Home | Category: Age of Caesar

JULIUS CAESAR IN GAUL

Gaul at the time of Caesar's arrival in 59 BC

In 59 B.C., after serving a year as consul, Caesar had himself named the governor of Gaul, where he distinguished himself as a superb organizer and a motivator of soldiers with whom he worked with, fought with and suffered with. He inspired such respect and affection from the men who served under him it was said they would do anything for him. Caesar personally selected Gaul for his province to govern. At that time the most forbidding part of the Roman territory. It was the home of barbarians, with no wealth like that of Asia, and few relics of a former civilization like those of Spain and Africa.

Caesar governed Gaul from 58 to 49 B.C. David Silverman of Reed College wrote: Caesar “chose for his province Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum, but the Senate added to this Transalpine Gaul, which as it turned out was where Caesar would spend most of his time, returning to the Italian side of the Alps periodically to meet with his people from the city and to keep his finger on what was happening on the domestic scene.” [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

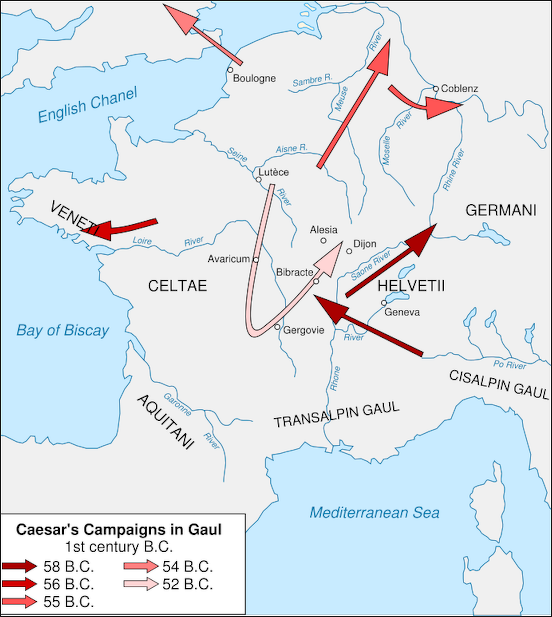

Suetonius wrote: “During the nine years of his command this is in substance what he did. All that part of Gallia which is bounded by the Pyrenees, the Alps and the Cévennes, and by the Rhine and Rhone rivers, a circuit of some 3,200 miles [Roman measure, about 3,106 English miles], with the exception of some allied states which had rendered him good service, he reduced to the form of a province; and imposed upon it a yearly tribute of 40,000,000 sesterces. He was the first Roman to build a bridge and attack the Germans beyond the Rhine; and he inflicted heavy losses upon them. He invaded the Britons too, a people unknown before, vanquished them, and exacted moneys and hostages. Amid all these successes he met with adverse fortune but three times in all: in Britannia, where his fleet narrowly escaped destruction in a violent storm; in Gallia, when one of his legions was routed at Gergovia; and on the borders of Germania, when his lieutenants Titurius and Aurunculeius were ambushed and slain. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Greatest Victory: The Battle of Alesia, Gaul 52 BC” by John Sadler, Rosie Serdiville (2016) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Legion: The Epic Saga of Julius Caesar's Elite Tenth Legion and the Armies of Rome” by Stephen Dando-Collins (2002) Amazon.com

“Caesar's Army: the Evolution, Composition, Tactics, Equipment & Battles of the Roman Army” by Harry Pratt Judson (2011) Amazon.com;

“Caesar's Great Success: Sustaining the Roman Army on Campaign” by Alexander Merrow , Agostino von Hassell, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Caesar, Life of a Colossus” by Adrian Goldsworthy (2006) Amazon.com

“Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar” by Tom Holland (2015) Amazon.com

“The Lives of the Caesars” (A Penguin Classics Hardcover) by Suetonius, Tom Holland Amazon.com;

“Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic” by Tom Holland (2003) Amazon.com

“The Landmark Julius Caesar: The Complete Works : Gallic War, Civil War, Alexandrian War, African War, and Spanish War : in One Volume, with Maps, Annotations, Appendices, and Encyclopedic Index” by 2017) Amazon.com

Why Did Caesar Choose to Go to Gaul

It is not easy for us to say exactly what was in the mind of Caesar when he selected Gaul for his province. But there were three or four things, no doubt, that Caesar saw clearly. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

