, whether it were by chance, or that he was pushed in that direction by his murderers, at the foot of the pedestal on which Pompey’s statue stood, and which was thus wetted with his blood. So that Pompey himself seemed to have presided, as it were, over the revenge done upon his adversary, who lay here at his feet, and breathed out his soul through his multitude of wounds, for they say he received three and twenty. And the conspirators themselves were many of them wounded by each other, whilst they all levelled their blows at the same person.”

In the account of the assassination from Brutus’s biography, Plutarch wrote: “Now when the senate was gone in before to the chamber where they were to sit, the rest of the company placed themselves close about Caesars chair, as if they had some suit to make to him, and Cassius, turning his face to Pompeys statue, is said to have invoked it, as if it had been sensible of his prayers. Trebonius, in the meanwhile, engaged Antonys attention at the door, and kept him in talk outside. When Caesar entered, the whole senate rose up to him. As soon as he was sat down, the men all crowded round about him, and set Tillius Cimber, one of their own number, to intercede in behalf of his brother that was banished; they all joined their prayers with his, and took Caesar by the hand, and kissed his head and his breast. But he putting aside at first their supplications, and afterwards, when he saw they would not desist, violently rising up, Tillius with both hands caught hold of his robe and pulled it off from his shoulders, and Casca, that stood behind him, drawing his dagger, gave him the first, but a slight wound, about the shoulder. Caesar snatching hold of the handle of the dagger, and crying out aloud in Latin, "Villain Casca, what do you?" he, calling in Greek to his brother, bade him come and help. And by this time, finding himself struck by a great many hands, and looking around about him to see if he could force his way out, when he saw Brutus with his dagger drawn against him, he let go Cascas hand, that he had hold of and covering his head with his robe, gave up his body to their blows. And they so eagerly pressed towards the body, and so many daggers were hacking together, that they cut one another; Brutus, particularly, received a wound in his hand, and all of them were besmeared with the blood. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), The Assassination of Julius Caesar, from Marcus Brutus, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

Place Where Julius Caesar was Stabbed Found

Caesar's tomb

In 2012, archaeologists with Spanish National Research Council announced that they had found the spot where it is believed that Julius Caesar was stabbed discovered: a concrete structure in the monumental complex of Torre Argentina in Rome. Stephanie Pappas wrote in Live Science: “Archaeologists have unearthed a concrete structure nearly 10 feet wide and 6.5 feet tall that may have been erected by Augustus, Julius Caesar's successor, to condemn the assassination. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, October 11, 2012 +++]

“The structure is at the base of the Curia, or Theater, of Pompey, the spot where classical writers reported the stabbing took place. "We always knew that Julius Caesar was killed in the Curia of Pompey on March 15th 44 B.C. because the classical texts pass on so, but so far no material evidence of this fact, so often depicted in historicist painting and cinema, had been recovered," Antonio Monterroso, a researcher at the Spanish National Research Council, said in a statement. +++

“Classical texts also say that years after the assassination, the Curia was closed and turned into a memorial chapel for Caesar. The researchers are studying this building along with another monument in the same complex, the Portico of the Hundred Columns, or Hecatostylon; they are looking for links between the archaeology of the assassination and what has been portrayed in art. "It is very attractive, in a civic and citizen sense, that thousands of people today take the bus and the tram right next to the place where Julius Caesar was stabbed 2,056 years ago," Monterroso said.” +++

Place Where Caesar Was Assassinated Opens as a Tourist Attraction

In June 2023, four temples at Rome;s Largo Argentina (Argentina Square), where Caesar masterminded his political strategies and was later fatally stabbed in 44 B.C., were made accessible. Associated Press reported: Four temples from ancient Rome, dating back as far as the 3rd century B.C. stand smack in the middle of one of the modern city's busiest crossroads. Until 2023, practically the only ones getting a close-up view of the temples were cats that prowled the so-called “Sacred Area,” on the edge of the site where Julius Caesar was assassinated. With the help of funding from Bulgari, the luxury jeweler, the grouping of temples can now be visited by the public. [Source: Frances D'emilio, Associated Press, June 20, 2023]

For decades, the curious had to gaze down from the bustling sidewalks rimming Largo Argentina to admire the temples below. That's because, over the centuries, the city had been built up, layer by layer, to levels several meters above the area used in Caesar’s time. Behind two of the temples is a foundation and part of a wall that archaeologists believe were part of Pompey's Curia, a large rectangular-shaped hall that temporarily hosted the Roman Senate when Caesar was murdered.

place Caesar was stabbed

What leads archaeologists to pinpoint the ruins as Pompey's Curia? “We know it with certainty because latrines were found on the sides" of Pompey's Curia, and ancient texts mentioned the latrines, said Claudio Parisi Presicce, an archaeologist and Rome's top official for cultural heritage. The temples emerged during the demolition of medieval-era buildings in the late 1920s, part of dictator Benito Mussolini’s campaign to remake the urban landscape. A tower at one edge of Largo Argentina once topped a medieval palace.

The temples are designated A, B, C and D, and are believed to have been dedicated to female deities. One of the temples, reached by an imposing staircase and featuring a circular form and with six surviving columns, is believed to have been erected in honor of Fortuna, a goddess of chance associated with fertility. Taken together, the temples make for "one of the best-preserved remains of the Roman Republic,'' Parisi Presicce.

Also visible are the travertine paving stones that Emperor Domitian had laid down after a fire in 80 A.D. ravaged a large swath of Rome, including the Sacred Area. On display are some of the artifacts found during last century's excavation. Among them is a stone colossal head of one of the deities honored in the temples, chinless and without its lower lip. Another is a stone fragment of a winged angel of victory.

Over the last decades, a cat colony flourished among the ruins. Felines lounged undisturbed, and cat lovers were allowed to feed them. On Monday, one black-and-white cat sprawled lazily on its back atop the stone stump of what was once a glorious column. Bulgari helped pay for the construction of the walkways and nighttime illumination. A relief to tourists who step gingerly over the uneven ancient paving stones of the Roman Forum. The Sacred Area's wooden walkways are wheelchair and baby-stroller-friendly. For those who can't handle the stairs down from the sidewalk, an elevator platform is available. The attraction is open every day except for Mondays and some major holidays, with general admission tickets priced at 5 euros ($5.50).

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except last picture Live Science

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024