In the first place, he saw that the power which should hereafter rule the Roman state must be a military power. Sulla had succeeded by the help of his army, and Pompey had failed by giving up his army. If he himself should ever establish his own power, it must be by the aid of a strong military force. In the next place, he saw that no other province afforded the same political opportunities as those which Gaul presented. It is true that the distant province of Syria might open a way for the conquest of Parthia, and for attaining the glories of another Alexander. But Syria was too far removed from Roman politics; and Caesar’s first ambition was political power, and not military glory. \~\

area in pink conqured by Caesar by 51 BC

Caesar saw that the conquest of Gaul was necessary for the protection of the Roman state. The invasions of the northern barbarians—the Gauls, the Cimbri and the Teutones had twice already threatened Rome with destruction. By its conquest Gaul might be made a barrier against barbarism.Moreover, he saw that Rome was in need of new and fertile lands for colonization. Italy was overcrowded. The most patriotic men had seen the need of extra-Italian colonies. Gaius Gracchus had sought an outlet in Africa. He himself had advocated settlements in the valley of the Po. What Italy needed most, after a stable government, was an outlet for her surplus population. His own ambition and the highest interests of his country Caesar believed to be at one. By conquering Gaul he would be fighting not for Pompey or the senate, but for himself and Rome. \~\

The Roman historian Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) wrote: “Backed therefore by his father-in-law and son-in-law, out of all the numerous provinces he made Gallia his choice, as the most likely to enrich him and furnish suitable material for triumphs. At first, it is true, by the bill of Vatinius he received only Gallia Cisalpina with the addition of Illyricum; but presently he was assigned Gallia Comata as well by the senate, since the members feared that even if they should refuse it, the people would give him this also. Transported with joy at this success, he could not keep from boasting a few days later before a crowded house, that having gained his heart's desire to the grief and lamentation of his opponents, he would therefore from that time mount on their heads [used in a double sense, one sexual]; and when someone insultingly remarked that that would be no easy matter for any woman, he replied in the same vein that Semiramis too had been queen in Syria and the Amazons in days of old had held sway over a great part of Asia.

“When at the close of his consulship the praetors Gaius Memmius and Lucius Domitius moved an inquiry into his conduct during the previous year, Caesar laid the matter before the senate; and when they failed to take it up, and three days had been wasted in fruitless wrangling, went off to his province. Whereupon his quaestor was at once arraigned on several counts, as a preliminary to his own impeachment. Presently he himself too was prosecuted by Lucius Antistius, tribune of the commons, and it was only by appealing to the whole college that he contrived not to be brought to trial, on the ground that he was absent on public service. Then to secure himself for the future, he took great pains always to put the magistrates for the year under personal obligation, and not to aid any candidates or suffer any to be elected, save such as guaranteed to defend him in his absence. And he did not hesitate in some cases to exact an oath to keep this pledge or even a written contract.

“[55 B.C.] When, however, Lucius Domitius, candidate for the consulship, openly threatened to effect as consul what he had been unable to do as praetor, and to take his armies from him, Caesar compelled Pompeius and Crassus to come to Luca, a city in his province, where he prevailed on them to stand for a second consulship, to defeat Domitius; and he also succeeded through their influence in having his term as governor of Gallia made five years longer. Encouraged by this, he added to the legions which he had received from the state others at his own cost, one actually composed of men of Gallia Transalpina and bearing a Gallic name too (for it was called Alauda [A Celtic word meaning a crested lark (Plin. N.H. 11.37) which was the device on the helmets of the legion]), which he trained in the Roman tactics and equipped with Roman arms; and later on he gave every man of it citizenship. After that he did not let slip any pretext for war, however unjust and dangerous it might be, picking quarrels as well with allied, as with hostile and barbarous nations; so that once the senate decreed that a commission be sent to inquire into the condition of the Gallic provinces, and some even recommended that Caesar be handed over to the enemy. But as his enterprises prospered, thanksgivings were appointed in his honor oftener and for longer periods than for anyone before his time.

Gaul at the Time Caesar Arrived

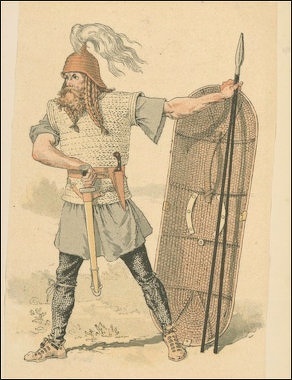

the locals in Gaul

Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.) wrote in “The Gallic Wars” (“De Bello Gallico” c. 51 B.C.): “When Caesar arrived in Gaul the leaders of one party were the Aedui, of the other the Sequani. The latter, being by themselves inferior in strength — since the highest authority from ancient times rested with the Aedui, and their dependencies were extensive — had made Ariovistus and the Germans their friends, and with great sacrifices and promises had brought them to their side. Then, by several successful engagements and the slaughter of all the Aeduan nobility, they had so far established their predominance as to transfer a great part of the dependents from the Aedui to themselves, receiving from them as hostages the children of their chief men, compelling them as a state to swear that they would entertain no design against the Sequani, occupying a part of the neighbouring territory which they had seized by force, and securing the chieftaincy of all Gaul. This was the necessity which had compelled Diviciacus to set forth on a journey to the Senate at Rome for the purpose of seeking aid; but he had returned without achieving the object. [Source: Gallic War by Julius Caesar, Book VI (chapters 11 20). Loeb Classical Library, 1917, Bill Thayer, penelope.uchicago.edu]

“By the arrival of Caesar a change of affairs was brought about. Their hosts were restored to the Aedui, their old dependencies restored, and new ones secured through Caesar's efforts (as those who had joined in friendly relations with them found that they enjoyed a better condition and a fairer rule), and their influence and position were increased in all other respects: in result whereof the Sequani had lost the chieftaincy. To their place the Remi had succeeded; and as it was perceived that they had equal influence with Caesar, the tribes which, by reason of ancient animosities, could in no wise join the Aedui were delivering themselves as dependents to the Remi. These tribes the Remi carefully protected, and by this means they sought to maintain their new and suddenly acquired authority. The state of things then at the time in question was that the Aedui were regarded as by far the chief state, while the Remi held the second place in importance.

“Throughout Gaul there are two classes of persons of definite account and dignity. As for the common folk, they are treated almost as slaves, venturing naught of themselves, never taken into counsel. The more part of them, oppressed as they are either by debt, or by the heavy weight of tribute, or by the wrongdoing of the more powerful men, commit themselves in slavery to the nobles, who have, in fact, the same rights over them as masters over slaves. Of the two classes above mentioned one consists of Druids, the other of knights. The former are concerned with divine worship, the due performance of sacrifices, public and private, and the interpretation of ritual questions: a great number of young men gather about them for the sake of instruction and hold them in great honour. In fact, it is they who decide in almost all disputes, public and private; and if any crime has been committed, or murder done, or there is any disposes about succession or boundaries, they also decide it, determining rewards and penalties: if any person or people does not abide by their decision, they ban such from sacrifice, which is their heaviest penalty. Those that are so banned are reckoned as impious and criminal; all men move out of their path and shun their approach and conversation, for fear they may get some harm from their contact, and no justice is done if they seek it, no distinction falls to their share. Of all these Druids one is chief, who has the highest authority among them. At his death, either any other that is preëminent in position succeeds, or, if there be several of equal standing, they strive for the primacy by the vote of the Druids, or sometimes even with armed force. These Druids, at a certain time of the year, meet within the borders of the Carnutes, whose territory is reckoned as the centre of all Gaul, and sit in conclave in a consecrated spot. Thither assemble from every side all that have disputes, and they obey the decisions and judgments of the Druids. It is believed that their rule of life was discovered in Britain and transferred thence to Gaul; and to day those who would study the subject more accurately journey, as a rule, to Britain to learn it.

“The Druids usually hold aloof from war, and do not pay war taxes with the rest; they are excused from military service and exempt from all liabilities. Tempted by these great rewards, many young men assemble of their own motion to receive their training; many are sent by parents and relatives. Report says that in the schools of the Druids they learn by heart a great number of verses, and therefore some persons remain twenty years under training. And they do not think it proper to commit these utterances to writing, although in almost all other matters, and in their public and private accounts, they make use of Greek letters. I believe that they have adopted the practice for two reasons — that they do not wish the rule to become common property, nor those who learn the rule to rely on writing and so neglect the cultivation of the memory; and, in fact, it does usually happen that the assistance of writing tends to relax the diligence of the student and the action of the memory. The cardinal doctrine which they seek to teach is that souls do not die, but after death pass from one to another; and this belief, as the fear of death is thereby cast aside, they hold to be the greatest incentive to valour. Besides this, they have many discussions as touching the stars and their movement, the size of the universe and of the earth, the order of nature, the strength and the powers of the immortal gods, and hand down their lore to the young men.

“The other class are the knights. These, when there is occasion, upon the incidence of a war — and before Caesar's coming this would happen well-nigh every year, in the sense that they would either be making wanton attacks themselves or repelling such — are all engaged therein; and according to the importance of each of them in birth and resources, so is the number of liegemen and dependents that he has about him. This is the one form of influence and power known to them.”

Julius Caesar on the Gauls and Their Customs and Religion

Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.) wrote in “The Gallic Wars” (“De Bello Gallico” c. 51 B.C.): “The Gallic people, in general, are remarkably addicted to religious observances; and for this reason persons suffering from serious maladies c s. and those whose lives are passed in battle and danger offer or vow to offer human sacrifices, and employ Druids to perform the sacrificial rites; for they believe that unless for man's life the life of man be duly offered, the divine spirit cannot be propitiated. They also hold regular state sacrifices of the same kind. They have, besides, colossal images, the limbs of which, made of wicker work, they fill with living men and set on fire; and the victims perish, encompassed by the flames. [Source: Internet Archive. Princeton]

“They regard it as more acceptable to the gods to punish those who are caught in the commission of theft, robbery, or any other crime; but, in default of criminals, they actually resort to the sacrifice of the innocent. The god whom they most reverence is Mercury, whose images abound. He is regarded as the inventor of all arts and the pioneer and guide of travellers; and he is believed to be all-powerful in promoting commerce and the acquisition of wealth. Next to him they reverence Apollo, Mars, Jupiter, and Minerva. Their notions about these deities are much the same as those of other peoples: Apollo they regard as the dispeller of disease, Minerva as the originator of industries and handicrafts, Jupiter as the suzerain of the celestials, and Mars as the lord of war. To Mars, when they have resolved upon battle, they commonly dedicate the spoils: after victory they sacrifice the captured cattle, and collect the rest of the booty in one spot. In the territories of many tribes are to be seen heaps of such spoils reared on consecrated ground; and it has rarely happened that any one dared, despite religion, either to conceal what he had captured or to remove what had been consecrated. For such an offense the law prescribes the heaviest punishment with torture

“The Gauls universally describe themselves as descendants of Dis Pater,2 affirming that this is the Druidical tradition. For this reason they measure all periods of time not by days but by nights, and reckon birthdays, the first of the month, and the first of the year on the principle that day comes after night. As regards the other customs of daily life, about the only point ispecul,ar in which they differ from the rest of mankind is this, they do not allow their children to come near them openly 1 until they are old enough for military service; and they regard it as unbecoming for a son, while he is still a boy, to appear in public where his father can see him.

“It is the custom for married men to take from their own property an amount equivalent, according to valuation, to the sum which they have received from their wives as dowry, and lump the two together. The whole property is jointly administered and the interest saved; and the joint shares of husband and wife, with the interest of past years, go to the survivor. Husbands have power of life and death over Status of their wives as well as their children: on the death of the head of a family of high birth, his relations assemble, and, if his death gives rise to suspicion, examine his wives under torture like slaves, and, if their guilt is proved, bum t em to death with all kinds of tortures I funerals, considering the Gallic standard of living are splendid and costly: everything, even including animals, which the departed are supposed to have cared for when they were alive, is consigned to the flames; and shortly before our time slaves and retainers who were known to have been beloved by their masters were burned along with them after the conclusion of the regular obsequies.

“The tribes which are regarded as comparatively well governed have a legal enactment to the effect that if any one hears any political rumour or intelligence from the neighbouring peoples, he is to inform the magistrate and not communicate it to any one else, as experience has proved that headstrong persons, who know nothing of affairs, are often alarmed by false reports and impelled to commit crimes and embark on momentous enterprises The magistrates suppress what appears to demand secrecy, and publish what they deem it expedient for the people to know. The discussion of politics, except in a formal assembly, is forbidden.”

Caesar as a Military Leader in Gaul

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”:“Thus far have we followed Caesar's actions before the wars of Gaul. After this, he seems to begin his course afresh, and to enter upon a new life and scene of action. And the period of those wars which he now fought, and those many expeditions in which he subdued Gaul, showed him to be a soldier and general not in the least inferior to any of the greatest and most admired commanders who had ever appeared at the head of armies. For if we compare him with the Fab, the Metelli, the Scipios, and with those who were his contemporaries, or not long before him, Sylla, Marius, the Luculli, or even Pompey himself, whose glory, it may be said, went up at that time to heaven for every excellence in war, we shall find Caesar's actions to have surpassed them all. One he may be held to have outdone in consideration of the difficulty of the country in which he fought, another in the extent of territory which he conquered; some, in the number and strength of the enemy whom he defeated; one man, because of the wildness and perfidiousness of the tribes whose good-will he conciliated, another in his humanity and clemency to those he overpowered; others, again, in his gifts and kindnesses to his soldiers; all alike in the number of the battles which he fought and the enemies whom he killed. For he had not pursued the wars in Gaul full ten years when he had taken by storm above eight hundred towns, subdued three hundred states, and of the three millions of men, who made up the gross sum of those with whom at several times he engaged, he had killed one million and taken captive a second. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“He was so much master of the good-will and hearty service of his soldiers that those who in other expeditions were but ordinary men displayed a courage past defeating or withstanding when they went upon any danger where Caesar's glory was concerned. Such a one was Acilius, who, in the sea-fight before Marseilles, had his right hand struck off with a sword, yet did not quit his buckler out of his left, but struck the enemies in the face with it, till he drove them off and made himself master of the vessel. Such another was Cassius Scaeva, who, in a battle near Dyrrhachium, had one of his eyes shot out with an arrow, his shoulder pierced with one javelin, and his thigh with another; and having received one hundred and thirty darts upon his target, called to the enemy, as though he would surrender himself. But when two of them came up to him, he cut off the shoulder of one with a sword, and by a blow over the face forced the other to retire, and so with the assistance of his friends, who now came up, made his escape. Again, in Britain, when some of the foremost officers had accidentally got into a morass full of water, and there were assaulted by the enemy, a common soldier, whilst Caesar stood and looked on, threw himself in the midst of them, and after many signal demonstrations of his valour, rescued the officers and beat off the barbarians. He himself, in the end, took to the water, and with much difficulty, partly by swimming, partly by wading, passed it, but in the passage lost his shield. Caesar and his officers saw it and admired, and went to meet him with joy and acclamation. But the soldier, much dejected and in tears, threw himself down at Caesar's feet and begged his pardon for having let go his buckler. Another time in Africa, Scipio having taken a ship of Caesar's in which Granius Petro, lately appointed quaestor, was sailing, gave the other passengers as free prize to his soldiers, but thought fit to offer the quaestor his life. But he said it was not usual for Caesar's soldiers to take but give mercy, and having said so, fell upon his sword and killed himself.

“This love of honour and passion for distinction were inspired into them and cherished in them by Caesar himself, who, by his unsparing distribution of money and honours, showed them that he did not heap up wealth from the wars for his own luxury, or the gratifying his private pleasures, but that all he received was but a public fund laid by the reward and encouragement of valour, and that he looked upon all he gave to deserving soldiers as so much increase to his own riches. Added to this also, there was no danger to which he did not willingly expose himself, no labour from which he pleaded an exemption. His contempt of danger was not so much wondered at by his soldiers because they knew how much he coveted honour. But his enduring so much hardship, which he did to all appearance beyond his natural strength, very much astonished them. For he was a spare man, had a soft and white skin, was distempered in the head and subject to an epilepsy, which, it is said, first seized him at Corduba. But he did not make the weakness of his constitution a pretext for his ease, but rather used war as the best physic against his indispositions; whilst, by indefatigable journeys, coarse diet, frequent lodging in the field, and continual laborious exercise, he struggled with his diseases and fortified his body against all attacks. He slept generally in his chariots or litters, employing even his rest in pursuit of action. In the day he was thus carried to the forts, garrisons, and camps, one servant sitting with him, who used to write down what he dictated as he went, and a soldier attending behind him with his sword drawn.

“He drove so rapidly that when he first left Rome he arrived at the river Rhone within eight days. He had been an expert rider from his childhood; for it was usual with him to sit with his hands joined together behind his back, and so to put his horse to its full speed. And in this war he disciplined himself so far as to be able to dictate letters from on horseback, and to give directions to two who took notes at the same time or, as Oppius says, to more. And it is thought that he was the first who contrived means for communicating with friends by cipher, when either press of business, or the large extent of the city, left him no time for a personal conference about matters that required despatch. How little nice he was in his diet may be seen in the following instance. When at the table of Valerius Leo, who entertained him at supper at Milan, a dish of asparagus was put before him on which his host instead of oil had poured sweet ointment, Caesar partook of it without any disgust, and reprimanded his friends for finding fault with it. "For it was enough," said he, "not to eat what you did not like; but he who reflects on another man's want of breeding, shows he wants it as much himself." Another time upon the road he was driven by a storm into a poor man's cottage, where he found but one room, and that such as would afford but a mean reception to a single person, and therefore told his companions places of honour should be given up to the greater men, and necessary accommodations to the weaker, and accordingly ordered that Oppius, who was in bad health, should lodge within, whilst he and the rest slept under a shed at the door.”

Caesar’s Military Achievements in Gaul

Perhaps Caesar's greatest military achievement was his conquest and pacification of Gaul in which 55,000 Romans battled 250,000 Celts in a campaign that lasted from 58 to 51 B.C. His account of the events — Commentaries on the Gallic War — is still regarded as a masterpiece. Modern historians have compared it to Churchill's work. The historian Ernst Badian told National Geographic, "Blood was the characteristic of Alexander's whole campaign. There is nothing comparable in ancient history except Caesar in Gaul."

To protect his army of 40,000 men from the Gauls Caesar erected a fortress with a circumference of 14 miles. The fort was protected by hidden pit with upward pointing sticks, logs spiked with iron hooks, walls fashioned from forked timbers and double ditches. During one attack Celts hurled themselves bravely and foolishly at the fortress and were routed after the Roman cavalry charged down from a hill at a strategic time.

During his years in Gaul Caesar inexorably expanded Roman territory by defeating one tribe after another. He crossed the Rhine in 55 B.C. to preempt a German invasion. In 52 B.C., he put down the last great Gallic-Celtic uprising. Vercingetorix, the leader of the Gallic-Celtic forces, surrendered himself at the feet of Caesar who sent him to Rome where the Gallic leader was imprisoned for six years and then paraded through the streets and strangled in the Forum.

The provinces over which Caesar was placed at first included Cisalpine Gaul, that is, the valley of the Po; Illyricum, that is, the strip of territory across the Adriatic Sea; and Narbonensis, that is, a small part of Transalpine Gaul lying about the mouth of the Rhone. Within eight years he brought under his power all the territory bounded by the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Rhine, and the Atlantic Ocean, or about what corresponds to the modern countries of France, Belgium, and Holland. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

He at first conquered the Helvetii, a tribe lying on the outskirts of his own province of Narbonensis. He then met and drove back a great invasion of Germans, who, under a prince called Ariovistus, had crossed the Rhine, and threatened to overrun the whole of Gaul. He then pushed into the northern parts of Gaul, and conquered the Nervii and the neighboring tribes. He overcame the Veneti on the Atlantic coast, and conquered Aquitania. He also made two invasions into Britain (55, 54 B.C.), crossed the Rhine into Germany, and revealed to the Roman soldiers countries they had never seen before. After once subduing the various tribes of Gaul, he was finally caned upon to suppress a general insurrection, led by a powerful leader called Vercingetorix.

Caesar’s Early Victories and Conquests in Gaul

Caesar first conquered the Helvetii, a tribe lying on the outskirts of his own province of Narbonensis. He then met and drove back a great invasion of Germans, who, under a prince called Ariovistus, had crossed the Rhine, and threatened to overrun the whole of Gaul. David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “His tenure in Gaul began with a crisis, the westward movement of the Celto-Germanic Helvetii into the territory of Aedui, one of the Gallic tribes most friendly to Rome. Caesar's repulsion of the Helvetian migration induced the Gauls to look to him for help against Ariovistus, chief of the German Suebi, who likewise was looking to expand westward. The defeat of the Suebi at the Rhine confirmed Caesar's standing among the Gauls, but also convinced him that Roman rule ought to be extended throughout the whole of Gaul. In part his motivation was personal; as we have seen, in this period the path to personal power led more and more through the conquest of foreign enemies and the consequent accumulation of legions rather than through the Senate or the courts. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “His first war in Gaul was against the Helvetians and Tigurini, who having burnt their own towns, twelve in number, and four hundred villages, would have marched forward through that part of Gaul which was included in the Roman province, as the Cimbrians and Teutons formerly had done. Nor were they inferior to these in courage; and in numbers they were equal, being in all three hundred thousand, of which one hundred and ninety thousand were fighting men. Caesar did not engage the Tigurini in person, but Labienus, under his directions, routed them near the rivet Arar. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“The Helvetians surprised Caesar, and unexpectedly set upon him as he was conducting his army to a confederate town. He succeeded, however, in making his retreat into a strong position, where, when he had mustered and marshalled his men, his horse was brought to him; upon which he said, "When I have won the battle, I will use my horse for the chase, but at present let us go against the enemy," and accordingly charged them on foot. After a long and severe combat, he drove the main army out of the field, but found the hardest work at their carriages and ramparts, where not only the men stood and fought, but the women also and children defended themselves till they were cut to pieces; insomuch that the fight was scarcely ended till midnight. This action, glorious in itself, Caesar crowned with another yet more noble, by gathering in a body all the barbarians that had escaped out of the battle, above one hundred thousand in number, and obliging them to re-occupy the country which they had deserted and the cities which they had burnt. This he did for fear the Germans should pass it and possess themselves of the land whilst it lay uninhabited.”

Caesar Brings Gaul Under Control

After this Caesar pushed into the northern parts of Gaul, and conquered the Nervii and the neighboring tribes. He overcame the Veneti on the Atlantic coast, and conquered Aquitania. He also made two invasions into Britain (55, 54 B.C.), crossed the Rhine into Germany, and revealed to the Roman soldiers countries they had never seen before. After once subduing the various tribes of Gaul, he was finally caned upon to suppress a general insurrection, led by a powerful leader called Vercingetorix. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) \~]

Caesar and Ariovistus meet before battle

David Silverman wrote: “Resistance was stiffest in Northern Gaul, where Caesar with some difficulty subdued the Belgae and Nervii in 57 B.C. ; meanwhile, the Gauls of the Atlantic coast came along quietly, although in 56 B.C. an insurrection under the leadership of the Veneti had to be met in un-Roman fashion with a naval campaign. In 55 B.C. and 54 B.C. Gaul remained quiet, while Caesar explore the possibilities for the conquest of Germany (quickly abandoned) and Britain. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Ariovistus was a leader of the Suebi and other allied Germanic peoples while Caesar was in northern Gaul. Ariovistus and his followers took part in a war in Gaul, assisting the Arverni and Sequani in defeating their rivals, the Aedui. They then settled in large numbers into conquered Gallic territory, in the Alsace region. They were defeated in the Battle of Vosges and driven back over the Rhine in 58 B.C. by Julius Caesar. [Source: Wikipedia]

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “His second war was in defence of the Gauls against the Germans, though some time before he had made Ariovistus, their king, recognized at Rome as an ally. But they were very insufferable neighbours to those under his government; and it was probable, when occasion offered, they would renounce the present arrangements, and march on to occupy Gaul. But finding his officers timorous, and especially those of the young nobility who came along with him in hopes of turning their campaigns with him into a means for their own pleasure or profit, he called them together, and advised them to march off, and not run the hazard of a battle against their inclinations, since they had such weak unmanly feelings; telling them that he would take only the tenth legion and march against the barbarians, whom he did not expect to find an enemy more formidable than the Cimbri, nor, he added, should they find him a general inferior to Marius. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“Upon this, the tenth legion deputed some of their body to pay him their acknowledgments and thanks, and the other legions blamed their officers, and all, with great vigour and zeal, followed him many days' journey, till they encamped within two hundred furlongs of the enemy. Ariovistus's courage to some extent was cooled upon their very approach; for never expecting the Romans would attack the Germans, whom he had thought it more likely they would not venture to withstand even in defence of their own subjects, he was the more surprised at conduct, and saw his army to be in consternation. They were still more discouraged by the prophecies of their holy women, who foretell the future by observing the eddies of rivers, and taking signs from the windings and noise of streams, and who now warned them not to engage before the next new moon appeared. Caesar having had intimation of this, and seeing the Germans lie still, thought it expedient to attack them whilst they were under these apprehensions, rather than sit still and wait their time. Accordingly he made his approaches to the strongholds and hills on which they lay encamped, and so galled and fretted them that at last they came down with great fury to engage. But he gained a signal victory, and pursued them for four hundred furlongs, as far as the Rhine; all which space was covered with spoils and bodies of the slain. Ariovistus made shift to pass the Rhine with the small remains of an army, for it is said the number of the slain amounted to eighty thousand.”

Caesar Connections to Rome While He Was in Gaul

Caesar returned to Rome or the Italian side of the Po River periodically to meet with his allies and keep his finger on what was happening there. Suetonius wrote: “Within this same space of time he lost first his mother, then his daughter, and soon afterwards his grandchild. Meanwhile, as the community was aghast at the murder of Publius Clodius, the senate had voted that only one consul should be chosen, and expressly named Gnaeus Pompeius. When the tribunes planned to make him Pompeius' colleague, Caesar urged them rather to propose to the people that he be permitted to stand for a second consulship without coming to Rome, when the term of his governorship drew near its end, to prevent his being forced for the sake of the office to leave his province prematurely and without finishing the war. On the granting of this, aiming still higher and flushed with hope, he neglected nothing in the way of lavish expenditure or of favors to anyone, either in his public capacity or privately. He began a forum with the proceeds of his spoils, the ground for which cost more than a hundred million sesterces. He announced a combat of gladiators and a feast for the people in memory of his daughter, a thing quite without precedent. To raise the expectation of these events to the highest possible pitch, he had the material for the banquet prepared in part by his own household, although he had let contracts to the markets as well. He gave orders too that whenever famous gladiators fought without winning the favor of the people [when ordinarily they would be put to death], they should be rescued by force and kept for him. He had the novices trained, not in a gladiatorial school by professionals, but in private houses by Roman knights and even by senators who were skilled in arms, earnestly beseeching them, as is shown by his own letters, to give the recruits individual attention and personally direct their exercises. He doubled the pay of the legions for all time. Whenever grain was plentiful, he distributed it to them without stint or measure, and now and then gave each man a slave from among the captives. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.): “De Vita Caesarum, Divus Iulius” (“The Lives of the Caesars, The Deified Julius”), written A.D. c. 110, Suetonius, 2 vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, and London: William Henemann, 1920), Vol. I, pp. 3-119]

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: After his defeat of Ariovistus, “Caesar left his army at their winter quarters in the country of the Sequani, and, in order to attend to affairs at Rome, went into that part of Gaul which lies on the Po, and was part of his province; for the river Rubicon divides Gaul, which is on this side the Alps, from the rest of Italy. There he sat down and employed himself in courting people's favour; great numbers coming to him continually, and always finding their requests answered; for he never failed to dismiss all with present pledges of his kindness in hand, and further hopes for the future. And during all this time of the war in Gaul, Pompey never observed how Caesar was on the one hand using the arms of Rome to effect his conquests, and on the other was gaining over and securing to himself the favour of the Romans with the wealth which those conquests obtained him.” [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

Caesar Goes Back and Forth to Rome While Fighting in Gaul

Plutarch wrote in “Lives”: “But when he heard that the Belgae, who were the most powerful of all the Gauls, and inhabited a third part of the country, were revolted, and had got together a great many thousand men in arms, he immediately set out and took his way hither with great expedition, and falling upon the enemy as they were ravaging the Gauls, his allies, he soon defeated and put to flight the largest and least scattered division of them. For though their numbers were great, yet they made but a slender defence, and the marshes and deep rivers were made passable to the Roman foot by the vast quantity of dead bodies. Of those who revolted, all the tribes that lived near the ocean came over without fighting, and he, therefore, led his army against the Nerv, the fiercest and most warlike people of all in those parts. These live in a country covered with continuous woods, and having lodged their children and property out of the way in the depth of the forest, fell upon Caesar with a body of sixty thousand men, before he was prepared for them, while he was making his encampment. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46-c.120), Life of Caesar (100-44 B.C.), written A.D. 75, translated by John Dryden, MIT]

“They soon routed his cavalry, and having surrounded the twelfth and seventh legions, killed all the officers, and had not Caesar himself snatched up a buckler and forced his way through his own men to come up to the barbarians, or had not the tenth legion, when they saw him in danger, run in from the tops of the hills, where they lay, and broken through the enemy's ranks to rescue him, in all probability not a Roman would have been saved. But now, under the influence of Caesar's bold example, they fought a battle, as the phrase is, of more than human courage, and yet with their utmost efforts they were not able to drive the enemy out of the field, but cut them down fighting in their defence. For out of sixty thousand men, it is stated that not above five hundred survived the battle, and of four hundred of their senators not above three.

Caesar coins

“When the Roman senate had received news of this, they voted sacrifices and festivals to the gods, to be strictly observed for the space of fifteen days, a longer space than ever was observed for any victory before. The danger to which they had been exposed by the joint outbreak of such a number of nations was felt to have been great; and the people's fondness for Caesar gave additional lustre to successes achieved by him. He now, after settling everything in Gaul, came back again, and spent the winter by the Po, in order to carry on the designs he had in hand at Rome. All who were candidates for offices used his assistance, and were supplied with money from him to corrupt the people and buy their votes, in return of which, when they were chosen, they did all things to advance his power.

“But what was more considerable, the most eminent and powerful men in Rome in great numbers came to visit him at Lucca, Pompey, and Crassus, and Appius, the governor of Sardinia, and Nepos, the pro-consul of Spain, so that there were in the place at one time one hundred and twenty lictors and more than two hundred senators. In deliberation here held, it was determined that Pompey and Crassus should be consuls again for the following year; that Caesar should have a fresh supply of money, and that his command should be renewed to him for five years more. It seemed very extravagant to all thinking men that those very persons who had received so much money from Caesar should persuade the senate to grant him more, as if he were in want. Though in truth it was not so much upon persuasion as compulsion that, with sorrow and groans for their own acts, they passed the measure. Cato was not present, for they had sent him seasonably out of the way into Cyprus; but Favonius, who was a zealous imitator of Cato, when he found he could do no good by opposing it, broke out of the house, and loudly declaimed against these proceedings to the people, but none gave him any hearing; some slighting him out of respect to Crassus and Pompey, and the greater part to gratify Caesar, on whom depended their hopes.

“After this, Caesar returned again to his forces in Gaul, when he found that country involved in a dangerous war, two strong nations of the Germans having lately passed the Rhine to conquer it; one of them called the Usipes. the other the Tenteritae. Of the war with the people, Caesar himself has given this account in his commentaries, that the barbarians, having sent ambassadors to treat with him, did, during the treaty, set upon him in his march, by which means with eight hundred men they routed five thousand of his horse, who did not suspect their coming; that afterwards they sent other ambassadors to renew the same fraudulent practices, whom he kept in custody, and led on his army against the barbarians, as judging it mere simplicity to keep faith with those who had so faithlessly broken the terms they had agreed to. But Tanusius states that when the senate decreed festivals and sacrifices for this victory, Cato declared it to be his opinion that Caesar ought to be given into the hands of the barbarians, that so the guilt which this breach of faith might otherwise bring upon the state might be expiated by transferring the curse on him, who was the occasion of it. Of those who passed the Rhine, there were four hundred thousand cut off; those few who escaped were sheltered by the Sugambri, a people of Germany. Caesar took hold of this pretence to invade the Germans, being at the same time ambitious of the honour of being the first man that should pass the Rhine with an army. He carried a bridge across it, though it was very wide, and the current at that particular point very full, strong, and violent, bringing down with its waters trunks of trees, and other lumber, which much shook and weakened the foundations of his bridge. But he drove great piles of wood into the bottom of the river above the passage, to catch and stop these as they floated down, and thus fixing his bridle upon the stream, successfully finished his bridge, which no one who saw could believe to be the work but of ten days.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated October 2024